- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Genus 1 sp. 2 (Diptera: Chironomidae): The Potential Use of its Larvae as Bioindicators

Paula A Ossa López1, Narcís Prat2, Gabriel J Castaño Villa3, Erika M Ospina Pérez1, Ghennie T Rodriguez Rey4 and Fredy A Rivera Páez1*

1Grupo de Investigación GEBIOME, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia

2Grup de recerca consolidat F.E.M (Freshwater Ecology and Management), Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Medi Ambient, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, España

3Grupo de Investigación GEBIOME, Departamento de Desarrollo Rural y Recursos Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Caldas, Colombia

4Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Caldas, Colombia

*Corresponding author: Fredy Arvey Rivera Páez, Associate Professor, Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences, Department of Biological Sciences, Leader Research Group GEBIOME, USA

Submission: November 05, 2018; Published: November 16, 2018

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume4 Issue3

Abstract

The family Chironomidae belongs to the most abundant macroinvertebrates in samples for water quality assessment and displays a wide tolerance range to contaminants, which makes it an excellent bioindicator. The species Genus 1 sp. 2 (Chironomidae: Orthocladiinae), included among the larval keys of the Cricotopus-Oliveiriella complex, is difficult to determine based on its larval instar using the current morphological keys, which makes it necessary to use pupae for a species-level identification. In this study, 103 organisms in the IV larval instar were collected from tributaries of the high Chinchiná river basin (Caldas-Colombia), along with eight organisms at the pupal level (reared in the laboratory).

The organisms were morphologically identified, and a molecular analysis of the genes COI and 16S rDNA was performed in order to confirm and associate larvae and pupae. In the larval morphometric analysis, 13 structure measurements were taken, with the aim of finding possible variations among specimens from different sampling stations, and only dorsal head area (DHAr) showed significant differences. The presence of mentum deformities was assessed, a total of 18 specimens showed partial or total teeth deformity, although no significant differences were found between deformity frequency and the sampling stations. The results obtained allow for a molecular determination and association of larvae and pupae of the species Genus 1 sp. 2, and new morphological measurements in larvae that can aid in determining variations resulting from contaminant agents and contributing to establishing this species as a water quality bioindicator.

keywordsColombia; Deformities; Molecular analysis; Morphology; Morphometry

Introduction

The subfamily Orthocladiinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) is one of the richest in genera and species, and in Andean rivers above 2000 meters of altitude, the subfamily Orthocladiinae is very abundant, with multiple genera present in the high Andean region, and of which some have yet to be described. Furthermore, species of the same genus share many larval characteristics, making it nearly impossible to distinguish them, even at a genus level. Nevertheless, pupal forms are specific for a genus, and even for a species, and there are several records in which larvae and pupae have been associated in rivers of the high Andean region between Colombia and Peru [1].

Among the most abundant genera of Orthocladiinae in the high Andean region, there are larvae described as Genus 1 by Roback and Coffman (1983), a genus found exclusively in the Andean region. Its larvae belong to the Cricotopus-Oliveiriella complex [1,2] complicating its identification even at the genus level, and at the species-level, the differences between species have not been studied yet. Its pupae, however, are very characteristic and very different from the genus Cricotopus; therefore, a species-level description can be achieved. Larvae belonging to this taxon are abundantly found in the Chinchiná River (Colombia), and based on studies related to the association between macroinvertebrates and contamination, the possibility of using these larvae as contamination indicators has led to a complete morphological and genetic study in order to establish its possible use as bioindicators [3,4].

The use of aquatic macroinvertebrates currently constitutes a tool for the biological and integral characterization of water quality [3,5]. All aquatic organisms can be considered as bioindicators, however, the evolutionary adaptations to different environmental conditions and the tolerance limits to a given disturbance are responsible for the characteristics that classify them as sensitive organisms, whether they do not endure changes in their environment or they are tolerant to stress conditions [5,6]. Chironomidae (Diptera: Chironomidae), with nearly 20000 species distributed throughout all the continents, from the Antarctic region to the Tropics, inhabit lakes, streams and rivers during their larval and pupal developmental stages [1,7,8]. The family Chironomidae is considered to be tolerant to water contamination with organic matter, heavy metals, pesticides, aromatic polycyclic hydrocarbons, and organic solvents, displaying subletal responses such as morphological variations represented by morphometric changes and deformities as a result of exposure to these conditions [5,9-18]. Regarding these tolerance characteristics, Warwick [10], Alba-Tercedor [19], Servia [13-16], Giacometti & Bersosa [6], Arambourou [20] report Chironomidae as organisms with a potential use in water quality bioindication. Nevertheless, one of the current limitations for the use of Chironomidae is an insufficient knowledge of their taxonomy, which in many cases is not straightforward, due to phenotypic plasticity or shared characters between several species of a genus, or even between genera [1,6,21].

