- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Urban Resilience: A Critical Study on Kerala Flood-2018

Sameer Ali Ar1* and Abraham George2

1Research Scholar, Department of Architecture and Planning, India

2Associate Professor, Department of Architecture and Planning, India

*Corresponding author: Sameer Ali Ar, Research Scholar, Department of Architecture and Planning, India

Submission: July 14, 2020Published: July 01, 2021

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume8 Issue4

Abstract

Urban Resilience for any city is a gap to be fully understood and assimilated in Urban Planning. Globalization and rapid Urbanization in recent years have led to newer challenges as higher densities, greater demand for infrastructure, resources, environmental and man-made hazards are on the increase. Cities are trying to cope-up with the rising demands through various planning techniques and modern applications and planning models. However, each city’s landscape is different and many a times these approaches might not adhere appropriately to every aspect of a city. One of the worst situations where the reality could be understood; resilience of a city would be truly realized, is when disaster strikes. The flood in Kerala State that happened in August 2018 is one such example where a lot can be studied. Not only the fact of ‘coping up to the maximum damage possible’, it is also ‘how fast human lives can be brought back to their normal stable level’. The level; whether prevailed original condition prior to hazard or higher or acceptable lowest, is another question to be resolved. In most cases the governmental and other agencies would strive is to attain the lowest acceptable level. However, it is most appreciated if the resilience exceeds the original level with new approach to planning, design and infrastructural capabilities so that the disaster, even if it strikes again will affect the damage prevention better. The ability of the city or the extent of resilience shown by Kerala is very strong, especially when compared to similar scale disasters that have struck in India and even other parts of the world. The paper tries to study and evaluate these factors that lead to faster resilience of the state of Kerala in order to model a flexible and more effective urban resilient planning approach.

Keywords:Resilience; Disaster; Flood

Introduction

A simplified version of resilience would be simply ‘being strong’ or ‘bouncing back’ after a fall, or workers’ capacities to manage stress, as per the former chancellor, the bank of England, George Osborne’s, discourses around building a ‘resilient economy’ [1]. Resilience also means ’to hold on to one another’, for greater strength in unity which is seen in the Kerala floods of 2018. Recommendations for increasing Urban Resilience include techniques ‘to multiply weak ties and to form alliances with people of different faiths’ and to mix housing patterns and provide adequate services in poor neighbourhoods [2]. In short, a multi-disciplinary form of Urban Planning or Mixed Residential system is seen appropriate in bringing the resilience level up.

Finding the appropriate predictors of resilience has become an arduous task because of the high-rising willingness to see the behaviours of people as influenced by potent exchanges with the environment and significant others. Cross-legged prospective studies are necessary with advanced statistical methodologies and multivariate data collection strategies capable of analysing transactional data [3]. Urban Resilience has been of paramount importance for cities around the globe especially, mega- cities which exceed 10 million population [4]. Of the 23mega-cities in the world, 16 of them are in coastal zones and within 100km to 50km elevation from the MSL [4]. Research also indicates that there is a critical gap between urban and coastal research, which is to be done. It is often observed that urban resilience lacks proper cognizance by authorities; in the political and economic aspects, thereby bringing ‘social injustice’ and ‘undesirable environmental loading’ [5]. As such, at times of crisis a city is usually not well equipped to handle extreme situations. However, it is only during post disaster events; significance of a resilient city is taken into consideration.

Urban resilience- Indian context

India is a developing country with the highest number of cultural diversities in the world. This would mean eventual transition to a mixed cultural process governing colonial urban development that is unique and discrete specific to each region. This is seen in colonial cities where utmost importance is given to values, behaviour, traditions, and the distribution of social and political power within it [6]. Studies have proven people’s emotional connections to their homeland contribute positively towards environmental concerns [7]. Such is the case of Kerala during its devastating flood in August 2018. The local response was spontaneous and incertitude led to the best form of empirical support that is crucial people’s response in any disaster.

Failure of a society to cope up with a disaster or a disruption simply corresponds to their ‘inability to augment in a sustainable manner to manifest resilience’ [8]. Social attitude plays an explicit role for any society and they are the first responders when a disaster strikes. The influence they can create in increasing resilience, and as such reduce the effect of a disaster and its mitigation, is definitely indispensable. The faster and appropriate the response of ‘People as sensors’, higher is the positive impact on resilience [9]. The tech-savvy segment of the public helps to create local and global awareness, first-hand reports, upload pictures/videos, create blogs helps promulgate information sometimes even faster than government agencies to help seek out family, friends or any needy person. However, the spread of unauthenticated fake information is also a concern as it spreads avoidable panic in an already adverse state.

