- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Validity and Reliability of the Estonian Version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale

Tõnu Rätsep*, Maria Muuli and Diana Lippand

Department of Neurosurgery, Tartu University Hospital, Estonia

*Corresponding author: Tõnu Rätsep, Department of Neurosurgery, Tartu University Hospital, Tartu, Estonia

Submission: October 31, 2023;Published: November 15, 2023

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume8 Issue4

Abstract

Background: The readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale is designed to help the health care providers to determine patients’ discharge readiness and ensure efficient discharge planning. The aim of this study was to test the validity, reliability and psychometric properties of the Estonian version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form (RHDS/SF-Est).

Methods: The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the RHDS/SF into Estonian language followed international guidelines. The translation was pre-tested in a group of 30 patients. The content validity of the scale was evaluated by a panel of experts. The study population was 130 patients from the neurosurgical department. The internal consistency, construct validity, reproducibility and predictive validity of the scale was determined.

Results: The RHDS/SF-Est version scores ranged from 4,8-10,0 (mean 8,3). The Cronbach’s alpha of the whole scale was 0,84. The correlation matrix suggested that the four-dimensional structure of the original RHDS is appropriate for RHDS/SF-Est. Exploratory factor analysis supported the construct validity of the four-factor RHDS/SF in the Estonian cultural context. The model explained >85% of the total variance of the scale. The patients who lived alone, had cranial pathology and had not been operated upon had significantly lower RHDS/SF-Est values. Gender of the patients was the only significant predictor of post-discharge utilization of emergency health services in our patient group.

Conclusion: The RHDS/SF-Est is a reliable and valid scale for measuring discharge readiness of neurosurgical patients in Estonia. The scale could be used to identify potential discharge related problems and improve discharge planning.

Keywords:Readiness for hospital discharge scale; Reliability; Validity; Estonian

Abbreviations:RHDS: The Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale; RHDS/SF: The Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form; RHDS/SF-Est: The Estonian version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form

Introduction

Patient discharge preparation is necessary to ensure optimal transition from hospital to home. A hospital discharge is considered successful if there is increased quality of life, patient satisfaction and no readmission for the same illness within 6 weeks [1]. Readiness for discharge assessment has been identified as part of discharge preparation for every patient for efficient discharge planning processes [2]. The main goal of such assessment is to improve discharge preparation, reduce post discharge adverse events, improve the continuity of care and decrease emergent health care utilization [2-6]. Since the beginning of 1990s the Estonian health system has undergone comprehensive health reforms and the introduction of a new health care system based on family medicine has been recognized as a priority of health care policymakers. However, the healthcare system in Estonia is still hospital- and specialized medical care-centered and the coordination of patient management between the healthcare levels as well between the health and social care systems could be improved. It is evident that about one-sixth of the population lives alone; single-person households form the most numerous household type in present-day Estonia. Estonia, like many countries, is in the midst of epidemiological transition due to an aging population and the rise of chronic diseases, thus, it is critical to maintain and increase the quality, coordinated, comprehensive and continuous care of the patients [7].

Neurosurgical patients could be considered as high-risk patients for lower readiness for discharge because of possible neurological deficits, limiting their access to social care. Furthermore, neurosurgical pathology is not frequent and relatively unfamiliar for the family physicians and might lack professional guidance in post discharge care. Recently, Baksi et al., examined the readiness for discharge in 150 post craniotomy individuals and found that the patients had moderate levels of readiness for discharge and low levels of discharge-related knowledge [8]. Therefore, assessment of the readiness for hospital discharge is particularly important in this patient group. The Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale (RHDS), developed by Weiss and Piacentine [9,10], is the only scale that has been verified in several languages and in different population groups to measure patients’ perceptions of their readiness for discharge and improve identification of elevated readmission risk [11-15]. The English version of the RHDS has been used extensively but given the differences in terms of cultural and contextual factors, an Estonian version of the RHDS needs to be adapted and validated for the assessment of the readiness for discharge in Estonian language. Thus, the purpose of this study was: 1) to translate, adapt and validate the RHDS into Estonian language and assess the psychometric properties of the scale; 2) to use the scale for the evaluation of the perceptions of discharge readiness of neurosurgical patients.

