- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Prevalence of Chronic Low Back Pain and Associated Risk Factors in Healthcare Workers during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Selin Ozen1* and Eda Cakmak2

1Department of Physical Therapy, Baskent University Faculty of Medicine, Turkey

2Department of Audiology, Baskent University Faculty of Health Sciences, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Selin Ozen, Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Baskent University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

Submission: October 11, 2021;Published: December 01, 2021

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume7 Issue5

Abstract

Objectives: To establish the prevalence and severity of chronic low back pain (CLBP) in hospital-based healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic and identify associated risk factors.

Design: A cross sectional, self - survey study.

Place & duration of study: A university hospital in Turkey between May 2020 and December 2020.

Methodology: Healthcare workers between the ages of 18-65 were questioned regarding the presence of CLBP and related factors. Those reporting CLBP also completed a visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain, Roland - Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) and the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP).

Result: 120 physicians, 119 nurses, 70 caregivers, 63 secretarial staff and 57 allied health workers were included in the study. Mean age was 35.27 ± 9.70 years. 65.64% had CLBP, most prevalent in nurses (32.4%). Body mass index was higher and time spent at work longer in those with CLBP (25.21 4.07, p=0.047. OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.01 - 1.13 and 10.1 2.56, p=0.001. OR 1.19, CI 1.08 - 1.31 respectively). 57.5% reported an exacerbation of CLBP during the Covid-19 pandemic with an average increase of 10.2 14.14%. NHP part 1 (189.98 137.69) and part 2 scores (1.90 1.97) were highest in the caregivers. RMDQ scores were highest in the secretarial staff (10.62 5.89).

Conclusion: CLBP was present in the majority of health workers, most experienced an exacerbation in symptoms during the Covid-19 pandemic. Future studies could investigate the frequency of a wider range of possible occupational musculoskeletal problems in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic so to identify and suggest treatment strategies for the most common problems.

Keywords:SARS-CoV-2; Pandemics; Health personnel

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a commonly occurring health problem with a reported worldwide prevalence and incidence of up to 20% and 7% respectively. In Turkey, the lifetime prevalence of LBP has been identified as 51% and that of chronic low back pain (CLBP) 13.1%. Low back pain can be defined as activity limiting pain in the lower back, which may or may not be referred to the legs of at least one day’s duration. In chronic low back pain (CLBP), the pain persists for more than three months. Personal, occupational and psychosocial risk factors for the development of back pain include age, gender, increased body mass index (BMI), heavy lifting, sitting stationary for long periods of time and low mood [1].

Healthcare workers are an occupational group who are highly exposed to both the occupational and psychosocial risk factors associated with LBP. In one study, the lifelong prevalence of LBP in health workers of a state hospital in Turkey was identified as 53% with a point prevalence of 29.5% and was especially associated with personal and occupational factors. Furthermore, it is entirely conceivable that this occupational group has been exposed to the heightened physical and psychosocial stresses of working in a hospital during the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic which, in turn, may have had an adverse impact on the severity of LBP [2-6].

The aims of this study were to establish the prevalence and severity of CLBP in hospital based healthcare workers and personnel and identify risk factors associated with CLBP during the Covid-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that the severity of CLBP in healthcare workers had increased during the months of the Covid- 19 pandemic [7].

Methodology

A cross sectional, self- survey study of healthcare workers and hospital personnel of a university hospital in Ankara, Turkey conducted between May 2020 and December 2020. All hospital personnel between the ages of 18 and 65 who were willing to participate in the study were assessed for study inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: a previous diagnosis of inflammatory arthropathy, spondyloarthropathy, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia syndrome, nephrolithiasis, uterine fibroids, malignancy, those who had been pregnant over the past year or had undergone surgery involving the back [8-11].

