- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

An Assessment of Eighth Grade Students’ Health Promotion Behaviours

Rabia Sohbet1, Fatma Gecici2, Canan Birimoglu Okuyan3*

1Assistant Professor, Gaziantep University, Turkey

2Lecturer, Hasan Kalyoncu University, Gaziantep, Turkey

3Post Doctoral Researcher, Mustafa Kemal University, Hatay Health College, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Canan BİRİMOĞLU OKUYAN, Post Doctoral Research Assistant, Hatay Health School, Mustafa Kemal University, Antakya, Turkey, Tel: +903262160686; Email: cananbirimoglu@gmail.com

Submission: April 06, 2018;Published: May 11, 2018

ISSN: 2577-2007 Volume2 Issue4

Abstract

This study aims to assess the health promotion behavior of eighth grade students. The population of this research includes 2791 students who were eighth grade in Primary School, Gaziantep. The research aimed to reach the entire population, yet ended with 2476 students. Mean age average of the adolescents involved in the study was 14.00±0.57, and their overall AHPS score was 139.21±25.12. Assessed by sex, female students scored meaningfully higher than the male students (p<.05). The children, whose parents are high school graduates or higher, performed better than the other parents’ children. Moreover, monthly income also predicted the students’ scores. Adolescents’ AHPS scores are not at the desired level. Findings show that school health nurses should organize training programs that also include the families and school staff. This program should be based on sociodemographic data and cover nutrition, exercise, stress management, and health responsibility.

Keywords: Adolescent; Health promoting; Behaviours; Nursing

Introduction

Health behavior is known as the total sum of the knowledge, belief, application and approaches oriented to improve and sustain health [1]. Health promotion aims to increase individuals’ control over their health, which will result in a decrease in risk of diseases and an increase in life expectancy, the quality of all health services and overall life quality [2]. The correct health behavior of individuals will help improve their health while wrongdoings will lead to diseases. Therefore, acquisition of the right health behavior in early years of life will improve overall life quality by reducing the risk of suffering from diseases [3,4]. Ahealthy life style usually starts at childhood, carried over to adolescence [5]. World Health Organization defines adolescence as the period between 10 and 19 years of age. Puberty is the phase of life when an individual develops and matures in biological, psychological, physical and social terms. It is also a formidable phase when problems may arise for both adolescents and their family members [6]. One can say that the prospective health profile of the adolescents depends on how they go through puberty. Many people acquire some set of behaviours during puberty that poses risks to their health [4,7].

Center for Disease Control and Prevention states that these behaviors may include addiction to cigarettes, alcohol and other substances, sexual actions, malnutrition, insufficient physical activity, and behaviors that might result in injuries and violence [8]. Dil et al. [9] reported that among the adolescents studied, 33.7% smoke, 1.3% drink alcohol, 0.2% use cannabis, 37% drive without a license and 59.3% drive without seatbelt on. In another study Metinoğlu et al. [10] found that obesity is a serious health risk that affects 25-30% of children and adolescents [10]. Furthermore, Aksoydan & Çakır [11] found that 79% of adolescents do not perform sufficient physical activity and 14.7% are overweight while 4.1% are obese [11,12]. A study that evaluates the nursery training to fight cigarette addiction of adolescents in Ankara, Turkey reveals that student and peer training helps them quit smoking by informing them about the risks that smoking poses [13]. Adolescents gather in school and we can take advantage of it to offer them an effective school health program and help them (avoid or abstain) risky behaviors [14,15]. Adolescents who are under a certain amount of risk since they don’t attend school should be provided with health service by health centers and observed regularly [16]. Since we want them to be the healthy individuals of the future, we should teach them health-improving behavior while they are still young. Finding out the risky behaviors that threaten adolescents and conducting studies on health-improving practices will greatly benefit adolescent health [17].