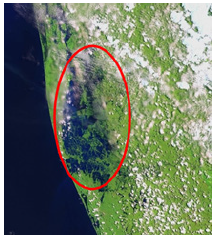

Kerala

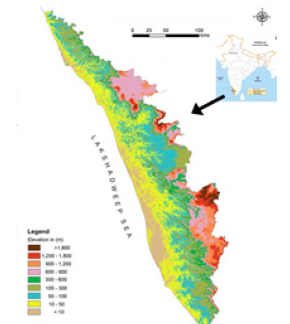

Kerala is a south Indian state with more than 33 million populations, with a geographic area extending to 39,000km2. It has a coast of 590km and the width of the state varies between 11km and 121km. Geographically, Kerala can be divided into three climatically distinct regions: the eastern highlands; rugged and cool mountainous terrain, the central mid-lands; rolling hills, and the western lowlands; coastal plains (Figure 1) [10].

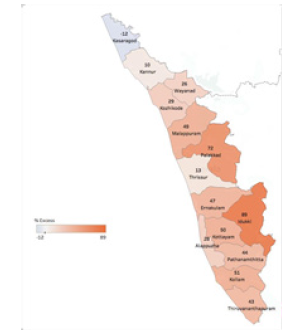

Kerala ranks first among all the other states in terms of Human Development Index (HDI) [11]. Contrary to many other states of India, Kerala ranks very high in many other Human Development Indicators as well at par with those of developed countries. For instance, Kerala ranks first among states in inequality adjusted HDI which simply corresponds to least loss of HDI in terms of inequality [12]. As compared to the National average of 74% literacy rate, Kerala reports a rate of 94% [13]. The higher the HDI, the higher is also the coping capacity but with greater cumulative loss potential, it might pose an even higher risk. About 90% of the rainfall in a year occurs during six monsoon months, from June to November. Kerala State has an average annual precipitation of about 3000mm (Figures 2-9) [14]. The continuous and heavy precipitation that occurs in the steep and undulating terrain finds its way into the main rivers through innumerable streams and water courses. Kerala being a coastal city with a coastline of 590km is however vulnerable to Natural Disasters such as Floods, Tsunamis and even Landslides along the slopes of the Western Ghats. There are 39 hazards categorised as naturally triggered hazards and anthropogenic ally triggered hazards by the Kerala State Disaster Management Plan [15]. Also, Kerala is one of the most densely populated states of India with 860 persons per sq.km making it more susceptible to losses and damages from a disaster [13].

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

Figure 8:

Figure 9:

Kerala floods

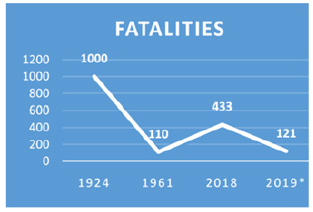

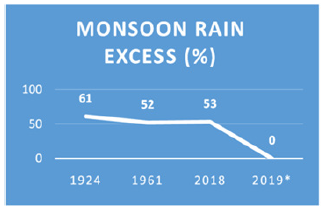

Out of the above-mentioned hazards, floods are the most common of natural hazards in the state. Close to 14.5% area of the State is prone to floods. Riverine flooding is a recurring event consequent to heavy or continuous rainfall exceeding the percolation capacity of soil and flow capacity of streams and rivers. The events that trigger an inundation are mainly rainfall, channel slope, land use in the flood plains, materials of stream banks and relative height of banks [16]. Before the Flood of 2018 and 2019, the previous flood of such devastating scale happened almost a century ago in 1924. More commonly known as the ‘99 floods; since it happened in the Malayalam calendar year of 1099, the then flood had deeply submerged many districts of Kerala from Thrissur to Alappuzha even parts of Idukki. Multiple major landslides were triggered in Karinthiri Malai probably due to toe erosion which irreparably damaged the then Munnar road. The present-day road that leads from Ernakulam to Munnar was constructed after this incident. After 1924; the next major flood was in 1961 in the Kerala Periyar Basin with a 52% increase in Monsoon rains during that time. Casualties were relatively lesser; at 110, this time as compared to the previous event due to lesser urban densities in these areas. The flood seems to be recurring at a closer frequency especially when it’s happening back-to-back years. The year 2019 ran through a deficit of 29% rainfall on 1 August 2019 to no deficit on 14 August 2019 which clearly implies the excess rain received in just 2 short weeks [16]. 40 people have been injured in floodrelated incidents while over 21 people are believed to be missing in the state after heavy flooding. A total of 1,789 houses have been completely damaged due to flooding and over 26,000 people have taken refuge in relief camps [16].

