- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Expectations about Motherhood: Its Influencing Factors during Pregnancy

Elizabeth Emmanuel1 * and Jing Sun2

1 Senior Lecturer, School of Health and Human Sciences, Australia

2 Associate Professor, Gold Coast Campus, Australia

*Corresponding author: Elizabeth Emmanuel, School of Health and Human Sciences, Australia

Submission: March 28, 2019Published: July 16, 2019

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume5 Issue2

Abstract

Problem: Maternal expectations and influences on social functioning during pregnancy has received little recognition.

Background: For many women, expectations are developed as part of the adjustment to motherhood. Often little attention is given on how to cope with their expectations which can sometime affect their functioning. Protective factors can cushion this effect and alter the experience for mothers and therefore influence one’s quality of life

Aims: The aims of the paper are twofold. First, to identify the relationship between maternal expectations and health related quality of life during pregnancy. Second, to examine reduced maternal distress, as a protective factor against the effects of high maternal expectations on health-related quality of life.

Methods: A cohort study design was employed. Recruitment was conducted at antenatal clinics at three publicly funded metropolitan hospitals. Variables measured included maternal expectations, maternal distress, social support and the various components of health-related quality of life. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to investigate the relationships.

Findings: Maternal expectations were significantly related to both physical and mental health related quality of life. When added in the regression model, maternal distress had a mediating influence on the relationship between maternal expectations and many components related to health-related quality of life. Reduced maternal distress can influence expectations in a positive way and improve various related quality of life aspects for the mother.

Discussion/conclusion: Maternal expectations are part of the role development process that women go through during pregnancy. Encouraging expectant mothers during the prenatal period to reflect on their expectations and how these influence their emotional experiences and social functioning need to be part of midwifery care.

Keywords: Midwives; Distress; Mothers; Social support; Quality of life

Introduction

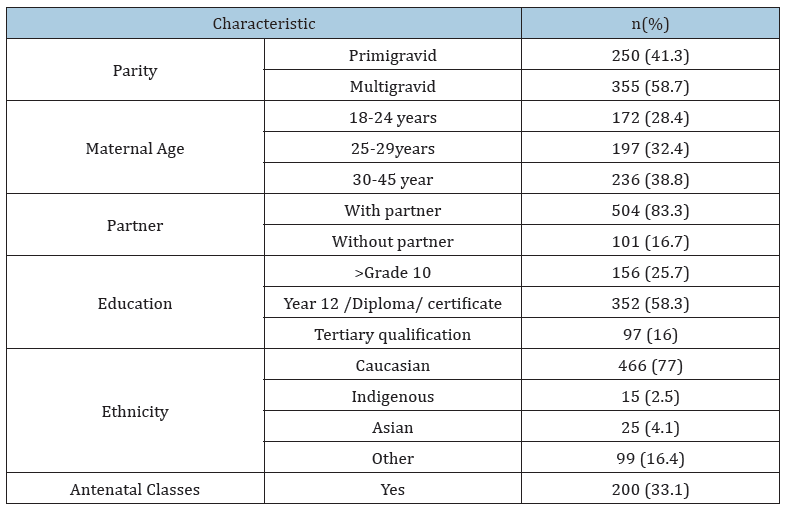

Table 1:Demographic characteristics.

Motherhood can bring new and increased pressures and challenges for women during pregnancy, which can compromise their functioning capacity (Table 1). This can be made worse when mothers are working, caring for children or even having certain expectations during the pregnancy. As family trends are changing, with more women coming from single or blended families, health professionals need to be more mindful of these effects on pregnancy and its effect on the Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) for women. Affected HRQoL, expressed as mental and physical wellbeing, social and role achievements and social functioning and performance [1], may lead to adverse consequences in the transition to motherhood.

Preparation for motherhood takes place during pregnancy, a time of waiting during which expectations are developed. Rubin [2] reports this as a time of excitement, anticipation, planning and visualization of the maternal role and all it entails, so that progressive adjustments in the mother’s life can take place. In achieving these expectations, a mother derives a sense of control that gives her satisfaction, with the adjustment processes allowing her to transition to motherhood smoothly. However, expectations can be realistic or unrealistic, and expectations can be met or not met. When reality is not how the mother imagined the experience to be, this can be destabilizing and sometimes lead to potential cascading negative effects [3].