Hospital personnel were reached and informed of the study by conducting departmental visits on three separate occasions after which the questionnaire was distributed via the intrahospital email system. It was stressed to staff that participation was of value to the study whether or not they suffered from CLBP and that all surveys would be completed anonymously. Study participants who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were asked to complete a questionnaire containing details regarding their demographic characteristics, details of their role in the hospital, mode of transport to and from work, time spent at work, job satisfaction and past medical history [12-15]. The study participants were then questioned regarding the presence of CLBP which was defined as persistent pain in the lower back lasting for more than three months which was of a mechanical nature, worse on movement and improved with rest. The severity of the CLBP was graded using a visual analogue scale for pain (VAS). The VAS is a reliable scale used to register the intensity of chronic pain where 0cm signifies no pain and 10cm the worst pain imaginable. Those who had chronic LBP were also questioned on whether the onset of LBP preceded the Covid-19 pandemic, and whether the severity of the LBP had increased during the pandemic [16-18].

Finally, those with chronic LBP were asked to complete the Roland - Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) and the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP). The RMDQ was designed to measure selfrated disability due to back pain and questions the effect of back pain on 24 different activities of daily living (ADL); the validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the RMDQ has been shown. The patient receives one point for every ADL on which back pain has had a detrimental effect and obtains a final score between 0-24. The greater the score, the greater the patient’s disability due to back pain. The NHP is used as a measure of perceived health problems and is widely used in those with musculoskeletal impairments and chronic disability and has been adapted into Turkish. , Part one of the profile is comprised of Thirty-Eight questions which reflect health problems in six areas: sleep, physical mobility, energy, pain, emotional reactions and social isolation. The individual receives a score between 0-600 for this part of the profile, the higher the score the greater the problem. Part 2 questions the impact of the person’s health problems in seven different areas of daily life most often affected by health; the patient receives one score (giving a total between 0-7) for each area which has been negatively impacted by their health problems [19,20].

The study obtained ethical approval Study approval was obtained from the XXX University Review Board (project no.KA20/80) and carried out according to institutional guidelines and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to study commencement.

Statistical analysis

The total number of healthcare workers in the hospital was 1581. In order to obtain a study power of 95% with a 5% type 1 error, a total of 305 healthcare workers were to be recruited to the study. Recruitment of study participants was performed using stratified random sampling. Strata and participant numbers according to the power analysis consisted of a minimum of 104 physicians, 71 nurses, 41 allied health professionals (physiotherapists and technicians), 54 caregivers and 35 secretarial staff.

Data was analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data was expressed in numbers, percentages, mean and standard deviations, median and 25th and 75th percentiles. Normal distribution of data was determined using the Kolmogorov- Smirnov test. Pearson’s Chi-Square test was used when comparing independent categorical data. Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal- Wallis variance analysis tests were used to analyse quantitative data. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to determine risk factors for back pain. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