The present study aimed to morphological evaluation the larvae of Genus 1 sp. 2 Roback and Coffman, through diagnostic characters, further, larvae and pupae of Genus 1 sp. 2 were molecularly determined and associated based on the study of mitochondrial genes. The possible morphometric variations and record the frequency of deformities was assessed in organisms of the IV larval instar in the sampling stations (no evident anthropogenic impact or lack of any evident mining impact and sampling stations with mining impact). Overall, the results allowing to contributing to the establishment of this species as a water quality bioindicator

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study area included six sampling stations located in the Chinchiná River basin in the department of Caldas (Colombia). Two sampling stations were selected as reference (areas without an evident mining impact), one located in La Elvira stream (05°03’10.9’’ North, 75°24’33.6’’ West), municipality of Manizales, and the other in Romerales stream (04°59’22’’ North, 75°25’58’’ West), municipality of Villamaría. The other four sampling stations are impacted by waste disposal generated by gold mining [22,23]. Two of the stations were located in El Elvira stream, Manizales (05°03’4.4’’ North, 75°24’33.1’’ West; 5°1’53’’ North, 75°24’43.8’’ West), another was located in California stream, Villamaría (04°59’5’’ North, 75°26’35’’ West), and the last sampling station was in Toldafría stream, Villamaría (4°59’08’’ North, 75°26’43’’ West). The six sampling stations stood between 2275 and 2766 meters of altitude, and had similar physical habitat characteristics, such as a wavy topography and the presence of riparian vegetation.

Specimen collection

A total of six sampling events were conducted from February 2014 to February 2015. Larvae collection was carried out with a Surber net, with 30.5x30.5x8cm dimensions and a mesh size of 250μm, and manual drainers (the samples were taken from sediments, rock washes and leaf litter). The specimens were preserved in absolute ethanol with their corresponding information (date, location, and coordinates). In the laboratory, several specimens were conditioned in aquariums with water from the sampling stations, under constant oxygenation, and were fed with TetraMin® until pupae were obtained for species confirmation Table 1.

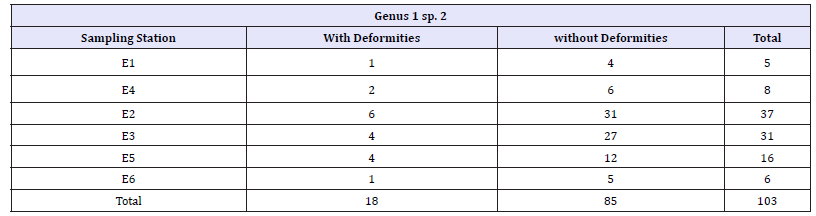

Table 1:Larvae (IV instar) of Genus 1 sp. 2 with presence or absence of deformities in each sampling station.

E1: La Elvira Stream (Reference Area); E2: La Elvira Stream (Mining); E3: La Elvira Stream (Mining), E4: Romerales Stream (Reference Area); E5: California Stream (Mining); E6: Toldafría stream (Mining)

