- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Physical and Psychological Violence against Married Men in District Dir (Lower), Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa, Pakistan

Hizbullah Khan1, Tazeen Saeed Ali2*, Aamir Abdullah3 and Shadbehr Shahid4

1Director Nursing Services, Hayatabad Medical Complex, Pakistan

2Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, School of Nursing and Midwifery and, Pakistan

3Shaukat Khanam Memorial Hospital and Research Centre, Clinical Nurse Manager, Pakistan

4Aga Khan University, Pakistan

*Corresponding author: Tazeen Saeed Ali, Associate Professor, Assistant Dean, Research and Graduate Studies School of Nursing and Midwifery & Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, PO Box 3500, Karachi, Pakistan, Tel: 00922134865460; Email: tazeen.ali@aku.edu

Submission: February 12, 2017;Published: May 29, 2018

ISSN: 2577-2007 Volume3 Issue2

Introduction

The World Health Organization [1] has defined violence as “the intentional use of physical force, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in, or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal-development or deprivation’’ [1]. According to the WHO [1] typology of violence, there are mainly three types, such as, self-directed, interpersonal, and collective violence; these types are further divided into subtypes [1]. The current study focused on interpersonal (intimate partner or domestic) violence against married men. The Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) can be defined as the physical, psychological, or sexual harm by current/previous partner or spouse; domestic violence is used interchangeably with IPVs [2].

Violence against women is extensively studied in different parts of the western world and Asian countries; however, very few of the researchers have paid attention towards violence against men [3,4]; Hines et al. [5] it is commonly claimed that men are traditionally viewed as being physically stronger than women, therefore, they under-report their victimization due to barriers like embarrassment and masculine ego [6]. The fact that men are victims of IPV, from their female partners, has been identified for the last thirty years [5]; these victims often face the humiliation of being laughed at, accused, belittled, or ridiculed, due to which they do not report their victimization [6]. Studies have identified equal levels of exposure to intimate partner violence among men and women [7]; the rates and frequencies of violence enacted by women are often similar to that of their men partners [8]. Such symmetry signifies a weak association of gender with perpetration of IPV. However, men’s ego has been developed by the society in such a way that their reporting of violence is generally considered a social stigma. When men attempt to report DV against them, most of the times they are not trusted; instead, they are laughed at and ridiculed for the notion that they are beaten by their wives [9].

It is argued that violence is a human issue rather than a gender problem, and violence by women against men should not be ignored [10]. The Domestic Abuse Help Line for Men (DAHM) established in the United States in 2000 received 246 calls in 22months from male callers, in which 77% men themselves called and reported the violence meted out to them by their intimate partners. The rest of the 33% calls were either for their friends or family members. Physically aggressive behavior was frequently reported by 43.7% of the men. In addition, 41.8% of the men reported to have been pushed, 39.2% were kicked, 31% were grabbed, and 24.7% were reported as being punched by their intimate partners. Likewise, a Scottish study also reported the high prevalence of DV against men. This study included 190 interviews of 95 men and 95 women; it revealed that 50.6% of the men and 47.4% of the women reported experiencing of one to four violent events of IPV against themselves in the previous one year [11].

Similarly, a cross sectional study was conducted in Sweden about intimate partner violence (IPV). The investigators collected data from 173 men and 251 women, and concluded that more men (63.9%) than women (39.4%) reported being physically assaulted by their partners in the past one year [12]. A quantitative study was conducted in the United States to identify the help seeking experiences of men who sustain IPV.

The study sample consisted of 302 men, who reported a high magnitude of violence against them from their female partners. The findings of the study revealed that 100% of the women were reported by their men partners as having perpetrated psychological violence, out of which 98.7%, 90.4%, and 54% of women were reported for minor, severe, and very severe physical violence respectively. Contrary to the western studies, very little work has been done in the Asian countries for the identification of DV against men. Save Family Foundation conducted quantitative study about DV against men, which included a sample of 1650 Indian men? The percentages of violence against men by their female partners were reported as: 32.8% economical, 22.2% emotional, 25.2% physical, and 17.7% sexual violence [9]. The above studies show that worldwide DV against men is more prevalent than one would imagine, and, hence, needs to be explored further; so that effective measures can be taken to curb this social ill (Table 1).