August 2018 Kerala flood

From June to August 2018, Kerala has received one of the heaviest rainfalls, 42% more than the normal average and thus experienced the worst of floods in its history since 1924 [17]. With the heaviest rainfall from 1-20 of August, the State has received 771mm of rainfall [15]. The rains triggered several landslides in different districts and the forced the release of excess water from over 37 dams further reportedly, aggravated the flood situation. From 10 districts, 341 landslides had been reported during this period. The most intense of rains happened on August 15 and 16 with intensity of 235.5mm which has a probability of 0.5% chance for any given year. It only rose to 294.2mm on the third day August 17 which is unparalleled [18]. The devastating floods and landslides affected 5.4million people, displaced 1.4 million people, and took 433 lives out of which 268 were men, 98 women and 67 children [19].

Six of the major reservoirs in the state were already at 90% capacity even before the rains started lashing in August 20191. The untimely release of water from the dams were also said to be a reason that attributed towards the flooding [18]. The water levels in several reservoirs were almost near their Full Reservoir Level (FRL) due to continuous rainfall from 1st of June 2019. Another severe spell of rainfall started from the 14th of August and continued till the 19th of August, resulting in disastrous flooding in 13 out of 14 districts. Over 175 thousand buildings have been damaged either fully or partially, potentially affecting 0.75 million people. More than 1700 schools in the State were converted to relief camps during the floods. The worst affected were the workforce in the informal sector that constitute at least 90% of Kerala’s workforce [20]. It is estimated that nearly 7.45million workers, 2.28million migrants, 34,800 persons working in micro, small and medium enterprises, and 35,000 plantation workers; majority being women, have been displaced. The major issue being these workers are usually dailywagers and they experienced wage losses for 45 days or more Table 1.

Table 1: Month-wise rainfall and percentage departure from normal [14].

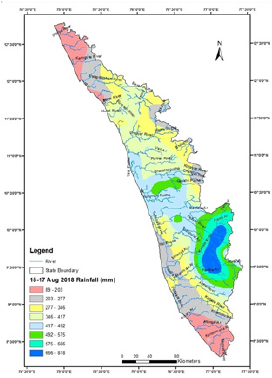

Analysis of 3 days cumulative rainfall of 15-17, August 2018

To analyse the August 2018 flooding phenomenon of Kerala, daily rainfall data from 1 June 2018 to 20 August 2018 has been obtained from the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD). On scrutiny of data it has been found that cumulative rainfall realised during 15-17, August 2018 was significant, with places such as Peermade receiving more than 800mm of rainfall [14]. The storm of 15-17, August 2018 was spread over the entire Kerala with eyecentred at Peermade, a place between Periyar and Pamba subbasins. The storm was so severe that the gates of 35 dams were opened to release the flood runoff. All 5 overflow gates of the Idukki Dam which is the largest arch dam in India were opened, for the first time in 26 years. Heavy rains in Wayanad and Idukki caused severe landslides and left the hilly districts isolated. On August 15, Kochi International Airport; India’s fourth busiest in terms of international traffic and the busiest in the State, suspended all operations until August 26, following flooding of its runway. As per the reports in media, the flooding has affected hundreds of villages, destroyed several roads and thousands of homes have been damaged. The Kerala State Disaster Management Authority placed the State on ‘red alert’ as a result of the intense flooding. A number of water treatment plants were forced to cease pumping water, resulting in poor access to clean and potable water, especially in northern districts of the state. A number of relief camps were opened to save the people from the vagaries of flood. The situation was regularly monitored by the State Government, Central Government, and National Crisis Management Committee which also coordinated the rescue and relief operations [14].

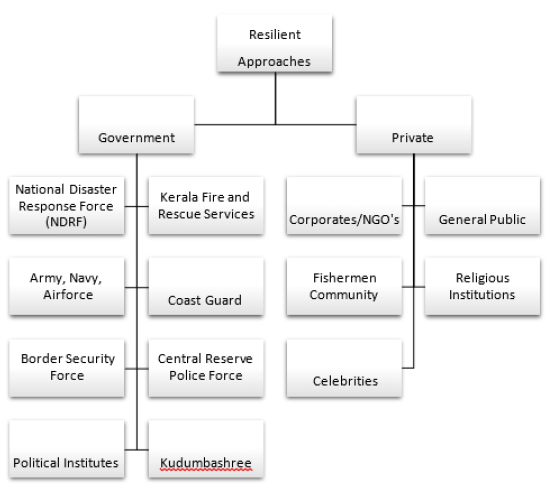

Response and Relief Approaches Adopted in Kerala

Government and Private Organisations were actively involved in the resilient approaches that led to a fast recovery of the State. It can be divided as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Classification of stakeholders involved in response and relief activities.

