- Submissions

Full Text

Developments in Anaesthetics & Pain Management

Echinocandin in an Intensive Care Unit: A Pearl’s Peril in Intra Abdominal Post-Operative Care

Alexandra E Lee1 and Vikram Anumakonda2*

1 Senior Honorary Clinical Lecturer, University of Birmingham, UK

2 Consultant Physician, Critical Care Medicine, UK

*Corresponding author: Vikram Anumakonda, Consultant Physician, Critical Care Medicine, Consultant Physician, Critical Care Medicine, Pensnett Road, Dudley DY1 2HQ

Submission: December 18, 2017;Published: July 19, 2018

ISSN: 2640-9399 Volume1 Issue4

Abstract

Anidulafungin is an echinocandin armamentarium antifungal drug, indicated for use in invasive candidiasis [1]. The mechanism of action is by preventing the synthesis of fungal cell walls [2], However identification and initiation of treatment for invasive candidiasis is difficult and challenging for intensivists in a cohort of critically ill patients during post-operative period. To our knowledge this is the first documented case of such side effects associated with the use of Anidulafungin.

Introduction

During post-operative period, identification of fungal infection is challenging to diagnose. Most of the patients have multiple drains inserted during surgical procedures to facilitate drainage end up staying in-situ due to on-going risk of persisting intra-abdominal collection or fistula. In some elderly patients, surgeon prefer them to be left if the output from drain remains high as risk of opening abdomen is deemed far higher. In all these cases, despite use of biomarkers like pro calcitonin and other investigations, it is down to clinicians to rule out fungal infections in acute setting mainly using his clinical acumen.

Anidulafungin is an Echinocandin antifungal drug, indicated for use in invasive candidiasis [1]. The mechanism of action is via the inhibition of beta-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase thereby, preventing the synthesis of fungal cell walls [2].

