- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Nurses' Spiritual Well-Being and Patients' Spiritual Care in Iran

Sepideh Jahandideh1*, Azam Zare2, Elizabeth Kendall1 and Mina Jahandideh3

1Griffith University, Australia

2University of Tarbiat Modares, Iran

3Zanjan University, Iran

*Corresponding author: Sepideh Jahandideh, Menzie Health Institude, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia, Tel: +617469304419; Email: sepieh.jahandideh@griffithuni.edu.au

Submission: December 18, 2017; Published: January 16, 2018

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

Spirituality is known to play a significant role in patients' well-being and quality of life. Responding to patients' spiritual needs is considered to be an essential element of high quality medical care. Consequently, it seems logical that there is a professional requirement for nurses to achieve competence in the delivery of spiritual care. This study aims to examine the impact of nurses' spiritual well-being on patients' spiritual care. A total of 210 nurses working in critical care units completed Basic Psychological Needs questionnaire and Spiritual Care Competence Scale. 5.8% of nurses provided spiritual care at a poor level; 53.4% at an optimal level; and 39.8% at a highly desirable level. There were negative significant relations between the average scores of spiritual well-being with: age (p<0.04); and clinical experience (p<0.02). There were positive significant relations between the receipt of training by nurses in the principles of spirituality with: the level of spiritual well-being (p<0.003); and the level of spiritual care (p<0.02). Overall, a significant relationship was observed between spiritual well-being and spiritual care (p<0.001). The study has demonstrated that there was a positive relationship between nurses' spiritual well-being and the provision of spiritual care. Implementation of strategies that might develop spiritual well-being in nurses would be of great benefit in catering for the spiritual needs of patients.

Keywords: Spiritual well-being; Spiritual care; Nursing; Critical care units

Introduction

Iran is one of the most religious countries in the world. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is a strong relationship between spiritual health and quality of life in patients with chronic diseases and elderly people [1-3]. The delivery of spiritual care is likely to be of more importance in this country than elsewhere. Even in less religious countries, it has been found that the spiritual needs of people with chronic pain diseases are moderately associated with both positive and negative interpretations of their illness [2]. Thus, the way in which patients view their disease is likely to have a profound impact on their psychosocial and physical health. Human beings are multi-dimensional creatures. They have a broad range of physical, psychological, social, emotional, intellectual, developmental, cultural and spiritual needs [4]. Research has shown that spirituality plays a substantial role in health, well-being and quality of life [1,5,6].

There are different meanings for the term "spirituality" and it can mean different things to different people. It may comprise one's beliefs and values; a sense of meaning and purpose in life; a sense of connectedness; identity and awareness; and, for some people, religion [7,8]. Meeting the spirituality needs of patients and their families has been considered to be a basic element of clinical care [8]. Emphasis has been placed on holistic nursing care that integrates body, mind and spirit. Spiritual care has, therefore, become a main component of nursing performance, an essential part of care delivery and a unique aspect of health care services [9].

Florence Nightingale, a pioneer in the emergence of nursing, believed that nurses have an important role, and a responsibility, to promote patients' health by also considering moral and mental aspects of patients' lives as well as their physical needs [10]. Evidence shows that patients believe nurses should be a source of spiritual information and be able to fulfil patients' spiritual needs at times of health crises that require hospitalization (Ramezani et al. 2014). Similarly, nurses are willing to address patients' spiritual needs [11] and are expected to respect these needs in nursing codes of ethics.

Nurses must meet patients' physical, mental, social and spiritual needs to deliver high quality care [12,13]. Matthew [14] also concluded that spiritual care was a part of nursing care and stated that although all Schools of Nursing espouse nursing care in terms of the biological, psychological, social and spiritual, there is usually minimal content focused on spiritual care [14]. The need for spiritual care is often included in the nursing training literature, but only in brief references such as, "pay attention to patients' spiritual beliefs" or through general inclusion as a part of psycho-social cares [14].

