- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Creation of the Healthcare Provider LGBTQ+ Knowledge and Attitudes Inventory

Cage SA1*, Decker M2, Warner LK3, Warner BJ4, Goza JP5, Vela L6, Skowron P7,8 and Wang A7,8

1The University of Texas at Tyler, USA

2The University of Texas at Arlington, USA

3Creighton University, USA

4Grand Canyon University, USA

5Collin College, USA

6University of Arkansas, USA

7The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler, USA

8UT Health East Texas, USA

*Corresponding author: Cage SA, The University of Texas at Tyler, USA

Submission: October 26, 2023;Published: November 24, 2023

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume8 Issue4

Abstract

Discrimination and harassment of LGBTQ+ healthcare professionals and patients has become increasingly well documented in the current literature. These issues can potentially lead to recruitment and retention issues related to LGBTQ+ healthcare professionals, and poorer outcomes for LGBTQ+ patients. In order to address these issues, it is important to have a better description of the environment in which LGBTQ+ individuals are administering and receiving healthcare. One method of gaining this better description is to be able to accurately capture the knowledge of and attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals and issues facing the LGBTQ+ community among healthcare providers. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to create an instrument designed to measure the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals related to LGBTQ+ persons and the issues they face. Upon recruiting a panel of 15 healthcare professionals the Delphi technique was used in a similar manner to that which was performed in previous studies in which survey instruments and consensus statements were created. Following rating and ranking of the statements and questions presented to the panel, a total of 14 statements to measure attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals and eight questions to measure knowledge of LGBTQ+ individuals were included in the final instrument. While the instrument still requires further study to establish reliability and validity, the survey is presented for consideration and use in future research projects.

Introduction

As of 2023, it is estimated that 7.2% of the United States adult population openly identifies as a sexual orientation or gender identity within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer non-heterosexual identity and orientation (LGBTQ+) community [1]. Additionally, previous findings have shown that there are over 8 million workers in the United States over the age of 16 that identify as LGBTQ+ [2]. Prior to the Supreme Court ruling on Bostock v Clayton County in 2020, 44% of LGBTQ+ employees in the United States did not have protections against discrimination and unjust treatment in the workplace [3]. Without these protections, LGTBQ+ persons have been subject to discrimination and harassment in the workplace, that has had negative consequences for their health and wellbeing [4,5]. As a result, these individuals are more likely to report lower job satisfaction and commitment to their place of employment [4,5]. While the experiences of LGBTQ+ persons working in the healthcare setting is understudied, it stands to reason that they are not unaffected by the previously mentioned findings. In fact, previous research has reported that LGBTQ+ athletic trainers experience issues with discrimination and harassment in their workplace in part due to their status as minorities [6,7]. It was also found that 17% of LGBTQ+ physicians participating in a previous study were denied privileges, promotion, or employment based on their sexual identity [8]. An additional 34% reported verbal harassment by professional colonies, 37% reported social ostracization, 52% had witness substandard care or denial of care for LGBTQ+ patients, and 88% had heard colleagues demean LGBTQ+ patients during clinical encounters [8]. Later research showed that while conditions for LGBTQ+ physicians had improved during the time that had passed since the previous study, at least one third of participants still reported experiencing harassment and social ostracization [9]. Nurses that are members of the LGBTQ+ community have also voiced the need for procedural, cultural, and infrastructural changes that would need to take place in their workplaces to feel included [10].

While the level of adversity faced by LGBTQ+ healthcare professionals warrants research to define and describe potential issues being faced, patient care is also impacted by negative views held against LGBTQ+ individuals. Previous authors have found that there are instances where LGBTQ+ patients may not feel safe or comfortable seeking care from a healthcare professional because of previous experience with discrimination and mistreatment by providers [11]. These feelings may result in patients not seeking timely healthcare for fear of further discrimination or not being accepted as a patient [11]. Furthermore, it appears that physicians and other healthcare providers are receiving little or no training on issues facing their LGBTQ+ patients as part of formal medical education and training [7,12,13]. In order to design and assess interventions to address issues facing the LGBTQ+ community, a full description of the issues being faced is necessary. One way to describe the issues being faced is to determine the attitudes and knowledge of healthcare providers related to LGBTQ+ issues. The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale (LGBKAS) is one such validated method of measuring knowledge and attitudes of individuals toward LGBTQ+ persons [14,15]. While the LGB-KAS has been validated over multiple populations, it does not include questions specific to attitudes toward LGBTQ+ persons that are specific to healthcare. Creation of such an instrument would be valuable for describing the current knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals related to LGBTQ+ patients. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to create the Healthcare Provider LGBTQ+ Knowledge and Attitudes Inventory, a survey instrument designed to measure the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals related to LGBTQ+ persons and the issues they face.

