- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Civilian and Part-Time Services Health Care Professionals’ Reactions to Military Roles During Deployment to The Gulf War (1991)

Deidre Wild*

Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, UK

*Corresponding author: Deidre Wild, Senior Research Fellow (Hon), Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, Coventry, UK

Submission: August 10, 2020Published: December 04, 2020

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume6 Issue5

Abstract

Six months after the end of the Gulf War, 95 non-Regular Services health care professionals called-up and volunteers were recruited opportunistically to a study of their social, psychological and health reactions to the experiences from participation in this event. This part of the study focusses upon their reactions to and expectations of pre-departure mobilization and their subsequent deployment in the Gulf. During pre-deployment anticipatory fear was expressed often with excitement at the prospect of going to war. The reality of war, once they had arrived in the Gulf was of a different and more intense fear than before departure and some tried hard to disguise this emotion in order to not be seen as weak. Fear was not the most difficult aspect coped with during deployment, rather inter-military disharmony between the three groups of Reservists, those in the TA and Regular soldiers was identified as being the most difficult Some Reservists blamed their late arrival in the Gulf as a cause of feeling ‘outsiders’ to ‘in’ groups, while those in the TA complained that their rank was disrespected by Regulars’. Poor management by senior command officers was often blamed for not taking action to resolve this problem. Reservists were found to have the most difficult time in the Gulf perhaps because their expectations of Regulars in particular was that the latter were not as able as they were when in full time service.

Keywords: Gulf war; Health care professionals; Reservists; Pre deployment; Deployment

Background Literature

The pre-war invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990 prompted United Nations’ condemnation followed by a trade ban. World-wide concerns were raised by Iraq's potential to further destabilise the Middle East (ongoing tensions already existed between some Arab states with Israel); the hostage-taking of foreign nationals in Iraq as a ‘human shield’; the inhumane treatment of the Kuwaiti population under Iraqi occupation, and economic issues related to Iraq’s annexing of Kuwaiti oil facilities [1]. The major anticipatory threat posed by Iraq was its capability to use biological and chemical weaponry agents [2], supported by the means for their long-range delivery [3]. To date, the GW of 1990-91 remains the only multi-national modern war in which troops have been militarily prepared for this threat.

In November 1990, in response to the size of the Iraqi threat combined with the potential insufficiency in the number of Regular-serving military medical personnel available for casualty care, part-time military Voluntary Services (VS) male and female health professionals (doctors, nurses, and other professions allied to medicine [PAMS] were invited to volunteer [3]. Although some VS personnel responded positively to the request, the number was insufficient and consequentially those on the Reserve List (ex-Regular Services personnel who had left or retired from the military) were called-up. Such action had not been undertaken since the Korean War [4]. Many of these non-Regular services personnel arrived in Saudi Arabia in January 1991, just before or during the Coalition’s intense air offensive (Operation Desert Storm) [4]. It was also when Iraq released SCUD missile attacks on both Saudi Arabia and Israel [3].

The Health Professional Veterans' (HPVs)’ reactions to their particular entry route either as a volunteer Reservist or member of the VS Territorial Army (TA) or having been a Reservist called-up to the GW were full of anticipatory and anticipated emotions at the prospect of going to war. Plutchik & Kellerman [5] define and map individual emotions as ‘hypothetical states’. However, for the purpose of understanding the HPVs’ emotional reactions over the fastchanging context of the GW, the approach of Ortony & Turner [6] has been adopted. This recommends articulation of the ways in which people appraise their responses to a situation, rather than the identification of emotions as entities.

In addition, other authors [7] make a distinction between two forms of future-orientated emotional responses based upon anticipation being relevant to the process of appraisal. They describe responses as being either ‘anticipatory’ (from consideration of the uncertain and unknown elements of future events), or ‘anticipated’ (arising from the event being imagined prior to it happening) with a greater sense of control over an imaginary situation where there is some certainty of outcome than in one where there is high uncertainty (as in going to war).

Fear as a primary emotion has physiological, behavioural and social dimensions [8] and is a part of a complexity of reactions and feelings, including panic, dread, anxiety, despair, caution, and cowardliness [7] Other experimental work differentiate types of fear and its emotional and physiological responses as either imaginary or real with physiological and emotional adaptive differences between them [9]. Several authors suggest that the threatened use of biochemical and/or biological agents as an unconventional form of weaponry is likely to raise the greatest fear in troops, no less because it makes no distinction in its contaminating effects between combatants and non-combatants [10-12]. Such fear is reported in the publications of personal accounts of some British GW veterans [13,14]; in a study of UK troops during GW deployment training to counter this type of attack [15], and in a US review of GW stressors [16].

Some years after the GW, several authors argue [17-19] that participating in war is not only a test of military skills but also of the self-worth of the individual as the warrior. As such, the stressors encountered (and even more so those overcome) are essential to this process [17]. The commitment of the British military, in particular, to the concept of ‘the ancient warrior-type’ is a recurrent theme that is woven into the war-related written texts of many respected authors [20-23].

