- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Health Seeking Behavior among Mentally and Physically Ill Patients: A Comparative Study

Nesrine A Wadie and Naglaa M Gaber*

Faculty of Nursing, Cairo University, Egypt

*Corresponding author: Naglaa M Gaber, Lecturer of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Cairo University, Egypt, Tel: 023645336/01001672841; Email: naglaamostafa4545@gmail.com/eter.love@gmail.com

Submission: May 10, 2018;Published: June 07, 2018

ISSN: 2577-2007 Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

Health-seeking behaviour has been defined as a sequence of remedial actions that individuals undertake to rectify perceived ill-health. Therefore, this study was to assess the barriers affecting seeking health care services as perceived by mentally and physically ill patients. A descriptive comparative design was utilized in this study. A sample of convenience of 100 patients (50 physically ill patients and 50 mentally ill patients) was recruited for the conduction of this study. Socio-demographic/medical data sheet, barriers affecting seeking health care services questionnaire were used for data collection. Findings of this study indicated that, near half of studied sample of patients with mental illness express severe level of difficulties in seeking health care services as compared to more than one third of patients with physical diseases. Meanwhile, more than one third of studied sample of patients with mental illness express moderate level of difficulties in seeking health care services as compared to two thirds of patients with physical diseases. To conclude no statistical difference was found between patients with mental illness and patients with physical disease in relation to barriers affecting seeking health care services. Further studies on a larger number of patients with different diagnoses from different geographical areas are recommended.

Keywords: Health seeking behaviours; Physically ill; Mentally ill

Introduction

Health-seeking behavior has been defined as a “Sequence of remedial actions that individuals undertake to rectify perceived ill-health”. In particular, health-seeking behaviour can be described with data collected from information such as the time difference between the onset of an illness and getting in contact with a healthcare professional, type of healthcare provider patients sought help from, how compliant patient is with the recommended treatment, reasons for choice of healthcare professional and reasons for not seeking help from healthcare professionals [1].

In the broadest sense, health seeking behavior includes all behaviors associated with establishing and maintaining a healthy physical and mental state [2], (Primary Prevention) [3]. Healthseeking behaviors also include behaviors that deals with any digression from the healthy state, such as controlling (Secondary Prevention) and reducing impact and progression of an illness (Tertiary prevention) [4].

The concept of studying health seeking behaviors has evolved with time. Today, it has become a tool for understanding how people engage with the health care systems in their respective socio-cultural, economic and demographic circumstances. All these behaviors can be classified at various institutional levels: family, community, health care services and the state [5]. In places where health care systems are considered expensive with a wide range of public and private health care services providers, understanding health seeking behaviors of different communities and population groups is important to combat unaffordable costs of health care [6].

Depending on illness type, people seek different forms of treatments specific to the disease they are diagnosed with. In addition, depending on the severity of the diagnosed disease, people might select different forms of treatments and medication. It was found that individuals perceived their illness to be either mild or not for medical treatment, which prevented them from seeking healthcare treatment. In addition, poverty emerged as a major determinant of health-seeking behavior as treatments were often perceived as either a waste of money, lack of money, or poor attitude of health worker [7].

The difference between gender roles is significant in the patterns of health-seeking behavior between men and women. According to Currie & Wiesenberg [8], women tend to engage in less health-seeking behavior compared to their male counterparts. Moreover, Currie & Wiesenberg [8] highlights three components a woman’s decision-making process for seeking healthcare. Firstly, women generally are less likely to identify disease symptoms in the first place. Women might shrug of symptoms as normal everyday muscle aches or normal regular occurrence. To be able to recognize and identify a health problem, one needs to have some form of knowledge and awareness of symptoms and illnesses. Secondly, the study reveled that women tend to belief that they are more restricted compared to their male counterparts in terms of health care accessibility.

The current study also highlighted the importance of access issues to health care seeking. These factors involved costs associated with seeking treatment, distance and the time taken to travel to health care facilities. Many people had an issue with finding the funds to use health care or to purchase subsequent treatment. Although this did not stop all people from using health care services, it made a difference to people’s activities, and it made a difference for those trying to follow prescribed treatments, with half saying treatment was too expensive, while others took the route of trying to save money and time by self-medicating [9].

