- Submissions

Full Text

Developments in Anaesthetics & Pain Management

Posterior Lumbar Plexus Block for Postoperative Analgesia in Elderly Orthopedic Surgery Study in 160 Patients

Luiz Eduardo Imbelloni1*, Douglas MP Teixeira2, Umberto Lima2, Thaís Bezerra Ventura3, Siddharta Lacerda4, Bruno Brasileiro5, Robson Barbosa6, Micaela Barbosa L7, Márcio Duarte8 and Geraldo Borges de Morais Filho9

1Anesthesiologist of Complexo Hospitalar Mangabeira, Brazil

2Orthopedic Surgeon of Complexo Hospitalar Mangabeira Gov. Tarcisio Burity, Brazil

3Anesthesiologist of Hospital Regional Wenceslaw Lopes, Brazil

4Anesthesiologist of Hospital da Santa Clara, Brazil

5Anesthesiologist of Hospital Alberto Urquiza Wanderley, Brazil

6Anesthesiologist of Hospital Regional do Agreste, Brazil

7Anesthesiology of Hospital Dom Helder, Brazil

8Anesthesiologist of Hospital Polícia Militar General Edson Ramalho, Brazil

9Master in Labour Economics, UFPB, Barzil

*Corresponding author: Luiz Eduardo Imbelloni, Anesthesiologist of Complexo Hospitalar Mangabeira, Brazil

Submission:May 09, 2022;Published: May 19, 2022

ISSN: 2640-9399 Volume2 Issue3

Abstract

Background: A posterior lumbar plexus block or psoas compartment block is an effective locoregional

anesthetic technique for anesthesia and analgesia. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of

a single injection of 40ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine (S75:R25) through neurostimulator-assisted psoas

compartment block for postoperative analgesia in elderly patients undergoing femur surgery in lateral

recumbency.

Methods: One hundred and sixty elderly patients with a femur fracture received a lumbar plexus block in

the psoas compartment at the end of the surgery, still under the effect of spinal anesthesia, and pain was

evaluated six hours after the injection and 24 hours after the blockade. The need for rescue with opioids

and the complications of the block were evaluated.

Results: Evaluation of the five nerves showed that they were all blocked in all patients at the six-hour

post-injection evaluation. In the evaluation performed 24 hours later, only 40 patients (25%) had all

five nerves blocked. The mean time to perform the block and local anesthetic injection was 3:00±0:36

minutes. The mean duration of analgesia was 24:16±3:98 hours, with a minimum value of 16 hours and a

maximum of 34 hours. The lock has reduced the amount of postoperative opioids and only three patients

required additional analgesic. No complications were reported in any patients.

Conclusion: Posterior lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment) has been shown to be effective for

both anesthesia and analgesia after femoral fracture surgery. The lumbar plexus block decreases opioid

consumption, enhances patient comfort, and promotes postoperative ambulation and physical therapy.

It can play a pivotal role in enhanced recovery programs for hip surgery, applied to elderly patients with

femoral fractures in a hospital of the Brazilian Health System (SUS).

Keywords: Electric nerve stimulation; Psoas compartment block; Levopubivacaine; Complications; Femur fracture

Introduction

Posterior lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment) is a deep block, considered an advanced technique of regional anesthesia that should only be performed by physicians experienced in these approaches. Lumbar plexus block, both inguinal and psoas compartment, are powerful tools for postoperative pain control, reducing postoperative opioid consumption [1,2]. In 1976, posterior lumbar plexus access or psoas compartment access was described, which proved to be a more reliable technique for blocking the entire lumbar plexus with a single injection [3]. The first description of the approach to the lumbar plexus in the psoas compartment was performed with loss of resistance, later with neurostimulator and finally with ultrasound. In a recent study comparing various techniques for locating the posterior lumbar plexus such as Loss of Resistance (LOR), Electrical Nerve Stimulation (ENS), Ultrasound- Guided Approach (US) and combined ultrasound-guided and Electrical Nerve Stimulation (US/ENS), in 140 patients (35 of each), showed that usage of combined ultrasound and electric nerve stimulation was better regarding the outcome and complications [4]. In another study, 300 patients undergoing elective lower limb surgery with lumbar plexus blocks and sciatic nerve blocks were randomly assigned to receive the blocks addressed with ultrasound, nerve stimulator, or dual guidance [5]. The primary end point was the incidence of local anesthetics systemic toxicity (LAST) and the secondary end points were the number of needle redirection, motor and onset of sensory block and time to restoration of nerve distribution, as well as associated risk factors. The result showed that the ultrasound guidance, hepatitis B infection and the female sex were risk factors of LAST with both blocks. For patients infected with hepatitis B or female patients receiving lumbar plexus block and sciatic block, it was recommended that combinedultrasound and nerve stimulator guidance should be used to improve the safety.

