- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Degree of Disaster Preparedness of Families

Rufina C Abul, Abdel Carlos*, Cervancia, Vanessa Ann Obille, Eunice Laguna, Leah Lyne Peralta and Kassandra Kate

Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author: Abdel Carlos, 3280 Al Hadf Street, Mishrifah District, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Submission: January 30, 2019;Published: January 23, 2020

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

Background: The family has a crucial role during disaster. It is a principal conduit for disaster behaviors and critical for its individual members’ survival. Clason concluded that families have proved themselves not only essential reproductive units, but also as core social units enhancing its members’ survival. Global policies on disaster risk reduction have highlighted individual and community responsibilities and roles in reducing risk and promoting coping capacity. A predominant gap in the literature is the need for evidence-informed strategies to overcome the identified challenges to family preparedness.

Purpose: This study determined the degree of disaster preparedness of families on the dimensions of resources, disaster plan, knowledge on earthquake, typhoon and flood response, disaster skills, the attitudes of families towards disaster preparedness and the association of variables.

Methods: The study utilized the quantitative descriptive-correlational design. The respondents consisted of 399 household heads in the city of Baguio, chosen through systematic, cluster sampling process. Data were gathered utilizing a group made questionnaire, and were treated using counts, means, ANOVA and Pearson correlation coefficient.

Result: The findings revealed that from a scale of excellent, good, fair and poor, the degree of disaster preparedness of families is only “good” while families have “fairly positive” attitude towards disaster preparedness. There is a weak correlation between attitude and degree of preparedness.

Conclusion:

Families still cannot adequately respond to disaster, with several areas needed to be enhanced.

Majority of the families do not find it necessary to prepare disaster supplies ahead of time. Several still don’t see the need to do so.

Families still need to come together to agree on what to do in case of disaster.

Not all are ready to respond to earthquake.

Families are knowledgeable enough on how to respond to typhoon and landslide.

There is a need to enhance training on disaster response and basic life skills.

Families have some negative perceptions related to disaster preparedness.

The selected variables do not significantly influence degree of preparedness and attitudes toward disaster preparedness.

Attitudes toward disaster do not influence much the degree of preparedness of families on disaster. In terms of disaster, they just have to do what can be done regardless of whether they have negative perception of things. Negative beliefs can be set aside in disaster situations.

Keywords: Disaster preparedness; Determinants of disaster preparedness; Disaster preparedness among families

Introduction

The Philippines ranked third on a list of countries most exposed to natural disasters for the past 45 years. The United Nations economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [1] reported that deadly and costly earthquakes, and the effects of global climate change that includes stronger storms, floods, droughts and sea level rise are what usually plague the Philippines.

Baguio is not spared from these effects of climate change. Owing to its geographical location, the place and its people are vulnerable to typhoons, earthquakes, and landslides. The effects of the degradation of the forests such that trees are being cut down; mountains are flattened and being taken place by buildings, makes the place more prone to landslides that results to destruction of lives, properties, and livestock, power interruption and road closure. During these events, families need to look into the availability of resources that may become scarce or compromised such as food, water and materials that will be utilized to counteract unforeseeable events.

The United Nations World Conference was organized to come up with the Sendai framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. It aims to build the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. Its goal is to focus on preventing new risk, reducing existing risk and strengthening resilience. It has four Priorities for action which include the following:

- Understanding disaster risk,

- Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk,

- Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience, and

- Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction [2].

The Framework envisions a country of “safer, adaptive and disaster resilient Filipino communities toward sustainable development.” This present study will focus on Sendai framework priority 4, Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response; and National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plan (NDRRMP) area 2-Disaster preparedness. Despite this vision and program implemented by the National Government it cannot be denied that destruction of both lives and properties still occur during calamities. Some may be inevitable, but guidelines as to measures on how to counteract unwanted effects of calamities are in place [3].

Several studies about disaster preparedness have already been conducted in the international arena. In the Philippines, the Health Research and Development Information Network, the national health research repository of the Philippines shows only 16 articles related to disaster. Most of the studies focus on manmade disaster. Arcillana studied preparedness to natural disasters in Central Luzon disaster prone barangays but this was conducted in 1979-that was 3½ decades ago. It is high time that researches should be focused on here-and-now since the complexity of preparedness, involving personal and contextual factors such as health status, self-efficacy, community support, and the nature of the emergency need to be considered.