Table 1: Participants’ demographics and socio-economic status (n=258).

Factors associated with physical and psychological violence against men

It has been claimed that increasing gender equity can push women to enact violence against their partners [13]. This suggests that when women are empowered more, and their position or authority equals to that of men; they are more likely to initiate DV against their male partners. Besides power dynamics, there are some other factors due to which women enact violence against their partners which are to resolve the arguments, to respond to family crisis, and to stop husband from upsetting the wife. Moreover, a recurrent theme of being ignored and trying to seek attention is reported by many studies as one of the factors due to which women initiate violence against their male partners [14-19]; In addition, low Socio-Economic Status (SES), childhood exposure to violence, and the habit of alcohol abuse can make men more prone to experience IPV [20-23].

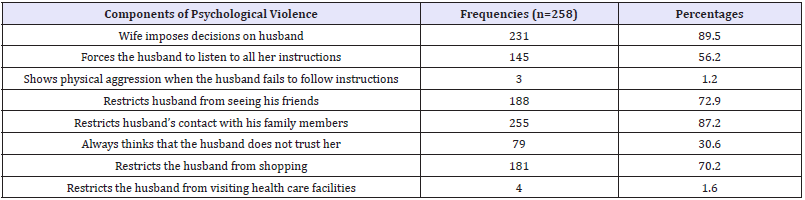

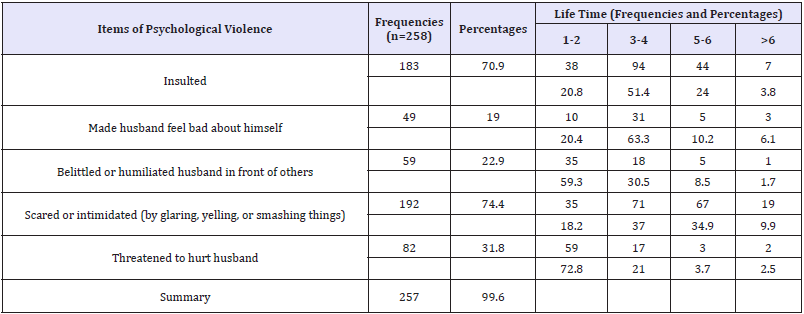

The purpose of this study was to identify the prevalence of DV against married men, and the associated factors of physical, and psychological violence. Furthermore, it aimed to explore the association of health effects with the occurrence of violence (Table 2).

Table 2: Prevalence and frequency of psychological violence over life time (n=258).

Methodology

Study design and setting

A quantitative research approach utilizing the analytical crosssectional study design was employed to answer the research questions. This study was conducted in tehsil Timer garah, which is the headquarter of district Dir (lower), KPK, Pakistan. The target population for this study was all married men currently living with their wives residing in district Dir (lower), KPK. Those who had marital life less than six months were excluded from the study.

Sample size

Table 3

The sample size for the current study was calculated by using the statistical method of EPI Info software 06, on the basis of prevalence and the association of factors with DV against men. A total of 258 participants were included in the current study (Table 3).

Sampling

This study used the purposive sampling technique for the selection of participants. The data was collected from married men who visited the clinic of a general physician and met the inclusion criteria. This is a private clinic located in Timergarah (headquarter of the district), and it is considered as one of the busiest clinics in this area. The reason for choosing a private versus government clinic was the maximum flow of patients and the availability of a separate room for data collection. People usually come to this clinic from most of the areas of the district because of the popularity of the physician.

Study variables

The independent variables considered in this research are: demographic characteristics of the participants, socioeconomic status, level of education, number of children, and family type. The dependent or the outcome variable of the study was domestic violence, which has psychological and physical aspects (Table 4).

Table 4 Prevalence and frequency of physical violence over life time (n=258).

Data collection tool

First of all, a few researchers in the field of DV against men were contacted through e-mail for provision of tool [4], but unfortunately they did not respond. After this, other researchers were contacted for the same purpose and one of them replied and advised the researcher to modify and truncate the WHO [1] Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire” as they had followed the same process for their own study. Finally, “WHO multi-country study on women’s health and life experiences of violence against women” questionnaire [24], was selected and administered to the participants after necessary truncation and modifications.