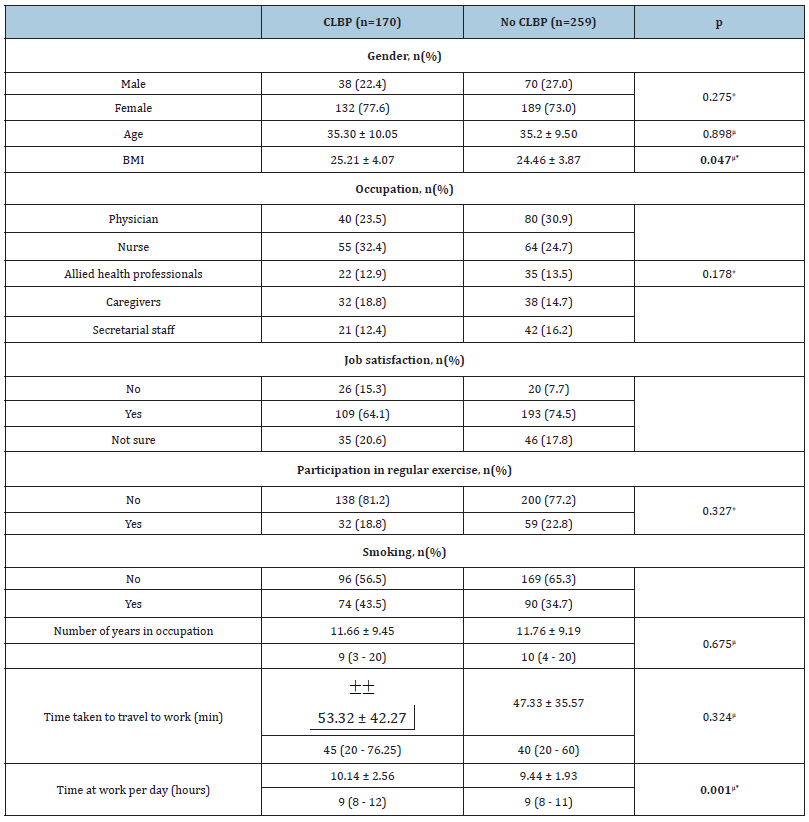

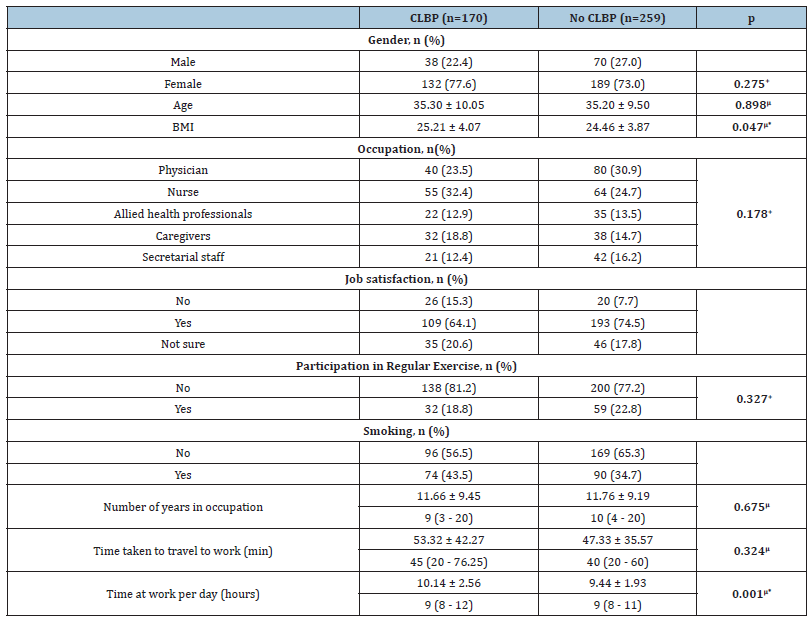

A total of 429 out of 472 healthcare workers met the inclusionexclusion criteria and participated in the study. All completed the entirety of the survey. The participants consisted of 120 physicians, 119 nurses, 70 caregivers, 63 secretarial staff and 57 allied health workers (physiotherapists, health technicians). Of the study participants, 108 (25.2%) were male and 321 (74.8%) were female. Average age of all study participants was 35.27 ± 9.70 years. Chronic low back pain was present in 65.64% of the study population. The BMI of those with CLBP was 25.21 4.07 and 24.46 3.87 in those without CLBP (p=0.047). Chronic low back pain was most prevalent in nurses (32.4%). 81.2% of those with CLBP did not participate in regular exercise, however this was also the case in those without LBP (77.2%, p=0.327). Time spent at work was significantly longer in those with CLBP, 10.1 2.56 (p=0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1:Demographics and clinical data of study participants.

