- Submissions

Full Text

Clinical Research in Animal Science

Purpose and Farmers Trait Preference of Indigenous Cattle Reared in West Omo Zone, Southwestern, Ethiopia

Ashenafi Kidane and Worku Masho Bedane*

Department of Animal science, Ethiopia

*Corresponding author: Worku Masho Bedane, College of agriculture and natural resource, Department of Animal science, Ethiopia

Submission: July 19, 2022;Published: September 30, 2022

ISSN: 2770-6729Volume 2 - Issue 3

Abstract

The study was conducted to assess the purpose and trait preference of indigenous cattle reared in three ethnic community of west Omo zone, southwestern Ethiopia. Farmers’ and agro pastoralists’ attitudes toward cattle husbandry provide an opportunity for indigenous cow genetic improvement in the studied communities. A total of 180 household respondents were involved for interviews. In the Suri culture, blood suckled from cows or bulls was directly drunk or blended with milk and locally brewed beer. Milk yield, huge body size, fertility, physical attractiveness, udder and teat size, and coat color were all important factors in cow selection. Bulls were chosen based on their large body size, physical attractiveness, traction power, coat color, and temperament.

Keywords:Indigenous cattle; Trait preference; West Omo; Blood

Introduction

Due to its unique agro-ecology, geography, and closeness to Asia, where most domesticated cattle in Africa originated [1-3]. Ethiopia is home to a wide range of cattle breeds. When compared to other African countries, the country has the largest cattle population. According to [4] there are 60.39 million head of cattle in the United States, including at least 32 recognized indigenous breeds. Cattle are used for a variety of purposes throughout the country, including revenue, meat, milk, draught power, and savings, as well as cultural and ceremonial functions during festivals [5,6]. In the country, hides, horns, and manure are all important by-products of cattle [7,8,3]. In addition to milk and meat, the Suri community in western Ethiopia raises cattle for the purpose of giving blood [9]. According to [10] cattle were bred for the purpose of blood production in addition to milk production. These objectives make them suitable for the country’s smallholder and pastoralist communities. Ethiopia owns over 98.2% of Bos indicus and Taurine type (Sheko) cattle [11]. Native cattle have characteristics such as adaptation to little feed and water, disease challenge, severe hot and cold climatic conditions, and irregular drought times [12].

Farmers that use conventional selective breeding methods for their animals are able to preserve rich genetic resources. They usually choose the best breeding stock based on phenotypic characteristics. Their perceptions of genetic worth fluctuate from community to community, and as a result, various breeds are associated with different locations for certain purposes [13].

Some cow owners pick breeding stock based on the kind and shape of their horns, coat color, and conformation [14]. According to [15], disease resistance, drought tolerance, feed requirements, heat tolerance, milk yield, growth rate, fertility, marketability, meat quality, traction capability, milk/butter taste, teat/udder size/condition, and tail length (milk indicators), color, body condition, shape and size of the body, and horns were the parameters ranked as the relative importance of reasons for preferring specific cattle breeds given by livestock keel owners.

Material and Method

Description of the study area

West Omo Zone: The research was carried out in the West Omo zone of the Southern Nations Nationalities and People Region. For current assessment three ethnic communities (Dizi, Me’en, and Suri) were considered (WOZLFOR, 2019).

Site selection and sampling techniques

The research site and cattle owners were purposefully chosen because they were known to have a very high density of cattle herds. The researcher and the Weredas were picked from the west Omo zone stratified by raising communities of Dizi, Me’en, and Suri for a single stage field observation visit. Three kebeles representing those villages were purposefully chosen based on cattle population concentration. Enumerators randomly selected 180 farmers and pastoralists from certain rural kebeles and questioned them. We purposefully chose households with a minimum of five mature cattle and at least six years’ experience in cow rearing and who were willing to participate in the research. A total of 20% of identified cattle rearers were chosen at random for the study.