Validity and reliability of the tool

Table 5 Univariate analysis to identify association between independent variables and physical violence.

Since the WHO [1] tool was truncated and modified, therefore, the content validity and reliability were re-tested. The Content Validity Index of the tool, after the second round, was calculated as 0s.88 for relevance and 0.87 for language clarity. For reliability of the tool, Cronbach alpha was calculated which appeared as 0.63 for psychological, and 0.44 for physical. The study tool in both the languages, i.e., English and Urdu, was pilot tested on 13 married men (5% of the total sample size 258); the data of these participants were not included in the current study (Table 5).

Data collection process

Data collection was started after the formal approval from the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), Karachi, Pakistan. Written permission from the Deputy Commissioner (DC) of the district was taken for conducting this study in the district Dir (lower). Data was collected by the Principal Investigator (PI) and the research assistants. The research assistants were registered nurses who were trained for data collection by the PI and the research supervisor. The study participants were approached as they visited the selected clinic. The purpose of the study was explained to all the participants, and formal written informed consents were taken prior to the data collection (Table 6).

Table 6: Summary and Levels of Severity of Psychological Violence.

Data analysis

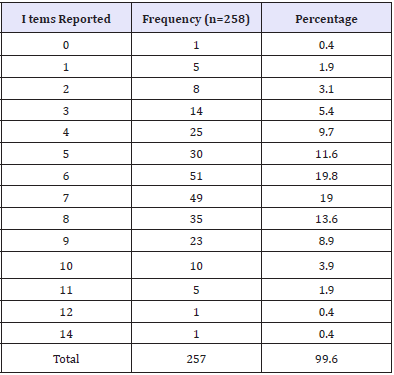

The data were entered in the SPSS version 19 by a data entry programmer and the PI. The entered data were cross checked and errors cleaned by the PI of the study. Descriptive statistics, like frequencies and percentages, were calculated for sociodemographical data, categorical data, and other independent variables. Similarly, frequencies and percentages were calculated for the prevalence of the outcome variables, like psychological and physical violence. The questionnaire included sections about frequency of occurrence of different forms of violence over the last month, last year, and over life time; however, all participants reported their victimization over life time only. Therefore, frequencies and percentages were calculated for a period of life time only. In addition, the health consequences of the participants associated with the occurrence of violence were also calculated in frequencies and percentages. Logistic regression was used as inferential statistics to identify the association among independent variables and outcome variables (Table 7).

Table 7: Level of severity of psychological violence.

Result

Though the questionnaire used in this study was designed to include the frequencies of different forms of violence over the last month, the last 12 months, and over life time, no one reported the occurrence in the last month or last 12 months; hence, only the frequencies of DV over life time are given (Table 8).

Table 8: Summary and Levels of Severity of Physical Violence.

Summary of Physical Violence.

Response rate

Figure 1: Response rate of the participants during data collections.

In the current study, a total of 520 married men were approached one by one according to the inclusion criteria. Among them, 360 men agreed to participate in this study, however, 102 men expressed their wish to discontinue the data collection, and they left during the interview. Finally, data were collected from 258 men successfully, and further data collection was stopped, because this was the estimated sample size for the current study (Figure 1). So, the response rate in the current study was calculated as 258/360 or 71.66%.

Participants’ demographics and socio-economic status

All the participants were in the age range of 22-62 years. A majority (60.07%) fell in the 32-41 years age bracket; 23.64% were aged more than 41 years; followed by 16.28% in the 22-31 years age bracket. The data revealed that a significant majority (96.5%) of the participants could read and write. Among these 96.5%, only 26.4% were highly educated (graduates &masters); 11.6% had studied up to 12 grades; while a majority (62%) had received primary, middle, or matric level of education (Table 1).

Among the participating men, almost all (97.3%) were earning. Most of the men were employed in regular jobs (35.7%), while 28.2% were involved in selling and trading, 15.5% reported seasonal or labor work, and 14.7% were drivers by occupation. Along with earning and occupation, the participants were asked about property in their own name. A majority responded that they had household items (93.8%), large animals (79.1%), small animals (72.1%), house (86%), and land (36.4%). Very few of them owned a car (12%) or bank savings (11.6%) in their own name (Table 1).

