- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Research Method in Sustainability for Higher-Degree Education

Lunevich L*

RMIT University, College of Science, Health and Engineering, Australia

*Corresponding author: Lunevich L, RMIT University, College of Science, Health and Engineering, Melbourne, Australia

Submission: May 18, 2020Published: March 24, 2021

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume8 Issue2

Abstract

This work offers a new conceptual framework for sustainability research for higher degree education (master and PhD), and discusses emerging transdisciplinary research in order to address real problems of sustainability. It is anticipated that the new framework will assist researchers to design, develop and conduct research. It takes the perspective of providing formative advice for people new to transdisciplinary research in sustainability. It presents a summary of tips and techniques to guide researchers’ decisionmaking. It also intended to serve as a guide for practitioners and novice researchers in applying and integrating the research design typology layers into a scholarly manuscript.

Keywords: Sustainability; New framework; Transdisciplinary research; Multi-criteria analysis; Pressurestate- indicators analytical framework; Higher degree education

Why Undertake Research into Sustainability?

Research into sustainability is an intellectual inquiry rooted in and shaped by research

and cultural traditions through multiple ways of viewing the educational world we operate

in. Research into sustainability is transdisciplinary and has recently been described as the

edge of marginalization [1-4]. It is expected in transdisciplinary sustainability research that

a researcher uses a broad range of methods for knowledge integration and production. No

specific set of tools is required to process phases or integrate different types of knowledge

[2,5]. To address the real problem of sustainable living, a new conceptual framework is

necessary, which is discussed in this article.

Zsolnai [4] stressed that progressive businesses that seek to serve society, nature, and

future generations, while maintaining their productivity and efficiency should be concerned

with the sustainability of their business, and the ecosystem of their industry and its business

model. The business model is how a company creates (and destroys) values in the broad

socio-ecological context. The whole-picture view of the mechanism of value creation and

destruction is crucial to studying the role enterprises play in society and nature at large

[4,6]. Sustainability, or sustainability science, is relatively new, having developed the last 10

years as part of the sustainable human progress paradigm [7,8], and has high potential for

development [1,9]. It draws on theory and practice from environmental science, ecological

economics, and social science [2,6], which overlap to some extent, requiring the integration of

tangible and intangible criteria, and a transdisciplinary research approach [10].

Sustainability research in a globalizing world requires understanding the various

disciplines-i.e., environmental science, economics, social science, marketing, society [11-

13]. The development of understanding requires researchers to navigate, filter, and evaluate

different levels of information from the various disciplines [11,14]. In order to create value

(bring solutions to real problems), researchers must assess the level of information required

[1]. A traditional barrier in sustainability research is the ability to integrate tangible and

intangible data-sustainability criteria. Tangible data is frequently available from the economic

field and outcomes are relatively easy to measure and predict by analyzing significant

data volumes. Other data relevant to social and cumulative environmental impact are less

assessable, and sometimes difficult to consolidate into measurable criteria because of

researchers’ value judgements and limitation in data analysis techniques [15,16]. The aim

of this study is to suggest ways in which data can be gathered from the field. Qualitative,

quantitative and mixed approaches are considered.

Understanding the Sustainability Concept

Sustainability in business, society, the economy, and environmental management practice are becoming the forefront issue for researchers, practitioners, and companies worldwide. Sustainability is difficult to study because the concept involves relevance to time, space, and location [11,14]. Moreover, it relates to uncertain positive and negative consensuses of sets of events or actions. Sustainability research delves into layers of cultural and spiritual knowledge, which are frequently difficult to define or uncover [4,17]. In emphasising the important relationship between biophysical, spiritual and socio-cultural systems, discriminating between what is more and what is less certain about the future, and emphasising the need for caution in uncertainty, our interpretations mirror closely those of sharp objects [18]. Sustainability research is often focused on potential improvements in business practices, long-term sustainability-prosperity without compromising future generations [4,17]. Some of the key, current definitions of sustainability expressed in recent publications [4,17] are:

a) Sustainability is a revolution in thinking. b) Sustainability fixes a decline in public morality. c) Sustainability is an effective economic investment, the invisible hand of the market. d) Sustainability is the new capitalism, which is more sustainable, and more just.