Result

Purpose of keeping cattle

Table 1 summarizes the findings for the purpose of cattle rearing in the three research communities. When compared to other livestock, cattle have multiple purposes. According to the results of individual and group talks with farmers and pastoralists in the study communities, The Dizi community’s responders kept cattle largely for drought resistance, followed by revenue and milk production. The Me’en village, like Dizi, relied on local cow genetic resources for drought power and milk, as well as a source of money. Cattle were primarily raised in Suri society for the purposes of blood, milk, and social security.

Table 1:Ranking of the Purpose of keeping cattle as indicated by respondents.

Index =Index = sum of [3 for rank 1 + 2 for rank 2 + 1 for rank 3] for particular purpose divided by sum of [3 for rank 1 + 2 for rank 2 + 1 for rank 3] for all purpose.

Bulls and cow’s trait preferences in the study communities

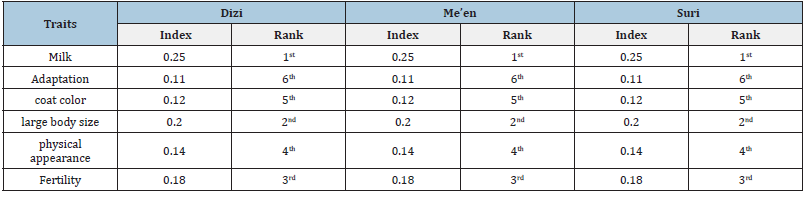

In our nation, genetic development for productive qualities in livestock, particularly cattle, has been gradual and insignificant. Table 2 summarizes the report on the respondent’s characteristic preferences in each of the three communities. Production qualities, such as milk supply, huge body size, fertility, and physical beauty, were the most desirable features for females in three societies. Milk from indigenous cattle is a valuable supply of milk and milk products, as well as a source of food and revenue for the family.

Table 2:Cows trait preference in the three communities of west Omo zone.

Index = sum of [6 for rank 1 + 5 for rank 2 + 4 for rank 3 +3 for rank 4+2 for rank 5+ 1for rank 6 +] for particular purpose divided by sum of [6 for rank 1 + 5 for rank 2 + 4 for rank 3 +3 for rank 4+2 for rank 5+ 1for rank 6] for all purpose.

Bull trait Preference in the study community

Table 3 shows the respondent’s trait preference for bull across the three groups. The Dizi community was chosen based on body size, traction power, physical attractiveness, adaption, temperament, and the existence of a hump and horn. Bulls are chosen by the Me’en community for their large body size, physical attractiveness, and traction force. Physical appearance and coat color (excluding black coat color) were valued more in the Me’en and Suri cultures, possibly for aesthetic rather than economic reasons.

Table 3:Male trait preference in Dizi, Me’en and Suri agro ecologies.

Index = sum of [8 for rank 1 + 7 for rank 2 + 6 for rank 3 +5 for rank 4+4 for rank 5+ 3 for rank 6 +2 for rank 7+1 for rank 8] for particular purpose divided by sum of [8 for rank 1 + 7 for rank 2 + 6 for rank 3 +5 for rank 4+4 for rank 5+ 3 for rank 6 +2 for rank 7+1 for rank 8] for all purpose.

Discussion

Purpose of keeping cattle in the study community

When compared to other animals in the research community, cattle serve a variety of uses, as seen in Table 1. The Dizi community’s responders kept cattle largely for drought resistance, followed by revenue and milk production. The primary source of revenue for the Dizi village was serial cropping, which was aided by the employment of bulls for drought power. The most important aspect of cattle in the study community was the income from cow sales, as well as milk and milk products [16,17]. The Me’en village, like Dizi, relied on local cow genetic resources for drought power and milk, as well as a source of money. Drought power is the backbone of agricultural power in developing nations. Hence, bulls with exceptional drought power, which is also linked to great muscularity, toughness, and tameness, are chosen [18,17].