The family has long been considered a fundamental unit in the study of disaster behavior. In addition, Institute of Medicine in 2013 forum promotes disaster preparedness specifically for children and their families. Redlener warned that it takes a long time to recover from a disaster. People take far longer to recover than the infrastructure does and protecting kids from the psychological trauma of big events requires an adult to buffer them. The nation needs to learn to cope with the "resilience erosion". In addition, people require sufficient knowledge, motivation and resources to engage in preparedness activities. Social networks have been identified as one such resource which contributes to resilience. A predominant gap in the literature is the need for evidence-informed strategies to overcome the identified challenges to family preparedness.

Considering the facts and arguments above, the study aims to endeavor into finding answers to the following research questions:

- What is the degree of preparedness of families on disaster, along the following dimensions?

- Availability of Resources

- Presence of Disaster Plan

- Knowledge on Earthquake

- Knowledge on Landslide

- Knowledge on Typhoon and Floods

- Competency in performing disaster related skills

- What are the attitudes of families towards disaster preparedness?

- Is there a significant difference in the degree of preparedness, and attitudes of families on disaster when group according to:

- Household ownership

- Household construction

- Family structure

- Economic status

- Cultural background

- Is there a significant relationship between the attitudes towards disaster preparedness and the degree of preparedness?

The Health Belief Model serves as the framework of this study. This model states that an action (in this study, disaster preparedness) is influence by simultaneous occurrence of 3 classes of factors which are (a) existence of a sufficient motivation or health concern, (b) belief that one is susceptible to a serious health problem and to its sequence known as perceived threat, and, (c) belief that the action will lead to a reduction of the threat. In this study, the health concern is the need to prepare for any calamity that may bring disaster to the family since these calamities may lead to loss of life, properties and/or source of income (threat). Taking action prior to the impact of any calamity will greatly reduce the threat.

The HBM further explains that the action is also influenced by demographic factors of the individual which can pose as barriers to action and may influence the perception of how beneficial the action is. This perceived benefit, the barriers and the three (3) factors above will all converge to influence the decision of the individual to take action.

In this study, the demographic factors include household ownership, house construction types, economic status, family structure and the cultural background. The researchers have determined the influence of these variables to the degree of preparedness and the attitudes about taking the action related to calamities and disaster. This study is considered significant since some items in the questionnaire have provided awareness to the community regarding the need for families to be prepared anytime for unanticipated events or calamities. Findings will also serve as a basis in assessing the vulnerability of the families to disaster. For families and communities, findings can serve as basis to educate citizens on the importance of disaster preparedness in the primary care setting. Similarly, it can serve as ground to develop strategies in enhancing the families’ knowledge and skills in disaster preparedness. Nursing education can use findings as a basis for strengthening competency-based emergency and disaster preparedness curriculum, while groups or concerned government and non-government institutions, can use the results for developing programs, activities, policies, guidelines, and modules on disaster preparedness.

Methods

The study utilized the quantitative descriptive-correlational design. The study was conducted in Baguio City. Respondents included the primary decision maker of the family. Data gathering took place from January 6 to February 15, 2016. It included the traditional family (nuclear or extended) composed of child or children with at least one married couple and their relatives; and single-family units (group of adults who are non-married/noncouple living together). It excluded respondents aged below 18 years old or 65 years old and older and those who do not contribute to the earning of the family or are unable to make decisions for the family.

The sample size was 398-399. The total sample was divided equally to the 18 districts of the city using proportionate sampling (to determine number of samples per district) then simple random was used to determine specific barangays in each district that was included in the study. After determining the specific barangays, systematic random is used to determine specific households that are considered as actual respondents for the study.

Systematic sampling was used to determine the households that are included in the study by choosing every 5th household from the barangay hall of the chosen barangay. Below is Table 1 which presents the demographic profile of the respondents for this study. The table shows that majority (59%; 236/399) of the households are owned, while 68% (266/399) of the households are made up of mixed wood and concrete, 61% (f=241) of the total population of the families are nuclear in structure. The monthly income of 43% (f=167) of the respondents ranges from 6,001 to 15,000, and most of the respondents are Ilocanos which comprise 39% of the respondents (154/396), followed by 23% Cordillerans (90/396), and 19% (74/396) Tagalogs. The tool utilized to gather data for this study is a group-made questionnaire. The contents were based on the guidelines for disaster preparedness taken from various literatures obtained from different search engines.