Contemporary childbearing is marked by a greater appreciation of the role and activities exclusive to mothers. In first world countries, prevailing trends such as greater decision-making abilities about fertility and social circumstances like employment, flexibility with maternity leave, childcare arrangements, financial assistance and birthing have increased women’s opportunities to prepare for the transition to motherhood [4]. As a result, it can be assumed that women have higher maternal prenatal anticipations and expectations than in previous decades.

Maternal expectations were first described by Rubin [2] as a visualisation of the maternal role that takes place in pregnancy and entails the cognitive and behavioural processes labelled as replication, fantasy and dedifferentiation. Further work in this area has been sparse, although there is much debate in the popular literature about the myths around motherhood that feed expectations, such as that motherhood and happiness are synonymous and that love for the baby is instinctive [5]. Other work on maternal expectations relate primarily to health services [6], parenting [7] and first-time mothers [8]. In this latter study, the focus was on middle class women from a homogenous community in the United States. Findings showed a strong relationship between prenatal expectations and postnatal perceptions about becoming a mother.

Few studies have reported prenatal maternal expectations from the perspective of the maternal role development. Of these, Staneva & Wittkowski [9] reported a qualitative study of Bulgarian women (n=10). Results identified four themes, which included expectations of motherhood, self-efficacy, mother-infant interaction and support. Mothers who had unrealistic expectations tended to have a more difficult postnatal adjustment. The findings of this study, however, relied on recall, and the time of interview varied widely between soon after childbirth and 18 months postpartum. Delmore-Ko et al. [10] undertook a mixed method study and investigated 70 couples who were interviewed in the third trimester of pregnancy, and who also completed questionnaires at this time as well as at 6 and 18 months after childbirth. Results showed that women could be sorted into three main clusters based on the nature of their expectations: ‘fearful’, ‘complacent’ and ‘prepared’. Women whose expectations showed a sense of preparing, transitioned to parenthood better while those who leaned towards complacency seemed indifferent to new parenthood.

Adjustments during the transition to motherhood imply social functioning and performance. Much has been reported about these through HRQoL studies during the perinatal period [11]. Of particular interest is the study by Nicholson et al. [12] which investigated the association between depressive symptoms in early pregnancy and HRQoL among North American women. Results showed that women with depressive symptoms had a significantly lower HRQoL. Similar results were reported by Da Costa et al. [11] for depression and life stresses. These factors implied that reduced life stresses and the absence of depression have a protective/cushioning effect on mothers and so enhance the HRQoL. Despite such findings from previous studies, the evidence does not provide a model that explains the influencing effect of maternal expectations on HRQoL and the buffering effects of protective factors factor such as low levels of maternal distress during pregnancy. Therefore, in line with the evidence, this paper provides a model that could demonstrate how reduced maternal distress can enhance the effect of maternal expectations on HRQoL and provide a better understanding by health professionals on how women are adjusting to new parenthood.

The model used in this paper to explain the mediating factors of maternal distress on HRQoL in pregnant women is that proposed by Baron and Kenny [13]. When applied, the model implies that the initial variable (maternal expectations) influences the outcome variable (HRQoL). Thus, the pathway can be said to directly influence the outcome. This pathway, however, can be affected when mediating variables (protective factors) are introduced, which then alters the outcome. The mediating variables then can be said to have an intervening or enhancing effect on the outcome.

This model can take into account the protective factors of low levels of maternal distress and support provided by partners, family and friends. Protective factors tend to lower the negative influences that might put the mother at risk during the transition to motherhood [14,15]. A successful and smooth transition to motherhood can be described as handling the pressures and challenges during the perinatal period amid protective factors that surround the mother, specifically enhancing her ability to deal with potential risks so that she can continue with the mothering process [2]. Risk factors such as high maternal distress have been described as a common phenomenon that occurs during the perinatal period, and poor social support can jeopardise the pregnancy experience for women and, therefore, interfere with smooth transition to motherhood [16]. Studies have shown that minimal distress can protect and enhance the mothers’ experience even when they have to contend with adverse situations such as maternal complications and financial hardships [17].