Method

The population of this cross-sectional descriptive study includes 2791 students who were eighth grade in Sehitkamil Primary School, Gaziantep (13 schools in total) during 2012-2013 academic year. Although we intended to reach the entire population, the study was concluded with 2476 students, 1280 female and 1196 male. The data sheet comprises two sections, which are aligned with the relevant literature [2-4,7,9]. The first section is allocated to 16 questions that assess the adolescents’ socio-demographic profiles and their risky behaviors. The second section is the Adolescent Health Promotion Scale (AHPS). AHPS was developed by Chen et al. [16] and it is used to assess adolescent health behavior promotion level. Bayık Temel et al. [18] tested the reliability of the scale in Turkey, concluding that it is a valid and reliable scale for Turkish society.

AHPS has 40 items and 6 subfields. The subscales are selfrealization (8 items) health responsibility (8 items), exercise (5 items), social support (7 items), stress management (6 items), nutrition (6 items). These are assessed by a Likert-type scale with different levels from 1 to 5. The minimum score is 40 while the maximum possible score is 200. Any value below the average of the scores from the overall scale was considered as low score while any value above the overall scale was considered as high score. Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.93 for the whole scale, varying between 0.50 and 0.86 for the subscales [16,18]. For this study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was calculated as 0.90 for the whole scale and 0.67-0.78 for the subscales.

Before any data was collected, the students were instructed in how to fill in the forms and they were informed of the purpose of the study. The test was conducted for 15 to 20 minutes. The data was processed using SPSS software (Statistical packet for Social Sciences for Windows). Independent-Samples t-test and oneway ANOVA were used to compare the differences between the groups, and post -hoc Tukey HDS was used to find the origin of the difference. P value was set to 0.05 for all analyses as a measure of significance (Alternative: For all analyses, p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant).