Significance of the Study

Despite the importance of nursing role in assessing factors affecting health seeking behavior, scattered researches were done in this area especially on the national level. As nurses play a pivotal, multifaceted role in the assessment and treatment of patients with different diagnoses; this research could provide nurses and other health professionals with an in-depth understanding related to this topic which could be reflected positively on the quality of patient’s life. Moreover, it is hoped that, findings of this study might help in improving quality of the patient’s care and establish evidencebased data that can promote nursing practice and research

The Aim of the Study

This study aims to assess the barriers affecting health seeking behavior as perceived by mentally and physically ill patients.

Research design

The selected design for the current study is descriptive comparative research design. This type of research design involves one or more group of subjects observed in comparing of each.

Sample

A sample of convenience of 100 patients (50 physically ill patients and 50 mentally ill patients) was recruited for the conduction of this study. According to the following criteria; aged 18 to 60 years, well diagnosed and have follow up schedule, demonstrating no obvious cognitive impairments. The sample size calculating using the power analysis α=0.80 and the effect size based on the previous research studies was 0.5, and the analysis for research questions using paired t. test.

Setting

This study was carried out at two places: Al-Abassia Mental Health Hospital at the outpatient Clinic, and AL Kaser Al-Ani University Hospital at the Out-patients Clinics.

Procedure

The investigators used and followed the back translation procedure for verifying the translation of the tool. An official permission was obtained from the Al-Abassia Mental Health Hospital at the outpatient Clinic, and AL Kaser Al-Ani University Hospital at the Out-patients Clinics to conduct the study.

Each participant was interviewed individually, in semistructured interview, for about 20 to 30minutes, the questionnaires were read and explained, and the choices were recorded by the investigators. The subjects were asked about their sociodemographic and medical data which include, age, educational level, marital status, occupation, no. for admission, duration of disease. Two open questions were asked for the participants to collect their qualitative opinions about barriers they faced when seeking health care services.

Data Management and Analysis

Date was analyzed using statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 20. Numerical data were expressed as mean±SD, and range. Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. For qualitative data, comparison between two variables was done using chi-square test. Comparison between quantitative variables has been done by using independent sample t-test. Probability (P-value) less than 0.05 was considered significant and less than 0.001 was considered as highly significant.

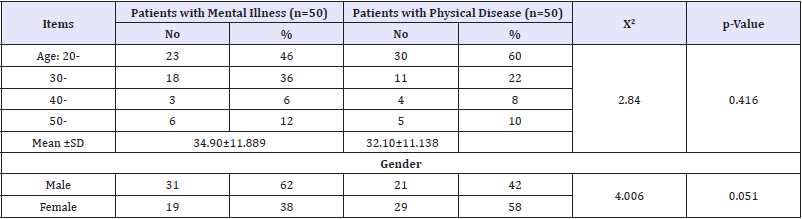

Table 1 revealed that, about half of studied samples (46%) of patients with mental illness aged between 20 years to less than 30 years as compared to 60% of patients with physical diseases with mean age 34.9 of patients with mental illness as compared to of patients with physical diseases. Regarding patient’s sex the table added that about two thirds (62%) were male of patients with mental illness as compared to 42% of patients with physical disease. The table also stated that, there are no statistical significance difference were found between the two groups in relation to age and sex (where X2=2.84, 4.006 at p=0.416, .051. respectively).

Table 1: Distribution of age and gender among the studied sample (n=100).

*significance at p≤0.05.

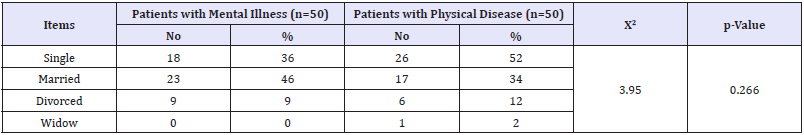

Table 2: Distribution of marital status among the studied sample (n=100).

Table 2 revealed that, about one third of studied sample (36%) of patients with mental disease were single marital status as compared to more than half of studied sample of patients with physical diseases (52%). The table also stated that, there is no statistical significance difference was found between the two groups in relation to marital status (Where X2=3.95, P value=0.266).

