- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Key Components for Successful Nurse Practitioner Student Learning in an International Clinical Setting

Victoria Hughes*, Debbie Busch, Jennifer Trautmann and Elizabeth Sloand

Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, USA

*Corresponding author: Victoria Hughes, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, 525 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 212205-2110 USA

Submission: May 21, 2019Published: June 24, 2019

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume5 Issue2

Abstract

Academic literature contains much information on pre-licensure nursing abroad experiences, but there is a gap in international clinical experiences for Nurse Practitioner students. The objectives of the international clinical practice experience for nurse practitioner (NP) students were to provide high quality and culturally sensitive primary care to clinic patients and to give students the opportunity to participate as team members and enhance their skills as primary care providers in an international rural underserved setting. Pre-planning meetings, supply coordination, and post-trip reflections resulted in student development of culturally sensitive health care practices and contribution to a sustainable medical mission. Further inquiry into the student’s global and clinical reflections were studied using qualitative methodology to explore themes from the students’ experiences. The clinical practicum at the Haiti mission clinic demonstrates a lasting international academic healthcare partnership and a clinical practicum opportunity for primary care nurse practitioner students.

Background

International study and learning experiences can be a valuable adjunct to nursing education and can be found among several nursing programs in the United States, although almost all of the literature focuses on pre-licensure opportunities. An international health care setting can promote nursing students’ developing global cultural awareness [1-3]. Some advantages for international study experiences include the development of cultural competence and global awareness [3]. Global clinical experiences can be a life-changing event. Many students living and raised in America are unaware of the extreme differences in socioeconomic conditions experienced by others, as nearly 800 million live in extreme poverty around the world [3].

Johns Hopkins School of Nursing faculty has been continuously refining the program and process of taking both pre-licensure and advanced practice students to Haiti for the past 20 years. The objectives of the international clinical practice experience for nurse practitioner (NP) students were to provide high quality and culturally sensitive primary care to clinic patients and to give students the opportunity to participate as team members and enhance their skills as primary care providers in an international rural underserved setting. The purpose of this report is to describe our experiences in developing and utilizing an international clinical practice site in a medically underserved rural area of a Caribbean country for primary care nurse NP students. The program evaluation project was approved by the Johns Hopkins University IRB.

Method

Student selection

Nurse practitioner (NP) students enrolled in the primary care adult-gerontology, pediatric, and family nurse practitioner programs received information about the international clinical opportunity and were invited to apply. The initial communication about the experience included a description of the clinical experience, student responsibilities, expected clinical hours that would fulfill their NP practice hours, and personal living conditions (community living with dorm-style sleeping arrangements and basic meals cooked by local hosts). To be eligible students must be in their second year of clinical practice courses and current unhindered registered nurses (RNs). Ideally, having a mix of student academic-tract specialties and variation of travel and international practice experience added to the students’ experience and team dynamics.

The application process included a brief essay about the student’s interest, perceived strengths, and learning goals for participating in the international clinical practice experience. Faculty members reviewed applications and personal interviews were performed as necessary. Selected students were required to attend two in-person briefings to learn about trip logistics, professional responsibilities, clinic protocols, packing suggestions, and other country specific details.

Setting

The clinic was located in a rural mountain village in southwest Haiti. A cement block building housed a pharmacy, administrative offices, intake area, storage closet, an open clinic bay, and porch areas that could be transformed into isolation areas as needed for cholera or other outbreaks. The visiting US-based interprofessional team included five NP students, four nurse faculty members, one physician, one medical resident, two registered nurses, a logistics coordinator, and a referral assistant. Three of the nurse practitioner faculty provided direct patient care within their NP scope of practice and adhering to established clinical practice guidelines for available treatment, medicine, and referral consistency. One nursing faculty member focused on maintaining daily operations, pharmacy and supply, patient flow, and leadership insight for the students.

All of the visiting medical team members provided patient care within the open bay section of the building, with nursing triage conducted by the NP students on the covered porch.