Sustainability includes relationships between thinking and reality. Since knowledge of reality is inaccessible to some, critical thinking is the best approach to learning about it. Sustainability is a multi-dimensional concept, and its attributes include systems behaviour, time, space, uncertainty, and cumulative impacts [4,7,17]. A number of principles and methods have been developed to help decision-makers determine the extent to which progress towards sustainability is being achieved [8]. An assessment of sustainability should include:

a) Systemically providing a sense of the total system, not just

the parts.

b) Goal-directed assessment on improving the condition of

people and organisations, meeting needs and having choices.

c) Hierarchical grouping of indicators into sets and arranging

them from the particular and local to the more general and

universal (climate change). A hierarchy allows indicators to

be aggregated, enabling determination of whether the overall

system is improving.

Sustainability is linked with wisdom, frugality, and having a longterm

vision. For instance, interest rates do not just reflect the market

price of capital but are variables with important implications for

social welfare and the sustainability of the economy [4,17]. stresses

that, if it is necessary to reshape economic, political, and religious

institutions, there is also a need for something that can restore the

sense of shared meaning, responsibility, and purpose. Spirituality

should, therefore, be promoted as a public good and virtue [4,17- 33]. This approach should be linked to the practice of spiritually

based leadership and a deep sense of social responsibility [10].

Sustainability can be interpreted as meaning non-declining

natural wealth. Environmental ethics-developed by Jonas (1984),

Fox (1990), Singer (1995) [9], Leopold (1949), and Lovelock

(2000), all cited in [31], and others-offer well-established

operating principles that businesses can follow to move towards

sustainability, including:

a) Promoting natural living conditions and a pain-free

existence for animals and other sentient beings.

b) Using natural ecosystems in such a way that ecosystem

health is not damaged.

c) Not contributing to violation of the earth’s systemic

patterns and global operating mechanisms [31].

d) Business affects the natural environment at different

levels of natural organization:

e) Individual organisms are affected by business through

hunting, fishing, agriculture, animal-based experimentation,

etc.

f) Natural ecosystems are affected by business through

mining, river regulation, building, and the pollution of air, water,

and land, etc.

g) The earth as a whole is affected by business through the

extermination of species, the impacts of climate change, etc.

[31]. Climate change is very largely a natural phenomenon

that has been under way on the earth for several thousands

of millions of years. (At least 2,300 million and, as much as

4,200 million years.) It can be seen recorded very clearly in the

geological record, sometimes in such detail that it is possible to

work out what was happening on an annual, and occasionally

almost seasonal, basis.

The materialistic management paradigm is based on the

belief that the sole motivation behind doing business is moneymaking,

and success should be measured only in terms of the

profit generated [7,19]. However, new values are emerging in

modern business that contribute to a post-materialistic paradigm:

frugality, deep ecology, trust, reciprocity, responsibility for future

generations, and authenticity. Within this framework, making

profits and creating growth are no longer the ultimate aims, but

elements of a wider set of values [20]. In a similar way, cost-benefit

calculations are no longer considered the essence of management

but rather part of a broader concept of wisdom in leadership [21].

Spirit-driven businesses employ their intrinsic motivation to serve

the common good and use holistic evaluation schemes to measure

their success [31].

Individuals, human society, the market, and the globalised

world in which people increasingly find us are changing rapidly

[2,22]. However, many things remain the same [1]. Differentiating

between these and what is changing will enable researchers to

design the correct research methodology and evaluate and filter various levels of data from various fields of knowledge, in particular,

economic, social, and environmental. A research focus could

incorporate some of the issues outlined-e.g., how staff create and

experience sustainability in day-to-day business, what this means

for organisational culture, and how individuals experience it [3].

Transdisciplinary Research is Multi-Dimensional and Multi-Purpose

Transdisciplinary research comprises research efforts

conducted jointly by investigators from different disciplines

to create conceptual and theoretical innovations that enable

investigation and movement beyond a discipline-specific approach

to address a common problem [2]. It dissolves the boundaries

between conventional disciplines and organizes teaching and

learning around the construction of meaning in the context of

real-world problems [2,10]. The research needs to be designed to

the pre-conceived answer. For example, if the aim is to predict the

impact of economic figures on sustainability, meaningful economic

data and trends should be selected, starting with a single measure.

