- Submissions

Full Text

Degenerative Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities

Intellectual Disability, Childhood Overweight and Obesity

Ray Marks1,2*

1Department of Health, Physical Education, Gerontogical Studies & Services. York College, City University of New York, USA

2Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, USA

*Corresponding author: Marks R, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, Box 114, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA

Submission: December 07, 2017; Published: December 18, 2017

Volume1 Issue1 November 2017

Abstract

Exercise, a vital health-promoting activity, regardless of health status, is often recommended for helping to prevent or reduce the onset and progression of obesity, a major global health concern. Yet, even though youth with disabilities may be at a high risk for obesity, little effort seems to be applied towards encouraging the use exercise among youth with intellectual or developmental disabilities. This brief attempts to explain why obesity prevention is needed and how to promote this among this special needs group of youth, where participating in physical activity and sustaining this is very challenging.

Keywords: Developmental disability; Exercise; Intellectual disability; Overweight; Obesity; Prevention; Physical activity; Youth

Background

Intellectual disability [ID], a widespread developmental disability affecting many of today's youth is probably an underestimated risk to the individual's overall health status. In particular, in addition to their characteristic cognitive and educational challenges, as well as regular life challenges, those with ID may be at high risk for a variety of chronic illnesses and syndromes, which could limit their life quality as well as longevity, while heightening their inability to independently carry out functions of daily living due to their diminished capacity to understand and act on complex matters that have health implications.

One of these health issues and one that is clearly very pervasive in both healthy children as well as those with ID is childhood overweight or obesity [1-4]. As recounted in numerous publications, obesity continues to pose an immense health problem of concern in all parts of the globe with few exceptions due to its rising overall prevalence, and its excess prevalence among children with ID is no exception. Commonly attributed to an excess of sedentary behaviors coupled with the excess ingestion of foods laden with sugar and fats, the risk for childhood obesity is imperative to combat in instances where barriers to physical activity, as well as barriers to healthy foods exist as the norm. Not only associated with social stigmas, childhood obesity produces an excess burden of mental health correlates such as low self-esteem, along with an increased risk of several chronic diseases, such as diabetes type 2. An elevated weight status, often more common than not in youth with ID is also the leading risk for increased rates of morbidity and mortality among adults with ID [4].

Consequently, identifying and resolving this issue early, while imperative for all children, is of added magnitude in importance for the child with an ID classification, who is at high risk for overweight and its consequences and a reduced ability to reverse this condition over time. In addition to the multiple challenges in reversing any overweight state during the adolescent or adult years, under normal situations, youth with an ID classification may be at higher risk than their healthy counterparts simply because they commonly spend considerable time in remediation, watching television or playing videogames, rather than playing in parks, or joining in physical education, team outdoor sports or indoor sports [4].

Indeed, research shows, those with severe ID levels, those with degenerative developmental disabilities, those who are sedentary, and those with Down syndrome or autism may be at particularly high risk in this regard [5]. Moreover, those experiencing physical distress from accompanying medical problems may show increases in behavioral problems [6], and a need for pharmacologic interventions that may impact appetite control negatively, among other factors [4]. According to Ranjan et al. [7], the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults with intellectual disability ranges from 28%-71% and 17%-43%, respectively.

The concern in this particular essay is that among the reversible causes of childhood obesity, including the nature of the built environment, the intake of unhealthy food sources, and health policies that favor the sale of sugary products, efforts to protect youth from the marketing of fast foods and sugar related products, that can be addictive are insufficient at best, and may be inadequate to meet the needs of reducing childhood obesity in children with ID or developmental challenges or both. As well, although much emphasis is placed on raising physical activity levels and reducing sedentary behaviors among youth and young children, because obesity among youth and others is largely attributed to the excess intake of foods, coupled with too little exercise, rather than contextual factors alone [7], the specific needs of children with ID in this respect may warrant more attention than the mainstream in our view to reduce gaps in health outcomes attributable to this reversible or preventable factor.

To better understand the scope of this issue, how much work has been done in this realm, what best practices might look like, and what barriers exist to intervening in this area, we undertook an environmental scan. The goal was to examine what exists, and what might be helpful for advancing our awareness and directions in the future in preventing excess weight gain in the early life of the child with ID or delayed development challenges or both.