Cattle were primarily raised in Suri society for the purposes of blood, milk, and social security. The community’s main source of nutrition is the blood of their livestock. Blood can be drunk alone, blended with milk, or mixed with ‘geso’ (a maize-based beer) among certain tribes [18]. The milk-blood mixture ‘regge hola’ was popular among young men in livestock camps, who drank it for its reputed vigor and health benefits [9]. Blood was used to produce blood sausages, infant biscuits, bread, and blood pudding throughout Europe and Asia [19]. Teenage girls and women from the settled world visit the cattle ranches to milk the ‘regge hola’ blood combination. Blood is collected from the jugular neck-vein of healthy and well-conformed cows, as in the Maasai or Pokot ethnic communities, and opened with a well-aimed tiny arrow device. The traditional Suri diet appears to have had a positive impact on their health: they were free of coronary heart disease, diabetes, tooth decay, obesity, and other ailments [9]. The three main types of Suri communal diet are meat, milk, and blood. Once a month, the community draws blood from their cow or ox’s jagular vein, which is deemed more effective than butchering the animal for meat supplies. Cattle flesh is served with considerable ceremony when they die or get old. The meat of slaughtered/dead oxen will be roasted and consumed by locals, relatives, or peers of the same age group. The animal’s owner refused to consume the meat of his own cow; a behavior frowned upon by the Suri society. Suri people do not eat or ingest row meat, which distinguishes them from other Ethiopian ethnic groups. It is forbidden for an animal owner who is grieving to consume the flesh of his own ox [9]. In lowland agro ecological, having a big herd of cattle was a sign of affluence and earned you a lot of respect. In the lowland agro-ecology society, those with 150-250 cattle enjoy a high social position and reputation. This was comparable to the previous study [20], which found a population of 200-300 cattle.

Cattle trait preferences by rearing communities

In our nation, cattle genetic development for productive qualities has been sluggish and minimal. Table 2 summarizes the report on the respondent’s characteristic preferences in each of the three communities. Milk supply, huge body size, fertility, and physical beauty were the most desirable features for cows in three societies. Milk from indigenous cattle is a valuable supply of milk and milk products, as well as a source of food and revenue for the family. Those cultures believed that a calf weaned from a largebodied cow would grow to be enormous. According to [3], female cattle were chosen first and foremost for their fertility, followed by milk output and body size. Cattle in the Mursi and Bodi communities in the Salamago area are mostly used for milk production [18].

Table 3 shows the raising groups’ predilection for bull traits. The Dizi community was chosen based on body size, traction power, physical attractiveness, adaption, temperament, and the existence of a hump and horn. Large bodies and large hump sizes are important for traction endurance and high market value. [3, 20]. Bulls are chosen by the Me’en community for their large body size, physical attractiveness, and traction force. They practiced agricultural and animal production, which is why traction power is regarded as a trait selection factor. When used as traction power, large body size and physical attractiveness are connected with market value and endurance [21]. The current conclusion is consistent with [21], who found that farmers’ coat color preferences are assessed in terms of adaptability to the local environment, particularly attractiveness to biting flies and economic gains from animal sales. Physical appearance and coat color were regarded highly, in the Me’en and Suri cultures, possibly for aesthetic rather than economic reasons [22,23].

Summary, Conclusion and Recommendation

Summary and conclusion

Cattle were raised for milk, blood, drought resistance, social security, and revenue generation. Suri people are mostly reliant on blood, blood combined with milk, and locally brewed ‘gesso’ beer. Milk production, huge body size, physical attractiveness, coat color, fertility, teat and udder size, and adaption were used to choose cows in the study ethnic community. Male cattle are also favored because of their huge body size, traction power, physical attractiveness, coat color, temperament, hump size, and adaptability. The features desired by those ethnic groups must be the basis for genetic progress.

References

- IBC (2009) Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Ethiopia’s 4th Country Report, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Ahmed AM, Simeon E, Yemesrach A (2004) Dairy development in Ethiopia. Intl Food Policy Resintant, p.73.