Government organisations

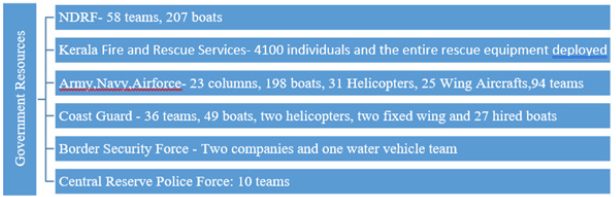

Support from all involved Government agencies was vital for resilience, since Kerala has not experienced a similar scale of disaster in nearly a century, the level of support required was unknown and the only way possible was to provide ‘as much as support’ the Government could provide in every possible manner Table 3.

Table 3:Government resources allocated for Kerala flood 2018 [19].

Kudumbashree

Kudumbashree started as a joint programme between the Government of India and NABARD; National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, focused on the upliftment of the economically weaker section of the community for women exclusively. Kudumbashree is registered under the ‘State Poverty Eradication Mission’ (SPEM); a society registered under the Travancore Kochi Literary, Scientific and Charitable Societies Act 1955. It is one of the largest women-run organisations in the world and has a State Mission Office located at Thiruvananthapuram and 14 District Mission Teams, each located at the district headquarters that is actively involved in local community services across the state [21]. Apart from regular community services, the Kudumbashree was actively involved in the relief and rehabilitation works related to the flood relief operations. Some of the notable areas of involvement include:

A. Support to cleaning more than 0.1 million houses and public offices

B. Counselling support to more than 10,000 families

C. Collection and distribution of relief materials from possible sources

D. Support to Volunteers in various flood relief activities

E. Housing of flood victims in Kudumbashree exclusive houses as temporary shelters

F. Cleaning of public properties

G. Support to local self-government for all activities related to flood relief

H. Support to local level coordination

Political parties

The flood situation was very grieving. Rather than blaming the ruling party for lack of preparedness for the disaster; both the ruling and opposition parties, joined hands in providing relief activities within the State. This helped in boosting quick State and National support to necessitate law and order in support of the relief activities [22]

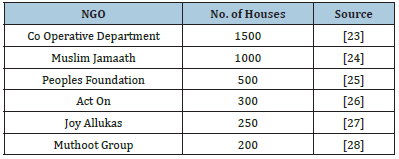

Private organisations

More than the Governmental support, it was the private organisations that were involved as first-hand responders. The swift and timely support received, helped save hundreds of lives and prevented cumulative effects of the disaster Table 4.

Table 4: NGO Housing projects for Kerala flood 2018.

Corporate/NGO’s

NGO’s have been very active in providing services in various parts of need. Some of the Housing projects for the flood victims by the NGO’s are as follows:

Fishermen community

The fishermen community played one of the most important roles in Kerala’s Resilience. Being first- responders they were able to rescue at least 65000 lives [19]. A total of 4537 fishermen had risked their lives on 669 boats with very basic amenities to support the rescued [19]. However, timely intervention helped the stranded reach relief camps and get necessary first-aid and other amenities. The eagerness of the fishermen community needs to be appreciated even when economically they might be in a very critical state. Community bonding is seen from such actions of the society (Figure 10). Being able to navigate through water-borne areas with ease, they were the best help in terms of local support and knowledge of routes and people. Many rescuers claimed the boats of NDRF were too small and rescue was majorly due to fishermen’s boats.

Figure 10: A fisherman helping a lady board rescue boat [59].

General public

Support from common people was crucial for Kerala’s resilience. Some of them being:

Setting up of relief camps: Over 1million people were displaced and stayed in relief camps across 3274 camps in the flood-hit districts [23-29]. Many of these camps were set-up and run by the common public in safer locations such as Schools, Hospitals, Playgrounds, Markets, Stadiums, Religious places of worship without differentiation or places that were free from the flood. Anyone could donate food and other basic amenities. These supports were bought from different places to these relief camps for distribution, especially medicines and first-aid. People were asked to stay in these camps until rehabilitation was complete. From the wholehearted support received, food supply was later abundant in most camps. After providing for the camp-mates, this excess food was then given off to the poor and economically weaker section of the society.

Local non-profit unrelated organisations: Apart from the fishermen community, other local non-profit organisations and social clubs too joined in the relief work activities by providing the resources that were available to them. For example, the Off-Road Riders Club in Idukki volunteered themselves with the help of their off- road vehicles to navigate through rough terrain inaccessible by normal vehicles to engage themselves in the rescue activities [30]. Many of these vehicles are modified not in tune with the traffic regulations of the Country (Figure 11). However, at times of crisis, it was these modifications which helped save those extra lives. This also brings the question of amendments that needs to be made in the laws which are at odds with such requirements.