Result

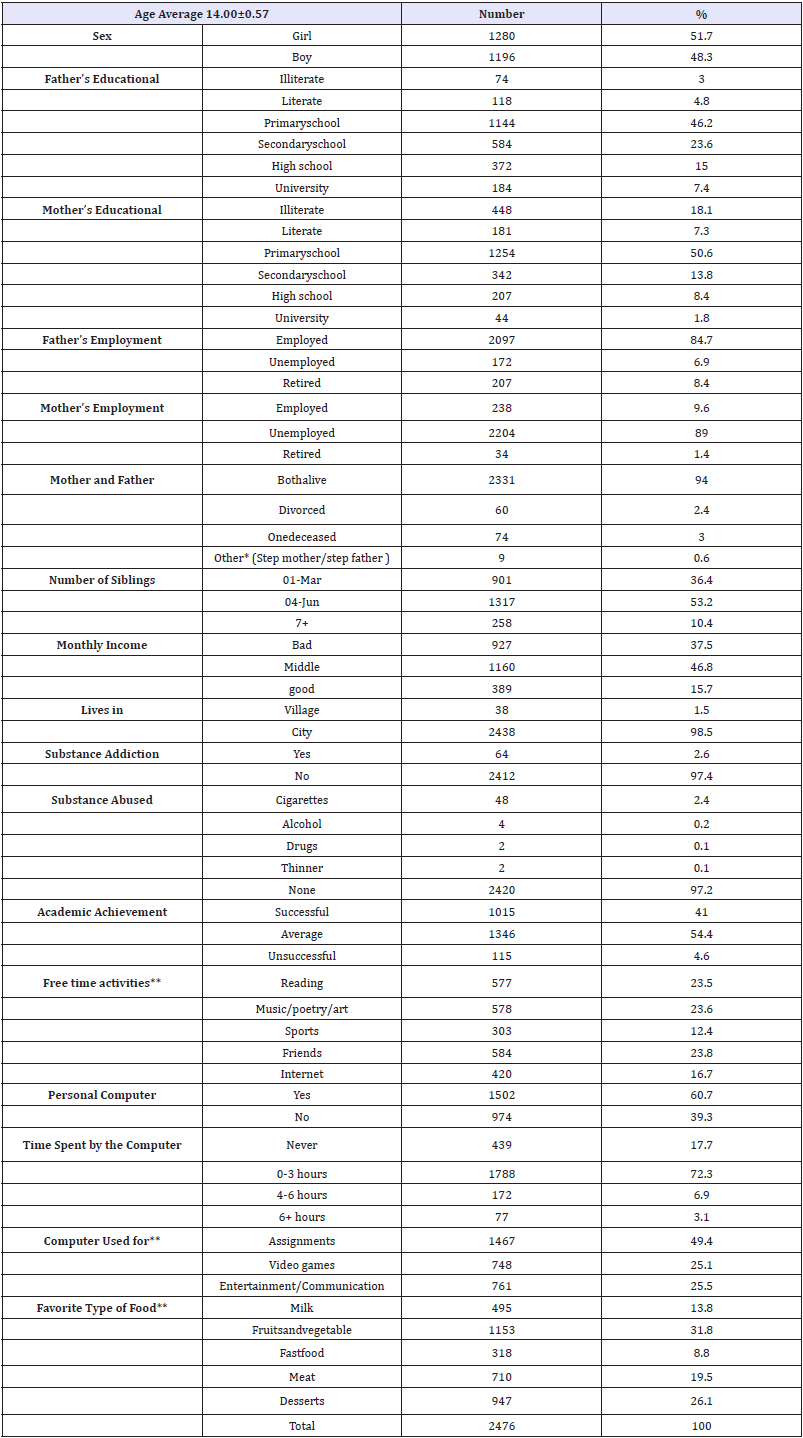

The age average of the subjects is 14.00±0.57 (min: 12, max: 17); 51.7% of them are girls. 46.2% of the fathers are primary school graduates; 50.6% of the mothers are primary school graduates and 18.1% of them are illiterate. 53.2% of the adolescents involved in the study had 4 to 6 siblings; 46.8 of them are from middle income families; 98.5% live an urban life and 54.4% claim an average academic achievement at school. 23.8% of the subjects declare that they spend their free times with their friends; 23.6% engage with music, poetry and art; 23.5% read books; 16.7% spend time on the internet and 12.4% do sports. 60.7% have a personal computer; 72.3% spend 0-3 hours by computer; 49.4% do research for school assignments; 25.5% use their computer for fun and communication while 25.1% use their computer for video games. 31.8% eat fruit and vegetable; 26.1% eat sweets, 19.5% eat beef; 13.8% drink milk; 8.8% eat fast food for their main source of nutrition (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic distribution of the Profiles of the Adolescents involved.

*Stepfather or stepmother, both deceased.

**More than one choice was marked.

The data indicates that the girls (141.37±23.54) scored significantly higher than the boys (136.90±26.52) in overall scores (tests) (p<.05). Furthermore, they performed considerably better in the self-realization, health responsibility, social support and stress management subscales. On the other hand, the boys performed better in the exercise and nutrition subscales (Table 2).

Table 2: Students’ score in AHPS.

AHPS: Adolescent Health Development Scale.

Table 3 illustrates that the students aged 12 and 13 performed significantly better (140.53±26.11) than the other age groups (p<.05). Tukey HSD suggests that this is due to the students aged 16 and 17. The students aged 14-15 performed significantly better in self-realization subscale than the rest of the population while 12- 13 had a similar superior performance in social support and stress management (Table 3).

Regarding the number of siblings, the students who had 1-3 siblings achieved significantly higher scores (140.65±26.11) than the rest of the population (p<.05). Tukey HSD indicates that this is due to the students who had 7 or more siblings. Also, the students who had 1-3 siblings performed meaningfully better than the rest of the population in self-realization, social support and stress management subscales. The students who had 4-6 sibling performed better in the exercise subscale. The students living in the city achieved higher scores (139.42±25.02) than the students living in the country (125.65±26.87, p<.05). Similarly, they performed significantly better in the self-realization, health responsibility, social support, stress management and nutrition subscales (Table 3).