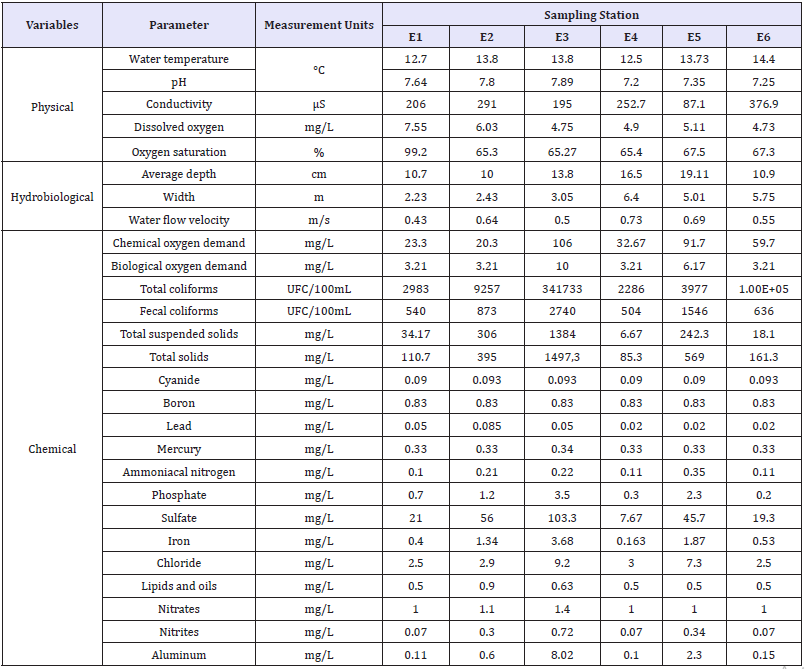

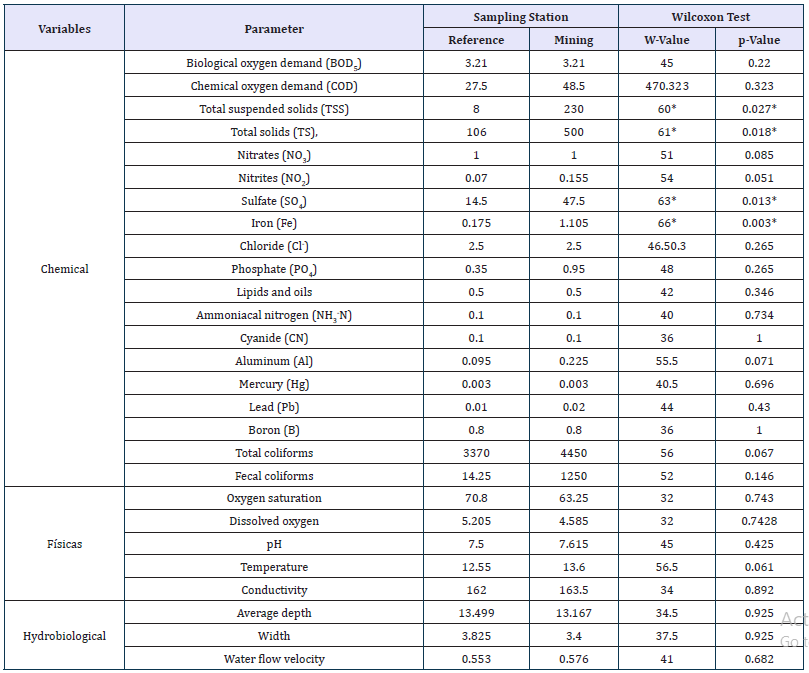

Table 2:Physical, hydrobiological, and chemical characteristics of the streams assessed. The values correspond to the mean values of the parameters measured in each sampling station (Reference stations E1 and E4. Mining impact stations E2, E3, E5 and E6).

E1-E3: La Elvira Streams; E4: Romerales Stream; E5: California Stream; E6: Toldafría Stream (Adapted from Ossa et al. [24]).

Additionally, the following physical and hydrobiological variables were measured in situ in three of the six sampling events: water temperature, pH, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, oxygen saturation, average depth, width, and water flow velocity. Also, the following chemical variables were evaluated in the laboratory: Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD5), total coliforms, fecal coliforms, total Suspended Solids (TSS), Total Solids (TS), Cyanide (CN), Boron (B), Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3-N), Phosphate (PO4), Sulfate (SO4), Iron (Fe), Chloride (Cl-), Lipids and Oils, Nitrates (NO3), Nitrites (NO2), and Aluminum (Al). These variables were analyzed by ACUATEST S.A. (Table 2). Comparisons of the physical, hydrobiological, and chemical variables between the reference and mining stations were performed using the Wilcoxon test (W).

Morphological and molecular evaluation

The ethanol-preserved organisms were examined and identified based on the keys of Prat et al. [1], using a Leica M205C stereomicroscope equipped with a MC170HD digital camera. Next, the head of each specimen, both the larvae and pupae reared in the laboratory, were dissected and placed in hot 10% KOH. They were then washed, dehydrated, and mounted on microscope slides with Euparal® for their subsequent observation, following the Light Microscopy (LM) techniques described by Epler (2001), and the head capsule and pupal keys of Prat et al. [1].

DNA was extracted from the thorax and abdomen of 11 larvae, as well as two mature pupae, using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen®), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two mitochondrial genes (mtDNA), Cytochrome Oxidase I (COI) and 16S, were amplified with polymerase chain reactions (PCR) that were conducted following Ossa et al. [24]. The PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen®), according to the manufacturer’s instruction, and were shipped for sequencing at Macrogen Inc. Korea. The sequenced fragments were evaluated and edited using Geneious Trial v8.14 [25] and Sequencher 4.1 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). In addition, the sequences were search by MegaBlast against the public databases and deposited in GenBank and Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) (Genbank accessions KY568875-KY568909).

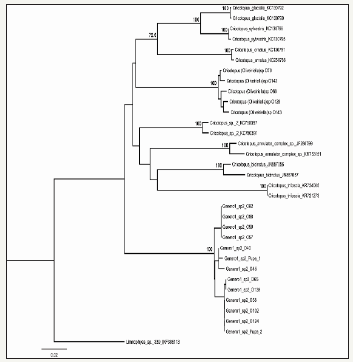

There are no available sequences for species of the Genus 1 in the public databases; therefore, the analysis of the mtDNA COI gene included sequences from eight species of Cricotopus, a genus with very similar larvae to Genus 1 [1]. The reason for including eight species from different subgenera of Cricotopus was to be able to more clearly establish the position of larvae of Genus 1 sp. 2 within the Cricotopus-Oliveiriella complex, since, similarly to what happened with the genus Oliveiriella, it is suspected that the larvae of Genus 1 of Roback are actually a subgenus within Cricotopus.