Honan et al. [20] and Hunt [23]. However, society-level, social value

data are often inferred from the community, which is embedded

within a specific culture. For researchers new to the field, there is

a potential danger from observing the behaviors of individuals and

communities who comply with society’s laws and may appear to

have adopted its values [14,24]. The level of research conducted

must be commensurate with the sampling frame in order to produce

comparable results [25,26]. Data gathered from various fields need

to be evaluated before being integrated into sustainability criteria

and linked to the project objectives.

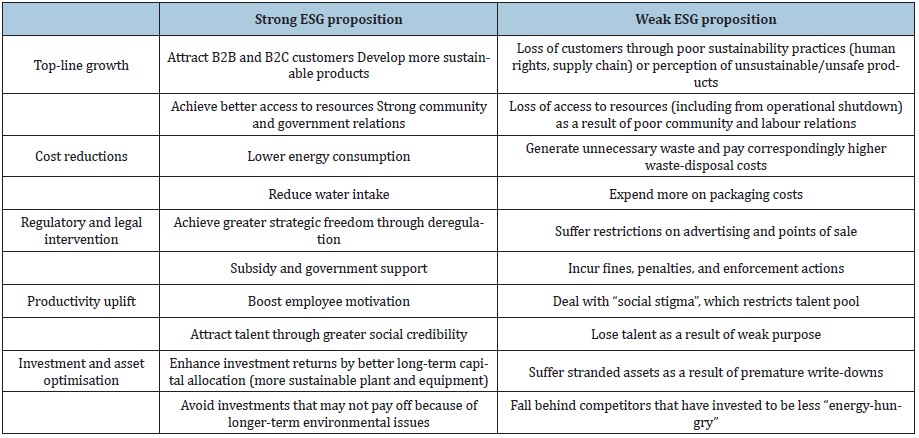

On 19 August 2019, the US Business Roundtable released a

statement affirming businesses’ commitment to more sustainable

business practices and value creation in five essential ways (Table

1) -A broad range of stakeholders, including customers, employees,

suppliers, and communities [27]. A strong Environmental, Social,

And Governance (ESG) proposition links to value creation. The

thinking above leads to questioning the focus of the research. The

research problem and context must be defined carefully, as the way

in which they are framed can both interfere and be influenced by

the research paradigm [10].

Table 1:Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Proposition Links to Value Creation (adapted from McKenzie as cited in Henisz et al. (2020)).

It is important to consider the research context [26]. Thinking about the research will be influenced strongly by the prevailing culture of the local society and understanding of research objectives and practicality is based largely on western concepts of social structure and ethical purpose [26,27]. In order to understand the research problem more fully, researchers must review the existing research-based knowledge, and the theoretical and conceptual areas relating to the area chosen [23]. As the research focus becomes clear and questions are framed, two important issues need addressing: ensuring that the investigation is reliable and valid, and identifying the ethical issues presented [28]. The recommendations of the US National Research Council of [28], which that good research:

a) poses important questions that are possible to answer;

b) relates to available theory and tests it;

c) uses methods allowing direct investigation of the

questions;

d) creates a coherent, explicit chain of reasoning leading

from finding to conclusion;

e) is replicable and fits easily into synthesis; and

f) is disclosed to critique.