Although the study's participants were medical and in other professions allied to it, they also were trained soldiers. Most were attached to field and general military hospitals that had already been set-up or were in the process of being completed. As such, this necessitated joining established groups of Regulars. Hogg & Reid [24] suggest that the desire to ‘belong’ to groups is a form of social categorization linked to the concept of self. Once inside the group, the member is able to predict his/her own and other persons’ behaviors in order to feel protected and cope with uncertainty. Comfort is derived from efficient planning and knowing how to feel and behave. These features are important determinants of group cohesion upon which, the military places great store [25] and within this context, the reactions of the present study's participants towards entry to new military groups are considered.

Methodology

Design

Using a predominately prospective longitudinal design comprising three six monthly postal questionnaire surveys, the data included in this article were collected in the first questionnaire issued some six months after the War’s end. A small pilot study preceded the main study to refine the materials and agree the first and subsequent follow up questionnaires' content.

Materials

The first questionnaire contained a series of related closed and open questions. This ‘mix’ of quantitative and qualitative inquiry sought to enable a greater depth of understanding of the HPVs’ experiences than either method when employed alone [26].

Sample recruitment procedure

A GW nurse veteran known to the author acted as an intermediary by contacting and informing 73 veterans of GW who had returned with her from the Gulf as one planeload about the study, (at this time, only she held their addresses) From this, the first 57 HPVs (47 Reservists and 10 Territorial Army [TA] personnel) gave consent to receive questionnaires. The first TA participants were asked to facilitate requests to other similar TA GW HPV volunteers to join the study and 33 agreed. Finally, five Welfare Officers from the Order of St John of Jerusalem joined the study having heard of it via a press release. The final sample comprised 47 Reservists (26 called-up and 21 volunteers); 43 volunteer TA, and 5 volunteer Welfare Officers.

Mode of analysis

Qualitative data in the form of the HPVs’ comments were examined first by two researchers independently identifying and categorising key words or phrases. The phrase labels produced captured as closely as possible the meaning of the HPVs’ original words or phrases. This thematic content analysis has been described by several authors [27,28]. The two researchers then made cross comparisons (and when necessary re-examined the data) to reach consensus. In some instances, the qualitative data were transformed into new variables to permit the use of descriptive statistics. In these instances, quantitative data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and logistic regression with a forward stepwise Wald was used as the main predictive test.

Ethical consideration

Although the principles adhered to early in 1991 preceded the formal ethical requirements for today’s research, the general principles of doing no harm; securing informed consent; the acceptance of autonomy over compliance, and respect for rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality [29] were upheld throughout the research. Authoritative military and academic advice were taken throughout the study to avoid potentially sensitive issues in the materials. All information forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data were -held securely and in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in 1998.

Result

Characteristics of the participant sample

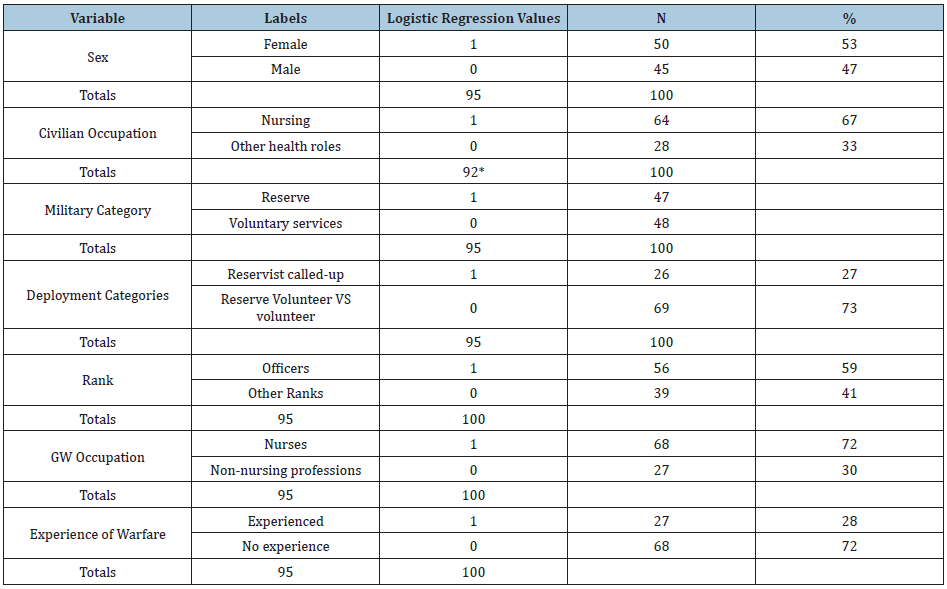

As shown in Table 1, the personal, professional and military characteristic of the HPVs were formatted mainly as dichotomous independent variables (IVS) each with the values of 0 and 1 (value of interest) to facilitate logistic regression. The HPVs’ ages ranged from 23 to 53 years (mean=37; SD=8.59; median=35). When the figures for the civilian occupations of the 95 HPVs were cross tabulated with their qualifications, 67 of the 68 held nursing qualifications (1 missing) and of these, 49 (73%) worked as Registered General Nurses; 4 (6%) as Registered Mental Nurses, and the remaining 14 (21%) were State Enrolled Nurses