Figure 11:Modified Off-Road vehicles being used by police for relief work [60].

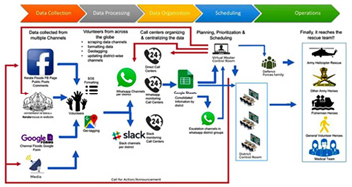

Social media influence: A lot of emergency information’s such as road blocks, disrupted paths, availability of services at relief camps and even request for donations were widely propagated through multiple social- media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter etc [31]. The Government made announcements were also spread by the people through these sources (Figure 12). This helped people in remote areas to inform the authorities, pinpoint their stranded locations [32]. Due to the flood-condition in many areas, accessibility to better grounds for emergency treatments after rescue would sometimes be time consuming. At such times lives may be lost if not adhered immediately. This is when the available resources need to be utilised judiciously. Several Religious Institutes opened up their spaces for people of any community to rest, have food or even request for help that were within their jurisdiction. A mosque in Malappuram offered their Mosque’s prayer hall to be used as an Autopsy room when time were against the odds [33].

Figure 12:Flow chart of data for emergency response [61].

Free services: Due to flood, damage to property was inevitable. Completely and, partially destroyed houses and loss of personal belongings affected the mental condition of any individual. At this time, many people tried to do whatever they can, to support their fellow citizens. Many free service centres for damaged vehicles in floods have been started by both 2-wheeler manufacturing brands and private groups taking support from the local work force. This also helped reduce the high demand on authorised service centres post disaster. Most people were able to get their vehicles running in a matter of days [34].

Celebrity participation: Adding to the local support as firstresponders, the number of people and enthusiasm showcased further encouraged public-participation in relief activities. Even celebrities such as movie actors were actively involved in the relief activities for days giving physical support as well as sharing vital information in the form of photos and video on social media platforms [35]. Public behaviour can be tuned to support a cause with the help of clarifications by known experts or well-known individuals’ states [36] with the help of mass communication. The floods of 2019 also saw the return of these individuals to support the affected again in flood struck regions [37] Table 5.

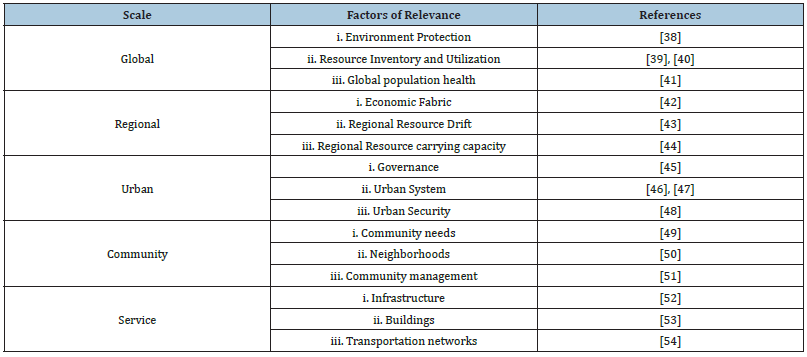

Table 5: Factors of resilience at different stages.

Resilience is found in all stages namely Global, Regional, Urban, Community and Service levels. At each level, the demands, facilities required and level of intervention required are different. All-in-all for a city to be truly resilient, every stage needs to be addressed with utmost priority as they are all dependent factors (Figure 13). Many of the above studies prefer multiple connections between the scales of resilience. The inter- connectivity is yet another area that needs to be explored. Community Resilience is the least cited subject among most studies, but the studies that do suggest them accentuate its impact it makes on resilience [38-51] highlights the influence the fishing community has had on the city’s resilience (Philippines) during times of crisis, so had been the case of Kerala as well during its flood in 2018. Community involvement changed the complete perspective of Urban Resilience in Kerala during and after the event of the flood. Rather than the built forms, it was the human effort that helped achieve Kerala it’s true resilience. Compared to any similar scale of disaster around the globe, Kerala was able to be truly resilient in just a matter of months. ‘The people and the state worked in tandem, a rare sight for an Indian State in crisis’, quoted by [52-55] of the Observer Research Foundation states that the state achieved its previous condition seamlessly and much quicker than usual when compared anywhere else of a similar magnitude [55]. Also points out the fact that managing the disaster efficiently and clinically was comparable to that of most developed nations.