In a study aimed at evaluating the efficacy of a single injection of 40ml of 0.25% bupivacaine in the lumbar plexus block in the psoas compartment with a neurostimulator in orthopedic surgery, showed that the ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, lateral cutaneous of the thigh, femoral and obturator were blocked in 90% of patients [6]. Blockage has reduced the amount of postoperative opioids, and 52.5% of patients required no additional postoperative analgesia, with analgesia duration of approximately 24 hours, with no local anesthetic intoxication or complications of the posterior lumbar plexus approach. Complications related to lumbar plexus block in the psoas compartment are rare. Although there are authors who report a high incidence of dissemination of the local anesthetic to the epidural space [7,8], our experience in more than 30 years of plexus access with neurostimulator is quite the opposite. In the view of postoperative patients, the priority of care should be given to the measurement of pain intensity and analgesia assessment, being one of the main components of patient satisfaction in the immediate and late postoperative period and their relief is a human right [9]. In addition, the American Pain Society proposes that patient satisfaction with the analgesia received during hospitalization be an indicator of the institution’s quality [10].

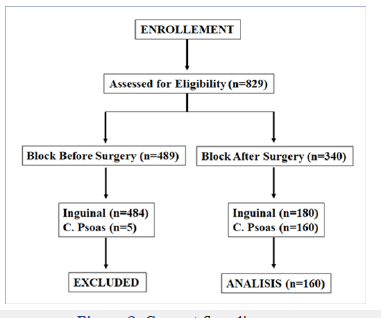

A study was recently published with 829 elderly patients undergoing orthopedic hip surgery, which was performed for postoperative analgesia, before surgery, 489 neurostimulator blocks were performed (484 inguinal and 5 psoas) and 340 after the end of surgery (180 inguinal and 160 psoas) [11]. The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of analgesia by applying a single levobupivacaine (S75:R25) injection into the psoas compartment, the possible complications, the dispersion of the local anesthetic and the possibility of an epidural, using a peripheral nerves stimulator in hip and femur orthopedic surgeries.

Methods

The prospective study was carried out during ten years, with all patients who underwent corrective operations for femur fractures aged over 60 years. The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Number 171,924) and registered on Plataforma Brasil (CAAE: 09061312.1.0000.5179) and all patients were informed and agreed to participate in the program and signed the free and informed consent form. During the pre-anesthetic visit the project was detailed explained to the patient and family. All elderly patients with a femoral fracture who were admitted to the Complexo Hospitalar Mangabeira of the Brazilian Health System (CHM-SUS) and all patients normovolemic, without neurological disease, without coagulation disorders, without infection at the lumbar puncture site L2-L3, L3-L4, who did not present agitation and/or delirium, did not use an indwelling urinary catheter, with a hemoglobin level > 10g %, who were anesthetized under spinal anesthesia without opioids and lumbosacral plexus block for analgesia and who were not admitted to the ICU, were included in the Excel spreadsheet for further study. All orthopedists were trained and at the beginning of the project there were no residents in orthopedics.

Patients included in the study received food the day before the operation, 200mL of maltodextrin 2 to 4 hours before being referred to the Operating Room (OR). The surgeries would be performed until 2pm and they would remain in the post-anesthetic recovery room (PACU) until the end of the block, when they were again given 200mL of maltodextrin. After 30 to 60 minutes, if the patients accepted oral feeding without nausea or vomiting, they were referred to the ward, without intravenous hydration and with free diet released in the ward. remained with a venous catheter saline for injection of antibiotics, analgesics and other intravenous medications.

