- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Misguided Fusion Research

Robert L Hirsch1 and Roger H Bezdek2*

1Senior Energy Advisor at MISI, USA

2Founder and President of MISI, USA

*Corresponding author: Roger H Bezdek, Founder and President of MISI, Washington D.C., USA

Submission: July 08, 2021Published: July 14, 2021

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume8 Issue4

Opinion

The ultimate source of energy in the universe is nuclear fusion. It powers the sun and the stars. To work, extremely high temperature and high-pressure gases - plasmas -- are required. The stars hold their plasmas by gravity. On earth in an attempt to harness fusion for electric power production, magnetic fields are required to hold fusion plasmas, an extremely difficult task. Decades ago, a Russian magnetic field configuration - the tokamak - appeared promising and countries built ever larger tokamak experiments to develop this “Magnetic Bottle.” The aim was to progress to a system large enough that more energy would be produced than was required to heat the fusion plasma. While substantial progress was made, ever so slowly the promise of commercially viable tokamak fusion power ebbed away. Some recognized the situation, but most simply continued to increase the size of their tokamaks and their budgets [1-4].

Currently, there are several large tokamak experiments worldwide. The largest is ITER under construction in France. ITER’s goal is to create a tokamak plasma that produces ten times more energy than was used to heat the plasma. ITER was originally envisioned to cost roughly $5 billion, a level that might extrapolate to a reasonably priced tokamak fusion power plant.

But reality slowly intervened, and the cost of ITER escalated. ITER managers now contend that ITER’s cost is roughly $22 billion. The U.S Department of Energy, which is supposed to be paying 9% of total ITER costs, has estimated that actual ITER costs are roughly $65 billion. Even at $22 billion, the cost of an ITER-like electric power plant would be roughly ten times the cost of a nuclear fission power plant, a totally unacceptable cost.

But that’s not all. The easiest fusion fuel combination -- not easy -- involves two isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium and tritium. Deuterium occurs in water and is easily extracted. Tritium does not exist in nature and decays radioactively. It must be produced.

It’s now recognized that world supplies of tritium are inadequate for future fusion pilot plants, let alone commercial fusion reactors. In other words, fusion researchers are developing a fusion concept for which there will not be enough fuel! But related research nevertheless continues.

How could this happen? First, the cost escalation happened so slowly that it went almost unnoticed. Fusion researchers have done their own program reviews for over 60 years. In effect “The foxes are guarding the henhouse.” Practical electric power engineers, utility executives, and others who are not members of the fusion mafia have been excluded from fusion program evaluation. We recently urged the Secretary of Energy to appoint an independent panel to conduct the objective, independent evaluation necessary to lay these facts bare. The Secretary gave our request to the leader of the fusion program, who responded that the program is guided by two recent fusion panels. Those panels consisted of fusion physicists and related researchers - most with vested interests in continuing the current program [4-8].

The situation is tragic. With so many people and institutions at risk of losing jobs and funding, the “wagons have been circled,” and programs continue. Talented people and large sums of money are being wasted; the current annual U.S. fusion budget is over $650 million.

And that’s not all. ITER will yield roughly 30,000 tons of radioactive waste. Researchers feel this is not a problem because the waste will radioactively decay in roughly 100 years, which they feel is acceptable. Acceptable?

Is there hope for commercially viable fusion power? Yes, because other “magnetic bottles” and fusion fuel cycles exist. The related physics is much more difficult, but we won’t know if any of these options are workable unless we try. Currently, there’s no government support for these options.

We continue to have hope for viable fusion power. However, without sharp focus, capable management, and independent oversight, it won’t happen. Change will be traumatic and will take political courage. It’s up to Congress and the White House to act.

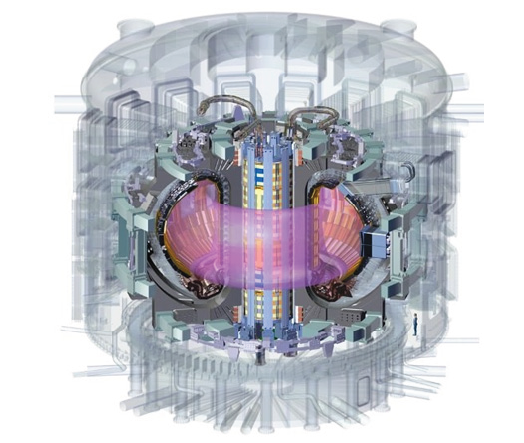

If a graphic is deemed useful, the following might be considered (Figure 1):

Figure 1:

A cutaway pictorial of the core of the ITER tokamak, showing the donut shaped plasma (blue) inside a massive, complicated magnet arrangement. For size, note the person in the lower right side. From ITER.org.

(Note: Permission to use this figure was granted by the ITER organization, as long as we “kindly credit us @iter.org.”

References

- ITER.org

- GAO (2007) Fusion Energy - Definitive Cost Estimates for U.S. Contributions to an International Experimental Reactor and Better Coordinated DOE Research Are Needed.

- Kramer, David (2018) ITER disputes DOE’s cost estimate of fusion project. Physics Today.

- Hirsch RL, Bezdek RH, Public Acceptance of IT-Tokamak Fusion Power. Submitted for publication.

- Abdou M. et al. (2021) Physic and technology considerations for the deuterium-tritium fuel cycle and conditions of tritium fuel self sufficiency. The Nationals Academy Press. Bringing Fusion to the U.S. Grid. 2021, Nuc. Fusion 61:

- Hirsch RL (2021) Fusion Energy Research- A Call for Scrutiny.

- https://science.osti.gov/-/media/fes/fesac/pdf/2020/202012/DRAFT

© 2021 © Roger H Bezdek. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)