All of the health professionals (nurses, doctors, physiotherapists, etc.), worked in the same professions in the GW as in their pre-war civilian work but in the war zone, nurses were often assigned to different and unfamiliar roles. Only combat medical technicians (akin to civilian ambulance paramedics) worked in non-health civilian roles prior to the GW

Of the 95 HPVs, 27 (28%) had previous warfare experience and of these, 17 (18%) were ex Regular Reservists and 10 (10%) were in the TA. The remaining 68 (72%) had no experience of warfare. The time spent in the Gulf (in weeks) for most HPVs was between 8 and 12 weeks. When the HPVs’ length of time in the Gulf was compared with their deployment military categories using a Mann-Whitney U test. Reservists were found to have spent less time in deployment (mean rank=37.16) than those in the VS (mean rank = 58.61): a significant difference (U=618.500, Z= -2.414, p<0.01).

Eighty-four HPVs recorded their length of military service in a range of 1-36 years (mean=9.02, SD=7.52) with a median of 6.0. Of the 11 who failed to respond to this question, 6 were VS TA volunteers who could have regarded the question as seeking sensitive information and the remaining 5 were civilian Welfare Officers, who may have considered the wording of this question as being specific only to those in the military.

Table 1: The HPVs’ personal, professional and military characteristics.

*3 nurses were not in employment when called-up.

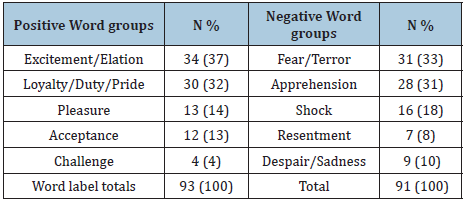

The HPV's initial reactions to call-up or acceptance as a volunteer

Ninety-three HPVs (2 missing) provided written comments describing their reactions towards being called-up (if a Reservist) or accepted as a volunteer (as a Reservist or a member of a part-time military service). Content analysis first identified 10 groups of word labels that either replicated or represented the HPVs’ original meaning within the comments prior to assigning them to either a positive or a negative reactions group. As shown in Table 1, of a total of 93 positive word labels, the most frequently occurring were ‘excitement/elation’ (34) and the altruistic qualities of loyalty /duty/ pride (30). Conversely, of the 91 negative word labels identified, fear/terror (31) and apprehension (28) were those most frequently subscribed to by the HPVs. There was little difference between the respective totals for these two word-label groups. Preliminary cross tabulations of these data categorised with 'present’ and ‘not present’ values for excitement/elation; fear/ terror; loyalty/duty/pride; shock and acceptance respectively showed that Reservists called up expressed higher percentage frequencies for fear/ terror; apprehension; shock and acceptance than volunteers (VS and Reserve) and conversely volunteers had higher percentage frequencies for excitement /elation; loyalty/ duty/ pride than those called up.

Further analysis of the comments in their entirety showed a more complex picture of feelings with word labels displaying opposite meanings within the same comment. Thus, the data were re-categorised into ‘positive reactions’ (30:33%); ‘mixed reactions’ (35:38%) (both positive and negative word labels occurring within the same comment) and ‘negative reactions’ (27:29%). The comments were scrutinised to identify preliminary themes and their related sub themes. Representative comments have been selected to illustrate these in comment boxes below.

Theme 1a. Positive anticipatory reactions to call-up and request for volunteers (N=30)

The first theme was for positive anticipatory reactions containing three sub-themes as shown in Comment Box 1a. The first was expressed as elation and excitement, received exclusively from volunteers who seemed to regard mobilisation as akin to going on a highly desirable adventure. In the second sub-theme, two comments suggest that some HPVs perceived their mobilisation as a positive opportunistic escape from problematic relationships at home. In the third sub-theme, the expression of altruistic military cultural values of selflessness, loyalty, duty and pride were made by some HPVs thereby adhering to the long-held expectations of the military and that of British society in time of war and peace.

Theme 1b. Mixed reactions to call-up and request for volunteers (N=35)

TA volunteers tended to combine their high commitment to positive anticipatory reactions with negative morbid thoughts of death as given in the first two comments. Only two of the 92 comments (both mixed reactions) made reference to the burden of separation that either they had imposed upon their families if volunteers or had been imposed by the State if they had been called-up (Comment Box 1b).