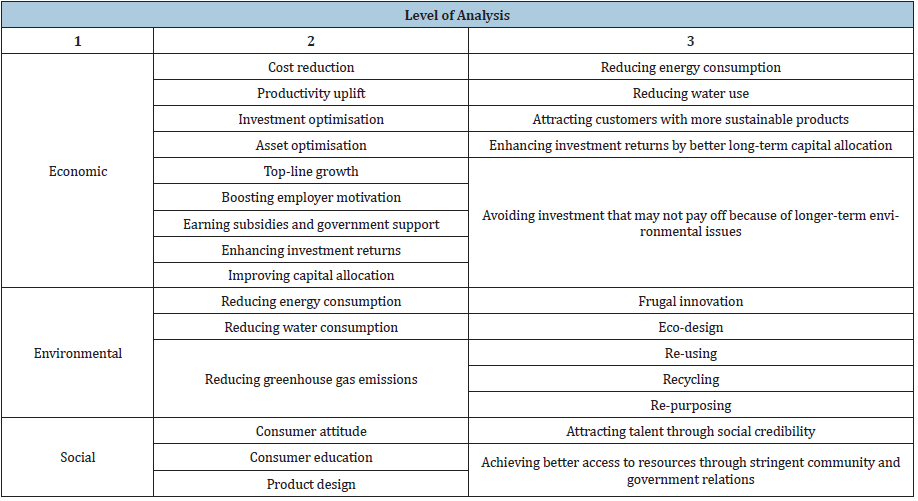

A good place to start transdisciplinary research in sustainability is to use environmental planning techniques, which can assist in developing commonality of understanding of the problem between industry and academia, and community and government. Some techniques include multi-criteria analysis, pressure-state-indicators, analytical frameworks, forecasting, and goal achievement matrices. All of these are useful in sustainability research for mapping the conceptual framework: what is known and unknown, and what is more or less important. There are many problems associated with transdisciplinary research, ranging from the most evident, that different measures are applied to economies and the environment, to the underlying politics of selecting specific criteria to foster a specific research agenda. Table 2 gives an example of three levels of analysis using multi-criteria analysis.

Table 2:Multi-Criteria Analysis.

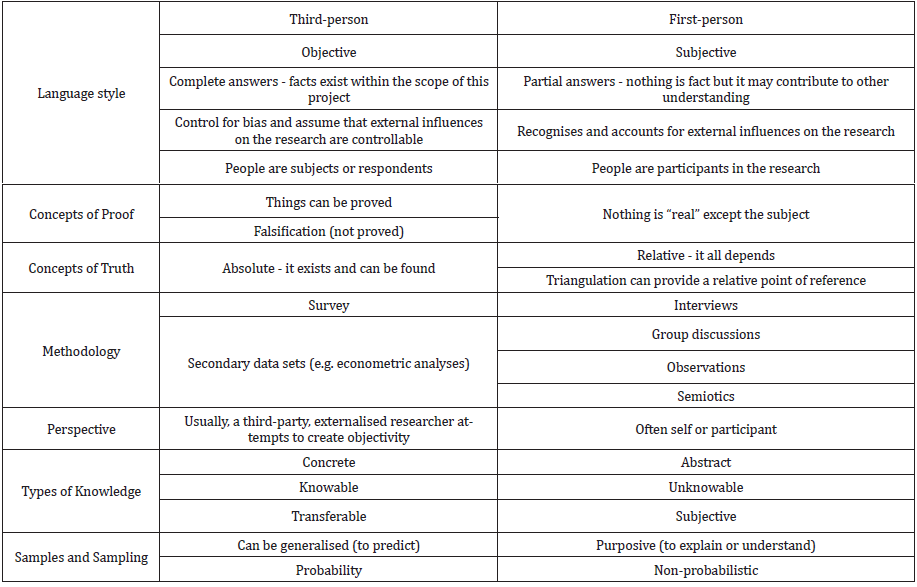

Economic - What economic data need to be selected for the research be credible? What level of data is required for it to be consolidated with environmental and social data? Economic data are measurable and can be verified through various reliable sources. Social - What kind of social data need to be selected or studied for the research to be credible and lead to meaningful conclusions? Environmental - When considering sustainability, reliable environmental data could become unreliable in the longerterm or when it is integrated into the sustainability matrix. This research map- (Table 2) -will lead to important research questions. It will, however, assist in allocating the available theory and testing it. The research methodology is suggested in Table 3.

Discovery Analysis Leads to Research Questions

Kenneth [1] & Brandt [10] point out that research is a seemingly linear process, from initial consideration of the problem and purpose to the approach and design, through to data collection and analysis in practice. The thought processes, choices and actions are all interdependent, and the researcher may move back and forth, considering analysis alongside research design and ethical issues, together with research and outcomes [10]. Moreover, while what it was wished to discover might have been set out, the most important findings may have been neither sought.