Moreover, the species Limnophyes sp. was included as an outgroup. For the mtDNA 16S rDNA gene analyses, sequences from a species of Cricotopus and the species Cardiocladius sp. were used as outgroups. The sequences for each gene were aligned using Clustal W [26], included in the program MEGA version 7 [27], and the alignments were visually reviewed and edited when necessary.

Intraspecific nucleotide divergences were estimated with the program MEGA, using the Kimura 2-Parameter distance model (K2P; Kimura 1980). Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery [28] was used to infer the number of putative species, using an intraspecific divergence prior ranging from 0.001 to 0.1 and the K2P evolutionary model. Species confirmation was carried out through a similarity analysis based on Neighbor-Joining (NJ), with the K2P model and 1000 bootstrap replications, using the program MEGA.

Larval morphometric analyses and frequency of mentum deformities

In order to find possible variations between specimens of the reference and mining stations (lack of any evident mining impact and sampling stations with mining impact), 13 structure measurements were recorded (mm or mm2 for areas), reported by Cranston & Krosch [29], Prat et al. [4] for larvae of the genus Barbadocladius (Diptera: Chironomidae) and other genera explored in this study, which were: Lateral Head Length (LH), Lateral Head Width (LHW), Lateral Head length from The Base (LHB), Thorax Length (TL), Width of III Thorax Segment (WTS), Width of IV Abdominal Segment (WAS), Total Body length (TB), Body Area (BA), Body Perimeter (BP), Dorsal Head Length (DHL), Dorsal Head Width (DHW), Dorsal Head Area (DHAr), and Dorsal Head Perimeter (DHP). The body measurements were compared between reference and mining sites, through the non-parametric Wilcoxon test (W). Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.1.1 (R Development Core Team 2011).

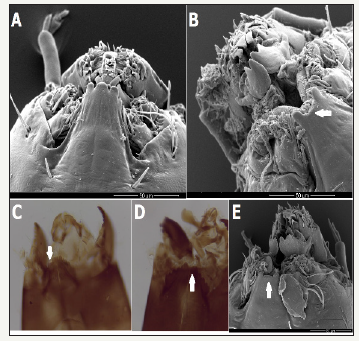

In addition, several structures were re-assessed using an electron scanning microscope (ESM). For this, the heads were mounted on stubs and metalized in gold, then; the material was analyzed and photo-documented on a FEI QUANTA 250, ESEM electron scanning microscope. The head capsule mounts with ML, as well as the ESM observations, were analyzed in order to evaluate the possible existence of mouth deformities according to the descriptions of Warwick [9] and Groenendijk et al. [30]. The association between deformity occurrence and the reference or mining stations was examined through Fisher’s Exact Test.

Result

Morphological and molecular evaluation

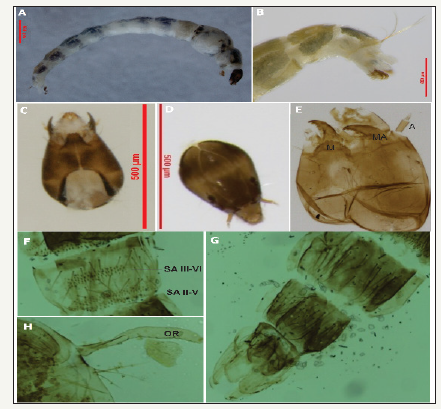

Figure 1:Genus 1 sp. 2. IV larval instar. (A) Larva in IV instar (LM); (B) Abdominal termination; (C) Head cavity (ventral view); (D) Head cavity (dorsal view); (E) Head cavity. Mentum (M), Mandible (MA), Antenna (A). 1F-H. Genus 1 sp. 2; pupae. (F) Mount of IV abdominal segment (SA). Middle spines (SA III-VI), with hooklets (SA II-V); (G) Last abdominal segments and anal lobes; (H) Respiratory organs (OR) (Light microscopy-LM).

The morphological evaluation was based on the collection of 103 organisms of the morphotype Genus 1 sp. 2 (Table 1), corresponding to the IV larval instar, as well as eight pupae reared in the laboratory. The larvae of Genus 1 are morphologically characterized by a white colored body in young larvae, and darker areas in the thorax in more mature larvae. However, it has been noted that color variations cause difficulties for species determination [31]. Fourth instar larvae of Genus 1 sp. 2 show equal abdominal setae of length corresponding to half of the width of the abdominal segment, and anal tubules shorter than the posterior pseudopods.

Head with no pattern, very dark solid color with lighter areas close to the lateral border in the frontal and medial sections; very dark occipital border (Figure 1) and short antennae. Mentum with second lateral tooth smaller than the first; first lateral tooth as wide as second and narrower in the lower part (Figure 1 & 2). Mandible with upper tooth shorter and narrower than the first.

Figure 2:Genus 1 sp. 2. Head cavity, arrows indicate teeth deformities in the mentum. (A) Mentum without deformities-ESM; (B, E) Total loss of several dental pieces - ESM; (C) Teeth wear-LM; (D) Total loss of several dental pieces-LM (Light microscopy-LM and electron scanning microscopy-ESM).