The duration for which the couples had been married to each other ranged from 1 to 40 years. The range was further divided into three categories: 44.6% fell in the first category, i.e., 1-10 years; 41.1% fell in the 11-20 years category; followed by 14.3% in the more than 20 years category. A majority of the participants, i.e., 96.5%, reported their marriage as the first marriage, while only 3.5% said that it was their second marriage. The reasons stated for the second marriage were death of spouse (n=6), separation (n=2), and infertility (n=1). When the participants were asked about the number of children they had, 64.6% reported having one to four children, while 35.4% had more than four children. The participants were also inquired about the number of male and female children; 64.7% reported that they had one to two male children, followed by 26% who reported having three to six male children. Similarly, 55.1% stated 1-2 female children, while 27.3% reported having three to six female children (Table 1).

The data revealed that most of the participants (60.1%) were living in extended families, while 39.9% reported that they lived in nuclear families. Regarding the number of family members in the household, 53.9% said that they had eight to twelve family members living together; followed by one to seven members (32.9%), and 13-30 members (13.2%). However, almost two thirds of the participants (72.5%) reported having one to two earning members in their families, while 27.5% said that they had more than two earning members. About the socio-economic status, almost half of all the study participants were either in the lower class or lower middle class according to their monthly household income from all sources. Only 17.4% had a high socio-economic status, followed by 26% who belonged to the upper middle class.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants’ wives

The current study also examined the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants’ wives. Age was investigated in four categories, in which the lowest age was 20 and highest was 60 years. Exactly half (50.0%) of all the wives were between 30-40 years of age, followed by 39.1% who were in the 20-30 years age group, and only 10.9% were in the 40-60 years age bracket. Less than half, (46.1%) of the wives were reported as being able to read and write; among these 46.1%, only 20.8% had achieved higher education (graduation and masters).Regarding employment status, the majority of women (84.5%) were housewives, 14.7% were reported as working women, and only 0.8% were still students. Of the working women, 9.0% belonged to the teaching profession, and 5.9% were employed in other professional jobs.

The study participants were also asked about their wives’ family background, to determine whether they were better off in any respect. In this regard, 29.5% of the respondents shared that both the families were equal; however, 33.3% shared that they were financially stronger, 29.1% said that their wives’ families had more male members, and 8.1% reported that they had political affiliations and, hence, were more influential.

Psychological violence

Among all forms of violence, the participants openly reported their exposure to some kind of psychological abuse by their female partners (Table 2). An obvious majority (n=258, 89.5%) said that their wives imposed some or other form of decisions on them. Similarly, 56.2% reported that their wives verbally forced them to listen to all their instructions; however; only 1.2% reported facing physical aggression from their partners if their instructions were not followed. In addition, imposing restrictions with regard to contacting family members, seeing friends, and shopping, were reported by 87.2%, 72.9%, 70.2%, respectively. Among all the participants, 30.6% stated that their wives always felt that they were not trusted. The summary percentages were calculated for psychological violence to measure its prevalence. Almost all the participants (n=257, 99.6%) reported that they had been exposed to some kind of psychological abuse over their life time. Among the exposed, 32.2% faced mild (≤ 5 items), and 19.7% faced moderate psychological violence (≤ 6 items). Similarly, 32.6% were categorized as those who were subjected to severe (faced ≤ 8 items), and 15.5% to very severe psychological violence (faced ≥ 9 items).