Methods

The study population was 130 consecutive patients aged 18 or above who were treated and discharged from the department of neurosurgery of Tartu University hospital. We excluded patients who were transferred into another department or hospital and who were not able to understand the test because of cognitive or language problems. The scale was presented to the patients on the day of discharge. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (approval number 337/T-16). The formal verbal consent was obtained by all the members of the study group. The characteristics of the patients were collected from the patients or from the medical records. The RHDS was developed to measure patient perceptions of readiness for discharge from the hospital [9]. The RHDS/SF is the short form of a self-reported, 22-item instrument that consists of four subscales. The eight-item forms of the scale were derived by selecting two items from each subscale and the items are assessed on an 11-point scale (0–10), with high scores indicating greater readiness [10]. The subscales are as follows: (1) personal status, (2) knowledge, (3) coping ability and (4) expected support. Personal status measures how the patient feels on the day of discharge; knowledge measures patient’s knowledge about discharge information regarding selfmanagement at home; coping ability refers to how well the patient can actually manage the care demands at home; and expected support measures how much help and emotional support will be available to the patient after discharge [16]. The RHDS was scored by using a mean score (the sum of values for all completed items divided by the number of items answered). The subscale scores were similarly calculated.

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the RHDS/ SF followed international guidelines. The authors obtained permission from the scale developer (Dr. Weiss) to translate and validate the original RHDS/SF into Estonian language. Forward translation of the scales from English into Estonian was performed by two independent bilingual translators (a nurse and a physician), native speakers of Estonian language. The translations were then reviewed, compared and merged into a single forward translations by the translators. The back translations from Estonian into English were performed by an independent native English speaking translator, unfamiliar with the original instrument. Back translation review was performed by three bilingual experts with clinical and research experience. After that the back translations were submitted for evaluation to the author of the original versions and her suggestions were included into the translations of the instruments. The pre-testing of the Estonian version (RHDS/SFEst) was performed in 30 patients before discharge in order to check understandability, interpretation, and cultural relevance of the translation and test alternative wording. Two of the patients did not understand some questions and six patients suggested changes in the wording of the questions. The analysis showed that understanding of the following questions has occasionally been difficult: 2 – How would you describe your energy today?; 5 – How well will you be able to handle the demands of life at home?. The problematic questions were revised and rephrased to clarify their meaning in Estonian. Final decision about the content validity of the scale was performed by a panel of experts, including the translators and an individual experienced in the validation of instruments.

Emergency utilization of health services within 3 months postdischarge was evaluated through telephone interviews and hospital electronic information systems. The following occurrences were recorded into a single dichotomous variable (yes/no): hospital readmissions, urgent care/emergency room and family physicians visits. Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics for all measures. All continuous variables were checked for normality using Shapiro–Wilk’s W test. Statistical comparisons between groups for the continuous variables were conducted using t tests for independent samples. The internal consistency and reliability of scale was determined Cronbach’s α coefficients; value 0,7 or above was required to indicate acceptable relatedness of items. An item-analysis was performed to calculate intercorrelations between the items, the whole instrument and the factors by using Pearson correlations. Exploratory factor analyses was used to test the dimensionality and construct validity of the test via principal components analysis with promax rotation, while the number of factors that explained for >85% of total variance were retained. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and Barlett’s test of sphericity were also used to analyze the data. Reproducibility was tested using test-retest analysis by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient of the measured values at two separate time points (the second test was performed after two hours). Predictive validity was evaluated by logistic regression analysis to examine the effect of RHDS and patient characteristics to the likelihood of postdischarge utilization of emergency medical services. The data were analyzed using Statistica software (14.0.0.15 Tibco Software Inc.) and IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.1.1.(14). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

