- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Health and Social Care Professionals Experience of Psychological Safety within their Occupational Setting: A Thematic Synthesis Scoping Review Protocol

Josephine Hoegh, Gemma Rice, Shruti Shetty, Aoife Ure, Nicola Cogan and Nicola Peddie*

Department of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde, Scotland

*Corresponding author: Nicola Peddie, Department of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde, Scotland

Submission: April 16, 2024;Published: May 20, 2024

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume8 Issue5

Abstract

Psychological Safety (PS) in the workplace plays an essential role in helping Health and Social Care Professionals (HSCPs) function in interpersonally challenging and high stress work environments. While much of the research on PS, to date, has focused on teams, little work has sought to synthesis what is understood to be important to HSCPs’ in terms of their lived experiences of PS across diverse health and/or social care settings. A protocol for a scoping review qualitatively synthesizing primary research literature exploring barriers and enablers of PS as experienced by HSCPs was developed. This protocol outlines the planned procedures for a thematic synthesis scoping review. A systematic search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane library will be conducted, and the search results will be imported to Covidence where title and abstract screenings, full text screenings, and data extraction will occur. The scoping review will search databases for the timeframe of March 2004 to present. The scoping review will thematically synthesize qualitative data from primary research. The results of the scoping review will be used to examine key relationships and findings regarding enabling factors that help facilitate experiences of PS among HSCPs in the workplace as well as barriers to feeling PS. The findings will inform future research, protocols and interventions aimed at improving PS at the individual, team and organizational level across diverse health and social care settings.

Keywords:Psychological safety; Health and social care professional; Wellbeing, Scoping review; Qualitative

Introduction

Occupations in health and social care services such as nursing, medicine, social work, rehabilitation work and welfare work, are widely regarded as highly stressful [1-9] (Lamb & Cogan, 2016). A growing body of research suggests that the combination of exposure to multiple interpersonal demands, heavy emotional labour and traumatic stressors may have significant impacts on HSCPs and contribute towards the development of cardiovascular disease [10,11] and physical disorders [12,13]. HSCPs have been found to have a heightened susceptibility to poor mental health outcomes including burnout, anxiety, depression, chronic fatigue, PTSD and suicide compared to the general population [14-17] (Smith et al, 2021). Research has identified HSCPs to be among the highest suicide risk of any professional occupations [18]. Such risk factors have been further exacerbated by stressors associated with the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exerted significant mental and physical burden, especially on HSCPs operating in the front line of the COVID-19 care [19]. Consequently, there has been increased interest and urgency in understanding factors that can help mitigate against such adverse outcomes and help protect the mental and physical health of HSCPs in their places of work [2,3].

The importance of feeling psychologically safety at work

Psychological Safety (PS) is a construct that has received increased research attention given that it has been found to play an essential role in helping HSCPs function effectively in their occupational roles [20]. PS was first described by Schein & Bennis [21] as an essential step in the “unfreezing” process necessary for successful organizational learning and development. It was originally defined as an individual’s “sense of being able to show and employ oneself without fear of negative consequences to selfimage, status or career” [22]. It has been further characterized in the context of work teams as “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking” [23]. The construct of PS conceptualises the importance of mental health, wellbeing, and post-traumatic growth [24,25] and is commonly understood within organizational contexts as referring to the ability to be honest and show initiative as an individual or within a team [15,26]. It also encapsulates the extent to which an individual feels understood and cared for, capable of speaking up, socially engaged with others, and able to show compassion [25]. HSCPs that feel enabled to assess interpersonal risks, raise concerns and report near misses can also help minimize the incidence of medical errors [27], facilitate employee communication (Edmondson & Lei, 2014), improve teamworking [28] and increase patient safety [29]. It is imperative for health and social care workplace settings to be PS, so HSCPs are free to hear, learn and act more to improve the overall quality of patient care [30].

The importance of PS for the individual as well as within teams, has also gained attention in recent years with a comprehensive analysis of PS rooted in neurophysiology, psychology, and evolutionary theory informed by Polyvagal Theory ([31]; PVT). PVT outlines the multiple states of the nervous system activation; Ventral Vagal (VV), Sympathetic Activation (SA) and Dorsal Vagal (DV) which are related to PS. When stressed, individuals cannot remain in a state of SA or DV due to the amount of cortisol the body experiences, resulting in the activation of the body’s ‘fight or flight’. Given that HSCPs often work in highly stressful environments, this can neurologically alter their perceptions of reality and reduce their sense of PS. As a result, they may have increased sensitivity to pain [31] and may experience burnout (Szwamel et al., 2022).