Case Summary

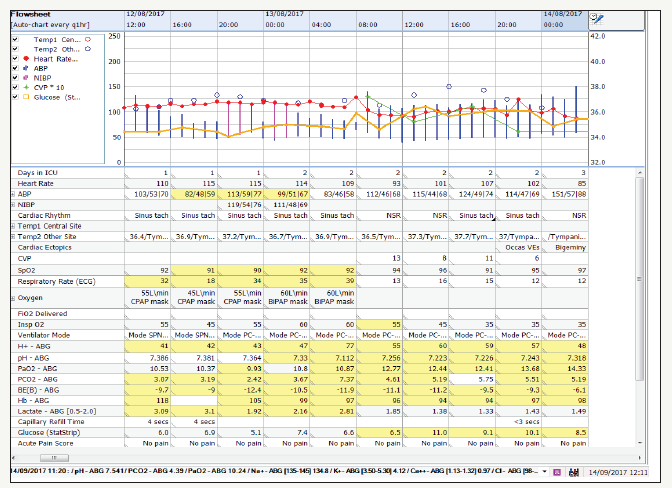

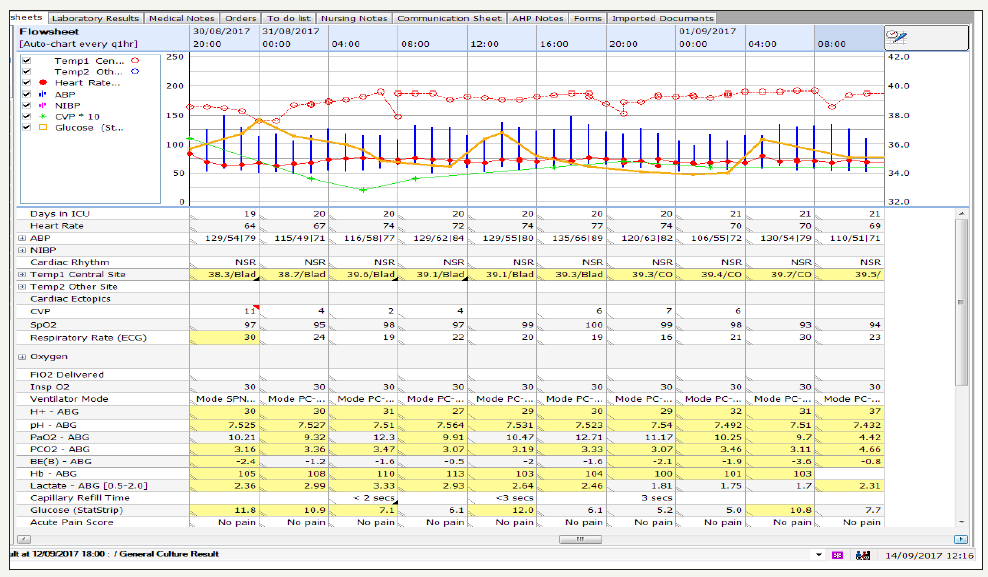

figure 1: Flow sheet of the patient’s daily vital observations, ventilation mode and arterial blood gas analysis etc demonstrating type1 respiratory failure with increasing FiO2 requirements on ITU.

A 58 years old lady presented to A&E with sudden onset, epigastric pain, associated with an episode of vomiting a few hours later. Her past medical history included hypertension and breast cancer, for which she underwent a lumpectomy. In addition, her regular medications included bendroflumethiazide, exemstone and loratadine. On examination, the patient was tachycardic with a rigid abdomen and generalised tenderness [3-5]. Both Cullen’s and Grey Turner’s signs were negative. Initial investigations revealed a serum amylase of 1400U/l, a lactate of 6.4(units) and CT scan revealed severe interstitial pancreatitis of unknown aetiology. She was admitted to the surgical high dependency unit, where triple antibiotic therapy (metronidazole, gentamicin and meropenem), fluid resuscitation and non-invasive ventilation were commenced (Figure 1).

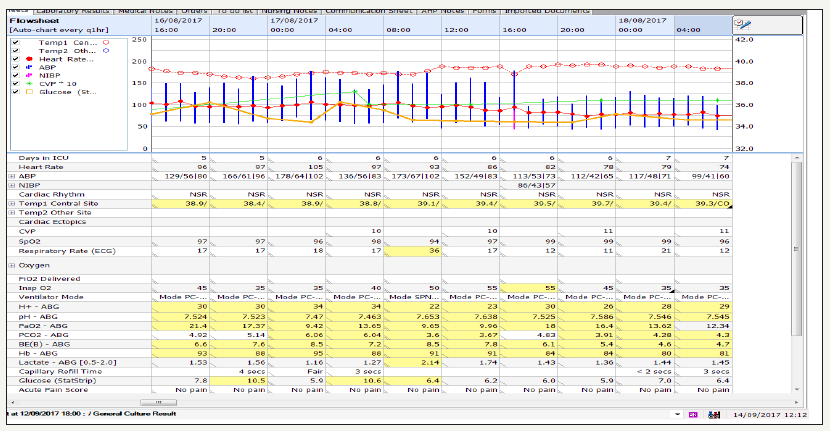

On day 3, the patient was admitted to ICU in view of a rising creatinine, procalcitonin and respiratory failure needing NIV. She had type 6 loose stool, a temperature of 36.4°c and was continued on the same antibiotic regime (Figure 2 & 3).

figure 2: Flow sheet of the patient’s daily vital observations, ventilation mode and arterial blood gas analysis etc, demonstrates persistent rise in her body temperatures (pyrexia).