In the eight pupae evaluated, terga ornamentation showed two rows of anteriorly-oriented spines in the II-V abdominal segments (SA); anal lobe reduced, with a similar size to the genital sacs (Figure 1). Respiratory organ (OR) rounded at the end and often with diverse folds on the surface (Figure 1) and without middle spines in the II tergite, although present in the III-VI terga.

In addition, the molecular alignment analyses of the fragments of the mtDNA COI and 16S rDNA genes, respectively, confirmed the results obtained by the morphological determination. Based on the initial partition and an intraspecific divergence prior between 0.001 and 0.1 for the COI gene and between 0.0028 and 0.0599 for the 16S gene, the ABGD species delimitation method identified that the larval and pupal sequences obtained for Genus 1 sp. 2 belong to a single species out of the nine species identified with the COI gene and the two species identified with the 16S gene.

Figure 3:Consensus NJ tree with samples of Genus 1 sp. 2, based on distances of the mtDNA COI gene. Bootstrap values are indicated only for nodes with support greater than 70%.

Furthermore, the consensus trees obtained from the two genes, based on the Neighbor-Joining method, clearly show that the larval and pupal sequences of Genus 1 sp. 2 constitute a well-supported monophyletic clade, with a mean intraspecific divergence of 0.95%, based on the COI gene (Figure 3), and 0.11% on the 16S gene (Figure 4). These intraspecific divergence values observed for Genus 1 sp. 2 are similar to the mean values found for the Cricotopus species analyzed; with 0% for C. trifascia and 2.31% for C. bicinctus with the COI gene, and 0.20% para Cricotopus (Oliveiriella) with the 16S gene.

Figure 4:Consensus NJ tree with samples of Genus 1 sp. 2, based on distances of the mtDNA 16S gene. Bootstrap values are indicated only for nodes with support greater than 70%.

The intraspecific divergence values found between the species analyzed varied between 4.73% and 19.2% with gene COI; while the observed divergence between Genus 1 sp. 2 and Cricotopus (Oliveiriella) with gene 16S is 7.49%.

Larval morphometric analyses and frequency of mentum deformities

Of the 13 structure measurements assessed, significant differences were observed only for dorsal head area (DHAr) between the specimens found in the reference and mining stations, according to the non-parametric Wilcoxon test (W=382,5, p=0,04).

Mentum deformities were observed in 18 of the 103 specimens evaluated. Partial wear of the teeth was evident, as well as total wear or tooth loss (Figure 2). Nevertheless, no significant differences were found for deformity occurrence in relation to the reference and mining stations (Fisher’s Exact Test, p=0.669). Of the total organisms collected in the reference stations, 23.1% showed deformities, indicating that these sampling stations have some type of anthropic impact, as evidenced by the physical, hydrobiological, and chemical analyses, where most of the parameters assessed do not show differences between the reference and mining stations (Table 3). Additionally, there were differences in organism abundance of Genus 1 sp. 2 in relation to the reference and mining stations (Table 1). The organisms from Genus 1 sp. 2 showed a greater abundance in stations with mining (n=90) compared to the reference stations (n=13).

Table 3:Wilcoxon Test comparing the parameters measured (medians are shown) between reference stations (E1 and E4) and mining impact stations (E2, E3, E5, and E6).

*Differences

Discussion

The morphological evaluation was based on 103 larvae and eight pupae of Genus 1 sp. 2, and all morphological characteristics agree with those reported by Prat et al. [1-3]. Although, some of the characteristics previously mentioned appear in many larval forms, including the genus Cricotopus, of which several subgenera and morphotypes, along with the Genus 1, are included in keys of the Cricotopus-Oliveiriella complex [1]. Therefore, it is almost impossible to differentiate them at the species level based on a larval instar [8]. However, this morphology is associated with very different pupal forms, which allowed us to reach a species level determination, following the key of Prat et al. [1] and the indications of the original description of pupae for Genus 1 sp. 2 in Roback & Coffman [32]. Prat et al. [1] report that it is common to find Genus 1 in pupae forms in high Andean rivers, where these are very characteristic and very different from Cricotopus.

The molecular results confirmed the morphological determination, previous studies have reported interspecific distances for Diptera similar to those reported here; Shouche & Patole [33] observed interspecific distances with gene 16S between 1% and 9% in three species of Diptera. Ekrem et al. [34] reported interspecific divergences of 16.2% for gene COI in the family Chironomidae. However, this reference value for species identification is not enough, given that these studies mainly comprise specimens from the Holarctic region, and there are still few studies that analyze specimens from the Neotropics, including members of the subfamily Orthocladiinae.

The comparison of the molecular data of Oliveiriella and Genus 1 with other subgenera of Cricotopus confirms the findings of Andersen et al. [35], which are also confirmed by Prat et al. [1] in that Oliveiriella is a subgenera of Cricotopus and Genus 1 of Roback and Coffman is also a subgenera.