The wellbeing of professionals in health and social care settings is vital as it is critical to offering patients’ safe care [32]. Despite the significance of PS for HSCPs’ wellbeing, lack of perceived PS is frequently reported among HSCPs resulting in hesitancy to speak up about problems for fear of retribution, not being heard, being blamed, or causing trouble [33]. Nonetheless, several studies suggest that a focus on enabling factors such as having a safety culture, continuous improvement culture, familiarity across teams, leader behavioral integrity, professional responsibility, and changeoriented leadership, can support PS in health and social care settings [28]. This highlights that having PS working environments as a priority can cultivate HSCPs’ wellbeing and help create a safe patient and staff working environment [34].

While much of the work on PS has sought to measure its impact across a range of occupational contexts [35-37], teams [28,34] and at the individual level [25,38], there is an emerging body of research focused on the lived experiences and perspectives of HSCPs themselves in terms of what it means to feel PS at work. More specifically, the importance of understanding factors which are perceived by HSCWs to help facilitate (enablers) or hinder (barriers) PS is the focus for this scoping review protocol. This protocol outlines the objectives and procedure for conducting a scoping review to thematically synthesize existing primary qualitative research data capturing HSCPs’ perspectives and experiences of PS in their places of work.

Objectives/research questions Primary question

A. What are HSCPs’ experiences of PS within their workplaces?

Secondary questions

A. How is PS conceptualised in the research literature?

B. What are the characteristics of participants included in

the sources of evidence identified?

C. What are the research methods and qualitative analytical

approaches that underpin the literature on PS as experienced

by HSCPs?

D. What factors are effective in facilitating (enablers) PS or

reducing (barriers) PS among HSCPs?

E. What gaps are there in the literature about PS as

experienced by HSCPs?

Method

The purpose of the scoping review method is to map a body of peer reviewed research literature with the intention to illuminate key characteristics, terms, methods, findings, and relevant gaps to inform future research (Gopalakrishnan & Ganeshkumar, 2013). The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology and checklist for conducting scoping reviews will be followed (Santos et al., 2018). In terms of reporting style, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) will be used [39]. The scoping review will adhere to the ENTREQ statement (2012) and utilise thematic synthesis [40]. The scoping review was prospectively registered with OSF (https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/4u7hq) and further developed accordingly.

Inclusion criteria

Population: The study population must include specific mention of ‘health and/or social care professional’ and their experiences of individual or group PS in their work setting. In studies where accounts of HSCPs’ own understandings of PS are included, their own use of terminology (e.g. feeling safe, social engagement) will be acknowledged. Only qualitative studies will be included so as to capture the personal experiences and perspectives of HSCPs’ in terms of PS.

Context: The context is to explore research published worldwide.

Date of publication: From March 2004-current (20-year time span).

Types of evidence: Primary research, qualitative, or mixed methods research which includes significant qualitative data.

Languages: English only (based on this being the primary language spoken within the context being researched).

Exclusion criteria: Studies that do not include peer reviewed primary qualitative data, such as quantitative studies, reviews, opinion texts and grey literature will not be sourced; studies which have not been published in English; and studies published before 2004-participants who do not work within the health and social care occupations.

Calibration: Prior to commencing the screening process, a calibration exercise will be conducted between reviewers [41]. This will consist of selecting 10% of the papers for independent screening by each reviewer. If a high level of agreement among reviewers is not achieved (e.g., lower than 90%) [42], the reviewers will discuss their points of disagreement with the goal of 90% or better agreement [43]. If necessary, validation by a third reviewer will be sought.

Sources of evidence: Two levels of screening will be used to identify sources of evidence for inclusion in the scoping review: (a) study selection - review title and abstract, (b) study screening - review the full text. Data screening, charting and literature quality assessments will be managed using Rayyan software to sift, categorize, sort and store findings according to key issues and themes [44]. Any articles identified as relevant based on the title and abstract will be reviewed at full-text level. A PRISMA flowchart will be used to report the final number of the study selection process.

Search strategy: The search strategy for this scoping review will be as comprehensive as is possible and appropriate within the parameters of this protocol. This will be developed with the help of an expert health librarian and will be peer-reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines [45]. In accordance with the JBI guidelines for conducting a scoping review, a three-step search strategy process will be implemented. The first step will involve performing an initial search of two databases; namely MEDLINE (Ovid) and APA Psyc Info. Text words used in the title and abstracts of relevant papers identified within this search will be extracted and analyzed alongside the index terms describing articles. These terms will then be used in step two where a further search will be conducted across all relevant databases (MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane library). Lastly, step three will include examining reference lists of articles which have been included in the review to identify further relevant sources. Grey literature will not be included in the final review. All search strategies will be submitted with the scoping review as supplementary material [46]. Any limitations in terms of the comprehensive nature of this review will be justified within the final scoping review.