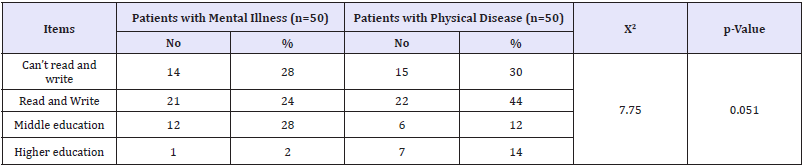

Table 3 stated that, about more than one quarter of studied samples (28%) of patients with mental illness can’t read and write as compared to about near one third (30%) of patient with physical diseases. The table also stated that, there is no statistical significance difference was found between the two groups in relation to level of education, (Where X2=7.75, P value=0.051).

Table 3: Distribution of level of education among the studied sample (n=100).

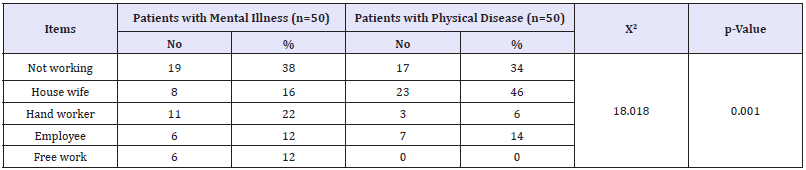

Table 4: Distribution of occupation among the studied sample (n=100).

Significance level at p<0.05.

As observed in Table 4 more than one third of studied sample (38%) of patients with mental illness was not working as compared to more than one third of studied samples 34% of patients with physical diseases. The table also stated that, there is statistical significance difference between the two groups in relation to occupation, (where X2=18.018 at p=0.001).

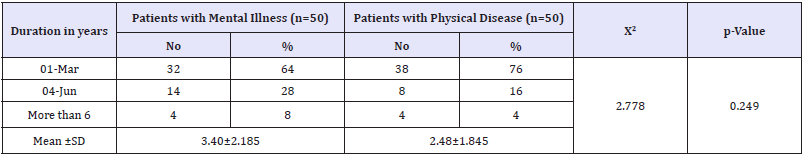

Table 5: Distribution of duration of disease among the studied sample (n=100).

Table 5 revealed that, near two thirds of studied sample (64%) of patients with mental illness have a duration of disease ranged between 1 year to 3 years with mean duration=3.40 as compared to about three quarters (76%) of patients with physical diseases with mean duration=2.48. The table also stated that, there is no statistical significance difference was found between the two groups in relation to duration of disease, (where X2=2.778 at p=0.249).

Table 6 stated that, more than third of studied samples (38%) of patients with mental disorders were from rural areas as compared to near two thirds (62%) of studied samples of patients with physical diseases. The table also added that, there is statistically significance difference was found between the two groups in relation to place of residence (where X2=7.55 at p=0.05).

Table 6: Distribution of Residence among the studied sample (n=100).

Table 7: Presence of health insurance among the studied sample (n=100).

Table 7 revealed that, 80% of studied sample of patients with mental illness a who no health insurance as compared to 30% of patients with physical diseases. The table also stated that, there is no statistical significance difference was found between the two groups in relation to presence of health insurance, (where X2=5.22 at p=0. 07).

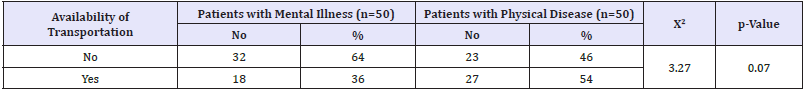

As observed in Table 8 near two thirds (64%) of studied sample of patients with mental illness have difficulty in access the health care facility as compared to near half (46%) of patients with physical diseases. The table also added that, there is no statistical significance difference was found between the two groups in relation to availability of transportation to health care facility, (where X2=3.27 at p=0. 070).

Table 8: Availability of transportation to the health care facility among the studied sample (n=100).