Methods

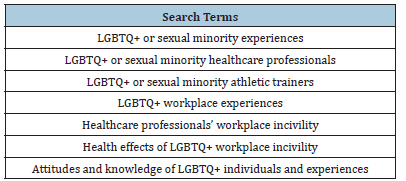

A review of the currently available literature was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, and the library database of a public institution of higher education to locate published materials that could contribute to an initial list of statements and questions to utilize in the Delphi process. Ultimately, 44 sources were utilized in the creation of the literature review [1-44]. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the search terms used during the review of literature related to issues facing LGBTQ+ healthcare providers and patients.

Table 1:Search terms used for literature review.

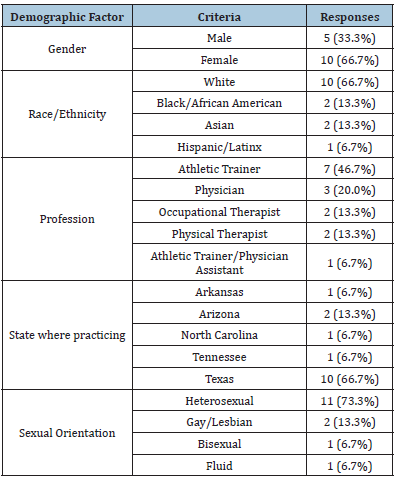

Table 2:Panel demographic information.

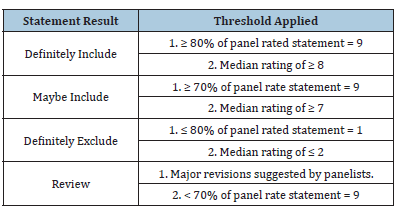

Upon completion of the review of literature, a panel of 15 healthcare professionals (34±4 years of age; 10± 5 years of healthcare professional experience) were invited to participate in a series of online surveys to assist with the creation of the instrument. Demographic information for the panel can be found in Table 2. Once demographic information was collected from the panelists, the Delphi technique was used in a similar manner to that which was performed in previous studies in which survey instruments and consensus statements were created [45-47]. Panelists who were currently credentialed healthcare professionals were independently recruited to participate based on likelihood of response. Panelists were informed of the purpose of the surveys they would be completing, as well as the potential significance of the creation of the proposed instrument. Panelists were then surveyed on a series of statements regarding attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals and issues, and on questions regarding knowledge of LGBTQ+ individuals and issues. Panelists were asked to rate each statement and question based off whether or not they felt it warranted inclusion in the final survey instrument (1=Definitely do NOT include to 9=Definitely include). Using the protocol outlined in Table 3, all statements were assessed by the primary investigator to determine if they warranted inclusion, exclusion, or modification.

Table 3:Statement inclusion key.

Following exclusion and revision of statements and questions, panelists were then asked to rank the statements and questions that remained from most to least important to include in the final instrument. Statements were ranked with the intent of including 14 statements in the final instrument, and questions were ranked with the intent of including eight questions in the final instrument. These numbers were chosen to keep the final instrument to 22 questions, not counting demographic information. Emphasis was placed on statements related to attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals and issues, as previous research has suggested that positive attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals and issues may lead to an individual being willing to improve their knowledge [18,19].