Maternal distress is a broad concept that covers maternal emotional wellbeing and includes depressive symptoms [18], perinatal depression, anxiety, stress, distress and unhappiness [19]. Some studies have shown a link between maternal distress and adjustment to the maternal role during the perinatal period [20]. Contributing factors affecting this transition have been well studied [16]. Of these, social support has been shown to be highly valued by mothers. Researchers have shown that when women feel supported by family, friends and health professionals, they are more inclined to establish personal competencies, have better coping skills, feel in control and are less likely to feel stress and distress [21]. However, although there is much published about maternal distress, there is little evidence that tells us about its influence on HRQoL for women during pregnancy, and how it can operate as a buffering influence on maternal functioning.

Since a high level of maternal distress has been associated with a difficult transition to motherhood, it can be said that the two variables would work together in relation to HRQoL. This means that when maternal distress is high, maternal expectation is also high, and a difficult transition is more likely to occur. In consideration of the possible relationships between the above variables, the aims of this paper were twofold. First, to identify the relationship between maternal expectations and health related quality of life during pregnancy. Second, to examine reduced maternal distress, as a protective factor against the effects of high maternal expectations on health-related quality of life. This study is part of longitudinal prospective cohort study investigating the relationship between maternal distress and maternal role development among Australian women. It provides an opportunity to explore the effect of maternal expectations during pregnancy and the effect of reduced maternal distress as a mediating factor.

Methods

Research design

The research is part of a prospective cohort study targeting three public hospital antenatal clinics.

Sample/participants

Women in late pregnancy attending the antenatal clinics were invited by the author (EE) to participate in the study. Participation required women to be 18 years of age and over, English speaking and anticipating a healthy term infant at birth. Potential complications in the antenatal, intranatal and postnatal period-such as perinatal death and severe psychiatric conditions-formed the exclusion criteria. A total of 630 women were approached, and of these, women did not complete the survey. The required sample size (n) was calculated to be 593 [22] (confidence interval 95%) from power analysis using the parameters of α level set at .05 and effect size of 0.3.

Data collection

Data were collected at 36 weeks gestation, as part of prospective study. Aspects of the study has been reported in earlier publications [17,23]. Participants completed a questionnaire at the clinic, which comprised socio-demographics information, as well as standardised measures.

Validity and reliability

Demographic variables included age, education level, marital status, length of relationship, employment status and parity. Obstetric information relevant to the perinatal period was also collected and included date of first antenatal visit, whether childbirth education classes were attended, and the nature of their use of health services during pregnancy.

Instruments

The Prenatal Maternal Expectations Scale (PMES) 8 is a 46-item Likert scale and was used to measure the nature of prenatal expectations regarding the infant and maternal roles. The added scores give a possible range of 46 to 230. Low scores on the instrument denote unrealistic negative expectations, while high scores are believed to be representative of unrealistically positive expectations. Scores falling in the middle range are expected to be indicative of realistic expectations. Five subscales are identified. The first subscale, ‘Baby’, examines the anticipated characteristics of the baby and childcare and covers 10 items. ‘Enjoy’, as the second subscale, identifies the degree of enjoyment expected in association with mothering role and activities. The third subscale, ‘Friends’, deals with probable changes in the woman’s relationship with her partner and other friends. The fourth subscale, ‘Life’, explores the likely changes in the woman’s lifestyle or quality of life. And the last subscale, ‘image’, addresses the woman’s projected image of herself as a mother. A high level of Cronbach’s alpha was reported at 0.80 8.

Symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [24] comprising 10 items. Each item is scored on a four-point scale (0 to 3), the minimum and maximum total score ranging from 0 to 30, respectively. Designed as a screening tool, the EPDS does not diagnose clinical depression but provides an indication for further investigation. The actual cut-off scores are determined by balancing sensitivity (proportion of depressed women correctly identified), specificity (proportion of non-depressed women correctly identified) and positive predictive value (proportion of women above cut-off score who are actually depressed). This tool has been used to identify levels of maternal distress by providing cut-off scores along a continuum of normal to distressed responses [25].