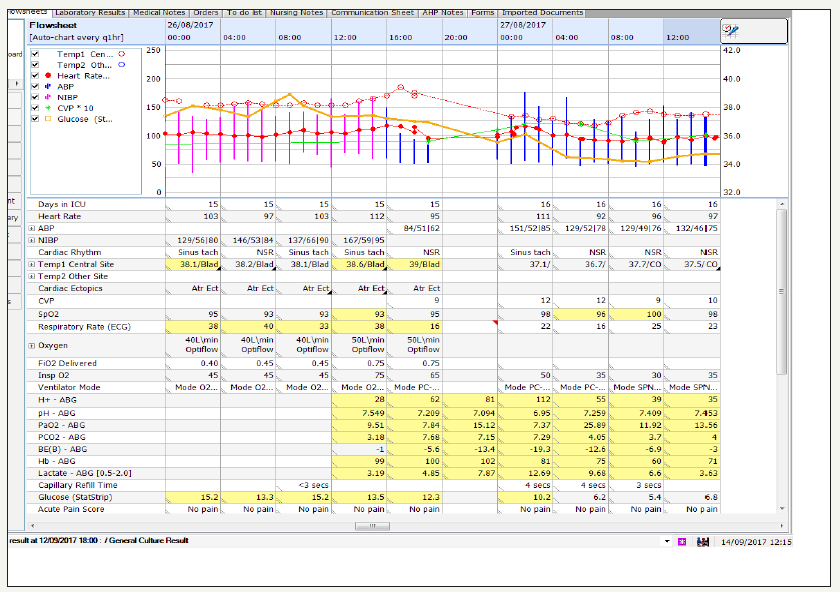

figure 3: Flow sheet of the patient’s daily vital observations, ventilation mode and arterial blood gas analysis etc. demonstrates patient struggling with opt flow (High flow) oxygen after successful extubating heading to re-intubation and invasive ventilation. It also demonstrates incremental trends in glucose signalling complete loss of functioning beta cells of Pancreas.

On day 7, the patient deteriorated further, becoming pyrexic and requiring intubation due to respiratory failure. An anti-fungal, fluconazole, was commenced in addition to the antibiotics. Over the course of the next week, the patient showed improvement in `inflammatory markers and was extubated, however, she remained pyrexic (Figure 4-7).

figure 4: Flow sheet demonstrating persistent high grade pyrexia despite fluconazole and antimicrobial regime.

figure 5:Flow sheet demonstrates the patient’s septic showers.