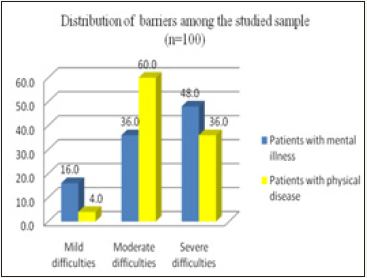

As observed in Figure 1 near half (48%) of studied sample of patients with mental illness express severe level of difficulties in seeking health care services as compared to more than one third (36%) of patients with physical diseases. Meanwhile more than one third (36%) of studied sample of patients with mental illness express moderate level of difficulties in seeking health care services as compared to 60% of patients with physical diseases .

Figure 1: Distribution of barriers among the studied sample (n=100).

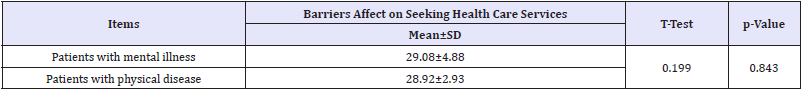

Table 9: Difference between patients with mental illness and patients with physical disease in relation to barriers affecting seeking health care services.

Table 9 revealed that, there is no statistical difference was found between patients with mental illness and patients with physical disease in relation to barriers affecting seeking health care services where t=0.199 at p=0.843.

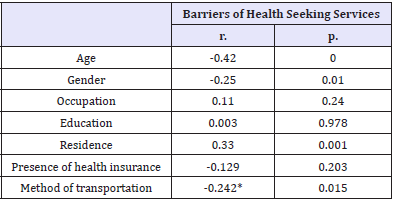

Table 10 reveals that there is a significant correlation between barriers of seeking health care services and age, residence and method of transportation (p=0.000, 0.001, and 0.015) respectively.

Table 10: Relationship between barriers affecting seeking health care services and socio-demographic characteristics of the studied participants (n=100).

*significance at p≤0.05.

Discussion

The result of this study revealed that mean age of both groups (mental and physical patient) were almost similar (34.9 and 32.1), and that makes both samples representing middle age patients which interfere with age extremes which may bias. The results also revealed positive correlation between age and barriers affecting health seeking behaviors. This result can be interpreted that most of the sample were in middle age patients and have physical mental and financial abilities to seek help and services from health care systems. This result is supported by Deeks et al. [10] who revealed that, men and women less than 51 years were more likely to have screening health checks than those more than 50 years.

As regards gender, male mentally ill patients were two thirds of the sample, while physical patients more than half of the sample was male with no statistical difference between the two groups, moreover, there is a positive correlation between gender and barriers affecting health seeking behavior. This result may be due cultural aspects in Egypt that male patients seek mental health care system more than female due to stigma meanwhile; females seek physical health services than male. This results is contradicted by Deeks et al. [10] who revealed that, women were more likely to nominate preparedness to have an annual health check, willingness to seek advice from their medical practitioner and to attend education sessions. Moreover, this result is contradicted with Siegrist et al. [11] who reported that, women reported taking more responsibility for their health, potentially related to risk perception and the gender bias that women are socialized to be more concerned about health issues than men.

Regarding educational level, both groups highest educational levels among patients was can read and write, while the university educational level was the lowest among patients with no statistical difference between the two groups, in addition there is no statistical significance correlation between education and barriers affecting health seeking behavior. This result may be due educational level does not affect health seeking behavior, and that may indicate society awareness about health services is reaching different social categories even different educational levels. This result is contradicted with Zimmerman et al. [12] who stated that, higher level of education is associated with high income which facilitate seeking medical and health services. In another study, lower education level was found to be associated with religious and higher education level with psychiatric help seeking behavior in line with a previous study of Yalvaç et al. [13] which stated that higher education level enables patients to recognize the disease and find beneficial coping styles. We also thought that education enhances knowledge and awareness of disease

Regarding working and occupation among the study groups the current result revealed that there was statistically significant different was found between the two groups, this may be due to nature of psychiatric illness as not working mentally ill patients are higher than physically ill patients. Moreover, there is no statistical correlation was found between occupation and barrier affecting health seeking behavior which may be due equality between working and non-working patients in seeking health care services due to free health services in Egypt. This result is contradicted with Musoke et al. [14] who stated that, the participants’ health seeking behaviour was associated with age.