Results

Following the literature review, 24 statements and 12 questions were developed. The statements sought to gather information about attitudes related to LGBTQ+ individuals and the issues faced by the LGBTQ+ community. The questions sought to gather information on the current level of knowledge individuals held related to LGBTQ+ individuals and the issues faced by the LGBTQ+ community. All 15 panelists participated in the initial rating of statements and questions, with six providing comments and suggested revisions. After the rating of the original 24 statements and 12 questions was completed, 21 statements and 10 questions remained unmodified, two statements and two questions were excluded, and one statements was presented to members of the panel for modification. Following modification of the statement, it was included in the second round of panelist feedback for ranking. A total of 8 panelists responded to the second round of surveying, representing a 53.3% completion rate. Once ranking was complete, the 14 highest ranked statements and eight highest ranked questions were included in the final draft of the survey instrument. The final draft of the survey instrument can be found in Appendix A.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop a survey instrument designed to measure healthcare providers’ attitudes toward and knowledge of LGBTQ+ individuals and the issues faced by the LGBTQ+ community. The review of literature resulted in the creation of 24 statements and 12 questions. Following a survey rating the importance of including each statement and questions, 22 statements and 10 questions were included in a ranking process to develop a final consensus on the most valuable statements and questions for the final instrument. Ultimately, the goal of this process was to reach a level of agreement based off practitioner opinion to create a survey instrument that would provide an accurate means of measuring attitudes toward, and knowledge of LGTBQ+ individuals and issues faced by the LGBTQ+ community. This method was chosen based off the success of using it in other research projects where a consensus among healthcare providers was the goal [45-47]. The Delphi technique has been utilized in other research studies to reach consensus on statements and other instruments in the past [45-47]. It has been stated that this technique is highly valuable when used for establishing a consensus on subjects or phenomena that are not well document in researchbased literature [46].

The authors encourage all researchers, healthcare professionals, and healthcare administrators to review and consider the instrument carefully prior to use. While this survey instrument was created using validated techniques and a thorough review of the currently available literature, further research is required to ensure the reliability and validity of the instrument. This initial version of the survey instrument should be used for these measures of validity and reliability, with the intent of providing recommendations for future revisions. Extenuating variables such as state and federal regulations, educational accreditation standards, political and cultural beliefs, and personal experiences may affect the answers provided by individuals taking this survey instrument. The role of these variables in instrument scores should be address in future research to determine their impact. Although the panel was able to provide responses resulting in a consensus on the included statements and questions, this study did have limitations. The review of literature was designed to provide insights into structuring the initial statements and questions. However, the number of high-quality studies was lacking when searching for studies that assessed patient reported outcome measures among LGBTQ+ patients, curricula on LGBTQ+ patient needs in healthcare profession education programs, employment opportunities for LGBTQ+ healthcare professionals, and workplace incivility for LGBTQ+ healthcare professionals. Furthermore, the scope of the study did not take into account practice setting, or physician specialty, of the healthcare professionals involved as panelists. Future research should examine differences in attitudes toward and knowledge of LGBTQ+ individuals and issues facing the LGBTQ+ community among healthcare professionals from different practice settings. A final limitation is that the Delphi technique has been suggested to not meet the same standards as other scientific methods [46].

Conclusion

The final draft of the Healthcare Provider LGBTQ+ Knowledge and Attitudes Inventory provides an instrument for measuring the knowledge of and attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals and issues facing the LGBTQ+ community among healthcare providers.

This survey instrument provides an instrument for researchers, healthcare professionals, and healthcare professional educators seeking to determine the need for, and effectiveness of interventions designed to improve access to equal care for LGBTQ+ patients. This survey also provides an instrument for researchers and healthcare administrators seeking to determine the need for, and effectiveness of interventions designed to improve workplace civility, employee recruitment, and employee retention for LGBTQ+ patients. This instrument is presented with the intent of encouraging fellow researchers to perform studies to determine the validity and reliability of the survey for its proposed uses. With further research, this instrument has the potential to serve as a viable tool for multiple healthcare professions, including those that would find value in the materials published in COJ Nursing & Healthcare.

Appendix A

Healthcare Provider LGBTQ+ Knowledge and Attitudes

Inventory

Attitudes

Please answer the following prompts on the following scale:

1) Strongly Disagree 2) Disagree 3) Somewhat Disagree 4)

Somewhat Agree 5) Agree 6) Strongly Agree

A. I have conflicting attitudes or beliefs about LGBTQ+

people.

B. It is important to me to avoid interactions with LGBTQ+

individuals.

C. I have close friends who are members of the LGBTQ+

community.

D. I have close friends who are members of the LGBTQ+

community.

E. I have difficulty reconciling my religious beliefs with my

interest in being accepting and inclusive of LGBTQ+ people.

F. I would be unsure what to do or say if I encountered an

LGBTQ+ person.

G. Hearing about a hate crime against an LGBTQ+ person

would not bother me.

H. I think marriage should be legal for couples in the LGBTQ+

community.

I. I keep my religious views private in order to accept

LGBTQ+ people.

J. I conceal my negative views toward LGBTQ+ people when

I am with someone who doesn’t share my views.

K. Health Benefits should be available as equally to spouses

from the LGBTQ+ community as they are to any other legally

married couple.