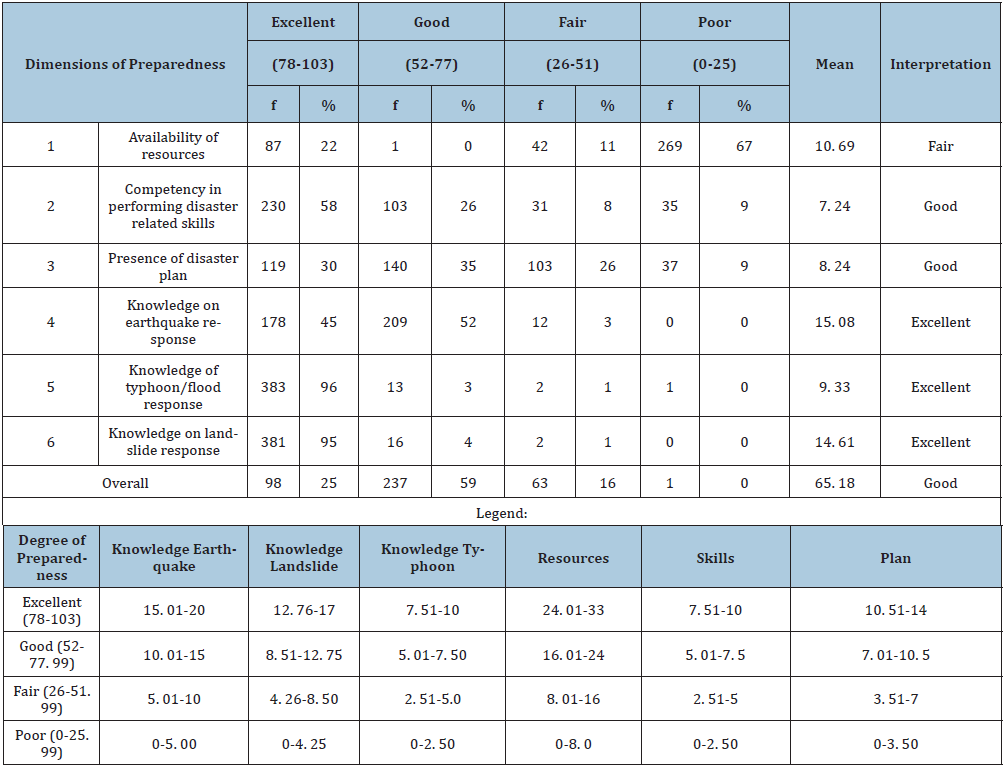

Table 1: Degree of preparedness of families on disaster ((N=399).

The questionnaire consists of three components; the first part elicits the demographic items regarding family variables such as household ownership, family structure, economic status and cultural background is correlated in this study with the degree of preparedness of the family. The second part consists of different questions that assessed the degree of preparedness among families. Preparedness is measured along the dimensions of availability of resources needed during a calamity, presence of family disaster plan, knowledge on how to respond during an earthquake, typhoon and landslide, and competency in performing skills in response to a disaster/calamity. The degree of preparedness was measured using a “yes”/”no” response. The third part assessed the attitude of respondents towards disaster preparedness. A four-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agrees to strongly disagree were given as choices. The validity of the questionnaire was established by subjecting it to the evaluation of Datud J, Pachao R, and Canilao CA. The validity index of the tool was computed as 0.92 hence, considered valid [4].

The researchers’ sought approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the Institution with protocol no. SLU - REC 2015 - 088, before actual data gathering. After approval was obtained, the following processes were undertaken:

- Gatekeepers of each chosen barangay were identified and their approval for the conduct of study in their barangay was sought.

- After the approval by the barangay officials, sites for actual data gathering was set, and respondents were determined.

- Data gathering commenced through consent taking where voluntarily participation in the study was observed by providing letter of consent to the respondents.

- The distribution of the questionnaires followed after participant consented to the study. The questionnaire was retrieved after an agreed upon time of completion with the respondents.

- During the retrieval of the questionnaire, completeness of the answers was checked. In the event that certain items were left unanswered, the researchers immediately gave the questionnaire back for the respondents to complete.

- Questionnaires were given codes and data were tallied using Excel program.