Methods

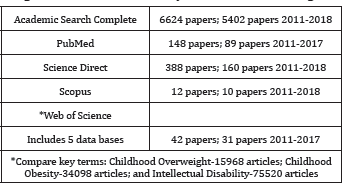

The sources examined were PUBMED, Web of Science, Academic Search Complete, Science Direct, and Scopus using the terms Intellectual Disability and Childhood Overweight or Obesity All English language publications were eligible, but the focus was on 2011-2015 data sources. The author's insights are added as well. This brief is thus not a systematic or comprehensive review by any means, and is simply an exploration of a little studied health issue in an effort to discern if more attention and action should be devoted to this topic by researchers, educators, caregivers, and clinicians. All forms of publication and research were deemed acceptable if they addressed the key issues and questions, namely: is overweight a problem in ID children; is physical activity a factor that is heightening the risk of childhood obesity in ID; and are there practical solutions for addressing this issue-if the obesity risk among this group is supported. Other topics were not considered. The focus on physical activity as a determinant of childhood weight status, was selected for specific review since it is the leading health indicator believed to underpin the childhood obesity epidemic. It also offers a remedy that can be incorporated into a child’s daily life, with little or no additional monetary expense to the family.

After reviewing the websites mentioned above, all articles deemed relevant were downloaded and read thoroughly and those that were believed most pertinent were reviewed and divided into four broad categories that depict the key topics of interest and that emerged from this body of literature. As seen below, these include the prevalence and outcomes of ID childhood overweight, the possible causes of childhood obesity, the nature of physical activity in the context of obesity prevention, and some solutions for reducing the risk of early weight problems in the context of ID. In all cases, the data bases had to be examined very carefully, as many articles that were deemed to fulfill the keywords were unrelated to the topic or addressed obesity in general, or ID in general.

Data Base Findings

The sources examined which housed the following numbers of articles, showed a very modest interest in this topic area, when compared to the related body of literature. Many articles too appeared in more than one data base, or were irrelevant to the topic of interest (Table 1).

Table 1: Listings of Numbers of Papers Found at Major Data Bases using Terms ‘Intellectual Disability and Childhood Overweight’.

Overweight among children with ID

As outlined above, youth with an ID diagnosis may be especially vulnerable to becoming overweight [8], particularly if they have associated physical challenges, and certain genetic risks for obesity and metabolic problems [4,9] that render them less active than able bodied youth. As well, they may be less able to render careful decisions about food choices in the face of an unhealthy food environment and food selection norms than their healthy age matched counterparts. They may also have less experience with choosing correct foods, helping parents to cook healthy meals, and especially with socializing with healthy active youngsters. If already obese, or diabetic, or both, they may feel too lethargic to carry out desired levels of exercise, especially if they feel challenged mentally in this regard. This subgroup of youth may also spend more time using technology than average children if they are socially isolated as a result of their mental health condition, or a lack of self-efficacy for exercising [4]. Parents or caregivers too, might feel their children with ID are safer inside the home, and may be protective of them if they wish to pursue exercises in the community.

Basil et al. [5] argued that more aggressive weight management in early childhood of Down’s Syndrome should be forthcoming because of the high obesity risk of this group. These recommendations seem justified given their findings, plus findings of Emerson et al. [8] that children with ID account for 5-6% of all obese children. It further appears that children with ID who do not exercise are much more likely to gain weight than those who do not, even if the foods they eat are nutritious. In addition, as with healthy children, children with ID may overeat to cope with their many life challenges or their poor methods of dealing effectively with their emotions, such as anxiety. Their food choices might be addictive, and guided by habit, as with healthy children, and be amplified due to a lack of suitable nutrition education efforts [9]. Unsurprisingly, Peterson et al. [10] found that while physical activity (steps/day) achieved by the majority of the population studied was insufficient for health benefits, most severely compromised in this regard were individuals with moderate intellectual disabilities.

Another problem is that if the family itself includes overweight members, and being 'large' seems to be the norm, children with ID may not be able to perceive their obesity problem accurately. Moreover, having parents or guardians who commonly buy groceries from convenience stores, such as cookies, chips and other high- calorie items, as well as foods from fast food chains, the likelihood of an undesirable increase in the child's weight is increased. Although pediatricians can help to identify this situation, not all pediatricians may do this [9], and not all parents have a regular provider, or believe their child is at risk even if this is indicated. Body weight and health may also be less of a concern to caregivers than other factors such as behavioral problems. According to Bandini et al. [9], another key factor is that children and youth with disabilities, may experience limitations that influence access to physical activity and proper nutrition, such as living in the same obesogenic environment as other children.