HRQoL was measured using the Short Form 12 (SF-12) Health Survey 1. Purposely designed to evaluate HRQoL and monitor outcomes in general and specific populations, the 12 questions are aggregated into two summary scales: the physical (HRQoL-physical) and mental (HRQoL-mental) summary scales. From these two summary scales, eight dimensions were derived from the SF-36, and include physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning emotional role and mental health. Five levels of response choices are set, which add up to a total score of five for each item. Raw scores from the SF12 were transformed to a 0 to 100 scale to establish the standardised HRQoL scores 1. A higher score indicates a higher level of HRQoL. To facilitate the interpretation of scores, mean and standard deviation scores were measured against the ‘SF-36 Population Norms for Australia’ [26].

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the jurisdictions covering the hospital, and from the university. This approval included reporting on the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status of women. Participants provided written consent and were ensured that they could withdraw at any time with no harmful consequence to their care.

Data analysis

All data were entered into SPSS 17.0 for Windows. Random checks of the original data against the computerised data file and crosschecks against the three time periods were also completed and any manual data entry errors corrected. Because maternal expectation and HRQoL are continuous variables, linear regression models were used to analyse the relationship between maternal expectation and HRQoL. In the initial unadjusted models, all maternal expectation components were independent variables, and each component of HRQoL was a dependent variable. In the adjusted models, all maternal expectation components were independent variables, and each component of HRQoL was a dependent variable, and maternal distress, age, education, partner status, parity and length of relationship as confounding factors were controlled in the models. As there were eight components of HRQoL, there were eight unadjusted linear models, and eight adjusted linear regression models.

Result

A total of 605 women participated in the study. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. In this part of the study, women who had not completed fully either of the standardised tools were removed, thus leaving a final sample of 363 women. No significant differences were found between those who completed and not fully completed the standardised tools.

Table 2:Descriptive results of maternal expectations, health related quality of life and maternal distress.

Total scores for maternal expectations ranged from 58 to 162 out of a possible 230. High scores (124 and above) were indicative of unrealistic positive high expectations and low scores (58 to 98) represented unrealistic negative expectations. Descriptive results in Table 2 show the five subscales of maternal expectations, including mean scores and range. The data on these subscales were all normally distributed.

Measures for maternal distress revealed a mean score of 8.80 (SD=4.70). About 21% of women scored between 10-12 (indicating moderate distress), and 20% of women scored above 12 (indicating high distress). HRQoL scores identified eight dimension of health, which were summarised into a physical summary component (M=58.5, SD=19.5), and a mental health summary component (M=65.6, SD=17.1). These measures fall below the Australian population norm for the appropriate age group [26].

HRQoL variables, as independent variables are normally distributed are normally distributed (Table 2) and there are no multicollinearity among the independent variables and no homoscedasticity. Table 3 presents results relating to the relationship between maternal expectation and HRQoL in the physical health domain. The results demonstrate that there is a significantly negative association between expectations relating to friends (p<0.05) and the changes to be made in their relationships, as well as life changes (p<0.01) as a result of pregnancy and childbirth and role limitations (p<0.001) due to physical health problems of motherhood in the initial model. When maternal distress was added in the model, only expectations relating to friends was shown to be associated with role limitations (Regression coefficient β=-.560(-1.1, -0.0), p<0.05) due to physical health problems.

Table 3:Linear regression analysis of the effect of maternal expectation on health related quality of life (physical health domain).

Maternal expectation about the anticipated joy the baby would bring was found to be negatively related to general health (p<0.05) in the initial model. When maternal distress was added in the model, the relationship between anticipated joy and general health became non-significant, suggesting maternal distress mediated the relationship between maternal expectation relating to joy and general health. When maternal distress was added in the adjusted model, the negative association between expectations relating to friends and the changes to be made in their relationships as a result of pregnancy and role limitations due to the physical health problems of motherhood remained significant. This suggests the negative relationship of expectations is explained by the effect of maternal distress.