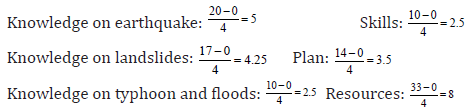

The degree of preparedness was determined by adding all “correct” response to the items of the different dimensions. Descriptive statistics was used to determine degree of preparedness for the different dimension. Scores to the items were tallied and preparedness was described using the four categories to classify the patient per variables. The sum of the correct responses was classified into four categories which are “excellent”, “good”, “fair” and “poor’. To get the arbitrary value for the:

The researchers used ANOVA to determine differences in degree of preparedness for the variable’s household ownership, household construction, family structure, economic status and cultural background.

The attitude of the families related to disaster was determined whether it is positive or negative based on the total score taken by summing up the corresponding points from the 13 items attitude questionnaire. Initially, scores for the items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 13 were reversed. The higher the score, the more positive is the attitude.

The attitude scores were interpreted as follows:

To determine the significant difference of attitude according to the study variables were determined using ANOVA. To determine the relationship between the attitudes towards disaster preparedness and the degree of preparedness, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used.

Result

Degree of preparedness of families on disaster along selected dimensions

In terms of resources, majority (67%) of the population of the study belongs to the “poor” (0-25) category of preparedness. Although the overall mean is “fair” (10.69), this figure is still not acceptable considering dangers/threats posed by calamities. In this study resources are defined as the availability of materials that include disaster kit that contains bottled water, ready to eat foods, first aid kit, clothing, medications and gadgets including cellphones and radio with extra battery, and contact numbers needed during emergency.

Although 26% (52 out of 200 respondents) claimed that they have the supplies ready during calamities, 19% (10 respondents) did not keep it in a ready to carry bag since they perceived that it is not needed. Others claim that they have not been affected by calamities in the past, thus, there is no need to prepare Financial reasons (18%=36 out of 200 respondents) also prevented families from having the disaster bag. It may not be possible for them to purchase materials for the kit as it is more important to ensure availability of needs for each day.

The contents of the disaster kit are equally important. Among those which are not usually given attention reveals that wrench (54 respondents), can opener (40 respondents), and whistle (40 respondents) has the highest proportion while for those which are given attention most are Alcohol (127 respondents) which is included in the content of the first aid kit, flashlight (127 respondents) and medications (123 respondents).

Another dimension of disaster preparedness is the presence of competency in performing disaster related skills; Majority 58% (230 families) belongs to the “excellent” category of preparedness. This may indicate that not all people are the same; they have their own understanding to a particular situation and at the same time initiative to respond to the possible threat that will be brought about by a calamity.

Similarly, the third dimension is the presence of disaster preparedness plan. Out of 399 respondent’s majority 35% belongs to the good category and has a mean of 8.24 which is also interpreted as “good”. It was found that 51% of the participants have a specific place where they can evacuate during a disaster while 49% do not have. This finding explains that the respondents consider the fact that their home may be unsafe to occupy so therefore agreeing as a family where to go when calamities will strike. Among the possible places identified by the respondents for evacuation include the barangay hall (34%; 29 respondents), the school (20%; 24 respondents), house (14%; 20 respondents), court (10%; 14 respondents), and open area (9%; 13 respondents). Despite the absence of mode of communication 39% have a family plan regarding the meeting place or where to come together when a calamity strikes while 61% do not have family plan. Respondents have identified barangay hall as the highest (24%; 69 respondents) as their meeting place, followed by open area (5%), house (5%), court (6%), and school (12%).

As to the compilation of important documents, 90 % have devised ways to keep their documents safe. Among the measures to protect and save the documents include keeping it in a safe and waterproof envelop or container. Others have scanned and copied their files in compact discs or flash drive. The remaining 10% did not find it important to keep their documents safely.

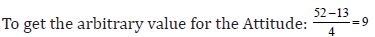

Table 2 shows that majority (90%) of the participants are knowledgeable about wound care. This may mean that respondents anticipate that during a disaster event, the risk of injury is high and will definitely urge the respondents to perform the necessary skills needed in case a member of the family gets injured. The second skill which is also given the highest attention is the “Knowledge about safety measures during earthquake” where 84% (337/399) of the total respondents claims they have knowledge on this area. The study also revealed that 79% (315/399 respondents) of participants knows how to make things at home safe during earthquake while 73 % (307/399 respondents) knows how to manage environmental dangers and make structure of house safer.

Table 2: Frequency of respondents possessing disaster related skills.