Health effects of childhood obesity

The term childhood obesity, commonly referring to a situation where a child is well above the normal weight for his or her age and height, is clearly an immense global problem that is greatly magnified in the individual with ID. Reaching beyond epidemic proportions, ample research shows the presence of obesity, presently considered a serious medical condition in its own right, has multiple adverse health outcomes, as well as multiple economic and social ramifications, and can greatly impact the individual with ID [2] who clearly is more vulnerable than not. Indeed, regardless, of diagnostic ID category, childhood overweight or obesity has both severe frequently irreversible immediate and long-term effects on both health and well-being, and probably on academic achievement indirectly, given the link between exercise and cognition.

Some immediate outcomes include:

a) A high risk of incurring cardiovascular diseases, such as high cholesterol or high blood pressure, and pre-diabetes, which can lead to the presence of definitive diabetes in adult hood.

b) A high risk of bone and joint problems, sleep apnea, and social and psychological problems such as stigmatization and poor self-esteem.

Asthma, non alcoholic fatty liver disease, and psychological ramifications, including less ‘acceptance’ of obese children [4].

Long-term health outcomes include:

a) Becoming obese adults at risk for adult health problems such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, several types of cancer, and painful disabling osteoarthritis.

b) Other problems include mobility limitations, falls injuries, poor bone health, and chronic pain from osteoarthritis [11,12].

Preventing childhood obesity

Prevention efforts for youth with ID, who are prone to overweight and obesity [13-15] are not unlike those for healthy children. These include, but are not limited to the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits, including healthy eating and physical activity. In this regard, by establishing a safe and supportive environment with policies and practices that support healthy behaviors, schools can play a particularly critical role. Schools can also provide opportunities for students with ID to learn about and practice healthy eating and physical activity behaviors [16]. In addition to the school, caregivers in the home, or residential settings or group homes can play a key role in this regard [17]. Outpatient programs in the community, and those conducted by nurses also appear to hold promise, while adapting youth-related obesity prevention programs to account for the challenges and abilities of the individual child with an ID diagnosis also appears worthy of consideration [17].

In summary, overweight and obesity in childhood [including adolescence] is associated with serious long-term physiological, psychological, and social consequences. Even more disturbing, is that this is especially so among youth with intellectual or developmental challenges, as outlined in the recent literature [17]. This may clearly reduce their overall life quality even more profoundly than anticipated by their disability, as well as reduce longevity markedly, unless addressed in a dedicated manner. We hence concur with Basil et al. [5] who examined obesity among adults with Down syndrome that more aggressive weight management in early childhood and throughout the lifespan of the individual with ID, including Down's Syndrome is imperative, with a special focus on physical activity promotion.

Role of physical activity

Physical activity, important for the health and well-being of all, is defined as any body movement that uses the muscles and requires the use of more calories than when the muscles are not moving. Some examples of common everyday physical activities are walking, jogging, biking, dancing, swimming, tennis, and gardening. Physical activity can also be carried out as part of one's recreational activities, work activities, and house chore activities, and does not have to be formally structured. Exercise is however, a form of physical activity.

Ample research shows, physical activity is of high importance because physical inactivity, or too little physical activity is a leading risk factor for chronic diseases, premature death and disability. In addition to being the key cause of many common diseases such as breast and colon cancers, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease burden, youth who do very little physical activity may find it hard to regulate their weight. On the other hand, children who participate in regular physical activity, including those with ID can potentially:

a. Reduce the risk of incurring high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke [18], diabetes, breast and colon cancer, depression, anxiety, and falls;

b. Improve their bone and muscle strength, as well as their ability to function physically [1].

c. Increase their energy supply, and reduce fatigue, as well as excess weight, and body fat.

d. Increase their chances of living longer.

e. Lower the number of doctor visits they need.

f. Promote their psychological well-being, self-esteem, and quality of life.

g. Promote their academic performance.

h. Improve their self-discipline, and socialization skills.

The best way to encourage physical activity is probably by using a small steps approach towards the desired activity level, especially for those with a debilitating health condition or those who are extremely deconditioned. Physical activity tailored to the individual’s ability and health status can then be pursued accordingly in the school, community, or home settings. About 3060 minutes of moderate physical activity five days a week or more is recommended, and parents and caregivers should be vigilant to reduce inactivity levels-most commonly observed in evenings or weekends among persons with ID [10].