As regards accessibility of health services including place of residence, availability of transportation, and presence of health insurance among the studied sample the current result showed that there are no association between these factors and health seeking behaviors except for the place of residence and this may be related to health system in Egypt and free paid health care services supports not working patients and those who may have financial difficulties. Moreover, residence distribution was statistically significantly different among both groups, urban mentally ill patients were higher, while rural physically ill patient were higher, that may contributes to the decreased rural areas awareness about mental services seeking behavior, and also that the lack of health services for physically ill patients in rural areas. That is agreed with the reluctance of the general public to seek mental health care is well documented in the literature [15,16].

Factors which have been proposed as contributing to this reluctance among rural impoverished individuals include:

A. Not recognizing symptoms of mental illness,

B. Cost of care,

C. Not knowing where to go,

D. Lack of insurance,

E. Unavailability of providers,

F. Lack of transportation

G. Stigma associated with mental illness, and

H. Worry about unfair treatment.

In spite of experiencing severe level of difficulties in seeking health services by people with mental illnesses as compared to moderate level of difficulties that experienced by those with physical illnesses there is no statistical significance difference between the two groups regarding health seeking behavior. These results may be due presence of mental illness stigma among Egyptian society which may hinder health seeking services by mentally ill patients. These results are agreed with Serra et al. [17] reported that, reasons for seeking non-psychiatric help was mostly due to insufficient knowledge of disease. Inefficacy of drugs and side effects were the other reasons. Sixty nine percent (69%) of patients reported that mental health literacy is a major obstacle to seeking help and receiving effective treatment [18-22].

Conclusion

This current study results concluded that health seeking behavior did not differ in psychotic patients and those with physical illnesses it affected by age, gender, education level, and place of residence [23]. Meanwhile, the level of difficulties of seeking health care services is more severe among those with mental illnesses because of the social stigma about psychiatric illnesses in Egypt [24-27].

Ethical Considerations

A written approval was obtained from the Al-Abassia Mental Health Hospital at the outpatient Clinic, and AL Kaser Al-Ani University Hospital at the Out-patients Clinics to conduct the current study. All subjects were informed that participation in the current study is voluntary, and the data collected will be used only for research purpose, and anonymity and confidentiality of each participant was protected by allocation of a code number for each response. The participants were informed that they can withdraw at any time during the study without giving reasons; confidentiality was assured, and subjects were informed that the content of the tools will be used for the research purposes.

Tools

Data were collected over period of two weeks by using Sociodemographic and medical data sheet, barriers affecting seeking medical services questionnaire.

A. Socio-Demographic Data and medical data Sheet. It was designed by the investigators and it includes personal data, such as age, age on admission, educational level, marital status, occupation, no. of pervious admission for admission.

B. Barriers affecting seeking health care services questionnaire. This questionnaire was developed by the investigators after reviewing the related literature. It was consisted of 20 statements which describe the possible reasons for not seeking health care services among both physically and mentally ill patients. All responses were rated according to the 3 points liker t-scale 0= not applicable, 1=yes, and 2=no.

The total score is the sum of all 20-items, total score ranged from (0 to 40). Total scores were divided as follows:

A. Mild difficulty=<60%

B. Moderate difficulty=60% to less than 75%

C. Severe difficulty=75% and more

The tool was tested by using a test-retest reliability coefficient (0.653).

The investigators translated the instruments (English formats) into Arabic language, rendered the same English formats to bilingual experts for more verification of the translation of the Arabic formats. Then, the resulting versions were translated back into the original language by other bilingual experts who were blind to the original. Minor discrepancies in the content were founded and necessary modifications were done.

Recommendations

Based on the present study findings, the following recommendations are suggested.

A. Introduce orientation programs about mental illnesses and the importance of seeking mental health care services for patients and their families in outpatient clinics.

B. Enhance health seeking behavior in rural areas by increasing the number of mobile clinics in those distant areas.

C. Duplication of the study using a larger sample in different geographical areas to generalize results.

References

- Ember C, Ember M (2004) Cultures cross cultural anthropology. In: Encyclopedia of medical anthropology health and illness in the world’s cultures. Springer Science, New York, USA 1: 3-8.