Theme 1c. Negative reactions to call-up and request for volunteers (N=27)

The remaining 27 comments were negatively framed. Nine comments, received only from Reservists called up, expressed discontent, registered as shock and devastation at being call up. There was also resentment towards Regulars who were not sent to the Gulf, thus necessitating the call up of Reservists. Others commented upon their clinical competency in terms of awareness that they were embarking on a major life event that they were professionally ill prepared for. The remaining 5 comments received exclusively from the 5 welfare officers, raised their concerns about their lack of military training, in particular for unconventional weaponry.

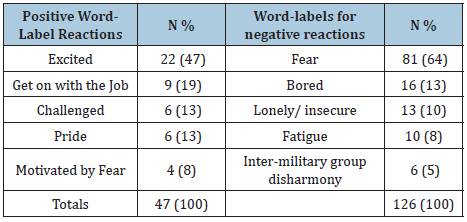

Reactions to the first weeks of deployment

Ninety HPVs provided comments describing their reactions to the first weeks of deployment in Saudi Arabia and 5 did not respond. Content word analysis created a total of 173 word- labels, as shown in Table 2, and of these, 47 were grouped as ‘positive’ word-labels and 126 were grouped as ‘negative’ word-labels’. Of the positive word-labels (47=100%), the following sub-themes emerged. Excited occurred with the highest frequency (22: 47%) and fear (perceived in this case as a positive protective mechanism) occurred the least frequently (4: 8%). Unlike before departure (see Table 1), the altruism reflected in duty and loyalty were far less in evidence in the first weeks of deployment, but pride continued to be included in a small number of comments. Of the negative word-labels (126=100%), fear (as an uncontrollable physiological response to a real-life threat) occurred the most frequently (81:64%). Finally, although mentioned with a low frequency, inter-military group disharmony (N=6) between Regulars, Reservists and TA personnel was introduced for the first time in the HPVs’ experiences of the first weeks in deployment (Comment Box 1c).

Table 2: HPVs’ (N=93) positive and negative reactions to mobilization.

Further thematic content analysis categorised 16 (17%) comments as a ‘positive reactions’ theme; 21 (22%), as shown in Comment Box 2a. Comments reflecting both positive and negative reactions were categorized as a ‘mixed reactions’ are shown in Comment Box 2b and the remaining 58 (61%) were categorized as a ‘negative reactions’ theme , shown in Comment Box 2c. Within each theme sub-themes were identified.

Theme 2a - Positive reactions towards deployment

As shown in Comment Box 2a, most of the positive comments were linked to the ongoing sub-theme of excitement or inspired by the shared purpose of getting on with the job they had been sent to the Gulf to do in terms of preparations for casualty care during the impending war.

Theme 2b - Mixed reactions to initial weeks of deployment

As shown in Comment Box 2b, the HPVs expressed the sub-theme of excitement combined with fear, not of the anticipatory kind given prior to departure but from exposure to the reality of warfare (SCUD missiles) and with the cognisance that they were in a situation of threat over which they could exercise little personal control. A few comments received only from Reservists called up expressed the sub-theme of frustration and uncertainty at their work situation in which no role had been planned for them. This appeared to have been compounded by a lack of information. In contrast, a mixed comment from a VS nurse (who was likely to have spent a longer time in the Gulf than Reservists), being 'busy' presumably meant there was a role for her. In addition, as her experience of fear was described as 'shared' which could imply that she had established some supportive relationships. A few comments received only from Reservists called-up expressed the theme of discontent, registered in terms of frustration and uncertainty at their situation in which, unlike the circumstances of the above comment from a deployed TA VS person, no role had reportedly been planned. This appeared to have been compounded by lack of information and at a time when coping with adaptation to a new and dangerous situation:

Theme 2c. Negative comments towards initial weeks of deployment

Negative comments formed three sub-themes as shown in Comment Box 2c. In the first, the comment contained negative reactions related to a paralysing fear with the realisation of the danger that they were in and in the second, a morbid uncertainty concerning a lack of training undermined confidence. Some comments mention the comfort derived from knowing that everyone else was also afraid, although efforts seem to have been made to put a brave face on it. In the second theme, the comments contained the ongoing resentment expressed by some Reservists that they had been called up when Regulars they knew at home were not. In this related comment such feelings were fuelled by the expression of anticipatory fear arising from doubt related (in this case) to his or her personal ability to cope with the expected challenging casualty workload. One HPV Welfare Officer's comment raised fear arising from her lack of military training, and represents similar comments made by all Welfare Officers. She also raised her sense of isolation from being a latecomer trying unsuccessfully to join established groups.