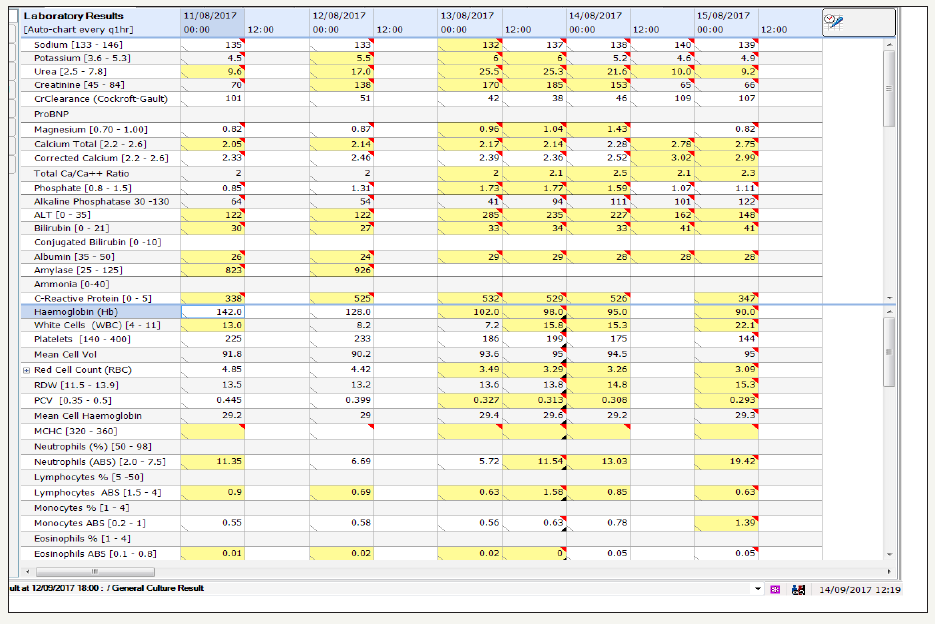

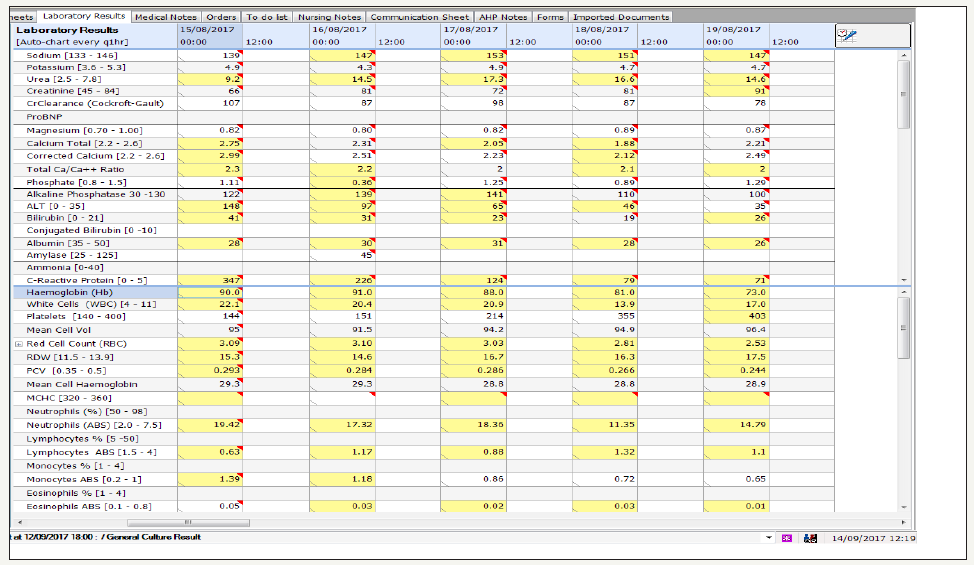

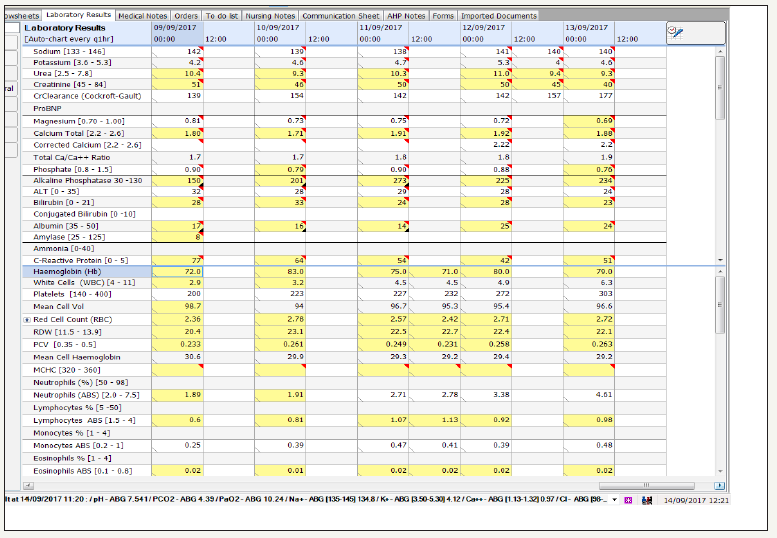

figure 6: Flow sheet of the patient’s c-reactive protein, biochemistry and complete blood count reflecting septic process despite antimicrobial.

figure 7: Flow sheet of the patient’s white cell lineage trending after starting Andilufungin

On day 18 the patient acutely deteriorated with an increased work of breathing followed by a drop in blood pressure. She had a semi-elective reintubation in view of her clinical deterioration and impending respiratory failure due to septic showers. A Computer tomography imaging revealed a perforated large bowel secondary to necrotizing pancreatitis requiring an emergency laparotomy with sub-total colectomy [6-8].

Fourth day post operatively, gentamicin was switched to vancomycin after staphylococcus epidermidis was grown from the abdominal drain fluid. However, patient remained pyrexic and spiked high temperatures all throughout [9].