The students with higher academic achievement got higher scores in the overall scale (146.84±23.84), and the difference is meaningful (p<.05). Furthermore, they had meaningfully higher scores in the self-realization, health responsibility, exercise, social support, stress management and nutrition subscales (Table 3). Nonabusers got higher scores (139.54±24.99) than substance abusers (126.75±27.07) with a meaningful difference (p<.05). Non-abusers also outperformed the abusers in the self-realization, health responsibility, exercise, social support and stress management subscales.

The children, whose mothers were in high school graduated and higher, ranked higher (144.13±23.03) than the children of mothers who were middle school graduates and lower (138.66±25.29). The difference is meaningful (p<.05). These subjects also performed considerably better than the others in the self-realization, social support and stress management subscales with a meaningful difference (p<.05) (Table 3).

The children of fathers educated to high school and higher ranked higher (142.84±23.43) than the children of fathers educated to middle school and lower (138.16±25.50) The difference is meaningful (p<.05). These subjects also surpassed the others in the self-realization, health responsibility, social support, stress management and nutrition subscales with a meaningful difference (p<.05) (Table 3). The children of retired fathers were more successful (141.00±24.61) than the children of other fathers. The difference seems to be significant (p<.05). Tukey HSD shows that it stems from the children of unemployed fathers. The children of wealthy families scored better (143.83±25.33) than the children of disadvantaged families. The difference is meaningful (p<.05). Tukey HSD assessment suggests that this difference is linked to the middle class families. Children of wealthy families scored statistically better than the rest of the population in self-realization, social support and stress management sub-scales (p<.05) (Table 3).

Table 3: The Comparison of the Adolescents’ Total AHPS Scores and Subscale Scores Based on their profiles.

Discussion

Adolescence is a phase of life when an individual needs to maintain a sufficient and balanced diet, exercise regularly, undertake the responsibility of their health, achieve self-realization, mature by developing their social networks and be able to manage stress. Health promotion is associated with the individual’s sociodemographic profile. The attention that adolescents pay to these aspects of life and their positive attitude towards them will promote their health. This paper aims to assess the health promoting behaviors of children who are eighth grade students.

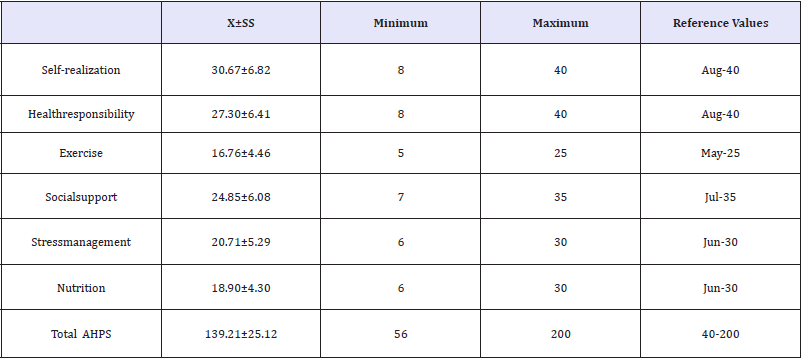

The overall average AHPS score of all adolescents involved in the study was found to be 139.21±25.12. The minimum possible score on scale is 40 while the maximum is 200. The highest average scores were achieved in the self-realization and health responsibility sub-scales (Table 2). This is similar to the study of Karadamar et al. [19] in which they found that high school students living in Adana scored highest in these subscales [19]. The children of employed fathers performed better in the self-realization subscale while the children of retired fathers performed better in the social support and stress management. Health responsibility is an individual’s taking part in the protection of their physical, psychological and social well-being. An individual’s promoting, protective and preemptive behavior towards their health depends on their sex, level of education, income, academic success, nutritional habits and cultural values [20]. The findings of this study reveal that adolescents in Turkey perform better in self-realization than other health promoting behaviors, and this should be further advanced. In addition, if we are to reduce the cost of diseases in the country, along with the number of cases, attention must be paid to enhance the adolescents’ personal health responsibility.