Nevertheless, the larval measurements have been used to differentiate larval instars and sexual dimorphism [36,37], pupal and exuviae stages [2,29], exposure to contaminant agents by evaluating size variations in head parts [9,13-16,30,38], and morphometric variations in adults in different regional gradients [39]. In this study, only dorsal head area (DHAr) is informative; therefore, more research is necessary in order to determine if the differences found in this study are due to genetic variability, stress type (essential and/or toxic substances), the structures studied or the morphometric data used, or to a combination of all of these variables [13,18,40].

Although no significant differences were found between deformity frequency and the sampling stations. The presence of deformities in Chironomidae larval instars is considered to result from exposure of these organisms to diverse contaminant agents [13,18,40]. Due to their tolerance, Chironomidae are considered excellent water quality bioindicators, since they have regulation mechanisms for metals such as Cu, Ni, Zn, Cd, Pb, Hg, and Mn, and for which they employ a homeostatic control for the uptake of essential and toxic metals through metallothioneins [17,20,41,42]; consequently, allowing them to survive in contaminated conditions [43].

A great amount of total and suspended solids was found, with a high content of sulfates and metals such as Iron (Fe), which are characteristic of mining disposals and can have negative effects on exposed organisms [44]. Nevertheless, according to Arambourou et al. [18], there is missing information regarding the study of the origin of these abnormalities. Servia et al. [13] and Arambourou et al. [18] mention that, to date, there are no studies that allow for discarding the possibility that this type of malformations appear spontaneously due to natural developmental defects. Further, it cannot be ignored that changes in the mentum can be due to the substrate or contamination [40,45].

Considering that genera of the order Diptera are typical of disturbed areas [3], Genus 1 sp. 2 can be considered as having potential for water quality bioindication, due to its tolerance to environmental stress, similar to other species of the family Chironomidae [6,9,13,20].

Finally, the results obtained allow the molecular determination of Genus 1 sp. 2 (Roback and Coffman), support the morphological data, and associate larvae and pupae, contributing to a better understanding of the taxonomical limits in Chironomidae, specifically the subfamily Orthocladiinae, where there are many difficulties in the taxonomic determination of its species [8,21,43,46-52]. Moreover, the results support the establishment of this species as a water quality bioindicator [53-56].

Acknowledgment

To the members of the Research Group GEBIOME, the Institute IIES, the Laboratory of Microbiology, and the Entomological Collection of the Biology Program of the Universidad de Caldas (CEBUC). To COLCIENCIAS for financing the project “Assessment of impacts of mining, agriculture and livestock farming through ecological and genetic responses of aquatic macroinvertebrates” (Grant 569/2016).

References

- Prat N, Acosta R, Villamarín C, Rieradevall M (2011) Guía para el reconocimiento de las larvas de Chironomidae (Diptera) de los ríos altoandinos de Ecuador y Perú. Clave para la determinación de los géneros.

- Prat N, Acosta R, Villamarín C, Rieradevall M (2012) Guía para el reconocimiento de las larvas de Chironomidae (Diptera) de los ríos Altoandinos de Ecuador y Perú. Clave para la determinación de los principales morfotipos larvarios.

- Zúñiga MC, Cardona W (2009) Bioindicadores de calidad de agua y caudal ambiental. In: Cantera J, Carvajal MY, Castro LM (Eds.), Caudal Ambiental, Conceptos, Experiencias y Desafíos, Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, USA, pp. 167-196.

- Prat N, Ribera C, Rieradevall M, Villamarin C, Acosta R (2013) Distribution, abundance and molecular analysis of Barbadocladius Cranston and Krosch (Diptera, Chironomidae) in tropical, high altitude Andean streams and rivers. Neotropical Entomology 42: 607-617.

- Roldán G (1999) Macroinvertebrates and their value as indicators of water quality. Journal of the Colombian Academy of Exact Sciences. Físicas y Naturales 23: 375-387.

- Giacometti JCV, Bersosa FV (2006) Aquatic macroinvertebrates and their importance as bioindicators of water quality in the Alambi river. Technical Bulletin 6, Zoological Series 2: 17-32.

- Ekrem T, Willassen E (2004) Exploring tanytarsini relationships (Diptera: Chironomidae) using mitochondrial COII gene sequences. Insect Systematic and Evolution 35: 263-276.

- Sari A, Duran M, Bardakci F (2012) Discrimination of orthocladiinae species (Diptera: Chironomidae) by using cytochrome c oxidase subunit I. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica 4: 73-80.

- Warwick WF (1985) Morphological abnormalities in Chironomidae (Diptera) larvae as measures of toxic stress in freshwater ecosystems: Indexing antennal deformities in Chironomus Meigen. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 42(12): 1881-1914.