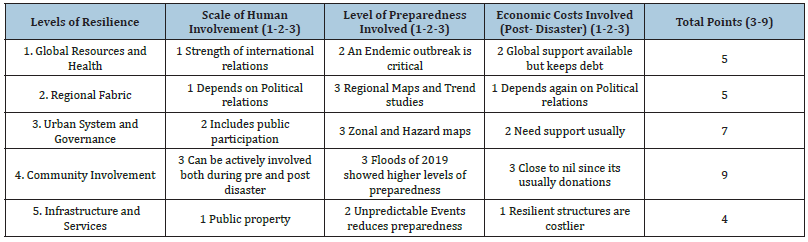

The youth of the state were too actively involved in running relief camps and mobilise resources [56], states how they can serve as templates to the rest of the country on how to unite during times of crises. From the above factors of resilience studies and the relief approaches adopted in Kerala, a chart has been prepared including the factors of involvement, preparedness level and costs involved in order to obtain a 9-point scale with 3 points under each category (higher the number, better the resilience). 1 corresponding to low score, 2 for medium, and 3 for high; 0 score has not been assigned since all are factors of resilience as adopted from above mentioned studies. From Table 6, it is seen that resilience through community involvement is the highest factor of resilience across various factors of involvement. The costs involved are the lowest, external dependencies are the lowest and the time of interaction is the fastest. The situation in Kerala helped achieve a new fabric in Resilience that was previously overlooked. A positive community relationship is necessary however to achieve this state. Cities need to majorly focus on how to bring their communities together for a myriad of factors and community resilience is only one that adds to it.

Levels of Resilience

Figure 13: Breakup of factor weightages contributing to Urban Resilience for calculating index for a given city.

Resilience is found in all stages namely Global, Regional, Urban, Community and Service levels. At each level, the demands, facilities required and level of intervention required are different. All-in-all for a city to be truly resilient, every stage needs to be addressed with utmost priority as they are all dependent factors (Figure 13). Many of the above studies prefer multiple connections between the scales of resilience. The inter- connectivity is yet another area that needs to be explored. Community Resilience is the least cited subject among most studies, but the studies that do suggest them accentuate its impact it makes on resilience [38-51] highlights the influence the fishing community has had on the city’s resilience (Philippines) during times of crisis, so had been the case of Kerala as well during its flood in 2018. Community involvement changed the complete perspective of Urban Resilience in Kerala during and after the event of the flood. Rather than the built forms, it was the human effort that helped achieve Kerala it’s true resilience. Compared to any similar scale of disaster around the globe, Kerala was able to be truly resilient in just a matter of months. ‘The people and the state worked in tandem, a rare sight for an Indian State in crisis’, quoted by [52-55] of the Observer Research Foundation states that the state achieved its previous condition seamlessly and much quicker than usual when compared anywhere else of a similar magnitude [55]. Also points out the fact that managing the disaster efficiently and clinically was comparable to that of most developed nations.

The youth of the state were too actively involved in running relief camps and mobilise resources [56], states how they can serve as templates to the rest of the country on how to unite during times of crises. From the above factors of resilience studies and the relief approaches adopted in Kerala, a chart has been prepared including the factors of involvement, preparedness level and costs involved in order to obtain a 9-point scale with 3 points under each category (higher the number, better the resilience). 1 corresponding to low score, 2 for medium, and 3 for high; 0 score has not been assigned since all are factors of resilience as adopted from above mentioned studies. From Table 6, it is seen that resilience through community involvement is the highest factor of resilience across various factors of involvement. The costs involved are the lowest, external dependencies are the lowest and the time of interaction is the fastest. The situation in Kerala helped achieve a new fabric in Resilience that was previously overlooked. A positive community relationship is necessary however to achieve this state. Cities need to majorly focus on how to bring their communities together for a myriad of factors and community resilience is only one that adds to it.

Table 6:Weights assigned to different levels of resilience.

Discussion

The state of Kerala was able to manage the flood disaster efficiently despite the lack of preparedness with Community participation being the key factor especially in its case. The overwhelming support from different groups of people and organisation helped reach Kerala to its stable state within a few months post disaster. Some of the takeaways and recommendations to increase Resilience are:

A. Encourage the ethnic and economic integration of different neighbourhoods.

B. Mix housing patterns and create common public spaces for increased interaction.

C. Blend different houses of worship of all faiths from the grassroots of city planning.

D. Plan for the pandemic by providing for adequate municipal and private services, even in the event of the disaster of large proportions.

E. Be prepared with stock of extra amenities available at all times, especially potable water.

F. Create special cells for constant monitoring and also vigilant quick-response teams dedicated to different areas. Create a Zonal Rebuilding map and integrate with special cells.