Valuing Research Outcomes: Philosophy and Cultural Traditions

Another issue for sustainability research data and design is

philosophical approaches to research conduct. Some cultures rely

heavily on “hard” quantitative research methods and place less

value on either “soft” methods or a combination. In sustainability

research, attention should be given to “soft” qualitative research

methods, for instance survey Brennan [4] notes that a qualitative

research study may not have the same level of acceptance as one

that is quantitative in some societies, and research practices focus

on more quantitative research methods. This issue is associated

with the concept of paradigms-ways of viewing the world-and,

therefore, research practices [18]. Research can be founded on

many paradigms, the majority of which can be categorised into

three domains: positivistic (positivism and post-positivism);

interpretivist (criticism and constructivism); and action/

participatory. There is no need here for extensive debate about the

rights and wrongs of various approaches and methods, the point is that cultural traditions lead to such viewpoints and that alternative

perspectives may be needed in relation to research. If truth exists

and can be found (positivism), the researcher may need to consider

the findings from other perspectives that may have been used in

divining the truth (constructivism). “Your” truth and “my” truth are

not “our” truth (interpretivism). In transdisciplinary research, it

pays to check assumptions at the outset. For all research, this is a

key issue that researchers need to understand and examine for its

impact on the outcomes [2,29].

Epistemology is the study of knowledge-i.e., what is known and

how it can be known. Each culture has its own research traditions

and has developed ways that research is expected to be conducted

over time [22]. For example, in Hong Kong, the “traditional” concept

in epistemology is associated with certainty and expert knowledge

and is overtly put into opposition with constructivism [25].

Epistemology informs research in three main ways:

a) Beliefs about the nature of knowledge, how it can be

structured and the forms that it can take. For example, extensive

“qualitative” field notes have no value if nobody accepts them as

a form of knowledge.

b) Beliefs related to the nature of knowledge, including how

to evaluate and judge criteria for its construction. For example,

if only established experts or elders have the social authority

to “own” and disseminate knowledge, research will be very

difficult for emerging researchers, because authority should

not be challenged. This is particularly relevant in relation to

Confucian heritage – e.g., in China, Korea, and/or Japan.

c) Beliefs about knowledge within the cultural context, and

how it might be viewed (lens or paradigm) and conveyed to

others (communication). For example, can a person deeply

embedded in the culture actually understand it from an

external point of view? Can a person who has never previously

experienced a culture understand it fully? Can culture be

conveyed to others at all? [31].

These issues and differences lead to two questions:

a) how can sustainability be understood if most knowledge

is collected from beliefs (in particular, social aspects) and

constructed social reality instead of eco-reality?

b) will sustainability reflect anything except the socially

constructed reality (illusion)?

To be aware of the source’s epistemological stance, it is necessary to be open to alternative viewpoints throughout the research, from conceptualisation to analysing the data and writing the results. Bias is not “bad” unless it is unrecognised and cannot be accounted for in the research. Some form of bias is always evident in all forms of research. Epistemology and ontology are inputs to axiological positions-i.e., the philosophical foundations against which any research is valued. An emerging researcher should be aware of the potential for differences to be evidenced throughout the research process and to consider different viewpoints. Table 4 is a summary of the impacts of the paradigm and philosophical approaches on sustainability research.

Ethical Dilemmas and Multi-Disciplinary Sustainability Research

Sustainability research can be very complex- (Tables 1-4). Cultural differences and similarities can be found within and between each and all of these. The philosophical foundations of research are not universal, and different cultures have different research traditions, which influence how people see and value it. There are many paradigms at play in sustainability, and those described here are only the start. Those wishing to examine the underpinning philosophies affecting research projects can find a rich source of information in the philosophy of science literature.

Table 3:Research Methodology.

Table 4:Summary of the Impact of Paradigm and Philological Approach on Sustainability Research.

Note. Adopted from Brennan et al. (2011).