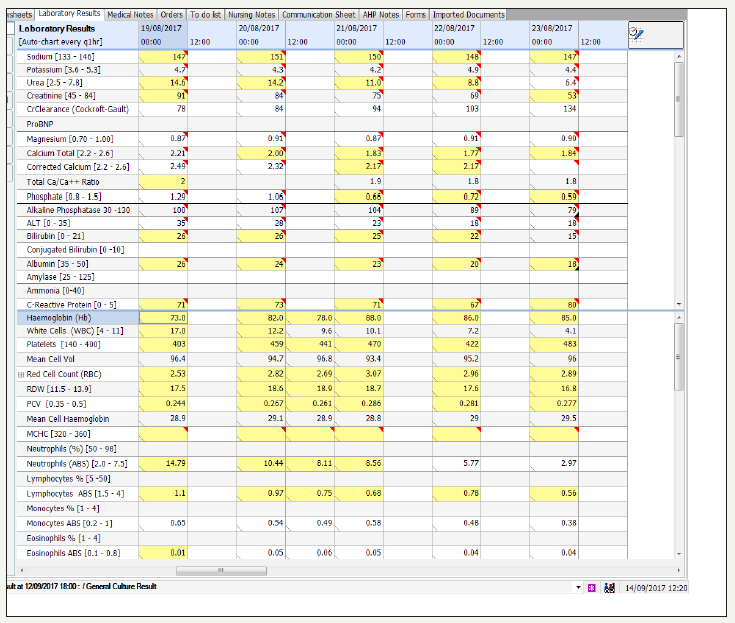

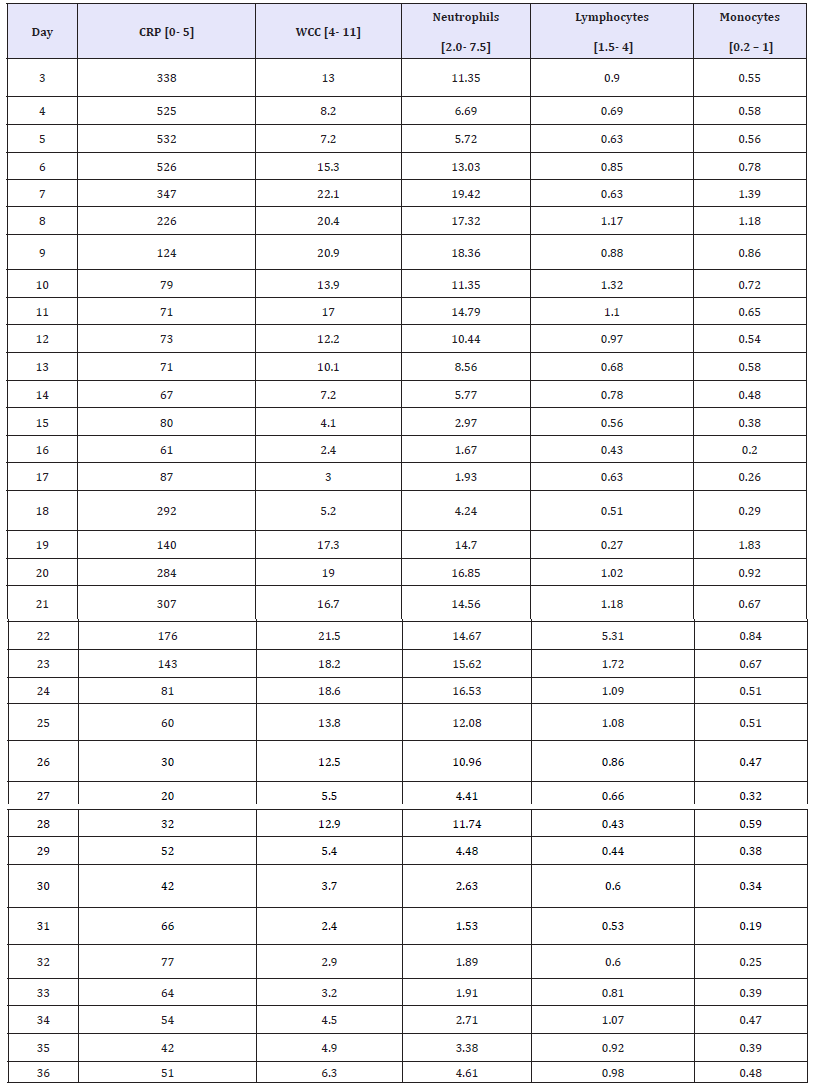

On day 26, Andilufungin was substituted in place of fluconazole. Patient stopped spiking temperature and clinically started to improve on day 27 (Figure 8). Interestingly, a marked drop in the patients’ white cell lineage (WCC) was noted on day 29, specifically a lymphopenia and monocytopenia, which fell further over the next couple of days, with a neutropenia developing on day 31 (Table 1).

Table 1: Results of the patient’s white cell count (WCC), neutrophil count, lymphocyte count and monocyte from ICU admission onwards.

figure 8: Flow sheet of the patient’s white cell lineage plummeting after starting Andilufungin and subsequent recovery of white cell lineage after stopping it.

It was thought that the leucopoenia was secondary to the antifungal. Andilufungin was stopped immediately after a multidisciplinary team meeting, whilst patient remained on meropenem, metronidazole and vancomycin [10]. The patient’s WCC showed improvement within the next 24 hours and continued to stabilise over the following days.