The study also revealed that 37% (148/399 respondents) of participants do not know about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation competency is defined as having the cognitive knowledge and psychomotor skills that are necessary for the effective performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in cardiac arrest situations.

Another skill that was given the lowest attention is how to purify water (121/399=30% not knowledgeable). The health of survivors of a natural or manmade disaster is exposed to high risk even if the actual disaster was of short duration. In most disasters and other emergencies, the main health problems are caused by poor hygiene due to insufficient water supply and the consumption of contaminated water.

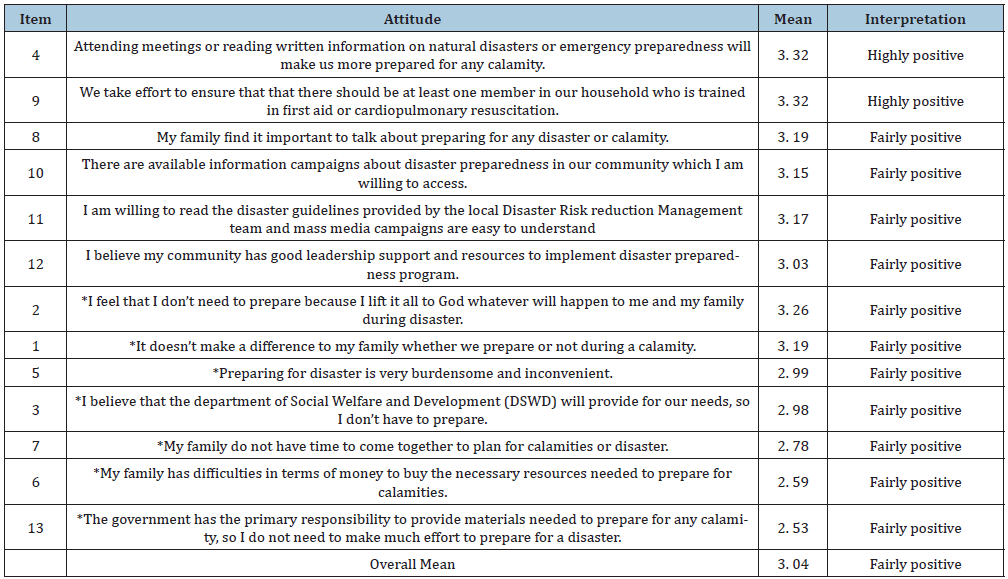

Attitudes of families toward disaster preparedness

Table 3: Degree of attitude of families towards disaster preparedness.

Table 3 consists of 13 statements pertaining to attitudes on disaster preparedness. Seven of which are negatively stated while six are positively stated. These attitude statements were rated in accordance to the perception of the respondents using a four-point Likert score which here include strongly agree (4), agree (3), disagree (2) and strongly disagree (1). The result obtained from the overall attitude of the respondents’ shows a total mean of 3.04 which is interpreted as a fairly positive attitude.

Obtaining a total mean of 2.99 (fairly positive), 48.12% of the population disagrees that “preparing for disaster is very burdensome and inconvenient”. Farely and Walkey suggest that risk perception increases preparedness behavior, but only if the risk has been personalized. The likelihood of an event occurring are unrelated to preparedness unless the individual truly believes the event will impact him or her directly. Financial concern is one factor that may influences preparedness. Among the respondents, 44.36% disagree that here are no difficulties in terms of money to buy the necessary resources needed to prepare for calamities.

Obtaining 51.38% of the respondents disagrees with item 7, that there is no sufficient time for the family to come together to plan for calamities or disasters. De Guzman [5] claims that spending time together as a family was also considered a valuable aspect of the family in Filipino culture.

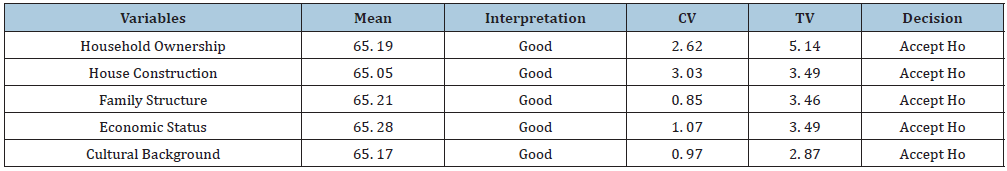

Degree of preparedness according to selected variables

The succeeding tables below present the differences in the degree of preparedness based on the categories of the various variables under study.