Quantitative analysis of data for early reactions to deployment

The qualitative data were transformed into a new dichotomous variable ‘early reactions to deployment’ with the categories of ‘negative reactions’ (N=56: 61%) and ‘other’ (positive and mixed reactions) (N=37: 39%). When this new variable, acting as a dependent variable (DV) was entered with sample characteristics as independent variables (IVs) into a logistic regression model, military category was found to be the best predictor variable with Reservists having a significantly greater likelihood of being negative about the first weeks in deployment than those in the VS TA (B=1.154,df=1, r=0.009; Exp(B)= 3.170., p<0.01)

The HPVs identification of their most difficult aspect of deployment

The HPVs were asked which (if any) aspects of deployment they had found the most difficult to cope with. As shown in Table 3, 83 (87%) HPVs provided comments from which 111 word-labels were generated. The remaining 12 said there was not anything that could not be coped with. As shown in Comment Box 3a, 6 sub-theme groups were created from the word labels. Of particular interest was the contrast between the earlier HPVs’ reactions to the first weeks in the Gulf (Comment Box 2a) where fear was frequently subscribed to, but it was not identified as an aspect that was difficult to cope with during deployment as a whole. This was possibly because after the SCUD attacks had ceased and ground preparations had been completed, this gave way to a period of boredom waiting for the land offensive to commence. The sub-theme ‘inter-military group disharmony’ (encompassing inter-military, inter-personal and inter-professional difficulties), although infrequently raised earlier for the first weeks of deployment, was reported as the most difficult aspect coped with during deployment overall. All of the remaining sub-theme groups: ‘uncertainty’, ‘boredom/inactivity’, ‘separation from home’ and ‘deprivation from living conditions’ had low frequencies of between 12% and 15% of the total number of word labels for each group.

Table 3: Word-labels for HPVs’ initial reactions towards deployment (N=173).

*percentages calculated from the total number of word labels, N=111.

Sub-theme 3a - Inter-group disharmony

Two forms of disharmony were identified within the theme of inter-group disharmony: i] disharmony due to the attitudes of other military personnel, and ii] disharmony due to rank differences and perceived management deficiencies. The HPVs’ comments of relevance to these sub themes are given in Comment Box 3a. The first sub-theme describes stereotypical behaviour, whereas in the second sub-theme, inter military group disharmony was associated with personnel of senior rank and their perceived lack of leadership. The effect from either or both was to weaken teamwork and group cohesion.

Sub-theme 3b - Uncertainty/ lack of confidence and boredom

The theme of uncertainty was related mainly to the unknown length of time for deployment, the expectation of mass casualties (that in the event did not happen), and the individual’s ability to cope professionally (and often in circumstances of limited material resources) as captured in one comment. Comments related to boredom provided little detail, other than reflecting the waiting around for things to do but as illustrated in one comment, this had its own set of adverse effects in terms of irritation and fatigue (Comment Box 3b).

Sub-theme 3c - Relationship problems and concerns for those at home

Unlike the reactions to mobilisation where the HPVs appeared almost wholly focussed upon themselves rather than the families they were about to leave behind, concerns for those at home during deployment included a sense of helplessness and guilt in not being able to alleviate the anxieties that their participation was causing those at home. For a few HPVs, perceived changes in relationships with those at home was a source of additional stress (Comment Box 3c).

Sub-theme 3d - Deprivation from living conditions

The comments in this theme further illustrate some HPVs’ perceived loss of personal control when in the role of ‘the soldier’ during GW deployment. In particular, as in the first comment, females in support locations found confinement with others randomly chosen as companions, a challenging situation. As in the second comment, the imposed restrictions upon the freedom of females to meet the Muslim cultural values of Saudi Arabia as the host nation was a further constraint. The two last comments relate to those based in desert-based field hospitals where basic and unsavoury conditions of a tented life in the desert presented daily challenges often described with a sense of humour (Comment Box 3d).

Sub Theme 3e. Fear

In this final sub-theme, all of the comments continued to be associated with the anticipatory threat of attack (12%) (particularly that of NBC agents) but with a frequency of occurrence markedly diminished from that given for the reactions to prospect of mobilisation (31%) and the first weeks in the Gulf (64%):

‘The continual threat and fear of attack/NBC hanging over all of us.’

(Female Reservist called-up, junior officer nurse.

Quantitative data analysis for aspect of deployment the most difficult to cope (inter-military group disharmony)

The data for the 30 (33%) HPVs with inter-military group disharmony were transformed into a new dichotomous variable of ‘deployment social relationships’ with the values of ‘1. Difficulty’ and ‘2. No difficulty’. This variable was entered as a DV with sample characteristics as IVs into the logistic regression model and length of military service (longer) was identified as the best predictor of difficulty with those with a longer time in military service having a significantly greater likelihood of being subjected to inter-military group disharmony identified as their most difficult thing that they coped with during deployment (B=0.068;df-2; r=0.07 Exp(B)=1.070; p<0.05)

Discussion

The HPVs' use of words such as 'excitement' and 'duty 'have frequently been associated with a commitment to warfare [30]. Younger people have been described as perceiving situations of danger as producing excitement likened to participation in a dangerous sport or undertaking a testing adventure. However, as reflected by the HPVs’ age range, the desire to ‘risk all’ in going to war was not confined to youth but also included those in mid-life. This has been recognised as a time when the participant has an increased focus upon actions that benefit society or other external purposes and with the tendency to abandon responsibilities in the pursuit of adventure [31].