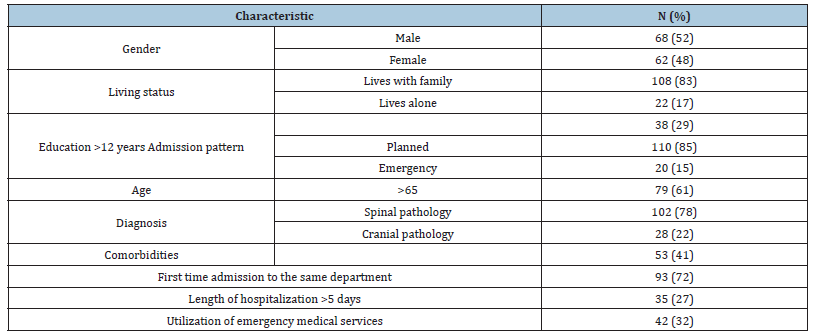

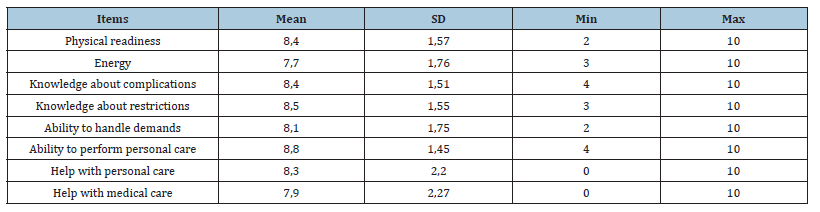

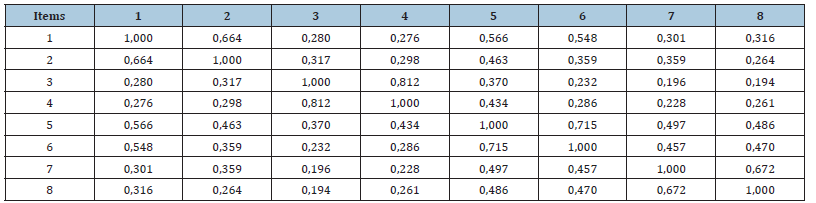

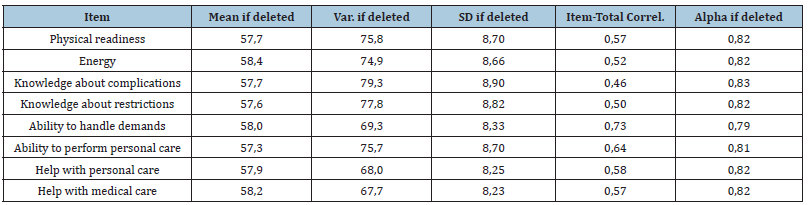

We prospectively collected data on 136 consecutive patients. Six of the questionnaires were incomplete (no response to at least three questions), thus responses from 130 patients were included in the analysis. 100 patients managed to complete the questionnaires twice. The characteristics of the patients and clinical variables are presented in Table 1. Participants’ age ranged from 18-81 years (mean 53,8 years). The length of hospitalization was 1-23 days (mean 5 days). Most of the patients were hospitalized because of spinal pathology (spinal stenosis, radiculopathy) and majority of the patients with cranial pathology had a tumor (14 patients) or traumatic brain injury (5 patients). Although 42 patients had used emergent medical services after discharge, only 3 patients had been readmitted to the hospital and only 7 patients had urgent care/ emergency room visits within 3 months post-discharge. The RHDS/ SF-Est scores ranged from 4,8-10,0. The descriptive statistics of the items are presented in Table 2. Item means varied from 7,9 to 8,8. The average item mean for the total scale was 8,3, and subscale item means ranged from 8.1 to 8.5. Item analyses were performed to assess the contribution of each item to the scale. The correlation matrix and item-total statistics are shown in Table 3 & 4. The correlation coefficients between all items were less than 0,90. The correlation matrix suggests that the four-dimensional structure of the original RHDS is appropriate for RHDS/SF-Est with items 1 and 2, items 3 and 4, items 5 and 6, and items 7 and 8 showing stronger relationships. The item-total statistics revealed no significant changes in means or variances of the whole scale when each item was deleted. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the whole scale (0,84) decreased when each item was deleted and all items were considered necessary for inclusion in the scale. For the subscales Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0,78-0,85.