G. Ensure basic services especially for the poor neighbourhoods, since they are the keystone for the population of any metropolitan region, that is, establish standards for housing unit loss per unit population per year.

H. Ensure buildings reconstructed are using disaster resilient techniques and away from flood plains and slopes.

I. Create public awareness and prepare people to respond in time of crisis; both in affected and unaffected areas.

J. Restoration of Irrigation-cum-Drainage systems.

K. Prepare an update Hazard Vulnerability map for Kerala and also establish methods of evacuation or resistance at times of Risk.

L. Establish Resilience Efficiency Index to establish level of preparedness and assistance.

Any disaster is an opportunity to establish a robust human rights-based approach at all phases of recovery cycle, based on the principles of non-discrimination, participation, and ‘leaving no one behind’ as per Agenda 2030 [19]. On an alternate dimension, frequent occurrences of disasters in the same place have also raised the eye-brows of sceptics claiming this to a result of conspiracy theory. Occurrences of flash floods and unpredictable weather conditions further heighten this sceptical thinking. The chances for a cloud-seeding event due to disputes with neighbouring states/ countries cannot be out-ruled either [57-63].

Conclusion

Public participation and its encouragement is the key factor contributing to a city’s resilience. Feelings of oneness, keeping aside personal outlooks such as political, religious or caste-based classification are factors the government should focus to implement at times of crisis for a faster resilience. The potential for Green Infrastructure is another aspect that is gaining rapid attention which has the potential to reduce damages from natural disaster especially after the catastrophic events. Preservation of natural eco-system and flood plains and integrating them into the urban fabric will increase community resilience while providing social, economic and environmental benefits. The factors of resilience decoded from the studies of Kerala further clarifies the importance of community involvement that needs to be made a standard for resilience planning for any region or city. The outcome will be a healthier community with higher resilience to future events of disasters. Further, establish Resilience Efficiency Index to establish level of preparedness and assistance even to budgeting and fund allocation at governmental level.

References

- Kim Trogal IBRLDP (2018) Architecture and Resilience: interdisciplinary dialogues, Routledge New York, USA.

- Deborah Wallace RW (2008) Urban Systems during Disasters: Factors for Resilience. JSTOR.

- Kumpfer KL (2002) The Resilince framework in the resilince framework, pp. 179-224.

- Mark Pelling SB (2013) Megacities and the coast-risk, resilience and transformation, Routledge, London.

- Christophe Béné LMGMTCJGTT (2017) Resilience as a policy narrative: potentials and limits in the context of urban planning. Climate and Development, pp. 116-133.

- King AD (1976) Colonial urban development-culture, social power and environment, Routledge, London.

- Megha Budruk HTTT (2009) Urban Green Spaces: A study of place attachment and environmental attitudes in India. Society & Natural Resources, pp. 824-839.

- Oliver Smith A (1996) Anthropological research on hazards and disasters. Annual Review of Anthropology, pp. 303-328.

- Melinda Laituri KK (2008) Online disaster response community: People as sensors of high magnitude disasters using internet GIS. Sensors, pp. 3037-3055.

- Chattopadhyay S, Franke RW (2006) Striving for Sustainability: Environmental stress and democratic initiatives in Kerala in striving for Sustainability, Concept Publishing Company, New Delhi, India, pp. 110-112.

- Radbound U (2019) Subnational Human Development Index.

- Suryanarayana AAKSPMH (2011) Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index for India's States. UNDP India, New Delhi, India.

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner Census of India (2011) Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi, India.

- Commission CW (2018) Kerala Floods of August. Government of India, New Delhi, India.

- Kerala State Disaster Management (2018) "PDNA- Post Disaster Needs Assessment" Kerala State Government, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India.

- India Meteorological Department (2019)

- United Nations Development Programme (2018) Kerala post disaster needs assessment-floods and landslides- August, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

- Prasad R (2018) A rare confluence of events led to flooding in Kerala. IIT Gandhinagar, Gandhinagar, India.

- World Bank (2018) Post Disaster Needs Assessment,United Nations, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

- Mission S (2018) Suchitwa mission damage assessment report, Government of India, New Delhi, India.

- GOK State Poverty Eradication Mission, Organisational Structure (2019)

- The Hindu- Business Line (2018) Kerala political parties unite in call for ‘National Calamity.

- Sumeesh (2018) Relief for Kerala Flood Victims (in Local Language)

- Hindu T (2018) Jamaath plans 1,000 houses for flood victims.

- People's Foundation (2018) Flood Relief Rehabilitation Project distribution.