The ethics of sustainability research is an emerging field,

as globalisation increasingly dissolves social and geographic

boundaries [20]. Researchers need to be aware of the potential

for cultural imperialism and ensure that their work allows for

autonomy and respect for persons. Informed consent must be

obtained, based on understanding by the participants involved

[1]. Researchers must also recognise the types of information

considered sensitive in the target culture, as well as the possibility

that the knowledge they seek belongs to a community that does not

want to share it with others.

Members of indigenous communities are sometimes reluctant

to provide information to strangers or outsiders [1]. This can

arise from family and filial ties, and/or societal or group rights to

knowledge. Some communities have rules about who can be told

specific types of knowledge. For example, in Australian indigenous

communities, elders pass specific knowledge on to initiates only;

other knowledge can be shared only with women or men, and nonmembers

cannot be told at all [18,30]. An outsider might ask an

offensive question, not knowing that they are not entitled to the

knowledge, so an answer will be given but will not be the “truth”.

In such circumstances, the right to knowledge is not held by an

individual and no individual is entitled to share the community’s

knowledge with others unless the entire community agrees. This

can make gaining informed consent problematic [1]. When some

knowledge must be hidden from others, finding the “truth” can be

challenging. There are likely to be many truths in such contexts:

those that an outsider is entitled to know and those that only the

community is entitled to. While researchers can assume that no

one intends to exploit others, they must work with the community

to ensure that they are represented appropriately in knowledge

dissemination [31].

Alexander [1] & Kenneth [10] both note that culture is often

conceptualised as an iceberg and that many cultural artefacts are

invisible, therefore, to someone not primed to see them. Ensuring

that meaning is found and conveyed to others will require

consideration of the signs and symbols (semiotics) embedded in the

culture. A shared frame of reference should, thus, be established at

the start. Academic research is usually conducted worldwide within

an ethical decision-making framework using principles that can be

traced back 5,000 years [18,32]. This is the key to sustainability

research. Ethical decision-making has distinct cultural traditions

but differs depending on the specific traditions. The main ethical

traditions include Hinduism, Buddhism, Classical Chinese, Judaism,

Christianity, and Mohammedanism (Singer, 1993). This study is not

intended to contribute to the debate surrounding theories of ethics

and their application to research [9]. Nevertheless, it is important

to elucidate some of the ethical principles applied to academic

research with humans and the social science aspects. APA [28] have

developed a widely used set of principles, including, in paraphrase:

a) Beneficence and non-maleficence-every effort should be

made to do no harm during the research and to ensure that it

benefits the participant(s).

b) Fidelity and responsibility-other researchers should not

be allowed to behave in a way that can harm participants.

c) Integrity-researchers should be accurate, honest, and

truthful.

d) Justice-all persons involved should benefit from the

research where possible, and researchers should work within

their competencies and biases.

e) Respect for persons and their dignity-participants’ rights

to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination (autonomy

and informed consent) should be respected, with safeguards

established to protect the vulnerable.

f) Conflicts between ethics and law, regulations, or other

governing legal authority – a if ethical responsibilities conflict

with the law and/or regulations, or another governing legal authority, the nature of the conflict must be clarified,

commitment to the Ethics Code disclosed, and reasonable steps

taken to resolve the conflict consistent with the code’s General

Principles and Ethical Standards. This standard can never be

used to justify or defend violating human rights.

g) Informed consent-those involved in the research must

recognise the research outcomes and intentions.

The full version can be found of the APA principles at http:// www.apa.org/ethics/code. They can be applied to sustainability research, but special care must be taken in some circumstances. The first is that some western notions of ethical research may comprise cultural imperialism [20]. For example, the APA definition of respect for persons includes a right to privacy and confidentiality. Privacy is not a proclaimed human right throughout the world and this principle may seem imperialistic in some countries [28].

Concluding Remarks

Putting a good piece of research together is not easy. Sustainability research always involves multiple options, and alternative scenarios and sub-scenarios, and strategic choices must be made. Every choice brings a set of assumptions about the environmental, social, and economic aspects investigated. There can be no right or wrong direction. It is absolutely critical, however, that the choices made are reasonable and explicit [33].

References

- Alexander ER (2002) The public interest in planning from legitimation to substantive plan evaluation. Planning Theory 1(3): 226-249.