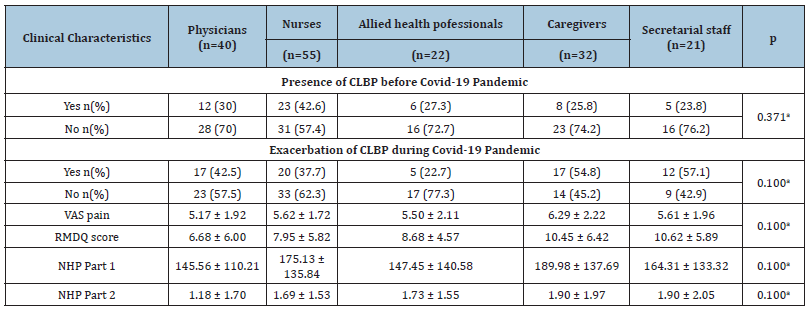

CLBP: chronic low back pain, mean ± standard deviation, median (25th to 75th percentile),+Pearson Chi-Square Test, μMann-Whitney U Test, *p<0.05.

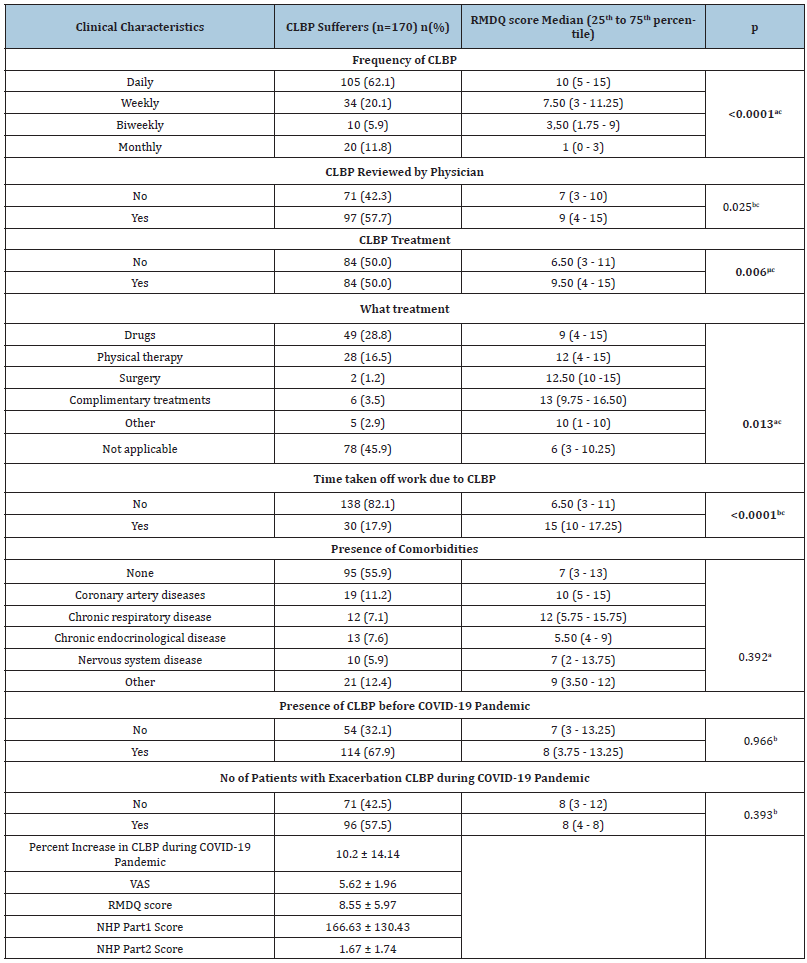

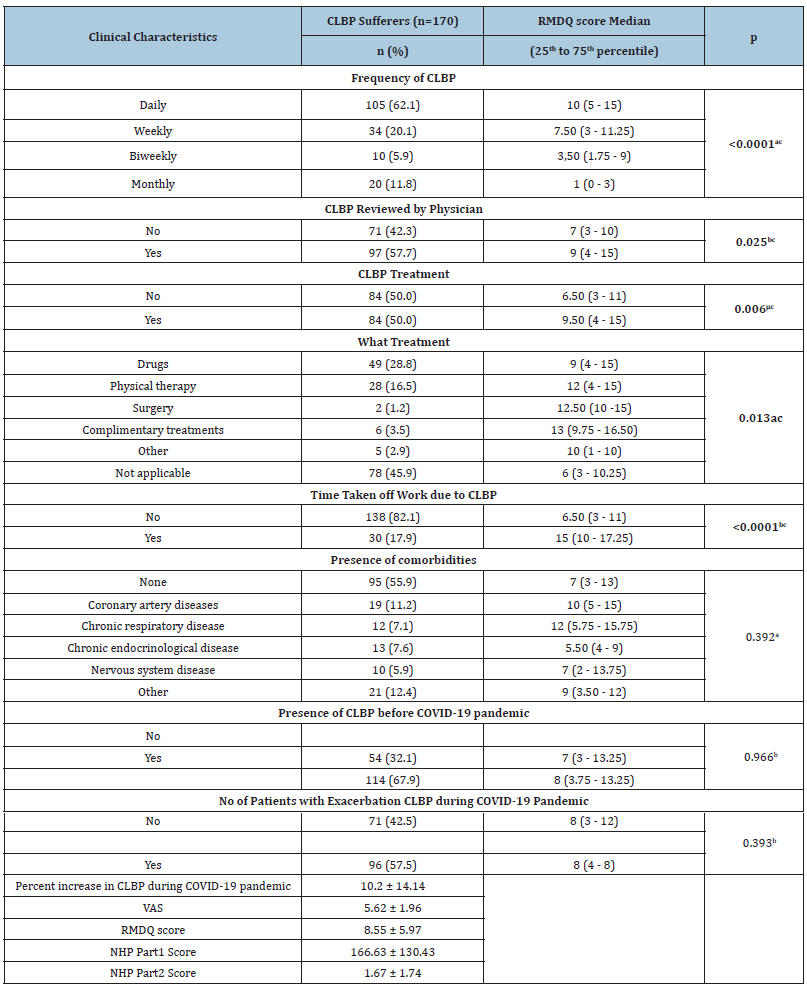

In those reporting CLBP, the mean VAS for LBP was 5.62 1.96, the mean Roland Morris score was 8.55 5.97, the mean NHP part 1 score was 166.63 130.43 and part 2 score 1.67 1.74 (Table 2). RMDQ scores were significantly higher in those with daily complaints of LBP (p<0.0001), those who had required evaluation by a physician (p=0.025) and medical treatment (p=0.006) and those who had taken time off work (p=<0.0001) (Table 2). When the clinical characteristics were analyzed according to the participants’ occupations, VAS for CLBP (6.29 2.22), NHP part 1 (189.98 137.69) and part 2 scores (1.90 1.97) were highest in the caregivers. RMDQ scores were highest in the secretarial staff (10.62 5.89) and caregivers (10.45 6.42) (Table 3).

Table 2:Demographics and clinical data of study participants.

