- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Analysis of Relationship Between Associate Degree Nursing Student's Self-Confidence In Learning and their Perceived Presence of 5 Instructional Design Characteristics

Geetha Kada*

Montgomery College of Nursing, USA

*Corresponding author: Geetha Kada, Montgomery College of Nursing, MD 20912, USA, Tel: 240-567-5658, Email: geetha.kada@montgomerycollege.edu

Submission: August 16, 2017; Published: January 10, 2018

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

Increasing patient acuity and complex health care demand the need for preparing competent graduate nurses. However, reduced availability of clinical setting exists translating to difficulties obtaining patient care experiences for nursing students. This ongoing issue demands nurse educators to seek alternative teaching strategies. High-fidelity simulation experiences can provide learning environment very similar to the clinical setting. The purpose of this descriptive co-relational quantitative research study was to examine what relationships, if any, existed between associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning and their perceived presence of five instructional design characteristics in a high-fidelity simulation learning experience. The nursing students' perceived experiences were measured by the NLN (National League for Nursing) Self-Confidence in Learning and Simulation Design Survey instruments. Study participants were asked to rate the level of importance of each variable (Self-Confidence and Simulation Design Instruments) on a Likert scale with the following rating: 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree. The results of this study identified students' perceptions on the importance of realism and debriefing (feedback/guided reflection) in a simulation experience. Additional findings highlighted the importance to students of definitive objectives and information, which influence their self-confidence in learning within a simulation learning environment. It is evident the use of simulation as an educational tool is becoming more prevalent in the health care settings. This is especially important in response to the growing shortage of accessible clinical sites and available faculty. The findings of this study support the need for more quantitative research to evaluate the use of high-fidelity simulation experiences on nursing students learning outcomes.

Dissertation Title

Analysis of the relationship between associate degree nursing student's self-confidence in learning and their perceived presence of five instructional design characteristics in a high-fidelity simulation learning experience.

Research Topic

Today's nurses are confronting the enormous amount of challenges in the workplace and are expected to meet these challenges [1]. Harder [2] further noted that the challenge is intensified with increased patient acuity, nursing shortage and technological advancement. Hence, a nurse educator is seeking for alternatives to the clinical setting as a teaching strategy that provides nursing students an opportunity to gain necessary skills [3]. Using high-fidelity patient simulator is an effective teaching strategy that offers nursing students a nonthreatening learning environment, improving their comfort level to care for patients before they encounter real patients. However, attentive designing of a high-fidelity patient simulation experience is needed to provide students an opportunity to demonstrate problem solving and clinical reasoning ability [4]. A well-designed simulation learning experience can guide a nursing student to perceive the characteristics and aspects of real patient situation when it comes to real clinical setting.

This quantitative research study examined the relationship between associate degree nursing students' perceptions of their self-confidence in learning involved with the five instructional design characteristics (objectives and information, support, problem solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) in a high-fidelity simulation learning experience as measured by NLN tool on Self-Confidence in Learning and Simulation Design Scale. This standard NLN evaluation tool was used to assess the nursing students learning outcomes after a simulation experience. Use of this standard tool post- simulation experience describes if simulation experiences, as a learning strategy, improves nursing student's self- confidence and perception of the design characteristics used in high-fidelity simulation. The NLN tool used in this study has been tested multiple times in previous studies with an internal consistency measured by Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 for the presence of features in the simulation design scale and Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 for the self-confidence in learning.

Research Problem

Increasing patient acuity and complex health care environment demand educators to prepare nursing students who can be ready as possible for their clinical experience. High-fidelity patient simulator is one of the best tools to train nursing students to develop higher learning and be competent in the care of complex patients. It provides a real learning environment with real obstacles in which nursing students can apply the nursing care. High-fidelity patient simulator provides a learning environment that is free of distractions and interruptions [3]. While the use of simulation as an educational tool is becoming more prevalent in health care setting, however, studies to evaluate the learning experience of associate degree nursing students in a high-fidelity simulation learning environment continues to be an area requiring research [5].

Also, there are varieties of studies conducted in various populations and in other settings. Therefore, this proposed study was conducted on the nursing students enrolled in an associate degree nursing program. The proposed quantitative research examined the relationship between associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning and their perceived presence of five instructional design characteristics (objectives and information, support, problem-solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) in a high-fidelity simulator learning experience as measured by National League for Nursing (NLN) tool on self-confidence in learning and Simulation design scale.

Definition of Terms

Associate degree nursing students

The students are generally enrolled in the first medical-surgical second semester course from an associate degree nursing program after successful completion of the fundamental nursing course.

High-fidelity Patient Simulator

Walker defined it as a full-sized mannequin that can represent the physical characteristics of an adult patient with preprogrammed human physiology. The human patient simulation (HPS) mirrors real-time human physiology that allows the nursing students to understand various patient clinical conditions that may not be available to them in the real clinical environment.

Learner's Satisfaction

According to Kalisch and Lee & Rochman and Ozturk and Bahcecik & Baumann, it is the degree to which the learner is able to provide maximum care service to the patient with a positive attitude, stay patient focused, and demonstrates the skill to work as a team to care for patients in the complex health care setting.

Learner's Self-Confidence

The degree, to which the learner believes to do what is expected of them, understands the definite patient care process, stays motivated and make appropriate care decisions while caring for their patients without any doubt, reducing medical errors.

Simulation

According to Jeffries & Rogers [6-9], simulation is defined as teaching activities that closely mimic reality to clinical situations and involves various interactive activities that allow students to demonstrate critical thinking and decision-making skills.