Physical violence

Table 3 explains the frequencies and percentages of physical violence over the entire marital life. With respect to all the components of this section, very few men, i.e., seven and one, reported being slapped or kicked respectively. A majority of the men 158 (61.2%) reported that they were pushed by their wives, most of them (65) reported three to four times, and 56 reported five to six times exposure to such behavior over their entire marital life. Similarly, 18 men reported that they were pulled by their hair; only two of them confirmed their exposure to such type of physical violence for five to six times, and three for three to four times over their life time. Furthermore, a significant number of men (n=104, 40.3%) reported that some object that could hurt was hurled at them. A similar component “being hit with something else” was reported by 19 men, among whom, only two reported being hit for five to six times over their life time. In addition, a considerable number (n=45, 17.4%) reported that they were punched by their wives. Among the exposed men, only one reported being punched more than six times, and three men reported that this happened to them five to six times over their life time. Besides, this study also revealed that 14 (5.4%) women tried to burn/scald their husbands with something hot; seven women made use of hot food stuff, four used hot iron, and three used hot water (Table 9).

Table 9: Level of Severity of Physical Violence.

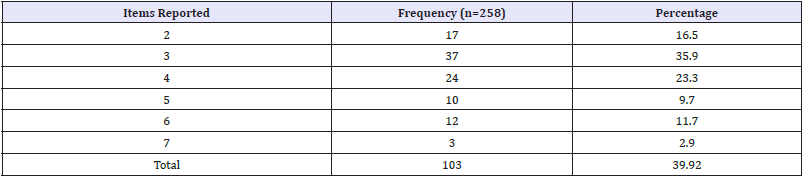

The percentages summary calculated to identify the prevalence of physical violence among the study subjects revealed that 103 (39.42%) men were exposed to some kind of physical violence over their marital life time. The data revealed that 17 of all the exposed men faced mild (faced≤2items), while 37 faced moderate physical violence (faced≤3items). Similarly, 24 were categorized as those who were subjected to severe (faced≤4items), and 25 to very severe physical violence (faced≥5items).