L. I am more comfortable supporting civil rights initiatives

for sexual minorities (gay, lesbian, bisexual, etc.) than supporting

civil rights initiatives for gender minorities (transgender, nonbinary,

intersex, etc.)

M. I am able to treat a patient with the same level of dignity,

care, and consideration regardless of their sexual orientation.

N. I am able to treat a patient with the same level of dignity,

care, and consideration regardless of their gender identity.

References

- Jones JM (2023) US LGBT identification steady at 7.2%. Gallup News, USA.

- Conron KJ, Goldberg SK (2023) LGBT people in the us not protected by state non-discrimination statues. Williams Institute, USA.

- Totenberg N (2020) Supreme court delivers major victory to LGBTQ employees. National Public Radio, Washington DC, USA.

- Singh RS, O Brien WH (2020) The impact of work stress on sexual minority employees: Could psychological flexibility be a helpful solution? Stress and Health 36(1): 59-74.

- Pereira H (2022) The impacts of sexual stigma on the mental health of older sexual minority men. Aging & Mental Health 26(6): 1281-1286.

- Crossway A, Rogers SM, Nye EA, Games KE, Eberman LE (2019) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer athletic trainers: Collegiate student-athletes’ perceptions. Journal of Athletic Training 54(3): 324-333.

- Nye EA, Crossway A, Rogers SM, Games KE, Eberman LE (2019) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer patients: Collegiate athletic trainers’ perceptions. Journal of Athletic Training 54(3): 334-344.

- Schatz B, O Hanlan K (1994) Anti-gay discrimination in medicine: Results of a national survey of lesbian, gay and bisexual physicians. American Association of Physicians for Human Rights, San Francisco, California, USA.

- Eliason MJ, Dibble SD, Robertson P (2011) Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender physicians’ experiences in the workplace. Journal of Homosexuality 58(10): 1355-1371.

- Eliason MJ, DeJoseph J, Dibble S, Deevey S, Chinn P (2011) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning nurses’ experiences in the workplace. Journal of Professional Nursing 27(4): 237-244.

- Wierenga CE, Kaye WH, Brown TA, De Benedetto AM, Donahue JM (2020) Examining day hospital treatment outcomes for sexual minority patients with eating disorders. Journal of Eating 53(10): 1657-1666.

- Eliason MJ, Chinn PL (2018) LGBTQ cultures: What health care professionals need to know about sexual and gender diversity. (3rd edn), Wolter Kluwer Health, Philadelphia, USA.

- Jackman KB, Bosse JD, Eliason MJ, Hughes TL (2019) Sexual and gender minority health research in nursing. Nursing Outlook 67(1): 21-38.

- Raju D, Beck L, Azuero A (2019) A comprehensive psychometric examination of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale for Heterosexuals (LGB-KASH). Journal of Homosexuality 66(8): 1104-1125.

- Worthington RL, Becker-Schutte AM, Dillon FR (2005) Development, reliability and validity of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale for Heterosexuals (LGB-KASH). Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(1): 104-118.

- Darr B, Kibbey T (2016) Pronouns and thoughts on neutrality: Gender concerns in modern grammar. Pursuit 7(1): 71-84.

- Nye EA, Walen DR, Rogers SM (2019) Athletic trainers perceptions about collegiate transgender student-athletes’ unfair advantage in sport participation. Journal of Athletic Training 54(6S): S72.

- Goza PJ, Cage SA, Decker M, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM (2021) LGB-KASH and shortened workplace incivility scores among athletic trainers: A pilot study. Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine 7(5): 674-679.

- Cage S, Decker M, Eberman L, Warner B, Goza J (2022) LGB-KASH and shortened workplace incivility among NCAA division III coaches. International Journal of Advanced Multidisciplinary Research and Studies 2(4): 645-651.

- Bader E (2020) Understanding LGBTQ+ athletic healthcare: Athletes, athletic trainers and their perceptions. Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences: Official Journal of the Ohio Athletic Trainers Association 6(1).

- Behar Horenstein LS, Morris DR (2015) Dental school administrators’ attitudes towards providing support services for LGBT-identified students. Journal of Dental Education 79(8): 965-970.

- Brown KD, Sessanna L, Paplham P (2020) Nurse practitioners’ and nurse practitioner students’ LGBT health perception. The Journal of Nurse Practitioners 16(4): 262-266.

- Carabez R, Pellilgrini M, Mankovitz A, Eliason M, Ciano M, et al. (2015) Never in all my years…: Nurses’ education about LGBT health. Journal of Professional Nursing 31(4): 323-329.