Table 4 represents the difference in the degree of preparedness according to the different variables, which includes: household ownership, household construction, family structure, economic status and cultural background. Previous disaster preparedness research indicates that certain demographic variables have a significant influence on preparedness, but the findings below shows no significant differences between the categories of the different variables. The findings may be attributed to the fact families regardless of their structure, accumulated various management of disaster due to previous experiences of such events. Supporting this belief is the historic continuity of institutionally embedded family disaster behaviors that have evolved an adapted themselves to both natural and human-made environmental changes.

Table 4: Differences in the degree of preparedness according to variables.

With regards to disaster preparedness, Person-relative-to-event (PrE) theory posits the importance of personal responsibility is necessary for individuals and populations to form greater behavioral intentions to prepare for disasters such as earthquakes. Person-relative-to-event frames the process of preparing for and responding to a disaster in terms of the interaction between a person variable (appraisals of the coping resources of an individual) and an event variable (appraisals of the magnitude of the particular threat), such that, given coping resources sufficient in quantity and quality relative to the magnitude of a disaster, individuals will engage in more problem-focused (that is, danger control) as opposed to emotion-focused (that is, fear control) coping activities (Table 5).

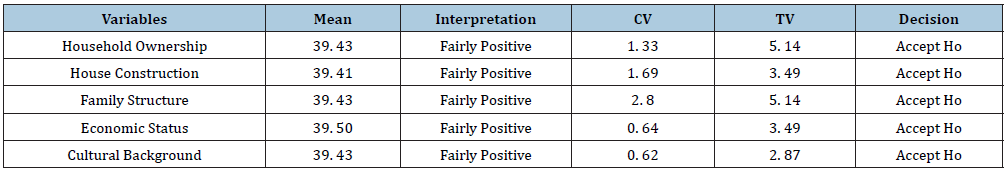

Table 5: Degree of attitude according to variables.

Legend: Highly Positive 43-52; Fairly Positive 33-42. 99; Fairly Negative 23-32. 99; Highly Negative 13-22. 99.

Discussion

Degree of preparedness of families on disaster along selected dimensions

Based on the data, out of 399 participants, only 33% (131 families) have available disaster kit while majority 67% (268 families) do not have. Among the reasons identified include “indifference” which has the highest proportion (37% = 74 out of 200 respondents). They rationalized that “diko pinapansin” (I don’t mind), “walang oras” (time constraints), “forgot” and claims that they have relatives that could help them who are medically inclined and therefore trained for disaster. Many feel it is a waste of time because nothing ever happened to them in the past calamities. Most people believe that they are safe, either calamity will occur or not thus resulting to not taking precautionary activity. This unmindfulness to prepare for calamity was supported by Motoyoshi when he found that the reason behind this matter is that people tend to think that natural disaster like flood are periodic phenomenon and it does not occur randomly.

Attitudes of families toward disaster preparedness

Majority of the respondents agree with the statements “The department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) will provide for our needs so the respondents’ don’t have to prepare” and “The government has the primary responsibility to provide materials needed to prepare for any calamity so I do not need to make much effort to prepare for a disaster” (67/399 and 118/399 respectively). This result communicates the reliance of majority of the families to the highly positive (3.32) response of the participants to the idea of taking effort to ensure that that there should be at least one member in our household who is trained in first aid or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and finding it important to talk about preparing for any disaster or calamity (3.19) are good signs that families can be relied on.

Lastly, obtaining the lowest mean (3.03) among the positive statements, 61.40% of respondents believe that their community has good leadership support and resources to implement disaster preparedness program. The remaining 38% though believed that there is an inadequate leadership skill in their barangay.

Degree of preparedness according to selected variables

The collected experiences from disasters makes the disaster preparedness became a part of each family’s normative framework and thus is able to generate behavioral cues to prompt actions, some of which have become clearly associated with disasters. The findings may also be attributed to the fact that families irrespective of what structure they have, would come up to an agreement during a disaster in order to ensure that lives will be saved. This is supported by General consensus of the family’s significance in determining disaster behavior is achieved during a disaster according to systematically and empirically derived evidences. And lastly, the findings may be attributed to the fact that disaster response is indigenous to family social processes. Intuitively, the family as a social mechanism promotes resilience and increases the capacity for survival, initially from actions taken during disasters. These imply that it is crucial to give more attention to each family’s particular internal family related social processes which include family social networks and gender role obligations than the structure itself, and to include diverse family households in the disaster management process.