- Information and Public Relations Department (2018)

- TOI (2018) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/joyalukkas-group-extends-support-to-rebuild-kerala/articleshow/65852909.cms

- News Time Network (2018) News Time Networw.

- The Times of India (2018) Kerala floods: Over 1 million in relief camps, focus on reha.

- The Times of India (2018) Off-road riders turned saviours in flooded Idukki.

- The Caravan (2018) How social media was vital to rescue efforts during the Kerala floods.

- Aswathi Suresh Babu DBSHD (2018) Impact of social media in dissemination of information during a disaster- a case study on kerala floods. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering, pp. 283-286.

- India Today (2019) Kerala floods: Mosque offers prayer hall to be used as mortuary.

- The Times of India City (2018) Kerala: Flood-hit bikers get a helping hand.

- The Better India (2018) Kerala Floods: Malayalam actor sets example, opens house to victims who need shelter!

- Lorien C Abroms EWM (2008) The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior. Annual Reviews 29: 219-234.

- Onmanorama Staff (2019) Tovino Thomas wins hearts as he visits relief camps.

- Woolhouse MEJRAKP (2015) Lessons from Ebola: Improving infectious disease surveillance to inform outbreak management. Science Translational Medicine 7(307): 307rv5.

- Leichenko R (2011) Climate change and urban resilience in Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Elsevier, London, pp. 164-168.

- Campanella T (2006) urban resilience and the recovery of new orleans. Journal of the American Planning Association 72(2): 141-146.

- Asprone DMG, Gaetano Manfredi (2015) Linking disaster resilience and urban sustainability: A glocal approach for future cities. Disasters 39 (Suppl 1): S96-S111.

- Barata Salgueiro TEF (2014) Retail planning and urban resilience - An introduction to the special issue. Cities 36: 107-111.

- Toubin MLRDYSD (2015) Improving the conditions for urban resilience through collaborative learning of Parisian urban services. Journal of Urban Planning and Development 141(4):

- Davoudi S (2009) Scalar tensions in the governance of waste: The resilience of state spatial Keynesianism. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 52(2): 137-156.

- Wagenaar HWC, Cathy W (2015) Enacting resilience: A performative account of governing for urban resilience. Urban Studies 52(7): 1265-1284.

- Barthel SPJEH, John Parker, Henrik Ernstson (2015) Food and green space in cities: A resilience lens on gardens and urban environmental movements. Urban Studies 52(7): 1321-1338.

- Aerts CJH Aerts, Wouter Botzen WJ, Kerry Emanuel, Ning Lin, Hans de Moel, et al. (2014) Evaluating flood resilience strategies for coastal megacities. Science 344(6183): 473-475.

- Server OB (1996) Corruption: A major problem for urban management: Some evidence from Indonesia. Habitat International 20(1): pp. 23-41.

- Mehmood A (2016) Of resilient places: Planning for urban resilience. European Planning Studies, pp. 407-419.

- Chelleri LSTSL (2015) Integrating resilience with urban sustainability in neglected neighborhoods: challenges and opportunities of transitioning to decentralized water management in Mexico City. Habitat International 48: 122-130.

- Pauwelussen A (2016) Community as network: Exploring a relational approach to social resilience in coastal Indonesia. Maritime Studies 15(2):

- Stephanie E Chang, Timothy McDaniels, Jana Fox, Rajan Dhariwal, Holly Longstaff (2014) Toward disaster resilient cities: Characterizing resilience of infrastructure systems with expert judgments. Risk Analysis 34(3): 416-434.

- Takewaki IFKYKTH (2011) Smart passive damper control for greater building earthquake resilience in sustainable cities. Sustainable Cities and Society 1(1): 3-15.

- Testa ACFMNAA (2015) Resilience of coastal transportation networks faced with extreme climatic events. Transportation Research Record, pp. 29-36.

- Sen S (2018) Improved disaster management saves Kerala, despite lack of preparedness.

- Kochukudy A (2018) Anatomy of a flood: How Kerala withstood a calamity.

- Bobins Abraham (2018) From Lord Ayyappa to beef and dogs, here's everything that's been blamed for Kerala Floods.

- Anand G (2019) Nipah scaremongering: Kerala police book two conspiracy theorists.

- ABP Live (2018) Kerala floods: Meet the unsung heroes of rescue mission in rain-ravaged state.

- The Financial Express (2019) SUV owners who rescued people in Kerela floods upset with ban on modified cars.

- Compassionate Keralam (2018) Kerala relief work flowchart.

- Bhuvan (2019) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Generated from Cartosat-1 Satellite data for India.

- NASA (2018) Kerala India Flood.

© 2021 © Sameer Ali Ar. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)