- Mulugeta FG (2015) Production system and phenotypic characterization of Begait cattle, and effects of supplementation with concentrate feeds on milk yield and composition of Begait cows in Humera ranch, Western Tigray, Ethiopia. AAU Institutional Repository, p.11.

- CSA Central Statistical Authority (2017) Agricultural Sample Survey. Report on Livestock and Livestock Characteristics (Private Peasant Holdings). [2009 E.C.], Statistical Bulletin 585.Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Volume II, p.188.

- Gizaw S (2011) Characterization and conservation of indigenous sheep genetic resources: A practical framework for developing countries, Volume 27.

- NABC (2010) Fact Sheet: Livestock Ethiopia, p. 31.

- Halderman M (2005) The political economy of pro-poor livestock policy making in Ethiopia, No. 855-2016-56233, Ethiopia.

- Koehler-Rollefson, Hartmut Meyer (2014) Access and benefit-sharing of animal genetic resources using the Nagoya Protocol as a framework for the conservation and sustainable use of locally adapted livestock breeds." ABS Capacity Development Initiative-implemented by the Deutsche Gesells chaftfür International eZusammenarbeit.

- Abbink GJ (2017) Insecure food. diet, eating and identity among the Ethiopian Suri people in the developmental age. African Study Monographs 38(3): 119-145.

- Terefe E (2010) Characterization of Mursi cattle breed in its production environment, in Salamago woreda, South-West Ethiopia, Haramaya University, Ethiopia.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency) (2017) Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia: Agricultural sample survey 2016/17 [2009 E.C.], Report on livestock and livestock characteristics (private peasant holdings). Statistical bulletin-585, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Volume 2.

- EBI (2016) Ethiopia’s Revised National Biodiversity strategy and Action Plan. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Getachew F, Geda G (2001) The Ethiopian Dairy Development, Draft Policy Document, MOA/FAO, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia.

- Tewelde G (2016) Studies on Morphometric Characteristics, Performance and Farmers’ Perceptions on Begait Cattle Reared in Western Tigray, Ethiopia." PhD diss., MSc Thesis. Hawassa University, Ethiopia, p. 51.

- Kisiangani E (2011) Conservation of indigenous breeds (Practical Action Brief). Practical Action Eastern Africa AAYMCA Building (Second Floor) Along State House Crescent.

- Mwacharo JM, Drucker AG (2005) Production objectives and management strategies of livestock keepers in South-East Kenya. Implications for a breeding programme. Tropical Animal Health and Production 37(8): 635-652.

- Endashaw T, Tadelle D, Aynalem H, Wudyalew M, Okeyo M (2012) Husbandry and breeding practices of cattle in Mursi and Bodi pastoral communities in Southwest Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research 7(45): 5986-5994.

- Amelmal A (2011) Phenotypic characterization of indigenous sheep types of Dawuro zone and Konta special woreda of SNNPR, Ethiopia." M. Sc. The-sis presented to the School of Graduate Studies of Haramaya University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.

- Wondatir Z (2010) Livestock production systems in relation with feed availability in the highlands and central rift valley of Ethiopia.

- Dereje B, Kefelegn K, Banarjee AK. On farm production systems characterization of indigenous cattle in Bako Tibe and Gobu Sayo Districts of Oromia Region, Ethiopia.

- Chali Y (2014) In situ phenotypic characterization and production system study of arsi cattle type in arsi highland of oromia region, Ethiopia. MSc. Thesis, Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia, pp. 26-87.

- Jack O (2015) Blood-derived products Hsieh Y-H, P. Revelation, and Science 1: No.01 1432H/2011.

- Getahun K, Anshiso D, Fantahun T (2017) Livestock price formation in suri pastoral communities in bench maji zone southwest Ethiopia hedonic property value approach. International Journal of Agricultural Economics 2(4): 90-95.

- Manyok P (2017) Cattle rustling and its effects among three communities (Dinka, Murle and Nuer) in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Nova Southeastern University, USA.

© 2022 Worku Masho Bedane. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)