Coordination

The Haiti trip was coordinated in collaboration with St. Francis Church, a local U.S. faith community that is connected with the Parish Twinning Program of the Americas, a Catholic nonprofit organization. St. Francis has been “Twinned” with St. Paul’s parish in Leon, Haiti, for more than two decades. One nurse faculty member has been participating in Haiti medical mission trips with this organization for 20 years. A donor, who has a combined interest in nursing education and health care in Haiti, provided partial funding for the trip. A school of nursing grant provided additional funding. Team members were guests of the local church community and stayed together in a church-owned building that is within the community and in short walking distance of the clinic. This added to the students’ immersion experience and understanding of the patients they served.

Analysis

The NP student journal reflections, daily debriefings and faculty/student feedback discussions were utilize to evaluate the effectiveness of the international clinical practice experience. Students were asked to write a reflection based on a 7question survey (Figure 1). Survey data were anonymized before analysis was performed. Four researchers independently performed thematic analysis. We began the thematic analysis with immersion in the data by all researchers, reading and re-reading student reflections. Early identification of subthemes pertaining to different aspects of student experience across the data, followed by axial coding to draw out connections between the codes and subthemes. Analysis of the relationships between subthemes generated broader themes that captured the wider factors. The final themes resulted from discussion and comparison of individual analysis and agreement from all four researchers.

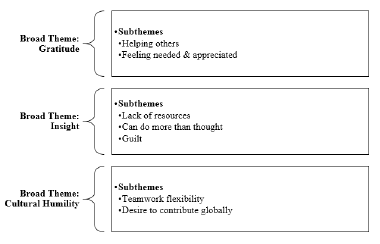

Figure 1:Coding.

Result

There were several strengths of the planning and execution of the NP student clinical experience in Haiti. During pre-trip sessions, the faculty leader provided a description of expectations for accommodations, anticipated modes of travel, limited food options, environmental conditions, clinical practice site overview, recommended immunizations, and disease prevention. Each team member received a detailed packet of information describing ticket & passport requirements, organizational forms to be completed, and travel insurance cards. Students were instructed to enroll in the university travel registry and the U.S. State Department travel registry. Faculty gave additional information to students to further prepare them for the experience including the clinic’s medical treatment protocols and medication formulary, a Haitian Creole phrase sheet and useful Haiti and language websites, baggage requirements, recommended clothing, bedding, personal items, and expected expenses.

Faculty and students were briefed regarding the history of the School of Nursing’s sustained relationship with the Haitian clinic and the importance of flexibility throughout the experience. Faculty led discussion about Haitian history, culture and strategies for providing optimal patient care within the cultural context. Pre-trip sessions helped students and faculty feel prepared for the upcoming trip and their role on the team. The debriefings and student reflections facilitated clinical and cultural learning along with personal insight.

Processes

The pre-trip travel preparation meetings and traveling together as a group helped build team cohesion. While staying at a medical mission hostel in Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti, the students and faculty learned more about each other’s backgrounds and interests. The lengthy travel time (2 days each way from home to the rural site) also provided some quiet time to think and prepare for the clinic days ahead. Hearing about previous trip experiences and challenges helped to formulate team members’ expectations along with reviewing the clinical guideline plan of care for commonly presenting medical conditions; such as hypertension, diabetes and acute infections. Post clinic return travel time allowed for debriefing, reflections, recuperation, and consideration of the challenges of returning to “Normal” life.

Community outreach

Coordinating with the marketing and student services departments, the faculty and students initiated a needed item drive within the school of nursing, university community and a local community running club. Team members gathered donations of toothbrushes, reading glasses, toiletries, medical supplies, and athletic shoes for distribution to Haitian school children and clinic patients. These items facilitated team activities beyond clinical services, including school-based and orphanage-based oral hygiene education and home visits to the homebound. Both activities enhanced student understanding of the local context and community needs and strengths.

Clinic flow

The team cared for approximately 150-200 patients daily at the clinic for five days. Infants, children, adults, pregnant women, and older adult patients with a wide range of chronic and acute health care conditions were seen at the clinic. The creation of an organized triage and patient care flow was essential to meet the patient volume demands. Student NPs and registered nurses rotated through different roles and responsibilities including patient triage, nurse intake, wound care, laboratory testing, pharmacy services, NP student work with clinicians, and floating charge nurse. This rotation contributed to clinic flow and flexibility, smooth teamwork, patient care effectiveness, and appreciation for each team member’s contribution to clinic success. A faculty ‘Charge’ nurse organized the flow and daily schedule.