Table 3 presents results of the relationship of four components of the mental health domain of HRQoL and maternal expectations. The results in the initial models demonstrate that expectations about changes in one’s lifestyle were negatively related to social functioning, emotional role and mental health. In addition, expectation relating to friends and the changes to be made in their relationships as a result of pregnancy and childbirth was negatively related to mental health. When maternal distress and social support were added in the model, all associations with maternal distress became significant, suggesting maternal distress is mediating the relationship between maternal expectations around lifestyle changes and social functioning, emotional role and mental health, and the relationship between expected changes in relationships between friends and mental health.

In conclusion, maternal expectations have a direct and significant effect on HRQoL in the physical domain, which includes physical role and general health; in the mental domain, this includes social functioning, emotional role and mental health. When there is decreased maternal distress, this has a mediating effect on the influence of maternal expectations on HRQoL. In particular, this is most notable in one physical health domain (general health) and all mental domains except vitality within HRQoL.

Discussion

Maternal expectations in this sample of Australian women indicate that anticipation about the baby, enjoyment, friends, life and image during pregnancy is relatively common. The study’s findings are in contrast to Coleman et al. [8] study and may be related to the inclusion of both primigravids and multigravids, who may have or may not have attended childbirth education classes. The present study also had a larger cohort of women from Australia. Unlike the sample in the aforementioned study, this sample had participants from varied educational levels and a broader age range. This sample is, therefore, more reflective of the general population of childbearing women who use the public maternity health services [27].

Recent studies tend to focus on expectations and reality and how this affects a mother’s adjustment to the maternal role. Staneva et al. [9] emphasised that when there were incongruencies between expectations and reality, mothers had difficulty adjusting to their new role. Delmore-Ko et al. [10] highlighted that smooth adjustment relied on the level of anticipation and preparedness of the mother. Both studies were qualitative in nature, providing acknowledgement of maternal expectations as an important concept in the perinatal period. The present study adds to this knowledge base using a quantitative approach and a larger sample to identify the effect of maternal expectations on HRQoL. In particular, the study examined the different aspects related to quality of life and significant factors that could enhance the experience for mothers.

Two significant findings were identified in the present study. First, for many mothers, expectations regarding friends (e.g. sharing continued common interests) had a negative influence on physically taking on the role of a new mother, and the anticipated joy of having a baby had a dampening influence on a mother’s general health. This suggests that coming to terms with the reality of new motherhood can be challenging, therefore making it difficult to adjust motherhood. Disappointment and disillusionment may contribute towards lower HRQoL. It is very possible at this stage that a mother goes through what Lederman & Weis [28] describe as ambivalence-that is, the mother anticipates and prepares for motherhood, yet at the same time feels uncertain about the relationships she has with her partner, friends and others and what she would have to give up or strengthen.

Thus, physically assuming the new role as mother it would seem does not fit comfortably. Similarly, the anticipated joy of having a baby tends to be incongruent with the physical changes that the mother is going through, which are not only demanding but often uncomfortable and tiring. Although Lederman & Weis [28] identified this as an issue that tends to occur in the first trimester, these findings would suggest that HRQoL is affected even in later pregnancy. The mental health domain in HRQoL similarly showed that expectations related to lifestyle changes and social functioning, taking on the persona of mother and maintaining mental wellbeing was challenging. Several studies confirm that mothers frequently experience distress during this time when expectations abound [9]. Indeed, mothers in first world countries frequently struggle with the notion of being the perfect mother who needs to feel fulfilled and filled with happiness and yet has to deal with everyday hassles of living within their personal circumstances and context.

The second major findings of this study showed that reduced maternal distress had a mediating influence on maternal expectations and a concomitant effect on the various components of HRQoL. These findings confirm that maternal distress is prevalent during the latter part of pregnancy. In addition, the minimising of maternal distress can be of significant benefit towards mothers achieving their expectations, which then affects quality of life.

These results suggest the importance of considering levels of maternal distress and ways in which these can be reduced so that mothers can effectively meet their expectations. Rubin [2] reported that when expectations are not materialised, dissonance and self-doubt occurs, and sometime a sense of failure. Thus, when expectations are met, which is enhanced by reduced stress and confusion, mothers are better able to prepare, orientate and organise themselves during pregnancy. As a result, functioning capacity during the transition to motherhood is improved.