Researchers have shown that nurses like to meet patients' spiritual needs, but there is considerable ambiguity about the nature of spiritual care [15,16]. For example, interventions of such care comprise patients’ spiritual and cultural beliefs; communication with them about religious matters; being with them through their care; empathy; providing facilities for participation in religious events; improving their sense of well-being [17,18]. Strang & Ternestedt [11] found that a majority of nurses (87%) stressed the importance of paying attention to these needs, but only 42% of them reported that the staff actually paid attention to spiritual needs in practice [11].

In the early history of nursing, spiritual care has existed in the form of religiosity [19,20]. As time progressed, nursing became more oriented towards task-accomplishment, and the spiritual dimension of care was neglected [13,21].

The spiritual dimension of care was not considered to be relevant to all health and medical services [22]. Nevertheless, nurses who had religious beliefs reported more positive attitudes towards spiritual care and were significantly more likely to practise spiritual care [23,24]. The main aims of this research were to investigate the relationship between nurses' spiritual well-being and the perceived quality of patients' spiritual care in Iran; and to determine relationships between demographic factors and spiritual care provision and spiritual well-being.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the relationship between nurses' spiritual well-being and patients' perceptions of the quality of spiritual care in Shiraz, Iran.

Participants

The participants consisted of nurses who were employed at all levels (head nurses, staff, and nurse aides) within six critical care units (CCUs) and patients currently receiving treatment in those wards. The convenience method was used for sampling. All current nurses and patients employed in, or admitted to, the critical care units of a major hospital in Shiraz between September (2015) and February (2016) were recruited for the study.

In total, 210 questionnaires were delivered to nurses after receiving informed consent, with 180 returning a completed questionnaire. Most of the nurses were female (98%) and 55.35% were in the age range of 26 to 30 year. Most were married (66.3%), almost all of them (93.2%) had a Bachelor of Science in Nursing and only 41% had received training in the area of patient spiritual care. For each nurse who participated in the study, three patients were recruited. All consented patients were given a questionnaire by the principle researcher and informed about the details of study In total 540 patients participated in the study of which 59% of patients were in the age group of 51 and over; 60% of all patients were female. The research protocol has been reviewed for the ethics and methodology by the quality assurance board of the Heart Hospital, Shiraz, Iran.

Measures

The instruments used in this study measured the spiritual health of nurses and the perceived quality of the spiritual care received by their patients. The spirituality well-being questionnaire [25] . Comprises 20 positive statements rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 'completely agree' to 'completely disagree'. Negative statements were reverse coded. The scale contains 2 sub-scales:

a) Religious well-being; and

b) Existential well-being.

Religious well-being refers to the feeling of having a relationship with a superior power, while the existential well-being is interpreted as trying to understand the meaning and purpose of life [24]. Each sub-scale included 10 items which results in a score between 10 and 60. The total spiritual health score is the sum of these two subscales which has a range between 20 and 120. Nurses' responses were divided into three groups; low scores (20-40); moderate (4199) and high scores (100-120) [25]. Higher scores represented higher levels of spiritual health. When tested on a group of nurses, Cronbach’s Alpha for the scale was 0.94 indicating excellent reliability.

The spiritual care competency of the nurses was measured using 27 questions derived from the nursing competency profile [26] . Patients, the Quality Improvement Officer of the hospital, and clinical documents were used to indicate how they estimated nurses' levels of competency in spiritual care. These questions formed six spiritual care competency dimensions. The first dimension, based on six questions, measured assessment and implementation of spiritual care, which refers to the ability to determine a patient's spiritual needs and/or problems and to the planning of spiritual care; the next six questions examined the second dimension, professionalization and improving the quality of spiritual care and includes those activities of the nurse aimed at quality assurance and policy development in the area of spiritual care.