- Lazarus, Ellen S (1994) What do women want: Issues of choice, control, and class in pregnancy and childbirth. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 8(1): 25-46.

- Martucci S, Gulanick M (2012) Health-seeking behaviors: health promotion; lifestyle management; health education; patient education.

- Sandstrom, Kent L, Lively, Kathryn J, Martin, et al. (2014) Symbols, selves, and social reality: a symbolic interactionalist approach to social psychology and sociology (4th edn), Chapter Oxford University Press, New York, USA, pp. 7-8.

- World Health Organization (2015) Social Determinants of Health, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (2013) Progress on the implementation of the Rio Political Declaration, Switzerland.

- Adhikari D, Rijal DP (2014) Factors affecting health seeking behavior of senior citizens of dharan. Journal of Nobel Medical College 3(1): 50-57.

- Currie D, Wiesenberg S (2003) Promoting women’s health-seeking behavior: research and the empowerment of women. Health Care Women Int 24(10): 880-899.

- Prosser T (2007) Utilization of health and medical services: factors influencing health care seeking behavior and unmet health needs in rural areas of Kenya.

- Deeks A, Lombard C, Michelmore J, Teede H (2009) The effects of gender and age on health related behaviors. BMC Public Health 9: 213.

- Siegrist M, Keller C, Kiers HA (2005) A new look at the psychometric paradigm of perception of hazards. Risk Anal 25(1): 211-222.

- Zimmerman E, Woolf S, Haley A (2014) Population health: behavioral and social science insights: understanding the relationship between education and health. Institute of Medicine, Washington, USA.

- Yalvaç HD, Kotan Z, Nal S (2015) Help seeking behavior and related factors in schizophrenia patients: a comparative study of two populations from eastern and western Turkey. Dusunen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 28: 154-161.

- Musoke D, Boynton P, Ceri B, Musoke M (2014) Health seeking behaviour and challenges in utilising health facilities in Wakiso district, Uganda. Afr Health Sci 14(4): 1046-1055.

- Kessler RC, Olfson M, Berglund PA (1998) Patterns and predictors of treatment contact after first onset of psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry 155(1): 62-69.

- Regier RD, Cortes DE (1993) Help-seeking pathways: A uniform concept in mental health care. Am J Psychiatry 150(4): 554-561.

- Serra M, Lai A, Buizza C, Pioli R, Preti A, et al. (2013) Beliefs and attitudes among Italian high school students toward people with severe mental disorders. J Nerv Ment Dise 201(4): 311-318.

- Al Fayez H, Lappin J, Murray R, Boydell J (2015) Duration of untreated psychosis and pathway to care in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Early Interv Psychiatry 11(1): 47-56.

- Ansari Z, Carson NJ, Ackland MJ, Vaughan L, Serraglio A (2003) A public health model of the social determinants of health. Soz Praventivmed 48(4): 242-251.

- Celik Y, Hotchkiss D (2000) The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in turkey. Soc Sci Med 50(12): 1797- 1806.

- Correa Rotter R, Naicker S, Katz IJ, Agarwal SK, Herrera Valdes R, et al. (2004) Demographic and epidemiologic transition in the developing world: role of albuminuria in the early diagnosis and prevention of renal and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int Suppl 92: S32-S37.

- Currie D, Wiesenberg S (2009) Promoting women’s health-seeking behavior: research and the empowerment of women. Health Care Women Int 24(10): 880-899.

- Gwatkin DR (2000) Health inequalities and the health of the poor: what do we know? What can we do? Bulletin of world health organization 78 (1): 3-18.

- Hunt L (1994) The women’s health movement: one solution. In: Waddell C, Petersen AR (Eds.), Just health. Churchill Livingstone, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 387-395.

- Kapur RL (1979) The role of traditional healers in mental health care in rural India. Social Sciences and Medicine 13B(1): 27-31.

- Naicker T, Khedun S, Moodley J, Pijnenborg R (2003) Quantitative analysis of trophoblast invasion in preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82(8): 722-729.

- Thisted RA (2003) Are there social determinants of health and disease? Perspect Biol Med 46(3): S65-S73.

© 2018 Naglaa M Gaber. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)