CLBP: chronic low back pain, RMDQ: Roland - Morris Disability Questionnaire, NHP: Nottingham Health Profile, median (25th to 75th percentile) for RMDQ Score, aKruskal-Wallis Test, bMann-Whitney U Test, cp<0.05

The majority of the participants with CLBP (67.9%), and the majority of each occupational group, had complaints of CLBP prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Overall, 57.5% of those with CLBP reported an exacerbation of symptoms during the Covid-19 pandemic. This exacerbation occurred in the majority of physicians, nurses and allied health professionals with a history of CLBP. The average increase in CLBP symptoms reported by the patients during this period was 10.2 14.14% (Table 3).

Table 3:Clinical characteristics of study participants with chronic low back pain according to occupation.

aPearson Chi-Square Test, CLBP: chronic low back pain, RMDQ: Roland - Morris Disability Questionnaire, NHP: Nottingham Health Profile

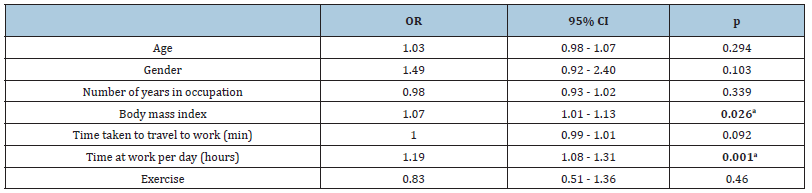

Body mass index and time spent at work were significant risk factors for CLBP (Table 4). Every 1kg/m2 increase in BMI increased the risk of CLBP by 1.07 (p=0.026) and ever 1 hour increase in time spent at work increased the risk of CLBP by 1.19 (p=0.001).