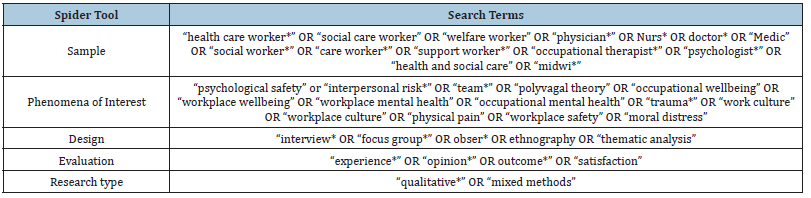

The SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) tool will be utilised as the source for the search strategy [47]. This tool is used to define key elements of the review question and search strategy. The search strategy to be employed in detailed in Table 1.

Table 1:Obser* will be removed from the search for Web of Science.

Data extraction process: Data will be extracted, duplicates will be removed, and titles and abstracts will be screened. Papers which meet the inclusion criteria will be retained for full-text screening by four independent reviewers who will each screen 50% of the papers. If an abstract did not provide sufficient exclusion information, the article was obtained for full-text screening. Two independent reviewers will screen full papers using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any uncertainty will be resolved through discussion. Data extracted from selected studies will include author, publication year, title, participant information, context, methodology, results, themes, limitations and type of analysis used. Data will be charted using a data extraction table, based on a model recommended by the JBI [48].

Risk of bias: The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research is a validated tool for quality assessing qualitative research, and it is endorsed by Cochrane and the World Health Organization [49]. The checklist is widely used, and recommended for novice researchers, and is known to be succinct and effective [50]. Furthermore, the checklist was developed for use in health-related research [49]. The CASP checklist tool allows the researchers to systematically evaluate published papers by looking at the reliability, relevance and conclusions drawn. The quality of included papers will be assessed using the tool conducted by four reviewers, with each reviewer assessing 50% of the included studies. Any disagreements will be resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis: A thematic synthesis of qualitative data based on the method described by Thomas & Harden [40] will be utilised to synthesise and manage the data extracted, and themes emphasising key issues and messages will be created. The first step of data synthesis will involve line-by-line coding of primary research. These codes will then be re-examined to identify similarities- a process termed “axial-coding” [51]. The codes will be re-assessed to ensure they capture the data accurately [52]. Following this, the codes will be organized into logical groups to develop descriptive themes. Reviewers will then make inferences about the experiences captured by the descriptive themes to generate analytical themes.

Results

The scoping review will extract qualitative data from the articles which are found via the searches. A thematic synthesis of the themes developed from the primary data will be presented and a diagrammatic thematic map of the enabler and barrier themes identified [53]. A tabular presentation of the data for aspects such as participant characteristics, study methodology, will be reported. This method of reporting will be used to highlight what is known about the key topics concerning experiences of PS among HSCPs in relation to the research questions and to identify gaps in knowledge. These methods have been chosen in accordance with the objectives of the scoping review [54,55].

Discussion

This protocol outlines the rationale and proposed questions and methods to be utilized for conducting a scoping review on HSCPs’ experiences of PS in their work settings as well as their perspectives concerning perceived enabling factors and barriers to PS. A discussion will examine the key relationships and findings identified in the results section in relation to HSCPs’ experiences of PS in their work settings. The limitations of the review will be considered. The scoping review will produce important new information on PS as experienced by HSCPs, conceptual understandings of PS, characteristics of participants, study design and methodology and factors which enable or act as barriers to PS. It will also highlight challenges and gaps in the existing evidence base with recommendations for key areas for future research. The findings will be disseminated through health and social care services, professional and NHS bodies, third sector organizations, conferences and research papers. The review will help inform the development of impactful resources and help build an evidence base on PS in health and social care settings for HSCPs, academics, policy makers and statutory and third sector agencies with the aim of raising awareness and improving research in this area. Lastly, the review will be targeted across a broad scope of disciplines concerning PS, which will provide the opportunity to elicit more generalizable findings that can directly inform practice and policy decisions within these disciplines.