Table 1:Patient characteristics.

Table 2:Descriptive statistics of the items of the RHDS/SF–Est.

RHDS/SF-Est: The Estonian version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form.

Table 3:Correlation matrix of items of the RHDS/SF–Est.

RHDS/SF-Est: The Estonian version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form.

Table 4:Item-total statistics of the RHDS/SF-Est.

Summary for scale: Mean=66,1 SD=9,7; Cronbach alpha: 0,84; Average inter-item correl.: 0,42

RHDS/SF-Est: The Estonian version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form.

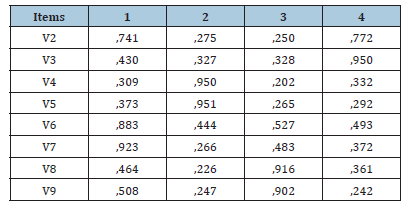

Table 5:Correlations Between Items and Factors of the

RHDS/SF-Est.

RHDS/SF-Est: The Estonian version of the Readiness for

Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form..

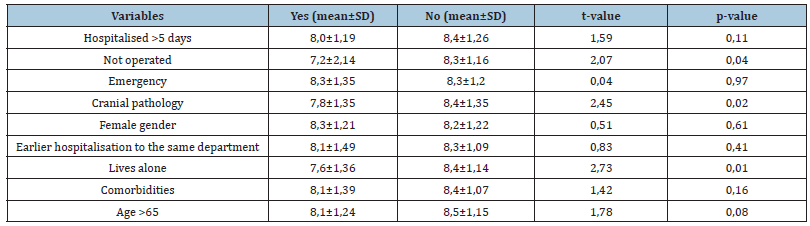

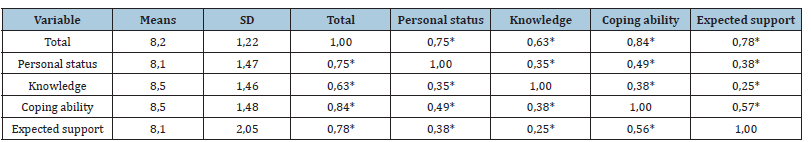

Exploratory factor analysis supported the construct validity of the four-factor RHDS/SF in the Estonian cultural context. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value (0,81) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (approx. chi-square= 497; p =<0,001) indicated that the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis. The results suggest that the scale has good structural validity, given the high loadings of the items on each factor. The four factors model explained 85% of the total variance of the scale (Table 5). Construct validity was further evaluated by analyzing the differences in discharge readiness scores between groups within the study sample. The relationship between patient characteristics and RHDS/SF-Est results is presented in Table 6. Variables ’lives alone’, ’cranial pathology’ and ’not operated’ were significantly related to the decreased RHDS/SF-Est values. Table 7 shows the correlations between the factors representing RHDS/SF-Est subscales and the total scale. All correlations were significant. Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicated low to moderate degrees of correlation between factor pairs (0,25-0,56) and higher correlation between subscale factors and the total scale (0,62-0,84). Reproducibility of the results of the RHDS-Est were assessed by correlation between the test and retest results in 104 patients and the retest results ranged from 3,9 to 10 (mean 8,5±1,24). High correlation (0,92) between the test and retest results showed excellent test-retest reproducibility. Eventually all the patient characteristics as well as RHDS/SF-Est results were included into the logistic regression analysis model. The model did not show significant relationships between the RHDS/SF-Est results and post-discharge utilization of emergency health services. Approximately twice as much male than female patients (28 vs. 14) had been looking for emergency medical care, which revealed gender as the only significant predictor of post-discharge utilization of emergency health services in our patient group.