To prevent boredom and increase the value of exercising, the use of multiple and diverse types of physical or adapted activities are encouraged. In addition, to encourage adherence to physical activity, pleasant activities that can be carried out regularly can be helpful. However, because low physical fitness that results from sedentary behaviors may be the key factor that leads to obesity among children with ID and others [1], any form of physical activity is likely to be better than no physical activity. On the other hand, Heller and Sorenson [11] found that studies that have focused on both exercise and nutrition health education have tended to show positive weight change benefits, changes in health behaviors attitudes and to some degree, life satisfaction [11].

Lobenius-Palmer K et al. [19] found that youth with autism diagnoses were least physically active among sub-groups of youth with disabilities, ages 7-20, suggesting this group needs very concerted observation and assistance even into the higher age ranges. As outlined by Ptomey et al. [20], evidence does show that increasing physical activity, self-monitoring diet and attending educational or counseling sessions during monthly home visits can yield clinically meaningful weight losses among adults with ID. Hinckson et al. [21] found parents of children and youth with ID that took part in an integrated physical activity and nutrition program commented that during the program there were less hospital visits and absences from school related to illness. The program also assisted in the development of a supportive community network and participants’ abilities to partake in family and community activities.

Other data show positive benefits might accrue from a multicomponent exercise program [18], cross-circuit exercise training efforts [22], walking using an air mouse combined with preferred stimulation [23], and efforts to improve self-efficacy for leisure time activity [24].

Since those children with ID whose parents are obese [25,26], along with those with a high salt intake, those who were not breastfed, those with mothers who gave birth and were over 30 years of age, those with large families, low monthly incomes, and low level of parents' education are at highest risk of childhood and adult obesity, it seems these groups should be specifically targeted and carefully monitored over extended time periods [25].

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Multiple data sources confirm childhood overweight is an unrelenting public health challenge that shows few signs of abating. Moreover, regardless of where the research is conducted, additional research shows not only are many preventable diseases associated with the early onset of obesity, but that this risk increases incrementally as the magnitude of an individual’s obesity level and ID level of disability increases [15-19,26].

Given that high rates of overweight in the early childhood years are not only more marked in youth with ID than healthy youth [27], and may average from 15% for overweight to 30% for overweight- obesity diagnoses [28], and that situation does not seem to wane in any significant way in adolescence, where high rates prevail [26], and adolescents with ID are 1.54 and 1.80 times more likely to be at risk for overweight or obesity than typically developing children [28], clearly much more needs to be done to impact this specific problem at the outset for this vulnerable population. Given that current community wide campaigns designed to minimize this immensely burdensome public health problem have made marginal impacts to date, and public health programs are less likely to be useful for ID youth than those who are healthy, placing more emphasis on local family and school-based health promotion efforts specifically targeted and tailored for the needs of youth with ID [12,13,16] may be one area where a more systematic and concerted effort can begin to combat the tendency towards excess body mass associated with low rates of physical activity participation this ID sub-group [11,26,28-30].

In particular, parents, who have great influence over their children’s health practices may want to engage their children in activities that are enjoyable and easy to accomplish on a regular basis, bearing in mind that this commitment may make the difference between a high versus a marginal life quality for their child later on. They can also help by consistently setting a healthy example and attending mindfully to what is purchased and eaten in and out of the home, while encouraging their children to participate in shopping expeditions, food label deciphering, and food preparation processes.

In addition, parents and caregivers of the ID child may not realize:

a. Social media, when used for excessive periods poses an increased risk for the early onset of childhood obesity.

b. Soft drinks and fruit juices can be calorie laden and sugar can be addictive;

c. High salt intake too is associated with increased overweight risk [25];

d. Getting children to move is as important as their cognitive development;

e. Children who are overweight may be bullied and ostracized by their peers;

f. Children are strongly influenced by marketing messages about fast foods;

g. Medications used to treat ID problems are often appetite altering [4];

h. Some genetic disorders render movement difficult and distort eating habits [4];

i. Parents own habits and overweight situations contribute to childhood weight problems [26].

Unsurprisingly, Sleven et al. [31] found over a quarter of foods consumed by Northern Ireland school children were fatty and sugary foods and close to 30% of these foods were eaten by the ID children. Pupils spent most of their time engaging in low levels of activity such as reading, watching TV, on games consoles and listening to music. Pupils with an ID diagnosis also spent fewer hours on moderate and high levels of activities compared with those children with no ID. Intervention here thus appears very crucial especially for more modestly affected ID youth because another report shows greater obesity prevalence occurs among those with ID who are able to eat, shop, and prepare meals independently [32].