- American Psychological Association [APA] (2020) Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct.

- Brandt P, Ernst A (2013) A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecological Economics 92: 1-15.

- Brennan L, Camm J (2007) Pressure to innovate: Does validity suffer? Australasian Journal of Market Research 15(1): 29-41.

- Brennan L, Voros J, Brady E (2011) Paradigm at play and implications for validity in social marketing research. Journal of Social Marketing 1(3): 100-119.

- Brown D (1991) Human universals. Temple University Press, USA.

- Chan K (2008) Epistemological beliefs, learning, and teaching: The Hong Kong culture context. In: Khine M (Ed.), Knowing, knowledge and beliefs: Epistemological studies across diverse cultures. Springer, London.

- Denscombe M (2007) Good research guide. McGraw-Hill Education, New York, USA

- Groves R, Fowler J, Couper M, Lepkowski J, Singer E, et al. (2013) Survey methodology. Wiley, NY, USA

- Hahn J (2015) Establishing rationale and significance of research. In: Kenneth (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of research design in business and management, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 103-109.

- Hall E (1977) Beyond culture. Random House Digital, Inc. New York, USA.

- Harkness J (1999) In pursuit of quality: Issues for cross-national survey research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2(2): 125-140.

- Harkness J, Pennell B, Schoua GA (2004) Survey questionnaire translation and assessment. In: Stanley Presser (Ed.), New York, USA.

- Harkness R, van de Vijver, Mohler P (2018) Cross-cultural survey methods. John Wiley & Sons, USA.

- Henisz W, Koller T, Nuttall R (2020) Five ways that ESG creates value. McKensey Quarterly, USA.

- Honan E, Hamid M, Alhamdan B, Phommalangsy P, Lingard B, et al. (2012) Ethical issues in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 12(4): 1-14.

- Hunt SD (1993) On rethinking marketing: Our discipline, our practice, our methods Special edition on the new marketing myopia: Critical perspectives on theory and research in marketing. European Journal of Marketing 28(3): 13-25.

- Hunt D (2003) Controversy in marketing theory: For reasons, realism truth and objectivity. ME Sharpe, New York, USA.

- Jennifer R, Mick C, Judith L, Martin E, Martin J, et al. (2019) Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Wiley Online Library 546:

- Johnson T, Cho I, Shavitt S, Young Ik Cho (2005) The relation between culture and response styles: Evidence from 19 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 36(2): 264-277.

- Kenneth S (2015a) Selecting the research techniques for a method and strategy. In: Kenneth S (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of research design in business and management. Palgrave Macmillan, USA.

- Kenneth S (2015b) Developing a goal-driven research strategy. In: Kenneth S. (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of research design in business and management, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 31-47.

- Larue A (1993) Ancient ethics. In: Singer P (Ed.), A companion to ethics. Blackwell Publishers, USA.

- Levine V, West J, Reis T (1980) Perceptions of time and punctuality in the United States and Brazil. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38(4): 541-543.

- Lloyd GER (2010) History and human nature: Cross-cultural universals and cultural relativities. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 35(3-4): 201-214.

- Marshall A, Batten S (2003) Ethical issues in cross-cultural research. Connections 3(1): 139-151.

- Martin L (2008) Please knock before you enter: Aboriginal regulation of outsiders and the implications for researchers. Post Pressed.

- Murdock P (1949) Social structure. Macmillan, New York, United States.

- Osgood E (1975) Cross-cultural universals of affective meaning. University of Illinois Press, Illinois, USA.

- Padmanabhab M (2017) Transdisciplinary for sustainability. In: Padmanabhab M (Ed.), Transdisciplinary Research and Sustainability. UK, pp. 1-32.

- Zsolnai L (2003) Global impact - global responsibility: Why a global management ethos is necessary. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 3(3): 95-100.

- Zsolnai L (2015) The spiritual dimension of business ethics and sustainability management. Springer, Germany.

- Zsolnai L (2018) Progressive business models creating sustainable and pro-social enterprise. Palgrave Macmillan, UK.

© 2021 Lunevich L. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)