These two dimensions were only completed by the quality improvement officer of the hospital and clinical documents. The personal support and patient counselling dimension (6 questions) was seen as the heart of spiritual care, with questions operationalised in terms of interventions; referral to professionals (3 questions) is the dimension relating to cooperation with the other disciplines in healthcare that are responsible for spiritual care, with the clergy being explicitly referred to; the attitude towards patient spirituality dimension was measured using 4 questions; and lastly contact and communication between nurse and patient was examined via 2 questions. A five-point Likert scale was used (1=strongly disagree to 6=strongly agree), resulting in a maximum score of 168 and a minimum of 27. Spiritual care competency was then divided into three categories, low level (27-74), moderate level (75-121) and high level (122 to 168). When tested on a group of nurses, Cronbach's Alpha for the scale was 0.85 indicating good reliability [26]. Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) was used to analyse data using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results

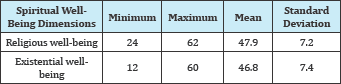

Table 1: The mean and standard deviation of the spiritual wellbeing in nurses.

The findings have shown that 98% of nurses were female; 55.3% ranging in age from 26 to 30 years; 41% of all nurses had more than 5 years clinical experience; 28% of nurses had been trained in spiritual care during their education. Nurses reported mean religious and existential well-being scores of47.95 (SD=7.26) and 46.8 (SD=7.4) respectively, which were in the medium level (Table 1).

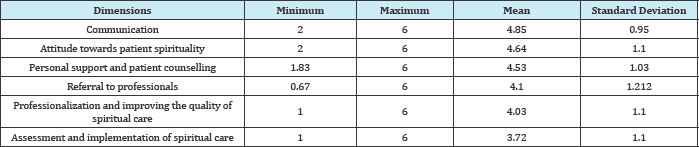

In terms of spiritual care, the highest score was found on the dimension of communication, 4.85 (SD=0.95), while the assessment and implementation of spiritual care dimension achieved the lowest score, 3.72 (SD=1.10) (Table 2). Mean and standard deviation of spiritual well-being and spiritual care were 84.3 (SD=13.1) and 114.2 (SD=22.9) respectively, which are considered to be a medium level (Table 3).

Table 2: The mean and standard deviation of spiritual dimensions of care in nurses.

Table 3: The mean and standard deviation of the spiritual well-being and spiritual care in nurses.

The results revealed that 59.2% of nurses reported a medium level of spiritual well-being and 40.8% reported a high level. According to patients, the spiritual care provided by nurses was mostly at a medium level, with 5.8% at a low level; 53.4% at a medium level; and 39.8% at a high level. Overall, there was a moderate positive relationship between nurses' spiritual wellbeing and the patients' perceptions of spiritual care provided by nurses, using the Spearman test (r=0.60; p<0.001).

In addition, there were negative relationships between nurses' spiritual well-being and age (r = -0.19; p<0.04), and job experience (r= -0.22; p<0.02). However, there was a positive significant relationship between nurses' spiritual well-being and the receipt of training in the principles of spirituality during their education (r= 0.31; p<0.003). There were no significant relationships between spiritual care provision by nurses and demographic factors (age, job experience, the receipt of training in the principles of spirituality during their education, general education).

In considering the relationships between nurses' spiritual wellbeing and the perception of the level of spiritual care provided by nurses, significant positive relationships were found between nurses’ religious well-being and: assessment and implementation of spiritual care (r= 0.280; p<0.004); professionalization and improvement of quality of spiritual care (r= 0.330; p<0.001); personal support and patient counselling (r=0.251; p<0.01); and communication about spirituality (r= 0.347; p<0.000). There was also a positive relationship between nurses' religious wellbeing and patients' reports of referral to other professionals for spiritual guidance (r= 0.347; p<0.023).Similarly, nurses' existential well-being was significantly associated with: assessment and implementation of spiritual care (r= 0.257; p<0.009); professionalization and improvement of quality of spiritual care (r= 0.357; p<0.000); and communication about spirituality (r= 0.383; p<0.000).

Discussion

Nursing provides holistic care that should address patients' physical, mental, social and spiritual health. Our hospital systems cannot ignore spiritual health, but it is frequently overlooked [27]. Nurses in hospitals encounter people at crucial times in their life journey (such as birth, serious injury and death) and these events are historically associated with religious traditions. In this increasingly secular age, nurses need to be aware of how best to address patients’ religious and spiritual needs [28].