Conclusion

This protocol details the thematic synthesis of primary qualitative data to be presented in the scoping review exploring HSCP’s perspectives and experiences of PS in their work settings. The review will be able to identify what existing primary research has found in terms of factors which help to facilitate PS, as well as identifying factors which can negatively affect health and social care workers experience of PS. It is envisaged that by being able to recognize what helps and hinders PS in health and social care setting, interventions may be designed and implemented which could help to foster an environment which contributes to an increased sense of PS for both HSCPs and patients in their care.

References

- Ding Y, Qu J, Yu X, Wang S (2014) The mediating effects of burnout on the relationship between anxiety symptoms and occupational stress among community healthcare workers in China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 9(9): e107130.

- Cogan N, Archbold H, Deakin K, Griffith B, Sáez Berruga I, et al. (2022) What have we learned about what works in sustaining mental health care and support services during a pandemic? Transferable insights from the COVID-19 response within the NHS Scottish context. International Journal of Mental Health 51(2): 164-188.

- Cogan N, Kennedy C, Beck Z, McInnes L, MacIntyre G, et al. (2022) ENACT study: What has helped health and social care workers maintain their mental well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic? Health & Social Care in the Community 30(6): e6656-e6673.

- Charzyńska E, Habibi Soola A, Mozaffari N, Mirzaei A (2023) Patterns of work-related stress and their predictors among emergency department nurses and emergency medical services staff in a time of crisis: A latent profile analysis. BMC Nursing 22(1): 98.

- Chirico F, Afolabi AA, Ilesanmi OS, Nucera G, Ferrari G, et al. (2021) Prevalence, risk factors and prevention of burnout syndrome among healthcare workers: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of Health and Social Sciences 6(4): 465-491.

- Kinman G, Teoh K, Harriss A (2020) Supporting the well-being of healthcare workers during and after COVID-19. Occupational Medicine 70(5): 294-296.

- Merrick AD, Grieve A, Cogan N (2017) Psychological impacts of challenging behaviour and motivational orientation in staff supporting individuals with autistic spectrum conditions. Autism 21(7): 872-880.

- Montero-Tejero DJ, Jiménez-Picón N, Gómez-Salgado J, Vidal-Tejero E, Fagundo-Rivera J (2024) Factors influencing occupational stress perceived by emergency nurses during prehospital care: A systematic review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 17: 501-528.

- Singh J, Karanika-Murray M, Baguley T, Hudson J (2020) A systematic review of job demands and resources associated with compassion fatigue in mental health professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(19): 6987.

- Backé EM, Seidler A, Latza U, Rossnagel K, Schumann B (2012) The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 85(1): 67-79.

- Ezber R, Gülseven ME, Koyuncu A, Sari G, Şimşek C (2023) Evaluation of cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthcare workers. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review 25(2): 150-154.

- Pérez-Valdecantos D, Caballero-García A, Del Castillo-Sanz T, Bello HJ, Roche E, et al. (2021) Stress salivary biomarkers variation during the work day in Emergencies in healthcare professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(8): 3937.

- Rice V, Glass N, Ogle KR, Parsian N (2014) Exploring physical health perceptions, fatigue and stress among health care professionals. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 7: 155-161.

- Fronteira I, Mathews V, Dos Santos RLB, Matsumoto K, Amde W, et al. (2024) Impacts for health and care workers of Covid-19 and other public health emergencies of international concern: Living systematic review, meta-analysis and policy recommendations. Human Resources for Health 22(1): 10.

- Isobel S, Thomas M (2021) Vicarious trauma and nursing: An integrative review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 31(2): 247-259.

- Purdy LM, Antle BF (2021) Reducing trauma in residential direct care staff. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 39(2): 1-13.

- Umbetkulova S, Kanderzhanova A, Foster F, Stolyarova V, Cobb-Zygadlo D (2024) Mental health changes in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Evaluation & the Health Professions 47(1): 11-20.

- Awan S, Diwan MN, Aamir A, Allahuddin Z, Irfan M, et al. (2022) Suicide in healthcare workers: Determinants, challenges, and the impact of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 792925.

- Agata S, Grzegorz W, Ilona B, Violetta K, Katarzyna S (2023) Prevalence of burnout among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors-a scoping review. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 36(1): 21.

- Ahmed F, Xiong Z, Faraz NA, Arslan A (2023) The interplay between servant leadership, psychological safety, trust in a leader and burnout: Assessing causal relationships through a three-wave longitudinal study. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics 29(2): 912-924.

- Schein EH, Bennis WG (1965) Personal and organizational change through group methods: The laboratory approach. John Wiley & Son, New York, USA.