All patients received a standardized spinal anesthesia. No preanesthetic medication was administered while in the bedroom. After venoclysis with 18G or 20G catheter, infusion was initiated with Ringer lactate solution, in parallel with 6% hydroethyl starch. Monitoring at operating theater was provided by continuous ECG at CM5, blood pressure by non-invasive method, as well as pulse oxymetry. In no patient bladder catheterization was used. After sedation with intravenous dextroketamine (0.1mg/kg) and midazolam (0.5 to 1mg) and skin cleansing with alcoholic chlorhexidine, spinal puncture was performed with the patient in the sitting position, through the median route in the interspaces L2- L3 or L3-L4, using 25G, 26G or 27G needle type Quincke without introducer. After the appearance of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) confirming the correct position of the needle, 6 to 15mg of isobaric 0.5% bupivacaine were administered at a rate of 1mL/15s.

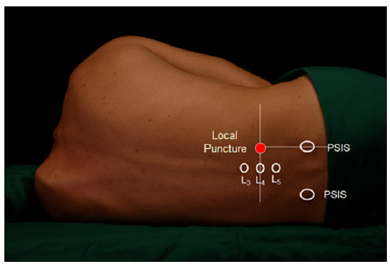

At the end of the surgery, all patients operated on in lateral decubitus were selected to receive a lumbar plexus block in the psoas compartment with the aid of a neurostimulator, for postoperative analgesia. Lumbar plexus blockage at psoas compartment (Figure 1) was made with the patient lying at lateral position with the operated limb pointing up at the end of surgery, with 10mm needle (B.Braun Melsungen AG, 21G 0.8x100mm needle) connected to a peripheral nerve stimulator (HNS 12 Stimuplex®, B.BraunMelsungen AG) adjusted to release 1mA, 1Hz squared pulsed current, perpendicularly inserted approximately 5-8cm deep, aiming to achieve femoral quadriceps muscle contraction. When contraction was achieved, the current was reduced to 0.5mA, and, if the contractile response remained, 40ml 0.25% levobupivacaine (S75:R25) was injected after negative aspiration for blood. The time from puncture with ENS and A100 needle to complete injection of 40ml of local anesthetic was evaluated, with an appropriate timer. In some patients, 20ml of iohexol dye with 300mg/ml were injected in order to study local anesthetic agent dispersion. The CHM did not have an ultrasound device for performing peripheral nerve blocks. After injection at the anesthetic site, patients were placed in the supine position and monitored for 30 minutes to assess possible complications, such as venous injection, epidural dispersion, or injection into the kidney. After this period, the patient was transferred to the PACU, remained monitored and was only discharged to the ward after the end of the spinal anesthesia block, and ingestion of 200ml maltodextrin.

Figure 1:Lumbar plexus block via the psoas compartment. (PSIS=Posterior Superior Iliac Spine).

Analgesia was assessed by the resident anesthesiologist by means of needle-puncture and cold test in order to determine the extension of sensitive blockage on ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, lateral cutaneous of the femur, obturator and femoral 6 hours to confirm blockage effectiveness and 24 hours after anesthetic injection [6], and the moment of the first pain complaint was recorded for patients not receiving additional analgesics. Patients were transferred to the room without venous hydration, with a saline venous catheter and received dipyrone 1g 6/6h and cefazolin 1g 6/6h. The patients were followed-up for 24 hours for checking the presence of complications at the blockage site, as well as for identifying blood hypotension as a potential single-or bilateral epidural blockage. The patient was followed up at home by telephone by the anesthetic team.

Statistical analysis

The results were assessed by the descriptive analysis of then studied variables and, whenever applicable, by mean and standard deviation values.