- Warwick WF (1990) The use of morphological deformities in chironomid larvae for biological effects monitoring, Inland Waters Directorate, National Hydrology Research Institute, National Hydrology Research Centre, Environment Canadá, Canada.

- Madden CP, Suter PJ, Nicholson BC, Austin AD (1992) Deformities in chironomid larvae as indicators of poliution (pesticide) stress. Netherlands Journal of Aquatic Ecology 26(2-4): 551-557.

- Dickman M, Rygiel G (1996) Chironomid larval deformity frequencies, mortality and diversity in heavy-metal contaminated sediments of a Canadian riverine wetland. Environment International 22(6): 693-703.

- Servia MJ, Cobo F, González MA (1999) On the possible repercussion of the presence of deformities in the life cycle of Chironomus riparius Meigen, 1804 (Diptera, Chironomidae). Bulletin of the Spanish Entomology Association 23: 105-113.

- Servia MJ, Cobo F, González MA (1999) Appearance of deformities in larvae of the genus Chironomus (Díptera, Chironomidae) collected in undisturbed environments. Bulletin of the Spanish Entomology Association 23: 331-332.

- Servia MJ, Cobo F, González MA (2000) Seasonal and interannuaí variations in me frequency and severity of deformities in larvae of Chironomus riparias Meigen, 1804 and Prodiamesa olivácea (Meigen, 1818) (Díptera, Chironomidae) collecled in apolluted site. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 64: 617-626.

- Servia MJ, Cobo F, González MA (2000) Incidence and causes of deformities in recently hatched larvae of Chironomus riparius Meigen, 1804 (Díptera, Chironomidae). Archiv für Hydrobiologie 349: 387-401.

- Iannacone OJA, Salazar CN, Alvarino FL (2003) Variability of the ecotoxicological test with chironomus calligraphus goeldi (Diptera: Chironomidae) to evaluate Cadmium, mercury and lead. Ecol Apl 2(1): 103-110.

- Arambourou H, Beisel JN, Branchu P, Debat V (2012) Patterns of fluctuating asymmetry and shape variation in Chironomus riparius (Diptera, Chironomidae) exposed to nonylphenol or lead. PLoS ONE 7(11): e48844.

- Alba TJ (1996) Aquatic macroinvertebrates and water quality of rivers, in IV Water symposium in Andalusia (SIAGA)-Almería II, pp. 203- 213.

- Arambourou H, Gismondi E, Branchu P, Beisel JN (2013) Biochemical and morphological responses in Chironomus riparius (Diptera, Chironomidae) larvae exposed to lead-spiked sediment. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 32(11): 2558-2564.

- Silva FL, Wiedenbrug S (2014) Integrating DNA barcodes and morphology for species delimitation in the Corynoneura group (Diptera: Chironomidae: Orthocladiinae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 104(1): 65-78.

- Bastidas TJC, Ramírez OLC (2007) Determination of the polluting load of industrial origin poured on the Quebrada Manizales, thesis, Manizales, Caldas, Colombia, USA.

- Jiménez PP, Toro RB, Hernández AE (2014) Relación Entre La Comunidad De Fitoperifiton Y Diferentes Fuentes De Contaminación En Una Quebrada De Los Andes Colombianos: Relación Fitoperifiton Y Contaminación Ambiental. Bol Cient Mus Hist Nat Univ Caldas 18(1): 49-66.

- Ossa LPA, Camargo MMI, Rivera PFA (2018) Andesiops peruvianus (Ephemeroptera: Baetidae): A species complex based on molecular markers and morphology. Hydrobiologia 805: 351-364.

- Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Cheung M, Heled J, Kearse M, et al. (2009) Geneious version 8.14.

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG (1997) The CLUSTAL X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 4876-4882.

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA 6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30(12): 2725-2729.

- Puillandre N, Lambert A, Brouillet S, Achaz G (2012) ABGD, automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Mol Ecol 21(8): 1864-1877.

- Cranston PS, Krosch M (2011) Barbadocladius cranston and krosch, a new genus of Orthocladiinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) from South America. Neotropical Entomology 40(5): 560-567.

- Groenendijk D, Zeinstra LWM, Postma JF (1998) Fluctuating asymmetry and mentum gaps in populations of the midge Chironomus riparias (Diptera: Chironomidae) from a metal-contaminated river. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 17(10): 1999-2005.

- Gresens SE, Belt KT, Tang JA, Gwinn DC, Banks PA (2007) Temporal and spatial responses of Chironomidae (Diptera) and other benthic invertebrates to urban stormwater runoff. Hydrobiologia 575: 173-190.

- Roback SS, Coffman WP (1983) Results of the catherwood bolivianperuvian altiplano expedition. Part II. Aquatic Diptera including montane Diamesinae and Orthocladiinae (Chironomidae) from Venezuela. Proceedings of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 135: 9-79.

- Shouche Y, Patole M (2000) Sequence analysis of mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA gene fragment from seven mosquito species. Journal of Biosciences 25(4): 361-366.