The RHDS/SF-Est scores ranged from 4.8-10.0. The descriptive statistics of the items are presented in Table 2. Item means varied from 7.9 to 8.8. The average item mean for the total scale was 8.3, and subscale item means ranged from 8.1 to 8.5. Item analyses were performed to assess the contribution of each item to the scale. The correlation matrix and item-total statistics are shown in Table 3 & 4. The correlation coefficients between all items were less than .90. The correlation matrix suggests that the four-dimensional structure of the original RHDS is appropriate for RHDS/SF-Est with items 1 and 2, items 3 and 4, items 5 and 6, and items 7 and 8 showing stronger relationships. The item-total statistics revealed no significant changes in means or variances of the whole scale when each item was deleted. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the whole scale (.84) decreased when each item was deleted and all items were considered necessary for inclusion in the scale. For the subscales Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .78-.85. Exploratory factor analysis supported the construct validity of the four-factor RHDS/SF in the Estonian cultural context. The Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin value (.81) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (approx. chisquare = 497; p =<.001) indicated that the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis. The results suggest that the scale has good structural validity, given the high loadings of the items on each factor. The four factors model explained 85% of the total variance of the scale (Table 5). Construct validity was further evaluated by analyzing the differences in discharge readiness scores between groups within the study sample. The relationship between patient characteristics and RHDS/SF-Est results is presented in Table 6. Variables ’lives alone’, ’cranial pathology’ and ’not operated’ were significantly related to the decreased RHDS/SF-Est values. Table 7 shows the correlations between the factors representing RHDS/SFEst subscales and the total scale. Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicated low to moderate degrees of correlation between factor pairs (.25-.56) and higher correlation between subscale factors and the total scale (.62-.84). Reproducibility of the results of the RHDS/ SF-Est were assessed by correlation between the test and retest results in 104 patients and the retest results ranged from 3.9 to 10 (mean 8.5±1.24). High correlation (.92) between the test and retest results showed excellent test-retest reproducibility.

Table 6:Relationship between patient characteristics and RHDS/SF-Est results.

RHDS/SF-Est: the Estonian version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale/Short Form.

Table 7:Factor and item correlation.

Marked correlations are significant at p < ,05.

Discussion

In the present study, cultural adaptation of the Estonian version of the RHDS/SF was performed and psychometric features of the test were established in neurosurgical patients. The results of the study indicate that the structure of the RHDS/SF-Est is similar to the original version and the scale is a reliable and valid instrument for use in the evaluated group of patients. We found that the fourfactor RHDS/SF-Est, including personal status, knowledge, coping ability, and expected support subscales, is appropriate to use in the Estonian cultural context. The earlier translations and adaptations of the RHDS has resulted in different factor structures or removal of items from the original scale [13,15]. The RHDS/SF has been translated into Turkish language and, similarly to our results, the original four-factor structure has been possible to maintainthe four factors explained 87.6% of the total variance [12]. The internal consistency and global score of the RHDS/SF-Est were also comparable to the original English version [9,10]. The subscales with the highest mean scores were knowledge and coping ability, and the lowest scores were obtained for expected support and personal status. Analogous scores have been described before [9,13], however, Zhao et al. [15] found the highest mean item scores for expected support subscales and lowest for personal status [15] and Kaya et al. [12] revealed the lowest scores for knowledge and the highest for personal status items [12]. Several factors may help to explain these differences: cultural dissimilarities, local customs, different population groups or even differences in the healthcare system and reimbursement policy have been referred as potential contributors [11-15].

The patients with cranial pathology had lower RHDS/SF-Est scores in our study. As far as we know, there have been no studies adapting the RHDS for neurosurgical patients. Post craniotomy patients’ readiness for discharge was examined by Baksi et al. [8], who described that the individuals’ age, employment status, presence of a person to provide care at home, poor financial status, and first hospitalization during the lifetime of the patient were statistically significant predictors of their readiness for discharge [8]. The evaluation of discharge readiness in neurosurgical patients is important, and appropriate test must be suitable to evaluate both cranial and spinal patients. We had representatives from both diagnostic groups in our study and both groups participated in the pre-testing and validation of the test. The patients who were not able to understand the test because of cognitive deficits, were excluded from the study, however, proper cognitive testing was not performed. Cranial pathology is generally more frightening and unfamiliar to family physicians as well as social workers and our results confirm that the RHDS/SF-Est would be useful for assessing the discharge readiness of neurosurgical patients. Similarly, to the original study, no significant relationship was found between RHDS/SF-Est scores and emergent utilization of health services after discharge [9]. The fact may be due to relatively small patient group and small readmission rate, however, Weiss et al. [10,16] have demonstrated that nurse assessment of discharge readiness could facilitate identification of patients at risk for readmission or emergency department utilization [10,16]. Further studies should compare the self-ratings of patients with the ratings assigned by nurses, which might have potential to improve the evaluation of the readiness of discharge in neurosurgical patients.