Nurses own spiritual well-being is likely to affect the quality of the care they can deliver and the way in which they can meet their patients' spiritual needs. Nurses can provide an appropriate environment to facilitate patients' religious beliefs that may help them in the process of recovery or adjustment. This study has shown that the capacity of nurses to provide high quality spiritual care is related to their own degree of spirituality and their training in spiritual care. This finding is in contrast with the findings of Vance [29] that there was no relationship between spiritual well-being and spiritual care. The researcher found that nurses perceived themselves to be highly spiritual individuals [29]. Yet, it was surprising to find that only slightly more than a quarter of the respondents provided adequate spiritual care to their patients. In examining the barriers to providing spiritual care, the researcher found that time was the greatest barrier. With cutbacks in health care funding, and shortened length of stays, nurses report having to do more with less. They may view spiritual care as a low priority, much like a luxury, and not a necessity for the hospitalized patient [29].

The results of this study suggest that nurses who have religious well-being tend to recognize the spiritual needs of their patients. In contrast, nurses who have a lack of familiarity with spirituality may be less capable of communicating with patients who, in turn, may perceive that nurses are interfering in their religious affairs. If nurses are familiar with religious issues and know it to be part of their job combined with a skill for communicating about religious matters with patients, they will be able to recognize the religious and physical needs of their patients.

In this study, the age and job experience of nurses were inversely associated with their spiritual well-being. In contrast, Boutell & Bozett [30] reported that nurses who were between 50 and 59 years of age tended to be more likely to consider the spiritual needs of patients than nurses in the age range of 30 to 39 years [30]. They also showed that nurses’ job experience was an important factor for predicting spiritual well-being [30]. Wu & Lin [18] revealed that nurses with 11 to 19 years of job experience had higher levels of spiritual well-being compared with nurses who had less job experience. In addition, the current study showed that training in the principles of spirituality during their education contributed to the delivery of spiritual care, a finding that has been shown in previous research [18]. In a study conducted by Wong & Yau [31], nurses stated that spirituality played an important role in healing by contributing to caring relationships and the introduction of hope. These factors can help patients in dealing with the fear and uncertainty that is associated with a hospital admission. However, some nurses worried about having insufficient knowledge and skills to enable them to provide spiritual care [31]. In this research, the lowest score in spirituality care was related to assessment and implementation of spiritual care. As the health system becomes increasingly complex, there is a professional prerequisite for nurses to improve their competence in spiritual care delivery, assessment, and meeting the spiritual needs of their patients [17]. If nurses are able to assess spiritual needs and develop interventions to help patients meet their spiritual needs, they will be able to help promote the quality of life and decrease suffering of patients [32].

Two critical elements are thought to be needed for the provision of adequate spiritual nursing care. The first element is the personal development of a spiritual self. In early research, Lane [33] suggested that the ability to understand, assess and attend to a patient's spirituality is dependent on the nurse's self-awareness of his or her own spirituality through self-reflection. Self-awareness is a prerequisite to the skill of assessment through active listening and articulation of the patient's spiritual needs [33]. The second element is knowledge of culturally relevant spiritual interventions that can meet those needs [34]. The current study has confirmed these important elements, suggesting that there is a need for nurses to be exposed to religious training during their bachelor degrees or as a post-graduate professional development option. If the benefits of spiritual care are to be achieved, particularly in highly religious countries such as Iran, it is critical that the health workforce be able to respond to the holistic needs of patients to promote speedier recovery.

References

- Ali J, Marhemat F, Sara J, Hamid H (2015) The relationship between spiritual well-being and quality of life among elderly people. Holist Nurs pract 29(3): 128-135.

- Büssing A, Koenig HG (2010) Spiritual needs of patients with chronic diseases. Religions 1(1): 18-27.

- Fisch MJ, Titzer ML, Kristeller JL, Shen J, Loehrer PJ, et al. (2003) Assessment of quality of life in outpatients with advanced cancer: the accuracy of clinician estimations and the relevance of spiritual wellbeing- a Hoosier Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 21(14): 2754-2759.

- Ross L, Van Leeuwen R, Baldacchino D, Giske T, McSherry W, et al. (2014) Student nurses perceptions of spirituality and competence in delivering spiritual care: a European pilot study. Nurse Edu Today 34(5): 697-702.

- Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C (2010) The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 24(8): 753-770.

- Yonker JE, Schnabelrauch CA, DeHaan LG (2012) The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. J Adolesc 35(2): 299-314.

- Egan R, Macleod R, Jaye C, McGee R, Baxter J, et al. (2011) What is spirituality? Evidence from a New Zealand hospice study. Mortality 16(4): 307-324.

- McSherry W (2006) Making sense of spirituality in nursing and health care practice: An interactive approach. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK.

- Newman MA, Sime AM, Corcoran-Perry SA (1991) The focus of the discipline of nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 14(1): 1-6.

- Macrae JA (2001) Nursing as a spiritual practice: A contemporary application of Florence. Springer Publishing Company, New York, USA.

- Strang S, Strang P, Ternestedt B (2002) Spiritual needs as defined by Swedish nursing staff. J Clin Nurs 11(1): 48-57.

- Baldacchino DR (2006) Nursing competencies for spiritual care. J Clin Nurs 15(7): 885-896.

- Sawatzky R, Pesut B (2005) Attributes of spiritual care in nursing practice. J Holist Nurs 23(1): 19-33.

- Matthew D (1999) Can every nurse give spiritual care? Kans Nurse 75(10): 4-5.

- Hatamipour K, Rassouli M, Yaghmaie F, Zendedel K, Majd HA, et al. (2015) Spiritual needs of cancer patients: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat care 21(1): 61-67.

- Scheurich N (2003) Reconsidering spirituality and medicine. Acad Med 78(4): 356-360.

- Khoshknab MF, Mazaheri M, Maddah SS, Rahgozar M (2010) Validation and reliability test of Persian version of the spirituality and spiritual care rating scale (SSCRS). J Clin Nurs 19(19-20): 2939-2941.

- Wu LF, Lin LY (2011) Exploration of clinical nurses' perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. J Nurs Res 19(4): 250-256.

- Narayanasamy A, Owens J (2001) A critical incident study of nurses' responses to the spiritual needs of their patients. J Adv Nurs 33(4): 446455.

- Speck BW (2005) What is spirituality? New directions for teaching and learning 2005(104): 3-13.

- Oldnall AS (1995) On the absence of spirituality in nursing theories and models. J Adv Nurs 21(3): 417-418.

- Greenstreet WM (1999) Teaching spirituality in nursing: a literature review. Nurse Educ Today 19(8): 649-658.

- Chan MF (2010) Factors affecting nursing staff in practising spiritual care. J Clin Nurs 19(15-16): 2128-2136.

- Brunner LS, Smeltzer SCC, Bare BG, Hinkle JL, Cheever KH, et al. (2010) Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing Vol 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Paloutzian R, Ellison C (1982) Spiritual well-being scale. Measures of religiosity, pp. 382-385.

- Van Leeuwen R, Tiesinga LJ, Middel B, Post D, Jochemsen H, et al. (2009) The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess nursing competencies in spiritual care. J Clin Nurs 18(20): 2857-2869.

- Swinton J (2001) Spirituality and mental health care: Rediscovering a 'forgotten' dimension. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK.

- Holloway M, Moss B (2010) Spirituality and social work: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vance DL (2001) Nurses’ attitudes towards spirituality and patient care. Medsurg Nurs 10(5): 264.

- Boutell KA, Bozett FW (1990) Nurses’ assessment of patients' spirituality: Continuing education implications. J Contin Educ Nurs 21(4): 172-176.

- Wong KF, Yau SY (2010) Nurses' experiences in spirituality and spiritual care in Hong Kong. Appl Nurs Res 23(4): 242-244.

- Barber JR (2008) Nursing students' perception of spiritual awareness after participating in a spirituality project. College of Saint Mary, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

- Lane JA (1987) The care of the human spirit. J Prof Nurs 3(6): 332-337.

- Conner NE, Eller LS (2004) Spiritual perspectives, needs and nursing interventions of Christian African- Americans. J Adv Nurs 46(6): 624632.

© 2018 Sepideh Jahandideh, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)