Faculty and students provided their own equipment such as stethoscopes, otoscopes, and sphygmomanometers. point-of-care testing (i.e., urine pregnancy, HIV, and urinalysis), gloves, and soap. Local interpreters were team members who assisted in patient care visits to facilitate health care providers’ understanding of patient history and symptoms. They assisted throughout each visit including individualized patient education through verbal and written methods with materials that were Haitian. The healthcare team used the local clinic patient medical records for reviewing prior health care at the clinic and for recording the current encounter.

The US based team collaborated with the local registrars, medical records personnel, nurses, physician, pharmacy tech, logistics experts, and housekeeping staff to provide services. Students learned to rely on their basic health assessment skills because the clinic had minimal diagnostic equipment, very basic laboratory capacity, limited pharmacy options, and no radiology.

The healthcare team used written formulary treatment guidelines that included treatment suggestions, referral parameters, and follow-up strategies. The guidelines were developed several years ago for this specific clinic and are reviewed and updated yearly by participating nurse, physician, laboratory, and pharmacist team members in collaboration with local health care providers and leaders. Medications are chosen based on effectiveness and local prescribing patterns and are secured through partnerships with several non-profit agencies in the U.S. Collaboration with the Haitian nurses throughout the day was essential for providing optimum care in the rural Haitian context. The Haitian nurse received referrals for prenatal care, STD/HIV testing, TB testing and care, and monitoring of children at risk for nutritional deficiencies. Team members brainstormed regularly about how to continuously improve clinic processes and patient flow. Students, as full team members, expressed a sense of ownership and responsibility for the functioning of the clinic.

Clinical learning

The medical mission trip was a compelling learning experience. Students were required to maintain clinical logs of patients seen throughout the week of clinical practice. NP students quickly learned to rely on basic assessment skills for determining diagnosis and treatments for patients due to the very limited laboratory and diagnostic services. Students learned to use the medications that were available within the local economy and local health system to promote sustainability and continuity of patient care. Occasionally the formulary medications that were prescribed would vary from what would be typically be prescribed in the U.S., instead of prescribing the ‘newest, latest and pricier’ medication, a safe and economical classic medication would be the best choice within the resource restricted environment. Several NP students commented in their reflections that they were not aware that they could accomplish so much care and

The students were exposed to many patients with acute and chronic health or birth conditions that would have been managed at a much earlier phase within the U.S. With few referral options, scarce medical specialists, and limited options for hospital-based care, the students learned to perform physical assessments in a low-resource clinical environment and to provide the best treatment and care options within the cultural context and with available resources. The NP students learned to consider patient referral triage based on the assessed risk, the available resources, the financial impact, the family impact, and the probability of the patient being able to obtain treatment that would produce a positive health outcome. Scheduled de-briefings to discuss the activities and challenges of the day gave faculty, students, and all team members time to review the complexity of various cases, how a similar case may be managed in a clinical setting in the U.S., and what each member learned, which was also noted as important by Saenz & Holcomb [3].

Student reflections

Three broad themes (gratitude, insight, and cultural humility) and seven subthemes emerged from the qualitative analysis (helping others, feeling needed and appreciated, lack of resources, can do more effective care with less than thought, guilt, teamwork, and connection).

The students expressed overwhelming gratitude for the opportunity to serve the community in Haiti. “It was an honor to serve this community, to be a stranger in their hometown, not speaking their language and have them accept us as their healthcare providers” (participant 5). The subthemes of student gratitude include helping others and feeling both needed and appreciated. “We were never going to be able to treat every patient, and we had to leave after just one week, but the time we spent helping those we could was incredibly meaningful” (participant 4). “The gratitude expressed to us in the week during clinic was so great it was immeasurable” (participant 1). “The Haitian people were extremely thankful and it was a great reminder of the meaning of healthcare” (participant 2). “Discovering how much the people of Leon depended on the clinic we staffed was the most meaningful part about the experience” (participant 3).