Since relatively speaking, very little attention has been forthcoming to resolving this health threat of overweight among ID children, if we compare publication numbers to those in the mainstream, as urged by Grondhuis & Aman [4] and De Winter et al. [32] what data do exist clearly demonstrate that it is in the best interest of this group of challenged youth to begin to seriously eliminate this potential life-long health burden and its negative ramifications.

Since the ID problem is usually the issue of most concern to parents, in addition to identifying and intervening on childhood obesity determinants in this population [10], elevating the profile of this issue among parents and caregivers, as well as pediatricians, school personnel, and harm reduction experts using the most promising approaches [17] is crucial. As well, concerted carefully construed educational efforts about this issue may reduce the additional social stigma and isolation associated with being an overweight child.

Education concerning the fact that individuals with ID who are less physically active, have more sedentary lives, and lower fitness levels, are more likely to be overweight or obese with poorer health outcomes [26,33] and that physical activity is not a choice but a necessity, is of utmost import in this respect. In addition, as per findings of Hoey et al. [34], where adults with ID ages 1664 continued to show mean energy intakes from sugar, fat and saturated fat higher than those recommended and that few met micronutrient recommended daily amounts, while displaying a high prevalence of overweight and obesity, it appears crucial to educate and promote healthy feeding practices in this at risk group of children [35]. Gawlik et al. [36] too who studied adults with ID further revealed that their study group was characterized not only by excess body mass, but by insufficient levels of physical activity, hence emphasizing the urgent 'call to action' in this sphere that has prevailed since 2014 [4] and affects an alarmingly high proportion of this growing adult population [7].

References

- Collins K, Staples K (2017) The role of physical activity in improving physical fitness in children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 69: 49-60.

- Marti'nez-Leal R, Salvador-Carulla L, Gutierrez-Colosi'a MR, Nadal M, Novell-Alsina R, et al. (2011) Health among persons with intellectual disability in Spain: the European POMONA-II study. Rev Neurol 53(7): 406-414.

- Smyth P, McDowell C, Leslie JC, Leader G, Donnelly M, et al. (2017) Managing weight: what do people with an intellectual disability want from mobile technology? Stud Health Technol Inform 242: 273-278.

- Grondhuis SN, Aman MG (2014) Overweight and obesity in youth with developmental disabilities: a call to action. J Intellect Disabil Res 58(9): 787-799.

- Basil JS, Santoro SL, Martin LJ, Healy KW, Chini BA, et al. (2016) Retrospective study of obesity in children with Down Syndrome. J Pediatr 173: 143-148.

- Charlot L, Abend S, Ravin P, Mastis K, Hunt A, et al. (2011) Nonpsychiatric health problems among psychiatric inpatients with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 55(2): 199-209.

- Ranjan S, Nasser JA, Fisher K (2017) Prevalence and potential factors associated with overweight and obesity status in adults with intellectual developmental disorders. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil.

- Emerson E, Robertson J, Baines S, Hatton C (2016) Obesity in British children with and without intellectual disability: cohort study. BMC Public Health 16: 644.

- Bandini L, Danielson M, Esposito LE, Foley JT, Fox MH, et al. (2015) Obesity in children with developmental and/or physical disabilities. Disabil Health J 8(3): 309-316.

- Peterson JJ, Janz KF, Lowe JB (2008) Physical activity among adults with intellectual disabilities living in community settings. Prev Med 47(1): 101-106.

- Heller T, Sorensen A (2013) Promoting healthy aging in adults with developmental disabilities. Dev Disabil Res Rev 18(1): 22-30.

- Dunkley AJ, Tyrer F, Gray LJ, Bhaumik S, Spong R, et al. (2017) Type 2 diabetes and glucose intolerance in a population with intellectual disabilities: the STOP diabetes cross-sectional screening study. J Intellect Disabil Res 61(7): 668-681.

- Pan CC, Davis R, Nichols D, Hwang SH, Hsieh K (2016) Prevalence of overweight and obesity among students with intellectual disabilities in Taiwan: a secondary analysis. Res Dev Disabil 53-54: 305-513.

- Franke ML, Heinrich M, Adam M, Sunkel U, Diefenbacher A, et al. (2017) Body weight and mental disorders: results from a clinical psychiatric cross-sectional study of people with intellectual disabilities. Nervenarzt.

- Bertapelli F, Pitetti K, Agiovlasitis S, Guerra G (2016) Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with Down syndrome-prevalence, determinants, consequences, and interventions: a literature review. Res Dev Disabil 57: 181-92.