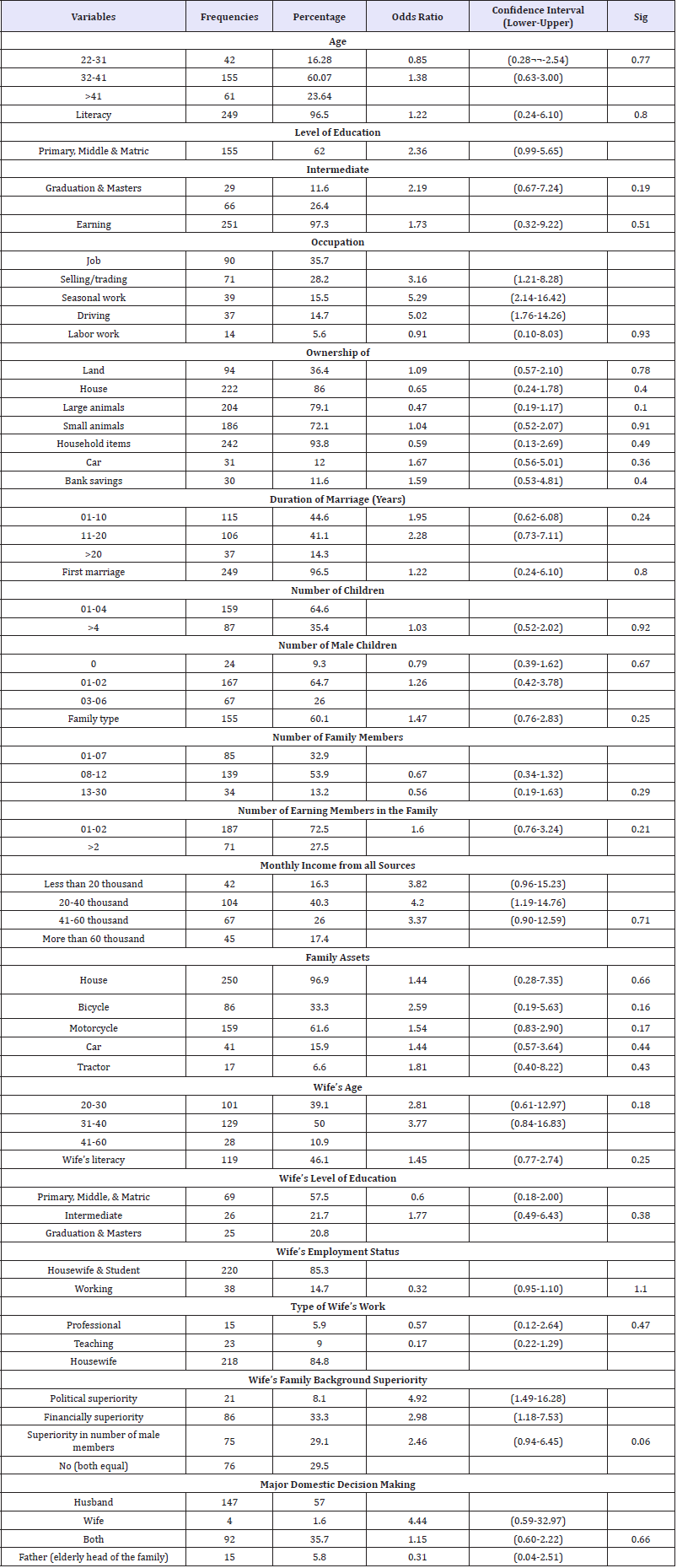

Associated factors of physical and psychological violence

The second question of the current study was to identify the associated factors of physical and psychological violence against married men. Since the prevalence of psychological and physical violence was very high, i.e., 99.6% and 89.14%, respectively, it was therefore decided to find out the association of independent variables and the occurrence of physical violence only? This section shares the results of the univariate analysis that was done between the socio-demographic variables and the occurrence of physical violence over life time. All the independent variables were individually run with the outcome variable (physical violence) in logistic regression, at 95% confidence interval (Table 4). However, none of the variables was found to be significant in the current study, therefore, the researcher decided to skip the multivariate analysis of insignificant variables.

Discussion

Prevalence of psychological and physical violence

In the current study, overall exposure to psychological violence was reported by almost all the participants which is very similar to the findings of a study conducted in the US, which identified that 100% (n=302) of the men were subjected to psychological violence by their wives [25]. However, the overall prevalence of psychological violence identified by the current study is considerably high if compared with some other studies. A Chinese study identified that around 50% of the participants had been exposed to psychological violence [26], whereas an Indian study showed 40%its participants and a Swedish study found that almost 10% had to face it [27]. One reason for such varied rates could be the type of study tools utilized for data collection for the identification of psychological violence.

Some items which were frequently reported by the participants in this study were ‘restriction from seeing friends’ by 72.9%, ‘being insulted’ buy 70.9%, ‘intimidated by glaring, yelling, smashing things’ by 74.4%, and ‘threatened to hurt’ by 31.8%. Comparatively, a study conducted in the US showed higher rates (except restriction from seeing friends, which was 68.2%)like ‘being insulted’ was reported by 99%, ‘intimidated by glaring, yelling, smashing things’ by 99.3%, and ‘threatened to hurt’ by 75.5%. In the present study, the overall identified prevalence of physical abuse was 39.92%. The results showed that 16.5% of the participants had been exposed to mild, 35.9% to moderate, 23.3% to severe, and 24.3% to very severe physical abuse. This finding of overall prevalence is relatively high in comparison with the results of an Indian study, which identified 25.2% physical abuse [9]. Comparatively, a Chinese study reported 10.5% [28], and a Swedish study reported 11% physical abuse [12].

However, a study on IPV in the US reported very high rates and severity of physical abuse. It was reported that 80% of the male partners were exposed to physical abuse, and 40% of them had exposure to very severe physical abuse [5,8]. The most frequently reported items for physical abuse in the current study were being pushed (61.2%), hit by something that was thrown (40.3%), and hit with fist (17.4%). The other items which were reported very infrequently included slapped (2.7%), pulled hair (7.0%), and kicked (0.4%). Similar items were reported with higher rates by studies conducted in the US. The findings of one study reported such items as pushed (41.8%), punched (24.7%), slapped/hit (43%), and kicked (39.2%) [8]; in comparison with the current study findings, except for the item “pushed”, these are very high rates. Similarly, another US study identified significantly high rates for the above items, where pushed was reported by 93%, thrown something that could hurt by 82.5%, slapped by 71.9%, punched or hit with something else that could hurt by 84.5%, and kicked by 56.3%.