- Casey LS, Reisner SL, Findling MG, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, et al. (2019) Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer Americans. Health Services Research 54(S2): 1454-1466.

- Chan CD (2019) Broadening the scope of affirmative practices for LGBTQ+ communities in career services: Applications from a systems theory framework. Career Planning & Adult Development Journal 35(1): 6-21.

- Cech EA, Rothwell WR (2020) LGBT workplace inequality in the federal workforce: Intersectional processes organizational contexts, and turnover considerations. ILR Review 73(1): 25-60.

- Cunningham GB, Hussain U (2020) The case for LGBT diversity and inclusion in sport business. Sport & Entertainment Review 5(1): 1-15.

- DeBiasse MS, Branham A, McFarland N (2022) Experiences of LGBTQ+ identifying students, interns and practitioners in dietetics. Critical Dietetics 6(2): 7-23.

- Eberman L, Nye E, Elder-Nye J (2023) Workplace climate for sexual and gender minorities in athletic training. Journal of Athletic Training 58(6S): S84-S85.

- Evans H, Trahsher A, Naff A (2022) Organizational and personal experiences of LGBTQ+ athletic trainers in clinical practice. Journal of Athletic Training 57(6S): S26-S27.

- Heiderscheit EA, Schlick CJ, Ellis RJ, Cheung EO, Lrizarry D, et al. (2022) Experiences of LGBTQ+ residents in US general surgery training programs. JAMA Surgery 157(1): 23-32.

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC (2015) Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology 56(1): 32-43.

- Huang YH, Villalobos K, Villaescusa N, Yamaguchi L (2020) Attitudes toward transgender individuals among OT students and practitioners. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 74(4S1): 7411510332p1.

- King M (2015) Attitudes of therapists and other health professionals toward their LGB patients. International Review of Psychiatry 27(5): 396-404.

- Landry J (2017) Delivering culturally sensitive care to LGBTQI patients. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 13(5): 342-347.

- Lim F, Johnson M, Eliason M (2015) A national survey of faculty knowledge, experience and readiness for teaching Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) health in baccalaureate nursing programs. Nursing Education Perspective 36: 144-152.

- Lu D, Pierce A, Jauregui J, Heron S, Lall MD, et al. (2020) Academic emergency medicine faculty experiences with racial and sexual discrimination. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 21(5): 1160-1169.

- Meyer IH, Russell ST, Hammack PL, Frost DM, Wilson BD (2021) Minority stress, distress and suicide attempts in three cohorts of sexual minority adults: A US probability sample. PLoS One 16(3): e024687.

- Mongelli F, Perrone D, Balducci J, Andrea S, Silvia F, et al. (2019) Minority stress and mental health among LGBT populations: An update of the evidence. Minerva Psichiatrica 60(1): 27-50.

- Munson EE, Ensign KA (2021) Transgender athletes experiences with health care in the athletic training setting. Journal of Athletic Training 56(1): 101-111.

- Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, Davidoff KC (2016) Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. The Journal of Sex Research 53(4-5): 488-508.

- Webster JR, Adams GA, Maranto CL, Sawyer K, Thoroughgood C (2018) Workplace contextual supports for LGBT employees: A review, meta-analysis, and agenda for future research. Human Resource Management 57(1): 193-210.

- Williams A, Thompson N, Kandola B (2022) Sexual orientation diversity and inclusion in the workplace: A qualitative study of LGB inclusion in a UK public sector organization. The Qualitative Report 27(4): 1068-1087.

- Wojcik H, Breslow AS, Fisher MR, Rodgers CR, Kibuszeski P, et al. (2022) Mental health disparities among sexual and gender minority frontline health care workers during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. LGBT Health 9(5): 359-367.

- Cage SA, Gallegos DM, Coulombe B, Warner BJ (2019) Clinical expert’s statement: The definition, prescription and application of cupping therapy. Clinical Practice in Athletic Training 2(2): 4-11.

- Maher T, Whyte M, Hoyles R, et al. (2015) Development of a consensus statement for the definition, diagnosis and treatment of acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis using the Delphi technique. Adv Ther 32(10): 929-943.

- Gonzalez CM, Grochowalski JH, Garba RJ, Bonner S, Marantz PR (2021) Validity evidence for a novel instrument assessing student attitudes toward instruction in implicit bias recognition and management. BMC Medical Education 21: 205.

© 2023 Cage SA. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)