Table 4:Logistic regression model of risk factors for chronic low back pain.

OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, ap<0.05

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which focuses on the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on CLBP in hospital based health care workers. Even though adverse psychological outcomes and physical symptoms in health workers during the covid-19 pandemic have been studied, musculoskeletal complaints have not been addressed. The results of this study showed that CLBP was most prevalent amongst nurses. Equally, caregivers had the highest level of pain and highest level of perceived health problems according to the VAS and NHP respectively (Table 5). According to the RMDQ, disability due to LBP was most in the secretarial staff and caregivers. In addition, even though most of the study participants with CLBP had a history of CLBP prior to the onset of the pandemic, complaints of LBP increased in the majority during the pandemic. This was especially true for physicians, nurses and the allied health professionals such as physiotherapists and technicians. Increased BMI and longer working hours seem to increase the risk of CLBP (Table 6).

Similarly to the findings of this study, a previous study on LBP in healthcare workers in Turkey found that factors such as high BMI and working for longer hours were associated with an increased risk of LBP.6 Advanced age, female sex and low job satisfaction were amongst other factors identified.6 The high prevalence of CLBP (65.64%) in our study amongst healthcare professionals, and especially amongst nursing staff, is in keeping with previous studies conducted in various different parts of the world.

Table 5:Demographics and clinical data of study participants.

CLBP: chronic low back pain, mean ± standard deviation, median (25th to 75th percentile), +Pearson Chi-Square Test, μMann-Whitney U Test, *p<0.05

Table 6:Clinical characteristics of study participants with chronic low back pain.

CLBP: chronic low back pain, RMDQ: Roland - Morris Disability Questionnaire, NHP: Nottingham Health Profile, median (25th to 75th percentile) for RMDQ Score, aKruskal-Wallis Test, bMann-Whitney U Test, cp<0.05

Studies have also identified increased levels of heavy lifting and the number of daily lifts/transfers, as risk factors for LBP. , In our study, even though occupational heavy lifting was not directly questioned as a risk factor for LBP, the level of LBP determined using the VAS, the RMDQ for self-determined level of disability were highest in the caregivers who are also the members of staff most involved in lifting and transfer of patients. Moreover, the NHP scores which reflect the individual’s perception of health problems, pain, emotional wellbeing, ability to perform activities of daily living and quality of life, were poorest amongst caregivers (Table 7).

Table 7:Clinical characteristics of study participants with chronic low back pain according to occupation.

Despite the majority of study participants having a history of CLBP prior to the covid-19 pandemic, most (57.5%) also reported on average a 10.2% increase in CLBP symptoms during the Covid-19 pandemic. Over half of the physicians, nurses and allied health professionals reported an exacerbation of LBP symptoms during the Covid-19 pandemic. This does not come as a surprise as work stress levels is a known risk factor for LBP.15,16 During the Covid-19 pandemic (Table 8), front line healthcare workers especially have experienced an increase in workload, the persistent threat of infection to themselves and their families and the worries of shortages in personal protective equipment. Bearing this in mind, a study on the impact of Covid-19 on physician stress and mental health in the first few months of the pandemic, found that levels of stress were highest in hospital physicians, in all stages of their careers, and especially in those working in critical care and emergency departments. Another study conducted in China recorded depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress in up to 71.5% of health workers during the Covid-19 pandemic; mental health was worst in nurses and frontline healthcare workers.

Table 8:Logistic regression model of risk factors for chronic low back pain.

OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, ap<0.05.