The HPVs with negative reactions to pre-deployment mobilisation, tended to express these as fear. This was not associated with the spirit of adventure (evident before departure to the Gulf) but to a negative anticipatory expectation of personal harm or death from attack and in particular, from contact with chemical or biological agents. In the main, those registering negative reactions towards mobilisation were called-up Reservist nurses, who also expressed self-doubt as to the adequacy of their civilian skills to meet the needs of the anticipated high casualty workload. that they anticipated lay ahead. The mixture of fear with anxiety was also marked in the comments of the five Welfare Officers, who reported that prior to departure they had not received military training to protect themselves against biological or chemical attack. In contrast, for some TA VS participants, early participation in the GW was anticipated and appraised as affording the opportunity to test their part-time learning of military skills and they were (in the main), eager to depart for the Gulf as volunteers.

The anticipatory fear of pre deployment, was largely masked by the HPVs' reliance upon altruistic qualities such as pride, sense of duty and commitment to a cause. This changed dramatically into real fear with the experience of being under attack in the early part of the war that consequentially diminished the use of altruistic sentiments expressed at mobilisation. Some HPVs recorded that they tried to keep 'a stiff upper lip’ in times of adversity, thereby adhering to the ideal of the 'macho warrior-type' values of uncomplaining courage and resilience as a protection from being perceived as weak by their peers [20-23]. For Reservists called-up there were other concurrent stressors, for many arrived in the Gulf having perceived their training in the UK to be poor or bad [32].

In particular, less than 10% of the HPVs were recipients of stress management training ((and these were exclusively in the TA) [32]. As the latecomers to deployment Reservists had less time to adapt to the stressors of the environment such as: the extremes of the climate [33] and the flies and basic sanitisation [34]. Above all, when joining established military groups of Regulars and TA, they felt that they were treated as 'outsiders' [35]. Furthermore, some Reservists called-up recalled their frustration and anger with the military in finding on arrival in the Gulf, that their expected roles were not allocated to them. Role clarity is described as being crucial to the individual and team’s sense of locus of control [36]. These factors, plus the perceived disregard of some Regulars for the higher rank particularly of TA personnel, was described as damaging to unit cohesion and morale as well as undermining clinical decision-making and teamwork. The HPVs with a longer service in the military were those most likely to report inter-military group disharmony. It is possible that these HPVs (exclusively in the TA) adhered to the illusion of the past as being better than the present. This occurs when people adopt a judgmental bias causing them to mistake change in themselves as change in the external world [37].

Disharmony between different military groups including both TA and Reservists was the most difficult aspect coped with by the HPVs, yet there is no evidence to suggest that this was addressed by senior command. To the contrary some HPVs made the general criticism of their lack of expected care and leadership. Experiencing social isolation from the perceived rejection by other members of a team is reportedly one of the most psychologically damaging occurrences for military persons under pressure from wartime stressors and threats, for it renders them unable to share their concerns and fears [21].

Finally, despite the passage of time, much can be learned from the Gulf War in terms of management, particularly as the British military is presently engaged in changing the manpower balance toward a higher number of part-time soldiers and a reduction in its Regular forces [38-46].

Limitations

Due to the constraints of finance, distance and security, no access was available to either a representative military sample or suitably selected controls. These limit generalization of the findings to their wider HPV populations [47-52]. However, the mixed method approach is believed to have maximized understanding of these particular HPVs’ responses and increased the trustworthiness of the findings for this particular cohort [52-58].

Conclusion

Importantly, the findings show that over time for the HPVs during deployment the nature of stressors changed [58-64]. From the anticipatory fear of pre deployment to the real fear of death or injury on arrival in the Gulf both were superseded by a gradual increase in the stressor of inter-personal and organizational disharmony between military group. Undoubtedly their responses towards the circumstances of this modern war with its unconventional weaponry threat are valuable to a future in which a similar threat could arise [65-70]. However, although preserving the macho image may help Regular troops strengthen their resolve and aid military group cohesion, it may be less meaningful to the Reservist called-up whose civilian life has been disrupted for a return to military life that they thought they had left behind. Military entrants who are essentially civilians will require much more nurture and understanding if they are to be effective [71-76].

References

- Stanwood F, Allen P, Peacock L (1991) Gulf War: A Day by day chronology (BBC World Service), Heinemann Ltd., London, UK.

- Knudson GB (1991) Operation desert shield: Medical aspects of weapons of mass destruction. Military Medicine 156(6): 267-271.

- de la Billiere P (1992) Storm command: A personal account of the Gulf War. Harper Collins Publishers, UK.

- Nye JS, Smith RK (1992) After the Storm. Lessons from the Gulf War. The Aspen Institute-Madison Books, UK.

- Plutchik R, Kellerman H (1980) Emotion: theory, research, and experience. The American Journal of Psychology 94(2): 370-372.

- Ortony A, Turne TJ (1990) What's basic about basic emotions? Psychological Review 97(3): 315-331.