People who live with small children and/or individuals with disabilities are more likely to indicate a higher level of preparedness. Other variables, such as education, income, and the perception of vulnerability, also tend to predict preparedness [6-17]. A number of other important psychological variables-such as key attitudes and beliefs-are likely to be useful in not only predicting but also marshalling people’s willingness to prepare them for a disaster. Factors that the public considers in reacting to a disaster warning include the significance of and understanding of the threat, and confidence (or lack thereof) in authorities. Initially, people make the determination whether or not the threat is real, and they trust the source of information before taking action [18-27].

Degree of attitudes according to selected variables

The data showing that the attitude toward preparedness is weak, it may be difficult to change how the population perceive coming disaster. There are many different ways to promote disaster preparedness but, the attitude could be modified through targeting how the people think towards disaster so that they are more likely to take action by emphasizing the potential loss, if the community people are prepared. Changing the way, the community thinks can influence how each individual feel about disaster preparedness and disaster and in turn change the behavior towards prepping for disaster [28-31].

Limitations of the Study

A number of important limitations need to be considered. First, the current study has only assessed the degree of preparedness of the families in high land area which is prone in disaster as compared to low land areas. The knowledge and attitudes of families between people in high land and low land are different. Second, the researchers chose only some areas in Baguio City to conduct this study, therefore the findings of the study do not reflect the preparedness of the whole residents of the city of Baguio. Third, the researchers excluded some part of the questionnaires that the respondents failed to answer some of the demographic items, this is the reason why some of the number of respondents per variables of this study are not consistent. Fourth, since the researcher utilized questionnaire as the primary data gathering tool, there is no assurance that the respondents answered the items genuinely [32-36].

Conclusion and Recommendations

Based on the above findings, the following are the conclusions:

A. Families still cannot adequately respond to disaster, with several areas needed to be enhanced.

- Majority of the families do not find it necessary to prepare disaster supplies ahead of time. Several still don’t see the need to do so.

- Families still need to come together to agree on what to do in case of disaster.

- Not all are ready to respond to earthquake.

- Families are knowledgeable enough on how to respond to typhoon and landslide.

- There is a need to enhance training on disaster response and basic life skills.

B. Families have some negative perceptions related to disaster preparedness.

C. The selected variables do not significantly influence degree of preparedness and attitudes toward disaster preparedness.

D. Attitudes toward disaster do not influence much the degree of preparedness of families on disaster. In terms of disaster, they just have to do what can be done regardless of whether they have negative perception of things. Negative beliefs can be set aside in disaster situations [37-39].

Based on the findings and conclusions, the following are the recommendations

- CDRMC still needs to do much campaign to fully prepare families in response to disaster/calamities. Enhance campaign on disaster preparedness with focus on family’s provision of basic resources, having disaster plan, earthquake response and participation in disaster skills training. Disaster drills should involve families and entire community, not only schools and offices. Activities and programs should be developed that will allow the participation of the whole city not only students. Continue and sustain knowledge enhancement, conduct disaster skills enhancement with focus on CPR.

- Future researchers to explore factors that contribute to negative attitudes toward disaster preparedness like personal-related and government-related factors.

Campaigns on disaster preparedness should cut across any socio-cultural status. People should be understood in the context of their experience [40].

References

- UNESCAP (2015) Overview of natural disasters and their impacts in Asia and the Pacific, 1970-2014.

- (2015) Economic and social survey of Asia and the Pacific. ESCAP, USA, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030.

- Polit D, Beck CT (2018) Essential of nursing research. (9th Edn), Philadelphia, USA.

- Guzman JD (2011) Family resilience and Filipino immigrant families: Navigating the adolescence life-stage.

- Eisenman DP, Wold C, Fielding J, Long A, Setodji C, et al. (2006) Differences in individual-level terrorism preparedness in Los Angeles County. Am J Prev Med 30(1): 1-6.

- Al rousan TM, Rubenstein LM, Wallace RB (2014) Preparedness for natural disasters among older us (placeholder 1) adults: A nationwide survey. Am J Public Health 104(3): 506-512.

- American Embassy Quito (2010) Family natural disaster preparedness and survival.

- American Medical Association/American Public Health Association (AMA/APHA): Improving health system preparedness for terrorism and mass casualty events.