- Lee RL, Leung C, Chen H, Louie LHT, Brown M, et al. (2017) The impact of a school-based weight management program involving parents via mhealth for overweight and obese children and adolescents with intellectual disability: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(10): E1178.

- Voll SL, Boot E, Butcher NJ, Cooper S, Heung T, et al. (2017) Obesity in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Genet Med 19(2): 204-208.

- Savage A, Emerson E (2016) Overweight and obesity among children at risk of intellectual disability in 20 low and middle income countries. J Intellect Disabil Res 60(11): 1128-1135.

- Bennett EA, Kolko RP, Chia L, Elliott JP, Kalarchian MA (2017) Treatment of obesity among youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities: an emerging role for telenursing. West J Nurs Res 39(8): 1008-1027.

- Marti'nez-Zaragoza F, Campillo-Marti'nez J, Ato-Garci'a M (2016) Effects on physical health of a multicomponent programme for overweight and obesity for adults with intellectual disabilities. J Applied Res Intellectual Disabil 29(3): 250-265.

- Lobenius-Palmer K, Sjoqvist B, Hurtig-Wennlof A, Lundqvist LO (2017) Accelerometer-assessed physical activity and sedentary time in youth with disabilities. Adapt Phys Activ Q 26: 1-19.

- Ptomey LT, Saunders RR, Saunders M, Washburn RA, Mayo MS, et al. (2017) Weight management in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a randomized controlled trial of two dietary approaches. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil.

- Hinckson E, Dickinson A, Water T, Sands M, Penman L (2013) Physical activity, dietary habits and overall health in overweight and obese children and youth with intellectual disability or autism. Res in Dev Disabil 34(4): 1170-1178.

- < Wu W, Yang Y, Chu I, Hsu H, Tsai F, Liang J (2017) Effectiveness of a crosscircuit exercise training program in improving the fitness of overweight or obese adolescents with intellectual disability enrolled in special education schools. Res Dev Disabil 60: 83-95.

- Chang C, Chang M, Shih C (2016) Encouraging overweight students with intellectual disability to actively perform walking activity using an air mouse combined with preferred stimulation. Res Dev Disabil 55: 37-43.

- Peterson JJ, Lowe JB, Peterson NA, Nothwehr FK, Janz KF, et al. (2008) Paths to leisure physical activity among adults with intellectual disabilities: self-efficacy and social support. Am J Health Promot 23(1): 35-42.

- Podgorska-Bednarz J, Rykaia J, Mazur A (2015) The risk factors of overweight and obesity in children with intellectual disability from South-East of Poland. Appetite 89: 327.

- Mikulovic J, Marcellini A, Bui-Xuan G, Duchateau G, Vanhelst J et al. (2011) Prevalence of overweight in adolescents with intellectual deficiency. Differences in socio-educative context, physical activity and dietary habits. Appetite 56(2): 403-407.

- Choi E, Park H, Ha Y, Hwang WJ (2012) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in children with intellectual disabilities in Korea. J App Res in Intellectual Disabil 25(5): 476-483.

- Maiano C (2011) Prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Obesity Rev 12(3): 189-197.

- Slevin E, Truesdale-Kennedy M, McConkey R, Livingstone B, Fleming P (2014) Obesity and overweight in intellectual and non-intellectually disabled children. J Intellectual Disabil Res 58(3): 211-220.

- de Winter C, Bastiaanse L, Hilgenkamp T, Evenhuis H, Echteld M (2012) Overweight and obesity in older people with intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil 33(2): 398-405.

- Walsh D, Belton S, Meegan S, Bowers K, Corby D, et al. (2017) A comparison of physical activity, physical fitness levels, BMI and blood pressure of adults with intellectual disability, who do and do not take part in Special Olympics Ireland programmes. J Intellect Disabil Jan 1: 1744629516688773.

- Hoey E, Staines A, Sweeney M, Corby D, Bowers K et al. (2017) An examination of the nutritional intake and anthropometric status of individuals with intellectual disabilities: results from the SOPHIE study. J Intellectual Disabil 21(4): 346-365.

- Polfuss M, Simpson P, Neff Greenley R, Zhang L, Sawin KJ (2017) Parental feeding behaviors and weight-related concerns in children with special needs. West J Nurs Res 39(8): 1070-1093.

- Gawlik K, Zwierzchowska A, Celebanska D (2017) Impact of physical activity on obesity and lipid profile of adults with intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil.

© 2017 Ray Marks. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)