The exercise and nutrition sub-scales were the parts of AHPS where the subjects performed poorly (Table 2). This finding of ours is in parallel with other studies conducted in Şanlıurfa, Adana and Malatya by Dağdeviren & Şimşek [4], Karadamar et al. [19] and Geçkil & Yıldız [3] It is known that regular exercise balances blood pressure, increases lung capacity, enhances lipid fat metabolism, helps with self-confidence, which is necessary to deal with the problems during puberty, supports inter-personal relations and reduces the frequency of depressions. In today’s world, most adolescents live on a fast food diet that is rich in fat and salt. Their consumption of fruits and vegetable is minimal. Turan et al. [21] concluded that eating habits of all students can be classified as risky [21].

It is seen in the present study that girls achieved meaningfully higher overall scores in AHPS than boys. However, the boys surpassed the girls in exercise and nutrition sub-scales (Table 3). This is in parallel with the literature where boys outperform girls in exercise and nutrition sub-scales [2,3,9]. It points out the fact that girls are under higher risks than boys with respect to exercising habits. One can say that social gender may have positive or negative effects on exercise and nutrition. Conditioned by their social role, girls spend more time at home than boys. The difference is more clearly pronounced in adolescence. Staying at home most of their times, girls are exposed to the beauty criteria presented by the media. Yet they don’t have the opportunity to exercise, which leads them to specific diets [3,16].

The data suggests that there is a reverse correlation between age and health promotion scores (Table 3). There are similar studies in the literature that achieved the same conclusion [2,14]. This could be due to the fact that as adolescents grow older they feel more stress about the university entrance exams in Turkey. In addition to this, parents become more tolerant towards adolescents as they grow older, which results in less control. Therefore, they are vulnerable to any adverse effects on their health. We also found that adolescents who have more siblings than the others scored less than the others (Table 3). Studies can be found in the literature that have similar results [9,19]. One possible reason of this finding can be high number of children in a family which restricts the family’s ability to offer economic and social care for the children. Academic achievement, on the other hand, seems to be correlated with health promoting behaviors. That is, relatively less successful students achieved lower scores in AHPS (Table 3). Highly successful adolescents have positive health promoting behaviors [22]. Reducing academic achievement may lead to health-threatening behaviors.

There is a meaningful correlation between the health promoting behaviors of adolescents and their parents’ levels of education (Table 3). The literature concurs that the children of educated parents score better than the children of uneducated parents [2,4,9]. Parents, who naturally greatly affect the adolescent development, can help them acquire health-promoting behaviors. Highly educated parents can have access to health related knowledge and pass it to their children. More importantly, they are the role models who encourage their children to acquire healthpromoting behaviors. Family income also predicts the students’ AHPS scores. The students from high earning families scored better in the self-realization, social support and stress management subscales (Table 3). Sevil et al. [14] reported that high-income family members performed better in the health responsibility and stress management subscales in addition their higher scores in the overall test [14]. This is in parallel with similar studies in the literature about this subject [6,9,23]. Economic factors seem to have an effect on such health-promoting behaviors as interpersonal support, health responsibility, self-realization, nutrition, and exercise.

Conclusion

Adolescents’ AHPS scores are not at the desired level. There seems to be positive correlation between their AHPS scores and sex, age, number of siblings, academic success, parents’ level of education, paternal job status, level of income, and the place where they live (rural vs. urban). Girls achieved higher overall AHPS scores. Age and number of siblings are inversely correlated with AHPS scores while academic success and parents’ level of education are positively correlated. The score averages of the subscales are as follows from high to low: self-realization, health responsibility, social support, stress management, nutrition, and exercise. We can conclude that school health nurses should organize training programs that also include the families and school staff. This program should be based on socio-demographic data and cover nutrition, exercise, stress management, and health responsibility.

References

- Geckil E, Yıldız S (2006) The effect of nutrition and coping with stress education on adolescents’ health promotion. Journal of Cumhuriyet University Nursing High School 10: 19-28.