Associated factors of physical and psychological violence

In the current study, the overall prevalence identified for psychological and sexual violence was very high, i.e., 99.6% and 89.14%, respectively, therefore association was sought for physical violence only. A similar process was carried out in one of the studies, where logistic regression for such maximum rates was not performed [5,8]. A univariate analysis, at 95% confidence interval, was carried out for all the independent variables with physical violence, one by one. Yet, all the independent variables remained statistically insignificant in the current study. Despite of this our study shows slight significance when it comes to wife’s family background which highlights that if she is politically and/ or financially superior, so their husbands are more likely to be the victim of physical and psychological violence.

Various associated factors have been identified as significant in some previous studies. An Indian study reported a direct association between duration of marriage and the probability of violence. Similarly, another study identified that the length of relationship and the age of the participants played a significant role in DV, according to which, younger aged participants were more vulnerable to both perpetration and victimization of DV. Lower levels of education and unemployment were also found significant in some studies. In addition, low income and the habit of alcohol abuse have also been identified as potential risk factors for DV victimization [20].

Strengths

The major strength of the current study is that, as for as the researcher knows, it is the first study in Pakistan which investigated the phenomenon of DV against men, and it could serve as the foundation for further researches on DV in the country. It identified the prevalence of psychological, physical, and of DV, and attempted to investigate its associated factors, in addition to exploring health consequences faced as a result of DV. The current study gathered rich information on the phenomenon in a challenging and conservative population where the patriarchy is highly prevalent.

Limitations

There are some limitations of the current study. Most importantly, the data was collected from a physician’s clinic, due to which the findings cannot be generalized to the general population. Secondly, the participants in the current study did not report about their past 12 months’ exposure to any kind of violence; they only reported their life time frequencies of occurrence. Since, the duration of marriage in the current study ranged from one to thirty years, it is possible that the frequencies of occurrence might not have been reported accurately due to recall bias. Another limitation of the current study is that, the Cronbach alpha values are less than the acceptable range, because the WHO [1] tool for research on women was used for the first time in a study on men in the Pakistani context. Lastly, due to time and budget limitations, a small sample size was taken to conveniently conduct the current study.

Recommendations

This study sets forth some recommendations on different levels in order to address the issue of against men which has deleterious health consequences. The public health personnel, physicians and nurses, should include a few questions regarding DV in their routine history taking. If a patient reports his victimization, he should be thoroughly investigated. Government should arrange DV telephonic help lines for men in each district so that they could report their exposure in details. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the media should also devise different strategies for the promotion of family harmony and reduction of general domestic conflicts

Research

A qualitative study is recommended on DV against men in order to get an in depth understanding of the phenomenon. There is one assumption about the violence perpetrating women that they merely use violence against their partners in self-defense [28-33]. It is, therefore, recommended that a population based study, including equal number of men and women be conducted in the community setting in order to identify the true picture of DV against men in Pakistan.

Conclusion

DV against men exists throughout the world in both developed and developing countries. The current study identified tremendously high rates of all forms of DV in District Dir (lower). Psychological violence was found to be the most prevalent form of DV, followed by sexual and physical violence. None of the sociodemographic variables in the current study was found to be statistically significant. Several health effects that were identified as a result of different forms of DV against men include initiation of substance abuse; feelings of anger, shame, fear, and difficulty in sleeping; suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempt. The government of Pakistan, public health personnel, and NGOs should take initiatives collaboratively and introduce and implement prompt interventions to reduce the severity of the issue.

References

- WHO (2002) World report on violence and health: Summary.

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB (2002) The world report on violence and health. Lancet 360(9339): 1083-1088.

- Rutherford A, Zwi AB, Grove NJ, Butchart A (2007) Violence: a glossary. J Epidemiol Community Health 61(8): 676-680.

- Corry CE, Fiebert MS, Pizzey E (2002) Controlling domestic violence against men. pp. 1-17.

- Douglas EM, Hines DA (2011) The help seeking experiences of men who sustain intimate partner violence: An overlooked population and implications for practice. J Fam Violence 26(6): 473-485.

- Du Plat Jones J (2006) Domestic violence: the role of health professionals. Nurs Stand 21(14-16): 44-48.