The strong aspects of this study include: study participants completing all parts of the survey, validated tools such as the RMDQ and NHP being used in the evaluation of disability due to back pain and perceived health related problems. Limitations of the study included that the NHP was not completed by those without LBP. Therefore, no comparison of health-related issues could be made between those with and without CLBP. In addition, it would have been interesting to know how many participants had contracted Covid-19 as this maybe one factor affecting the presence of CLBP and its severity.

Conclusion

CLBP was present in the majority of the study population and most experienced an exacerbation of CLBP during the Covid-19 pandemic. We believe that health workers of other hospitals, both nationally and internationally, will have had similar experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic due to the frontline nature of the work and stressors involved. Future studies could investigate the frequency of a wider range of possible occupational musculoskeletal problems in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic so to identify and suggest treatment strategies for the most common problems.

References

- Fatoye F, Gebrye T, Odeyemi I (2019) Real-world incidence and prevalence of low back pain using routinely collected data. Rheumatol Int 39(4): 619-626.

- Altinel L, Kose KC, Ergan V, Isik C, Aksoy Y, et al. (2008) The prevalence of low back pain and risk factors among adult population in Afyon region, Turkey. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 42(5): 328-333.

- Hoy DG, March L, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, et al. (2010) Measuring the global burden of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24(2): 155-165.

- Rozenberg S (2008) Chronic low back pain, definition and management [Chronic low back pain: definition and treatment]. Rev Prat 58(3): 265-272.

- Govindu NK, Babski RK (2014) Effects of personal, psychosocial and occupational factors on low back pain severity in workers. Int J Ind Ergon 44(2): 335-341.

- Şimşek Ş, Yağci N, Şenol H (2017) Prevalence of and risk factors for low back pain among healthcare workers in Denizli. Agri 29(2): 71-78.

- Joyce CRB, Zutshi DW, Hrubes V, Mason RM (1975) Comparison of fixed interval and visual analogue scales for rating chronic pain. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 8(6): 415-420.

- Roland M, Morris R (1983) A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low back pain. Spine 8(2): 142-144.

- Küçükdeveci AA, Tennant A, Elhan AH, Niyazoglu H (2001) Validation of the Turkish version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for use in low back pain. Spine 26(24): 2738-2743.

- Shunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SR (1985) Measuring health status: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 35(273): 185-188.

- Kucukdeveci AA, Mckenna SP, Kutlay S, Gursel Y, Whalley D, et al. (2000) The development and psychometric assessment of the Turkish version of the Nottingham Health Profile. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 23(1): 31-38.

- Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, et al. (2020) A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 88: 559-565.

- Bos E, Krol B, van der Star L, Groothoff J (2007) Risk factors and musculoskeletal complaints in non-specialized nurses, IC nurses, operation room nurses, and X-ray technologists. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 80(3): 198-206.

- Omokhodion FO, Umar US, Ogunnowo BE (2000) Prevalence of low back pain among staff in a rural hospital in Nigeria. Occupational Medicine 50(2): 107-110.

- Corona G, Amedei F, Miselli F, Padalino MP, Tibaldi S (2005) Association between relational and organizational factors and occurrence of musculoskeletal disease in health personnel. Giornale italiano di medicina del lavoro ed ergonomia 27(2): 208-212.

- Karahan A, Kav S, Abbasoglu A, Dogan N (2009) Low back pain: prevalence and associated risk factors among hospital staff. J Adv Nurs 65(3): 516-524.

- Wong TS, Teo N, Kyaw MO (2010) Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Low Back Pain Among Health Care Providers in a District Hospital. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal 4(2): 2-28.

- Landry MD, Raman SR, Sulway C, Golightly YM, Hamdan E (2008) Prevalence and risk factors associated with low back pain among health care providers in a Kuwait hospital. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33(5): 539-545.

- Linzerm, Stillman M, Brown R, Taylor S, Nankivil N, et al. (2021) Preliminary Report: US Physician Stress During the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations. Quality & Outcomes 5(1): 127-136.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, et al. (2019) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3(3): e203976.

© 2021 Selin Ozen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)