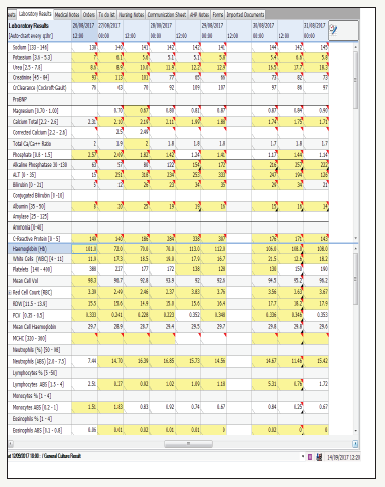

Patient subsequently had to be started on caspofungin on advice of microbiologist (Figure 9). She developed critical illness myopathy. She had a tracheostomy and prolonged wean [11,12]. Patient was on total parental nutrition with complete bowel rest. She continued a slow recovery. She was subsequently referred to a tertiary small bowel transplant and dysfunction management centre (Figure 10).

figure 9: Flow sheet of the patient’s white cell lineage recovered completely after stopping Andilufungin, but patient needed caspofungin cover after 48 hours.

figure 10: Results of the patient’s White Cell Count (WCC), neutrophil count, lymphocyte count and monocyte from ICU admission onwards, [normal reference ranges].

Conclusion

We present the case of a woman who developed selective bone marrow depression resulting in neutropenia, monocytopenia and lymphopenia after day five whilst on anidulafungin. To our knowledge this is the first documented case of such side effects associated with the use of anidulafungin. Clinicians should be aware the selective white cell lineage side effects, as it could result in significant risk of other infections in an already critically ill patient and risk prolonging their illness further especially in elderly patients.

References

- Kuti EL, Kuti JL (2010) Pharmacokinetics, antifungal activity and clinical efficacy of anidulafungin in the treatment of fungal infections. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 6(10): 1287-1300.

- Soldini S, Posteraro B, Vella A, De Carolis E, Borghi E, et al. (2017) Microbiological and clinical characteristics of biofilm forming Candida Parapsilosis isolates associated with fungaemia and their impact on mortality. Clin Microbial Infect 24(7): 771-777.

- De la Llama Celis N, Huarte Lacunza R, Gómez Baraza C, Cañamares Orbis I, Sebastián Aldeanueva M (2012) Echinocandins: searching for differences, the example of their use in patients requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Rev Esp Quimioter 25(4): 240-244.

- Bedin Denardi L, Pantella Kunz de Jesus F, Keller JT, Weiblen C, De Azevedo MI, et al. (2018) Evaluation of the efficacy of a posaconazole and anidulafungin combination in a murine model of pulmonary aspergillosis due to infection with Aspergillus fumigatus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 90(1): 40-43.

- Sucher AJ, Chahine EB, Balcer HE (2009) Echinocandins: the newest class of antifungals. Ann Pharmacother 43(10): 1647-1657.

- Vazquez JA, Sobel JD (2006) Anidulafungin: a novel echinocandin. Clin Infect Dis 43(2): 215-222.

- Kolbinger P, Gruber M, Roth G, Graf BM, Ittner KP (2018) Filter Adsorption of Anidulafungin to a Polysulfone-Based Hemofilter During CVVHD In Vitro. Artif Organs 42(2): 200-207.

- Chen Y, Mallick J, Maqnas A, Sun Y, Choudhury BI (2018) Chemo genomic profiling of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62(2).

- Berrio I, Maldonado N, De Bedout C, Arango K, Cano LE (2018) Comparative study for 147 Candida spp. identification and echinocandins susceptibility in isolates obtained from blood cultures in 15 hospitals, Medellin, Colombia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist pp. 254-260.

- National institute for health and care excellence (NICE). BNF: British National Formulary – Anidulafungin.

- Murdoch D, Plosker GL (2004) Anidulafungin. Drugs 64(19): 58-60

- Chen SC1, Slavin MA, Sorrell TC (2011) Echinocandin antifungal drugs in fungal infections: a comparison. Drugs 71(1): 11-41.

© 2018 Vikram Anumakonda. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)