- Heiskanen M, Ruuskanen E (2011) Men’s experiences of violence in Finland 2009. European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI), USA, pp. 1-105.

- Belknap J, Melton H (2005) Are heterosexual men also victims of intimate partner abuse? In Applied Research Forum, National Electronic Network on Violence against Women. pp. 1-12.

- Cook PW (2009) Abused men: The hidden side of domestic violence. (2nd edn), Praeger, Westport, USA.

- Dixon L, Graham-Kevan N (2011) Understanding the nature and etiology of intimate partner violence and implications for practice and policy. Clin Psychol Rev 31(7): 1145-1155.

- Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, Sullivan TP, Snow DL (2008) A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence Vict 23(3): 301-314.

- Sarkar S, Dsouza R, Dasgupta A (2007) Domestic violence against men-a study report by Save Family Foundation. New Delhi, India.

- Hines DA, Brown J, Dunning E (2007) Characteristics of callers to the domestic abuse helpline for men. J Fam Violence 22(2): 63-72.

- Dobash RP, Dobash RE (2004) Women’s violence to men in intimate relationships working on a puzzle. British Journal of Criminology 44(3): 324-349.

- Lovestad S, Krantz G (2012) Men’s and women’s exposure and perpetration of partner violence: an epidemiological study from Sweden. Biomedical Central of Public Health 12(1): 945.

- Goicolea I, Ohman A, Torres MS, Morras I, Edin K (2012) Condemning violence without rejecting sexism? Exploring how young men understand intimate partner violence in Ecuador. Glob Health Action 5.

- O’leary SG, Slep AMS (2006) Precipitants of partner aggression. J Fam Psychol 20(2): 344-347.

- Olson LN, Lloyd SA (2005) It depends on what you mean by starting: An exploration of how women define initiation of aggression and their motives for behaving aggressively. Sex Roles 53(7-8): 603-617.

- Rosen KH, Stith ESM, Few AL, Daly KL, Tritt DR (2005) A qualitative investigation of Johnson’s typology. Violence Vict 20(3): 319-334.

- Seamans CL, Rubin LJ, Stabb SD (2007) Women domestic violence offenders: Lessons of violence and survival. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 8(2): 47-68.

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Hellmuth JC, Ramsey SE, Kahler CW (2006) Reasons for intimate partner violence perpetration among arrested women. Violence Against Women 12(7): 609-621.

- Weston R, Marshall LL, Coker AL (2007) Women’s motives for violent and nonviolent behaviors in conflicts. J Interpers Violence 22(8): 1043- 1065.

- Caetano R, Vaeth PAC, Ramisetty-Mikler S (2008) Intimate partner violence victim and perpetrator characteristics among couples in the United States. J Fam Violence 23(6): 507-518.

- Smith SAM, Foran HM, Heyman RE, Snarr JD (2011) Risk factors for clinically significant intimate partner violence among active‐duty members. Journal of Marriage and Family 73(2): 486-501.

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S (2011) Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. J Interpers Violence 26(14): 2764-2789.

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK (2012) A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 3(2): 231-280.

- Mary E, Lori H (2005) Researching Violence against women: A practical guide for researchers and advisers. WHO 1-28.

- Chan KL (2012) Gender Symmetry in the Self-Reporting of Intimate Partner Violence. J Interpers Violence 27(2): 263-286.

- Hines D, Douglas E (2010) Intimate terrorism by women towards men: does it exist? J Aggress Confl Peace Res 2(3): 36-56.

- Nybergh L, Taft C, Enander V, Krantz G (2013) Self-reported exposure to intimate partner violence among women and men in Sweden: results from a population-based survey. BMC Public Health 13(1): 845.

- Denise AH, Jan B, Edward D (2007) Characteristics of callers to the domestic abuse helpline for men. J Fam Viol 22: 63-72.

- Lanier C, Maume MO (2009) Intimate partner violence and social isolation across the rural/urban divide. Violence against Women 15(11): 1311-1330.

- Loseke DR, Kurz D (2005) Men’s violence toward women is the serious social problem. Current Controversies on Family Violence 2: 79-96.

© 2018 Tazeen Saeed Ali. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)