Result

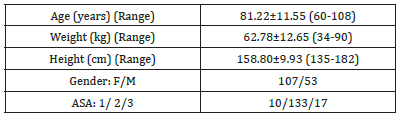

One hundred and sixty patients of both sexes, with femur fracture in elderly patients over 60 years old, received lumbar plexus block via psoas compartment with neurostimulator for postoperative analgesia at the end of surgery, according to the consort flow diagram (Figure 2). One hundred and seven women (66.87%) and 53 (33.13%) men patients underwent differtent types of surgical correction of femur, operated in lateral decubitus, participated in the study. The mean age of the 160 patients was 81.22±11.55 years, the mean weight was 62.78±12.65kg and the mean height was 158.80±9.93cm. Demographic data of patients are shown in Table 1. One hundred and sixty patients who received lumbar plexus block via the psoas compartment for postoperative analgesia at the end of elderly orthopedic femur surgery with nerve stimulator, showing a satisfactory quality of analgesia with a mean duration of analgesia of 24 hours no side effects. The mean time to access the posterior lumbar plexus with ENS was 3:00±0:36 minutes, ranging from 1:45 to 4:30 minutes.

Figure 2:Consort flow diagram.

Table 1:Demografics dates of patients.

All five nerves were blocked (full sensitive blockage of the ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, lateral cutaneous of the femur,obturator, and femoral nerves) in all 160 (100%) patients, 6 hours after performing the psoas block. The evaluation of the five nerves 24 hours after the injection of the levobupivacaine (S75:R25) 0.25% showed that 40 patients (25%) five blocked nerves, 8 patients (5%) had four blocked nerves, 48 patients (30%) had three blocked nerves, 32 patients (20%) had two blocked nerves, and 32 pacients (20%) only one blocked nerve. However, only three patients required additional analgesic. Surgical time was 2:05±0:35 hours and duration of spinal anesthesia was 3:01±0:36 hours. The average dose of 0.5% isobaric bupivacaine was 10.22±1.88mg, with the lowest dose used being 6mg and the highest dose being 15mg. The cephalad dispersion varied between T12 and T7, in all patients, and the mode was the same T11 regardless of age group of patients. All patients had complete motor block.

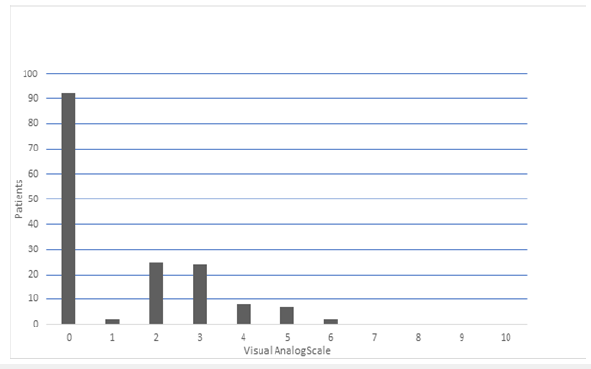

In all patients, the first evaluation (6 hours after psoas compartment blockage) was conducted without any residual blockage of the spinal anesthesia. The mean duration of analgesia was 24:16±3:98 hours, with a minimum value of 16 hours and a maximum of 34 hours. The anesthetic agent dispersion immediately after injection evidenced head and tail dispersion (Figure 3). Pain assessment 24 hours after lumbar block in the psoas compartment, showed that 57.5% of patients did not report any pain (Figure 4). Likewise, there was no motor block in the operated limb. No complication at puncture site was seen throughout follow up time. Neither vascular injection nor unplanned puncture has occurred on subarachnoid space or epidural space, followed for the first six hours. No bradycardia or blood hypotension events were seen in the first 24 postoperative hours. No neurological complication was reported. No patient required vesicle catheterization, and no patient was referred to the ICU. No patient complained of paresthesia after 48 hours of follow-up. All patients were able to be referred to their residence, depending on the Hospital’s Social Service.

Figure 3:Dispersion of local anesthetic associated with contrast after 2 minutes of injection in psoas compartment.

Figure 4:Pain assessment 24 hours after lumbar block in the psoas compartment.

Discussion

Posterior lumbar plexus block (in the psoas compartment) with the aid of a peripheral nerve stimulator is a deep approach, technically safe, easy and without adverse effects in 160 patients performed by a professional with experience in the technique. This access route to the lumbar plexus resulted in a block of five nerves in all patients (100%), evaluated at six hours after the block. Evaluation of the five nerves 24 hours after injection showed blockage in 40 patients (25%), resulting in no pain in 57.5% of patients. Similar result in another study with the same technique in 40 orthopedic surgery patients [6]. The upper leg segment is basically innervated by lumbar in the anterior region and sacral plexus in the posterior region. The lumbar plexus is formed within the body of the psoas muscle by the four spinal nerves of L1 to L4: iliohypogastric nerve is formed by T12 and L1, ilioinguinal nerve is formed by L1, genitofemoral nerve is formed mainly by L1-L2, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is formed by the posterior division of L2 and L3, femoral nerve is formed by the posterior division of L2, L3, L4, and obturator nerve is formed by the former division of L2, L3, L4 [12].