The students described many insights that they gained during the medical mission to Haiti. One of the insights involved the level of poverty and the extreme lack of resources. “What was most surprising about the experience was the limited infrastructure of the facility where we worked” (participant 3). “I expected there to be workstations set up, but what I saw was an empty room with two exam tables and a few tables and chairs; it was that moment when I realized our purpose. The reason that I went on this trip was to help people and provide healthcare services to a community that would otherwise go without” (participant 4).

Students discovered that they could do more than they thought without having all of the desired resources. “Most surprising about the experience was how much we could do with so little… we improvised with off-label medication uses for acute illnesses and treated everyone as appropriately as possible” (participant 1). “I was also able to rely more on my physical exam skills for assessments because common diagnostic and laboratory testing was not available” (participant 2). The nursing students expressed a sense of guilt at not being able to do more to help. “It is difficult to return to my work and studies while knowing that the children we cared for in Haiti do not have clean water or proper shoes” (participant 5). “Seeing the benefit of these medical services first hand was a great experience, but it also showed me that more needs to be done” (participant 2).

The final major theme identified from the student reflections was cultural humility with flexible teamwork and desire to serve globally as subthemes. “This was an eye-opening and humbling experience and I am truly grateful that I could spend a week immersed in their culture and environment” (participant 2). “The Haitian culture is inspiring, these individuals will make you feel like having nothing is everything” (participant 4). “In order to provide comprehensive holistic care, it’s vital to have an understanding about where our patients come from, both geographically and culturally” (participant 1). In Haiti, I found it best “to adapt the local mindsets” (participant 1). “I was inspired by the nurse at the clinic in Leon and how she truly was a public health nurse, serving the whole community with minimal resources and still making a difference. This experience reminded me of how capable nurses are and the impact they can have in a community” (participant 5). “I have always known that at some point in my nurse practitioner career I want to spend time working in a developing country…I want to harness all the good that will come from my education and do something meaningful in my practice” (participant 4).

Conclusion

The Haitian clinical experience at our school of nursing is a distinct offering for NP students to learn advanced practice nursing skills in an international setting, requiring the students to ‘stretch’ regarding physical, emotional, and clinical competency. The NP students and newer faculty were first required to familiarize themselves with the host country including Haitian health and social conditions, population bio-demographics, language (short medicalphrases in the host country’s language), geography and history, religious practices, common medical ailments and conditions. In reflective essays, students describe their transformation through the international clinical practice experience, aligning with the mission and goals of our program. This clinical practice experience in Haiti exemplifies a sustainable international academic healthcare partnership that has been ongoing for two decades. It occurs once or twice per year and provides a valuable clinical practice opportunity for primary care nurse practitioner students. Faculty and students embraced the key values of expanding their global perspective and striving for cultural humility [4].

The NP students who participated in the international clinical practice experience expanded their knowledge and skills through exposure to large numbers of acute and chronic patients in a primary care setting. The students honed their skills of physical assessment, participated in the diagnosis and treatment of unfamiliar diseases and conditions that are indigenous to the community, and collaborated within a multinational interprofessional team of providers and professionals. Effective preparation and preplanning meetings helped insure that both students and faculty had a meaningful personal and professional experience and were well prepared to deliver optimal clinical and community health care.

References

- Bentley R, Ellison K (2007) Increasing cultural competence in nursing through international service-learning experiences. Nurse Educ 32(5): 207-211.

- Callen B, Lee JL (2009) Ready for the world: Preparing nursing students for tomorrow. Journal of Professional Nursing 25(5): 292-298.

- Saenz K, Holcomb L (2009) Essential tools for a study abroad nursing course. Nurse Educator 34(4): 172-175.

- Visovsky C, McGhee S, Jordan E, Dominic S, Morrison BD (2016) Planning and executing a global health experience for undergraduate nursing students: A comprehensive guide to creating global citizens. Nurse Educ Today 40: 29-32.

© 2019 Victoria Hughes. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)