Our study findings highlight that mental and physical aspects of HRQoL in pregnant women are negatively influenced by high levels of maternal distress. These findings are important as lowered physical and social functioning during pregnancy is reported to be associated with increased risk of premature births [29]. Diminished emotional functioning has been related to increased uses of maternal health services [30]. Mothers with high levels of maternal distress show a diminished capacity of functioning in their new role as mother [17]. Such findings can assist health professionals during screening in the antenatal period by taking time to ascertain mothers’ expectations during this period and encouraging them to verbalise these.

For instance, a midwife can discuss with the expectant mother the ambivalence of making changes in her life in regards to relationships with partners and friends. Antenatal education programs can include in their discussion on the realities of parenthood, examples of special moments, as well trying moments. Midwives can encourage women who are struggling to liaise with the community perinatal mental health nurse should this service be needed. Such a service often involves one-on-one counselling, links to other community services and self-help groups.

Limitations

An important limitation to this study was that completion rates for the tools were lower than expected. It is possible that participants were experiencing some distress or hassles of daily life. In addition, there was no measure in the postpartum period to determine whether the participants’ expectations were met. In addition, when the study extended into the postpartum period, the focus was on maternal role development as part of the transition process to motherhood. Hence, no conclusions can be drawn about maternal expectations, its influence on HRQoL and the mediating effect of maternal distress over time. However, the study results during pregnancy provide a major contribution towards knowledge in this field of study.

Conclusion

The study results provide interesting implications for clinical practice. Health professionals need to take serious consideration of mothers and their expectations during pregnancy as expectations are part of the role development process that needs to take place during the transitions to motherhood. When expectations are disclosed, health professionals have an opportunity to assist mothers differently through tremendous change in all aspects of their life.

Relevance to practice

Adjusting to these changes can be difficult for some women. Enhancing this adjustment can lead to an improved HRQoL through simple measures such as advice, counselling, referral and support. Mothers with specific expectations or few expectations are at risk of lowered HRQoL and perhaps can be identified early by midwives through simple and well-worded questions. These might include the questions: ‘Do you anticipate some changes in your life as a result of the pregnancy?’; ‘Are you having any difficulty with meeting some of your plans during this pregnancy?’ and ‘How are you managing giving up some familiar ways of thinking and doing things?

Such measures not only promote a mother-centred focus but validate to the mother that adjustment to motherhood is a significant milestone. Having expectations is a normal preparation in the transition to motherhood. Health professionals need to be aware that an enhanced HRQoL is needed by mothers during pregnancy so that expectations can be reached, and at the same time need to also be aware of mothers who might be compromised by increased levels of maternal distress. Future research is needed focusing on mothers in different contexts.

References

1. Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner BD, Gandek B (2002) How to score version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey. Quality Metric Inc. Lincoln, Long Island and Health Assessment Lab, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

2. Rubin R (1984) Maternal identity and the maternal experience. (1st edn), Springer Publishing Company, New York, USA.

3. Tiran D (2010) Natural childbirth: maternal expectations versus the reality. Issue Women’s Health.

4. The Office for National Statistics (2008) Social Trends. (38th edn), Macmillan Publishers Ltd, Basingstoke, England.

9. Staneva A, Wittkowski A (2012) Exploring beliefs and expectations about motherhood in Bulgarian mothers: a qualitative study. Midwifery.

14. Arat A (2013) Doulas’ perceptions on single mothers’ risk and protective factors, and aspirations relative to Childbirth. The Qualitative Report.

15. Sawyer J (2011) Mindfulness and self-compassion in the transition to motherhood: a study of postnatal mood and attachment. Columbia University, USA.

22. Macorr Inc (2003) Sample size calculator. http://www.macorr.com/ss_calculator.html

26. Australian Bureau of Statistics (1995) National health survey. SF-36 Population norms. Australia http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs

27. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Social Trends (2008) In: Statistics Abo (Ed.), Canberra, Australia.

28. Lederman R, Weis K (2009) Psychosocial adaptation to pregnancy. (3rd edn), Springer, New York, USA.

29. Goldenburg R, Culhane J (2005) Prepregnancy health status and the risk of preterm delivery. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 159: 89-90.

© 2019 Victoria Hughes. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)