Lumbar plexus blockage at psoas compartment should be performed with the patient at lateral position with the operated limb up, with a 100-150mm needle perpendicular to skin plane, at usual depth 8cm [12]. In this study, we used the plexus stimulator with a 100mm needle, having achieved lumbar plexus with quadriceps contraction in all patients. The lumbar plexus stimulation was used in lateral decubitus with patients still under spinal anesthesia effect. Due to the presence of residual spinal anesthesia, it was not possible to assess whether the use of a neurostimulator is uncomfortable for accessing the lumbar plexus within the psoas muscle. In this study with 240 patients, no nerve damage was noted, and no patient had a hematoma after puncture with an A100 needle. The combined use of US and ENS provided a better result than the individual application of US or ENS, as well as the loss of resistance for locating the lumbar plexus within the psoas [4]. Likewise, the incidence of complications was very low [4]. Regarding analgesic efficacy, there is substantial evidence that the posterior approach to the lumbar plexus (psoas compartment) has significant advantages compared to the anterior approach to the lumbar plexus (inguinal approach). The posterior lumbar plexus block is superior to the anterior paravascular plexus approach, blocking virtually all branches of the plexus unlike the “3 in 1” block described by Winnie [13]. The posterior approach is more effective in the blockade of the five nerves of the lumbar plexus [6]. In this study with 160 patients, the five nerves were blocked in all patients in the evaluation six hours after the puncture, and in 40 patients (25%) in the evaluation 24 hours later.

In any regional anesthesia technique, psoas compartment block can have undesirable side effects. Several complications have already been described in different case reports, some of which are seriously life-threatening. In our study, none of the eight complications reported in these two articles were observed [8,14]. The use of US with ENS to approach the posterior lumbar plexus (psoas compartment) in lateral decubitus results in a statistically shorter total time to perform the block (mean 7.4 minutes) compared to US alone [15]. In this study, because the CHM does not have US, all blocks were performed only with ENS, and the average time was three minutes. In a recent study evaluating the dose of 0.5% ropivacaine to be successful in 95% of patients with posterior lumbar plexus block was 36ml [16]. Enantiomeric excess bupivacaine (S75:R25) is a local anesthetic derived from bupivacaine developed in Brazil during the last two decades of the 20th Century [17,18]. In two studies, 40ml of 0.25 enatiomeric mixture (S75:R25) for bilateral pudendal nerve block with neurostimulator provided excellent analgesia, with low need for opioids, without systemic or local complications, without urinary retention, with residual analgesia for more than 24 hours and first defecation without pain, and high level of satisfaction [19,20]. In elderly patients with femoral fractures and the same dose of enantiomeric mixture through lumbar plexus block, analgesia ranged from 14 to 33 hours, with a mean of 22 hours. In several articles published in Brazil with the enantiomeric mixture of bupivacaine (S75:R25), in 454 patients who underwent epidural, brachial or lumbar plexus block, postoperative analgesia by bilateral pudendal nerve block, there is no report of toxicity with cardiac arrest [18]. The anesthetic agent dispersion with contrast after two minutes of injection evidenced head and tail dispersion.

Conclusion

Posterior lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment) has been shown to be effective for both anesthesia and analgesia after femoral fracture surgery. Its analgesic potency is similar to that provided by epidural anesthesia, for femur fracture without undesirable side effects. The lumbar plexus block decreases opioid consumption, enhances patient comfort, and promotes postoperative ambulation and physical therapy. It can play a pivotal role in enhanced recovery programs for hip surgery, applied to elderly patients with femoral fractures in a hospital of the Brazilian Health System (SUS). Knowledge of the anatomy of the lumbar plexus, the different techniques of the block, its indications and contraindications are considered essential for the practice of this technique, mainly aided by US or ENS, leaving aside approaches due to loss of resistance.