- Ekrem T, Willassen E, Stur E (2007) A comprehensive DNA sequence library is essential for identification with DNA barcodes. Mol Phylogenet Evol 43(2): 530-542.

- Andersen T, Sæther OA, Cranston, PS, Epler JH (2013) The larvae of Orthocladiinae (Diptera: Chironomidae) of the Holarctic region-9. Keys and diagnoses, in Chironomidae of the Holarctic Region: Keys and diagnoses, Part 1. In: Larvae T, Andersen PS, Cranston, Epler JH (Eds.), Insect Systematics and Evolution Supplements, pp. 137-144.

- Atchley WR, Martin J (1971) A morphometric analysis of differential sexual dimorphism in larvae of Chironomus (Diptera). Canadian Entomologist 103(3): 319-327.

- Richardi VS, Rebechi D, Aranha JMR, Navarro SMA (2013) Determination of larval instars in Chironomus sancticaroli (Diptera: Chironomidae) using novel head capsule structures. Zoologia 30(2): 211-216.

- Epler JH, Cuda JP, Center TD (2000) Redescription of Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae), a potential biocontrol agent of the aquatic weed Hydrilla (Hydrocharitaceae). Florida Entomologist 83(2): 171- 180.

- Gresens SE, Stur E, Ekrem T (2012) Phenotypic and genetic variation within the Cricotopus sylvestris species-group (Diptera, Chironomidae), across a Nearctic-Palaearctic gradient. Proceedings of the 18th International Symposium on Chironomidae Fauna Norvegica 31: 137- 149.

- Langer JM, Köler HR, Gerhardt A (2010) Can mouth part deformities of Chironomus riparius serve as indicators for water and sediment pollution? A laboratory approach. Journal of Soils and Sediments 10: 414-422.

- Fowler BA (1987) Intracellular compartmentation of metals in aquatic organisms: Roles in mechanisms of cell injury. Environ Health Perspect 71: 121-128.

- Krantzberg G, Stockes PM (1989) Metal regulation, tolerance and boby burdens in the larvae of the genus Chironomus. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 46(3): 389-398.

- Sinclair CS, Gresens SE (2008) Discrimination of cricotopus species (Diptera: Chironomidae) by DNA barcoding. Bulletin of Entomological Research 98(6): 555-563.

- Aduvire O (2006) Acid drainage of mine generation and treatment. Geological and Mining Institute of Spain, Directorate of Mineral Resources and Geoambiente, Madrid, Spain.

- Bird GA (1997) Deformities in cultured Chironomus tentans larvae and the influence of substrate on growth, survival and mentum wear. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 45(3): 273-283.

- Lin X, Stur E, Ekrem T (2015) Exploring genetic divergence in a speciesrich insect genus using 2790 DNA Barcodes. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138993.

- Montagna M, Mereghetti V, Lencioni V, Rossaro B (2016) Integrated taxonomy and DNA barcoding of Alpine Midges (Diptera: Chironomidae). PLoS ONE 11(3): e0149673.

- Epler JH (2001) Identification manual for the larval Chironomidae (Diptera) of North and South Carolina: A Guide to the Taxonomy of the Midges of the Southeastern United States, Including Florida. North Carolina Department of Environmental and Natural Resources, Division of Water Quality, pp. SJ2001-SP13.

- Ann Arbor, Gene Codes Corporation, Michigan, Sequencher® version 4.1 sequence analysis, USA.

- Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution 16(2): 111-120.

- Pan B, Chattopadhyay S, Majumdar U (2016) Assessment of insecticide toxicity in Rice fields by mouth part deformities in chironomid larvae (Diptera: Chironomidae). International Journal of Scientific Engineering and Applied Science 2(2): 411-419.

- Prat N, González TJD, Ospina TR (2014) Clave para la determinación de exuvias pupales de los quironómidos (Diptera: Chironomidae) deríos altoandinos tropicales, Revista Biología Tropical 62: 1385-1406.

- Prat N, Paggi A, Ribera C, Acosta R, Ríos TB, et al. (2018) The Cricotopus (Oliveiriella) (Diptera: Chironomidae) of the High-Altitude Andean Streams, with Description of a New Species, CO. rieradevallae Neotropical Entomology 47(2): 256-270.

- R Development Core Team (2011) A language and environment for statistical computing: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Adapted (2018) Physical, Hydrobiological, Chemical characteristics of the streams assessed. The values correspond to the mean values of the parameters measured in each sampling station (Reference stations E1 and E4. Mining impact stations E2, E3, E5 and E6). E1-E3: La Elvira streams, E4: Romerales stream, E5: California stream, E6: Toldafría stream, California stream, USA.

- Wilcoxon Test comparing the parameters measured (medians are shown) between reference stations (E1 and E4) and mining impact stations (E2, E3, E5, and E6).

© 2018 Fredy Arvey Rivera Páez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)