Conclusion

The RHDS/SF-Est is a reliable and valid scale for measuring discharge readiness of neurosurgical patients and could be used to identify potential discharge related problems and improve discharge planning. However, more studies are needed on different and larger patient populations to confirm our findings and examine the relationships between RHDS/SF-Est results and utilization of emergency medical services after discharge The limitations of this study is the collection of data from only one hospital and one specialty, which may compromise the representativeness of the sample population. Hopefully the scale is useful to help healthcare professionals to implement interventions necessary to prevent post discharge complications, reduce hospital readmission rates and increase post discharge quality of life.

References

- Carroll A, Dowling M (2007) Discharge planning: Communication, education and patient participation. British Journal of Nursing 16(14): 882-886.

- Weiss ME, Piacentine LB, Lokken L, Ancona J, Archer J, et al. (2007) Perceived readiness for hospital discharge in adult medical-surgical patients. Clin Nurse Spec 21(1): 31-42.

- Coffey A, McCarthy GM (2013) Older people’s perception of their readiness for discharge and post-discharge use of community support and services. International Journal of Older People Nursing 8(2): 104-115.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW (2003) The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Annals of Internal Medicine 138(3): 161-167.

- Galvin EC, Wills T, Coffey A (2017) Readiness for hospital discharge: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 73(11): 2547-2557.

- Mixon AS, Goggins K, Bell SP, Vasilevskis EE, Nwosu S, et al. (2016) Preparedness for hospital discharge and prediction of readmission. J Hosp Med 11(9): 603-609.

- Põlluste K, Lember M (2016) Primary health care in Estonia. Fam Med Prim Care Rev 18: 74-77.

- Baksi A, Arda SH, Inal G (2020) Postcraniotomy patients' readiness for discharge and predictors of their readiness for discharge. J Neurosci Nurs 52(6): 295-299.

- Weiss ME, Piacentine LB (2006) Psychometric properties of the readiness for hospital discharge scale. J Nurs Meas 14(3): 163-80.

- Weiss ME, Costa LL, Yakusheva O, Bobay KL (2014) Validation of patient and nurse short forms of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale and their relationship to return to the hospital. Health Serv Res 49(1): 304-317.

- Aldughmi O, Bobay KL, Bekhet AK, Sedgewick G, Weiss ME (2021) Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometrics evaluation of the Arabic version of the patient-readiness for hospital discharge Scale. J Nurs Meas 13: JNM-D-20-00066.

- Kaya S, Sain Guven G, Teleş M, Korku C, Aydan S, et al. (2018) Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the readiness for hospital discharge scale/short form. J Nurs Manag 26(3): 295-301.

- Mabire C, Lecerf T, Büla C, Morin D, Blanc G, et al. (2015) Translation and psychometric evaluation of a French version of the Readiness for Hospital Discharge Scale. J Clin Nurs 24(19-20): 2983-2992.

- Siqueira TH, Vila VDSC, Weiss ME (2018) Cross-cultural adaptation of the instrument readiness for hospital discharge scale-adult form. Rev Bras Enferm 71(3): 983-991.

- Zhao H, Feng X, Yu R, Gu D, Ji X (2016) Validation of the Chinese version of the readiness for hospital discharge scale on patients who have undergone laryngectomy. J Nurs Res 24(4): 321-328.

- Weiss M, Yakusheva O, Bobay K (2010) Nurse and patient perceptions of discharge readiness in relation to postdischarge utilization. Med Care 48(5): 482-486.

© 2023 Tõnu Rätsep. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)