References

- Imbelloni LE, Teixeira DMP, Coelho TM, Gomes D, Braga RL, et al. (2014) Implementation of a perioperative management protocol for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery. Rev Col Bras Cir 41(3): 161-167.

- Imbelloni LE, Morais Filho GB (2016) Attitudes, awareness and barriers regarding evidence-based orthopedic surgery between health professionals from a Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) hospital: Study of 400 patients. Anesth Essays Res 10(3): 546-551.

- Chayen D, Nathan H, Chayen M (1976) The psoas compartment block. Anesthesiology 5(1): 9-99.

- Awadalla AMM, Botros AR, Ellatif HKA (2021) Psoas compartment block for lower limb surgeries: A comparative study among the four lumbar plexus localizing methods. The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine 84(1): 1772-1781.

- Zhang XH, Li YJ, He WQ, Yong CY, Teng Gu J, et al. (2019) Combined ultrasound and nerve stimulator-guided deep nerve block may decrease the rate of local anesthetics systemic toxicity: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiology 19(1): 103.

- Imbelloni LE (2008) Lumbar plexus blockage on psoas compartment for postoperative analgesia after orthopaedic surgeries. Acta Ortop Bras 16(3): 157-160.

- Capdevila X, Coimbra C, Choquet O (2005) Approaches to the lumbar plexus: Success, risks, and outcome. Reg Anesth Pain Med 30(2): 150-162.

- De Leeuw MA, Zuurmond WWA, Perez RSMG (2011) The psoas compartment block for hip surgery: The past, present, and future. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2011: 159541.

- Iuppen LS, Sampaio FH, Stadñik CMB (2011) Patients’ satisfaction with the implementation of the concept of pain as the fifth vital sign to control postoperative pain. Rev Dor São Paulo 12(1): 29-34.

- Miaskowski C, Nichols R, Brody R, Synold T (1994) Assessment of patient satisfaction utilizing the American Pain Society's Quality Assurance Standards on acute and cancer-related pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 9(1): 5-11.

- Imbelloni LE, Teixeira DMP, Lima U (2022) Accelerated operative recovery in elderly patients with femoral fractures. Experience for ten years with 870 patients. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care.

- Farny J, Drolet P, Girard M (1994) Anatomy of the posterior approach to the lumbar plexus block. Can J Anaesth 41(6): 480-485.

- Touray ST, De Leeuw MA, Zuurmond WWA, Perez RSGM (2008) Psoas compartment block for lower extremity surgery: A meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 101(6): 750-760.

- Mannion S (2007) Psoas compartment block. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care and Pain 7(5): 162-166.

- Arnuntasupakul V, Chalachewa T, Leurcharusmee P, Andersen MN, Daugaard M, et al. (2018) Ultrasound with neurostimulation compared with ultrasound guidance alone for lumbar plexus block: a randomised single blinded equivalence trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 35(3): 224-230.

- Sauter AR, Ullensvang K, Niemi G, Lorentzen HT, Bendtsen TH, et al. (2015) The shamrock lumbar plexus block. A dose finding study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 32(11): 764-770.

- Imbelloni LE, Araujo AA, Sakamoto JW, Viana EP (2020) Levobupivacaine hydrochloride in 50% enantiomeric excess (S75:R25). A new local anesthetic safer alternative. Review Article. World J Pharm Pharm Scien 9(5): 1804-1819.

- Imbelloni LE (2021) Enantiomeric excess of bupivacaine (S75:R25): Laboratory study, clinical application and toxicity. J Clin Anesthesiol 5(4): 116.

- Imbelloni LE, Beato L, Beato C, Cordeiro JA, De Souza DD (2005) Bilateral pudendal nerves block for postoperative analgesia with 0.25% S75:R25 bupivacaine: Pilot study on outpatient hemorrhoidectomy. Rev Bras Anesthesiol 55(6): 614-621.

- Imbelloni LE, Vieira EM, Carneiro AF (2012) Postoperative analgesia for hemorrhoidectomy with bilateral pudendal blockade on an ambulatory patient: A controlled clinical study. J Coloproctol 32(3): 291-296.

© 2022 Luiz Eduardo Imbelloni. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)