- Kahn WA (1990) Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal 33(4): 692-724.

- Edmondson A (1999) Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly 44(2): 350-383.

- Sullivan CM, Goodman LA, Virden T, Strom J, Ramirez R (2018) Evaluation of the effects of receiving trauma-informed practices on domestic violence shelter residents. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 88(5): 563-570.

- Morton L, Cogan N, Kolacz J, Calderwood C, Nikolic M, et al. (2022) A new measure of feeling safe: Developing psychometric properties of the Neuroception of Psychological Safety Scale (NPSS). Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

- Remtulla R, Hagana A, Houbby N, Ruparell K, Aojula N, et al. (2021) Exploring the barriers and facilitators of psychological safety in primary care teams: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research 21(1): 1-12.

- Okuyama A, Wagner C, Bijnen B (2014) Speaking up for patient safety by hospital-based health care professionals: A literature review. BMC Health Services Research 14: 1-8.

- Donovan R, McAuliffe E (2020) A systematic review exploring the content and outcomes of interventions to improve psychological safety, speaking up and voice behaviour. BMC Health Services Research 20(1): 1-11.

- Grailey KE, Murray E, Reader T, Brett SJ (2021) The presence and potential impact of psychological safety in the healthcare setting: An evidence synthesis. BMC Health Services Research 21(1): 1-15.

- Harrison C (2020) Psychological safety and why it matters, NHS Providers, London, UK.

- Porges SW (2011) The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company, New York, USA.

- Kessel M, Kratzer J, Schultz C (2012) Psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and creative performance in healthcare teams. Creativity and Innovation Management 21(2): 147-157.

- Moore L, McAuliffe E (2012) To report or not to report? Why some nurses are reluctant to whistleblow. Clinical Governance: An International Journal 12(4): 332-342.

- Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC (2006) Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 27(7): 941-966.

- Edmondson AC, Higgins M, Singer S, Weiner J (2016) Understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: A comparative perspective. Research in Human Development 13(1): 65-83.

- Frazier ML, Fainshmidt S, Klinger RL, Pezeshkan A, Vracheva V (2017) Psychological safety: A meta‐analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology 70(1): 113-165.

- Newman A, Donohue R, Eva N (2017) Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review 27(3): 521-535.

- Poli A, Miccoli M (2024) Validation of the Italian version of the Neuroception of Psychological Safety Scale (NPSS). Heliyon 10(6): e27625.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, Brien KO, Colquhoun H, et al. (2018) PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. American College of Physicians 169(7): 467-473.

- Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8(1): 1-10.

- Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, et al. (2012) What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Medical Research Methodology 12: 1-10.

- Thomas A, Lubarsky S, Varpio L, Durning SJ, Young ME (2020) Scoping reviews in health professions education: Challenges, considerations and lessons learned about epistemology and methodology. Advances in Health Sciences Education 25(4): 989-1002.

- Mak S, Thomas A (2022) Steps for conducting a scoping review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 14(5): 565-567.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 5: 210.

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, et al. (2016) PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 75: 40-46.

- Munn Z, Pollock D, Price C, Aromataris E, Stern C, et al. (2023) Investigating different typologies for the synthesis of evidence: A scoping review protocol. JBI Evidence Synthesis 21(3): 592-600.

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A (2012) Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research 22(10): 1435-1443.

- Khalil H, Peters MD, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Alexander L, et al. (2021) Conducting high quality scoping reviews-challenges and solutions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 130: 156-160.

- Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM (2020) Optimising the value of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences 1(1): 31-42.

- Nadelson S, Nadelson LS (2014) Evidence‐based practice article reviews using CASP tools: A method for teaching EBP. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing 11(5): 344-346.

- Fisher M, Qureshi H, Hardyman W, Homewood J (2006) Using qualitative research in systematic reviews: Older people's views of hospital discharge, Social Care Institute for Excellence, London, UK.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’brien K, Colquhoun H, et al. (2016) A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 16: 1-10.

- Hamel C, Michaud A, Thuku M, Skidmore B, Stevens A, et al. (2021) Defining rapid reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 129: 74-85.

- Kirby JN, Doty JR, Petrocchi N, Gilbert P (2017) The current and future role of heart Rate variability for assessing and training compassion. Frontiers in Public Health 5: 40.

- Mok MCL, Schwannauer M, Chan SWY (2019) Soothe ourselves in times of need: A qualitative exploration of how the feeling of ‘soothe’ is understood and experienced in everyday life. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory Research and Practice 93(3): 587-620.

© 2024 Nicola Peddie. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)