- Bebis H, Akpunar D, Özdemir S, Kılıc S (2015) Assessment of health promotion behavior of adolescents in a high school. Gülhane Medical Journal 57: 129-135.

- Geckil E, Yıldız S (2006) Adolescent health behaviours and problems. Journal of Hacettepe University School of Nursing 13: 26-34.

- Dagdeviren Z, Simsek Z (2013) Health promotion behaviours and related factors of high school students in Sanlıurfa. TAF Preventive Medicine Bulletin 12(2): 135-142.

- Wong DL, Hocken berry MJ (2003) Nursingcare of Infants and children, St Louis, Mos by Co, USA, 802-904.

- Tumer A, Sahin S (2011) Risky health behaviors of adolescents. Health and Society 21(1): 32-38.

- Albayrak S, Balcı S (2014) Substance addiction and prevention in young people. Journal of Nursing Education and Research 11: 30-37.

- Grunbaum JA, Kann L, KinchenS, Ross J, Hawkins J, et al. (2004) Youth risk behaviour surveillance-United States. MMWR Surveill Summ 53(2): 1-96.

- Dil S, Gönen Sentürk S, Aykanat Girgin B (2015) Examine the adolescents’ self-esteem and healthy life style behaviours according to their some of socio-demographic characteristics and risky health behaviours. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry 16: 51-59.

- Metinoglu İ, Pekol S, Metinoglu Y (2012) Factors affecting the prevalence of obesity in students between the ages of 10-12 in Kastamonu, Acıbadem University. Journal of Health Sciences 3: 117-123.

- Aksoydan E, Çakır N (2011) Evaluation of nutritional behavior, physical activity level and body mass index of adolescents. Gülhane Medical Journal 53: 264-270.

- Zhang JJ, Li NX, Lıu CJ (2010) Associations between poor health and school-related behavior problems at the child and family levels: a crosssectional study of migrant children and adolescents in southwest urban China. Journal of school health 80(6): 296-303.

- Gumus Dogan D, Ulukol B (2010) Factors contributing to smoking and efficiency of two different education models among adolescents. Journal of Inonu University Medical Faculty 17: 179-185.

- Sevil Ü, Coban A, Tascı E (2006) High school students’ health promotion behaviors. Dirim 81: 255-267.

- Bleakly A, Ellis J (2003) A role for public health research in shaping adolescent health policy. American Journal of Public Health 93(11): 1801-1802.

- Chen MY, Wang EK, Yang RJ, Liou YM (2003) Adolescent health promotion scale: development and psychometric testing. Public Health Nursing 20(2): 104-110.

- Aras S, Gunay T, Ozan S, Orcın E (2007) Risky behaviors of high school students in İzmir. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry 8: 186-189.

- Bayık Temel A, BaflalanIz F, Yıldız S, Yetim D (2011) The Reliability and Validity of Adolescent Health Promotion Scale in Turkish Community. Journal of Current Pediatrics 9: 14-22.

- Karadamar M, Yigit R, Sungur MA (2014) Evaluation of Healthy Life style Behaviours in Adolescents. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry 17: 131-139.

- Aytekin A (2005) Self-actualization and religiosity: a research on university students. M.U. Theology Faculty Journal 29(2): 185-204.

- Turan T, Ceylan SS, Cetinkaya B, Altundag S (2009) The determine of frequency and factors influencing obesity and dietary pattern in vocational high school students. TAF Preventive Medicine Bulletin 8(1): 5-12.

- Govender K, Naicker SN, Meyer Weitz A, Fanner J, Naidoo A, et al. (2013) Associations between perceptions of school connectedness and adolescent health risk behaviors in South African high school learners. Journal of School health 83(9): 614-622.

- Karadeniz G, Yanıkkerem Ucum E, Dedeli O, Karaagaç O (2008) Healthy life style behaviors of university students. TAF Preventive Medicine Bulletin 7(6): 497-502.

© 2018 Anagha Abhoy Sinha. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)