- Baumgartner H, Pieters R, Bagozzie RP (2008) Future-oriented emotions: Conceptualization and behavioral effect. European Journal of Social Psychology 38(4): 685-696.

- Jarymowicz M, Ban TD (2006) The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. European Journal of Social Psychology 36(10): 367-392.

- Stemmler G, Heldmann M, Scherer T (2001) Constraints for emotional specificity in fear and anger: the context counts. Psychophysiology 8(2): 275-291.

- Cadigan F (1982) Battleshock - the chemical dimension. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 128(2): 89-92.

- Brooks FP, Ebner DG, Xenakis FR, Balson PM (1983) Psychological reactions during chemical warfare training. Military Medicine 148(3): 232-235.

- Xenakis SN, Brooks FR, Balson PM (1985) A triage and emergency treatment model for combat medics on the chemical battlefield. Military Medicine 150(8): 411-415.

- Cooper C (1991) Saddam Hussein - my part in his downfall. Queen Elizabeth College of Nursing and Health Sciences Magazine 3: 2-3.

- Dickinson JG (1991) My gulf war. Journal of the royal college of physicians of London 25(4): 347-350.

- O’Brien LS, Payne RG (1993) Prevention and management of panic in personnel facing a chemical threat - lessons from the Gulf War. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 139(2): 41-45.

- Kirkland FR, Halverson RR, Bliese PD (1996) Stress and psychological readiness in post-cold war operations. Parameters, pp.79-91.

- Nash WP (2007) The stressors of war. Combat stress injury: Theory, research and management. Taylor and Francis Group, Routledge, New York, USA, pp.11-31.

- Hall LK (2011) The importance of understanding military culture. Social Work in Health Care 50(1): 4-18.

- Greene T, Buckman J, Dandeker D, Greenberg N (2010) The impact of culture clash on deployed troops. Military Medicine 175(12): 958-963.

- Mead M (1940) Warfare is only an invention - Not a biological necessity. In: Bramson L, Goethals GW (Eds.), War. Studies from Psychology, Sociology and Anthropology (4th edn), USA, pp. 269-274.

- McManners H (1993) The scars of war. Harper Collins Publishers, USA.

- Kirke CSM (2005) Grappling with the stereotype: British Army culture and perceptions, an anthropology from within. Conference paper. Recontextualizing and reconceptualizing delineations and infusions of militarization in organizational theory and lives. CMS, UK.

- Shephard B (2002) A war of nerves. Soldiers and psychiatrists 1914-1994. Pimlico, UK.

- Hogg M, Reid SA (2000) Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Communication Theory 16(1): 7-30.

- Rosen LN, Knudson KH, Fancher P (2003) Cohesion and the culture of hypermasclinity in u.s. army units. Armed Forces and Society 29(3): 325-335

- Creswell W (2003) Research design: qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications, USA.

- Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Sage, UK, pp. 272-273.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych 3(2): 77-101.

- Merrill J, Williams A (1995) Benefice, respect for autonomy and justice: principles in practice. Nurse Res. 3(1): 24-34.

- Lorenz K (1996) On aggression. (2nd edn), Routledge, UK.

- Erikson E (2001) The Erikson reader. In: Robert C (Ed.), WW Norton and Co, USA, pp. 391-392.

- Wild D (2018) UK gulf war health professional veterans’ perceptions of and recommendations for pre-deployment training: the past informing an uncertain future? Research & Reviews, Health Care Open Access Journal 2(2): 143-149.

- Oldfield EC, Wallace MR, Hyams KC, Yousef AA, Lewis DE, et al. (1991) Endemic diseases of the middle east. Rev Infect Dis. 13(Suppl 3): 199-217.

- Young RC, Rachal RE, Huguley JW (1992) Environmental health concerns of the persian gulf war. J Natl Med Assoc 84(5): 417-424.

- Janis IL (1982) Groupthink (2nd edn), Houghton Mifflin, USA, pp. 9-12.

- Manton J, Wilson C, Braithwaite H (2000) Human factors in field training for battle: realistically producing chaos. In: Evans M, Ryan A (Eds.) The human face of warfare. Allen and Unwin, Australia, pp. 177-197.

- Eibach RP, Libby LK (2009) Ideology of the good old days: exaggerated perceptions of moral decline and conservative politics. In: John TJ, Aaron CK, et al. (Eds.) Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification. Oxford Scholarship, UK.

- Ministry of Defence (2013) Reserves in the future forces 2020: valuable and valued. Ministry of Defense, The Stationery Office Ltd, UK.

- Stanwood F, Allen P, Peacock L (1991) Gulf war. a day by day chronology. BBC World Service, UK.

- Knudson GB (1991) Operation desert shield: medical aspects of weapons of mass destruction. Mil Med 156(6): 267-271.

- Billiere P (1992) Storm command: a personal account of the gulf war. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- Nye JS, Smith RK (1992) After the storm lessons from the gulf war. London.