- Austin DW (2012) Preparedness clusters: A research note on the disaster readiness of community-based organizations. Sociological Perspectives 55(2): 383-393.

- Bankoff G (2007) Living with risk; Coping with disasters hazard as a frequent life experience in the Philippines. Philippines, USA.

- Bascos M, Laoingco J (2012) Knowledge and attitude of community folks on disaster preparedness in selected barangays of baguio city.

- Berg R, Hemphill R, Abella B, Aufderheide T, Cave D, et al. (2010) Part 5: Adult basic life support: 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122: 685-705.

- Briones R, Danilo I (2014) Disasters, poverty and coping strategies: The framework and empirical evidence from micro/household data - Philippine case. Philippine institute for development studies.

- Christensen JJ, Richey ED, Castañeda H (2013) Seeking safety: predictors of hurricane evacuation of community-dwelling families affected by Alzheimer's disease or a related disorder in South Florida. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 28(7): 682-692.

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/my.html

- Disaster Risk Reduction (2018) Information sheet international disaster law project center for criminal justice & human rights. The Irish Red Cross Society.

- Derby R, Beutler A (2015) General principles of acute fracture management.

- Do AJL (2012) Disaster preparedness and medical response: It's global responsibility. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 6(1): 13.

- Kaji AH (2019) Emergency first aid priorities. The Merck manual.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (2012) Are you ready? An in-depth guide to citizen preparedness.

- Galindo R, Villanueva G, Enguito MRC (2014) Organizational preparedness for natural disasters in Ozamiz city, Philippines. Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 3(1): 27-47.

- Ishii M, Nagata T (2013) The Japan medical association's disaster preparedness: Lessons from the great east Japan earthquake and Tsunami. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 7(5): 507-512.

- King MA, Dorfman MV, Einav S, Niven AS, Kissoon N, et al. (2015) Evacuation of intensive care units during disaster: Learning from the hurricane sandy experience. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 10(1): 20-27.

- Kozu S, Homma H (2014) Lessons learned from the great east Japan earthquake: The need for disaster preparedness in the area of disaster mental health for children. J Emerg Manag 12(6): 431-439.

- Browne L (2015) Disaster relief: Restricting and regulating public health interventions. J Law Med Ethics 43: 45-48.

- Lincroft NJ (2013) Prepare you college-bound students to deal effectively with a disaster.

- Math SB, Nirmala MC, Moirangthem S, Kumar NC (2015) Disaster management: Mental health perspective. Indian J Psychol Med 37(3): 261-271.

- Najafi M, Ardalan A, Akbarisari A, Noorbala AA, Jabbari H (2015) Demographic determinants of disaster preparedness behaviors amongst Tehran inhabitants, Iran. PLOS Currents Disasters.

- Pajooh EM, Aziz KA (2014) Investigating factors for disaster preparedness among residents of Kuala Lumpur. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci Discuss 2: 3683-3709.

- Muttarak R, Pothisiri W (2013) The role of education on disaster preparedness: Case study of 2012 Indian ocean earthquakes on Thailand's Andaman coast. Ecology and Society 18(4): 51-67.

- Ozlekin SD, Larson EE, Yuksel S, Altun UG (2015) Undergraduate nursing students' perceptions about disaster preparedness and response in Istanbul, Turkey, and Miyazaki, Japan: A cross-sectional study. Jpn J Nurs Sci 12(2): 145-153.

- Michael PA (2015) Hurricane Study: Disaster Preparedness, and the Recovery Model. Am J Occup Ther 69(4): 1-10.

- Public Safety Canada (2010) Earthquakes: What to do?

- Ronan KR, Alisic E, Towers B, Johnson VA, Johnston DM (2015) Disaster preparedness for children and families: A critical review. Current Psychiatry Reports 58:

- Sakashita K, Matthews WJ, Yamamoto LG (2013) Disaster preparedness for technology and electricity dependent children and youth with special health care needs. Clinical Pediatricians 52(6): 549-556.

- Gazette S (2016) Saving lives - why learning first aid skills is important.

- The Hawaiian web masters. The 1990 Baguio city earthquake.

- The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2016) Law and first aid promoting and protecting life-saving action.

- Zotti ME, Williams AM, Wako E (2015) Post-disaster health indicators for pregnant and postpartum women and infants. Matern Child Health J 19(6): 1179-1188.

© 2020 Abdel Carlos. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)