- Plutchik R, Kellerman H (1980) Emotion: theory, research, and experience. Theories of Emotion, New York, USA, pp. 3-33.

- Ortony A, Turner TJ (1990) What's basic about basic emotions? Psychological Review 97(3): 315-331.

- Baumgartner H, Pieters R, Bagozzie RP (2008) Future oriented emotions: conceptualization and behavioral effect. European Journal of Social Psychology 38(4): 685-696.

- Jarymowicz M, Ban TD (2006) The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. European Journal of Social Psychology 36(10): 367-392.

- Stemmler G, Heldmann M, Scherer T (2001) Constraints for emotional specificity in fear and anger: the context counts. Psychophysiology 38(2): 275-291.

- Cadigan F (1982) Battleshock the chemical dimension. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 128(2): 89-92.

- Balson PM (1983) Psychological reactions during chemical warfare training. Military Medicine 148(3): 232-235.

- Xenakis SN, Brooks FR, Balson PM (1985) A triage and emergency treatment model for combat medics on the chemical battlefield. Mil Med 150(8): 411-415.

- Cooper C (1991) Saddam hussein my part in his downfall. Queen Elizabeth College of Nursing and Health Sciences Magazine. 3: 2-3

- Dickinson JG (1991) My gulf war. J R Coll Physicians Lond 25(4): 347-350.

- Obrien LS, Payne RG (1993) Prevention and management of panic in personnel facing a chemical threat lessons from the gulf war. J R Army Med Corps 139(2): 41-45.

- Kirkland FR, Halverson RR, Bliese PD (1996) Stress and psychological readiness in post-cold war operations. Parameters 26(2): 79-91.

- Nash WP (2007) The stressors of war. In: Figley CR, Nash WP (Eds.), Taylor and Francis Group, New York, USA, pp. 11-31.

- Hall LK (2011) The importance of understanding military culture. Soc Work Health Care 50(1): 4-18.

- Greene T, Buckman J, Dandeker D, Greenberg N (2010) The impact of culture clash on deployed troops. Military Medicine 175(12): 958-963.

- Mead M (1940) Warfare is only an invention not a biological necessity. In: Bramson L, Goethals GW (Eds.), War Studies from Psychology, Sociology and Anthropology. (4th edn), Basic Books Incorporated, New York, USA, pp. 269-274.

- McManners H (1993) The scars of war. Harper Collins Publishers, London.

- Kirke CSM (2005) Grappling with the stereotype: british army culture and perceptions, an anthropology from within. Conference paper. Recontextualising and reconceptualising delineations and infusions of militarization in organizational theory and lives. CMS, Cambridge, USA.

- Shephard B (2002) A war of nerves. Soldiers and psychiatrists 1914-1994. Pimlico, p. 498.

- Hogg M, Reid SA (2000) Social identity, self categorisation and the communication of group norms. Communication Theory 16: 7-30.

- Rosen LN, Knudson KH, Fancher P (2003) Cohesion and the culture of hypermasculinity in U.S. Army Units. Armed Forces and Society 29(3): 325-351.

- Creswell W (2003) Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. In: Creswell JW, Creswell JD (Eds.), (5th edn), Sage Publications, USA.

- Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publication, Newbury Park and London, USA, pp. 272-273.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psych 3(2): 77-101.

- Merrill J, Williams A (1995) Benefice, respect for autonomy and justice: principles in practice. Nurse Res. 3(1): 24-34.

- Lorenz K (1996) On aggression. (2nd edn), Routledge, London and New York, USA.

- Erikson E (2001) The Erikson reader. In: Robert Coles (Ed.), WW Norton and Co., New York, USA. pp. 391-392

- Wild D (2018) UK gulf war health professional veterans’ perceptions of and recommendations for pre-deployment training: the past informing an uncertain future? Research & Reviews on Health Care Open Access Journal 2(2): 143-149.

- Oldfield EC, Wallace MR, Hyams KC, Yousef AA, Lewis DE, et al. (1991) Endemic diseases of the Middle East. Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 13(Supplement 3): 199-217.

- Young RC, Rachal RE, Huguley JW (1992) Environmental health concerns of the Persian Gulf War. J Natl Med Assoc 84(5): 417-424.

- Janis IL (1982) Groupthink. In: (2nd edn), Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, pp. 9-12.

- Manton J, Wilson C, Braithwaite (2000) Human factors in field training for battle: realistically producing chaos. In: Evans M, Ryan A (Eds.), The human face of warfare. St Leonards, Allen and Unwin, New South Wales, Australia, pp. 177-197.

- Eibach RP, Libby LK (2009) Ideology of the good old days: exaggerated perceptions of moral decline and conservative politics. In: Jost JT, Kay AC, Thorisdottir H (Eds.), Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification. Oxford Scholarship, UK.

- Ministry of Defence (2013) Reserves in the Future Forces 2020: Valuable and valued. London: Ministry of Defence. The Stationery Office Ltd. London, UK.

© 2020 Elham Hedayati. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)