Teaching Tool

The nurse educators seek alternative teaching strategy (simulation) to clinical settings that can help the learner’s opportunity to gain the necessary skills to care for the patients [3].

Objective and Information

The students get enough information at the beginning of the simulation experience with clearly listed purposes that can guide the student s performance.

Support

The student’s in the simulation experience get timely help and guidance from the facilitator for an effective learning process.

Problem Solving

The simulation is designed in way that can help the learners to problem solve the situation, prioritize the care and reach the planned goals for the patients.

Feedback/Guided Reflection

The facilitator gives the learners constructive and timely response to their action during the debriefing process that can help the learners to build adequate knowledge and skills to another level.

Fidelity

The real-life factors, conditions, and variables used to build the simulation experience that will help the learners to relate their experience to the real clinical situations.

Need For the Study

Alfes [10] found high fidelity simulation could be used for beginning nursing students to prepare them to communicate effectively and provide comfort care measures to patients. Further, Brewer [3] stipulated the use of high-fidelity patient simulators provides a learning environment that is free of distractions and interruptions. Yet, Alfes [10] indicated the need for more research to support the need for simulation as a learning strategy for nursing students. According to Murray, high-fidelity patient simulator is an effective teaching strategy offering nursing students a nonthreatening learning environment improving their comfort level to care for patients before they encounter real patients.

Moreover, nursing students who are comfortable and satisfied with the design characteristics of a simulation learning environment think critically know what is expected of them, make appropriate care decisions while caring for their patients and are able to set goals for their patients. In addition, debriefing after a simulation experience describes an analysis of a situation helping the nursing students to develop the knowledge and understanding of the appropriateness of actions and identification of strategies for future application in similar situations. However, nurse educators must be equipped with a valid and reliable tool to measure student s learning outcomes and their confidence level in learning in a high- fidelity patient simulation environment [11].

This proposed study will add to the body of knowledge for nurse educators to identify the degree to which five instructional design characteristics of a high-fidelity simulator learning experience relate to associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning experience as measured by the National League for Nursing (NLN) tool on self-confidence in learning and Simulation design scale.

Research Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the degree to which five instructional design characteristics (objectives and information, support, problem-solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) of a high-fidelity simulator learning experience relate to associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning experience as measured by National League for Nursing (NLN) tool on self-confidence in learning and Simulation design scale.

Research Question(s)

What is the relationship between associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning and their perceived presence of 5 instructional design characteristics (objectives and information, support, problem solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) in a high- fidelity simulator learning experience.

Methodology

A co-relational quantitative research study was used to examine the relationship between the degree to which five instructional design characteristics (objectives and information, support, problem-solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) of a high-fidelity simulator learning experience relate to associate degree nursing students’ self-confidence in a learning experience as measured by National League for Nursing (NLN) tool on selfconfidence in learning and simulation design scale. The NLN tool used in this study has been tested multiple times in previous studies with an internal consistency measured by Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 for the presence of features in the simulation design scale and Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 for the self-confidence in learning.

After approval from the school's IRB (Institutional Review Board) and the nursing director of associate degree nursing program in Maryland, the researcher gained consent from the second- semester associate degree nursing students to complete the research instrument post-high-fidelity patient simulation experience. As a part of the course, all students were expected to participate in high-fidelity patient simulation experience. However, the study participants completing the research instrument post high-fidelity simulation experience were given a designated number as an identifier and the same was used throughout the research study. During the scheduled on-campus days, second-semester associate degree nursing students were scheduled to complete simulation experience in the simulation laboratory. Following participation in the simulation scenario, and a debriefing, the study participants were invited to complete the instruments (National League for Nursing Self-Confidence and Simulation Design Scale) for the research study.

Population and Sample

The second-semester associate degree nursing students were drawn from the characteristics of the larger population from where the study was conducted. According to the associate degree nursing program enrolment status in Maryland, an average of 90100 students completes the fundamental course successfully and enrol in the first medical-surgical nursing course.

The sample size was based on the expected confidence level, desired precision of the research findings, and the degree of variability. The confidence level was set at 95%, so that 95 out of 100 samples would have the potential for the true population value within the range of precision specified (±5%). During the course of study, the actual student enrolment was 43 students in the first medical-surgical nursing course, 5 students dropped from the course before participating in the simulation experience. The remaining 38 students completed the NLN instrument after the simulation experience and debriefing. The study participants were between the ages of 18-65 years and were enrolled in the first medical-surgical nursing course.

A nonprobability convenience sampling method was used. This method provided easy access to the study participants and the study included learners who were willing to participate.

Data Collection Procedures

This research study was conducted at a community college located in the south-east region of the United States on the associate degree nursing students during the scheduled on-campus labs. The second semester clinical group of students (first medical- surgical nursing course students) came to the college during their scheduled on-campus lab days for the simulation experience. The simulated experience was facilitated by the respective clinical instructor for the clinical groups. Following the simulation experience, the study participants completed the post simulation instrument/survey in a classroom at the community college. To have access to the study participants in the simulation lab, the researcher conducted the study in her own educational institution. Confidentiality and anonymity was maintained with the use of a research assistant assigned who met with the participants, provided informed consent data, answered study participant questions, and then administer and collect the surveys with identification number. Any student identifiers were removed and the data analyzed and reported in the aggregate.

After the approval from the school's IRB and the nursing director of the associate degree nursing program in Maryland, the researcher gained consent from second-semester associate degree nursing students to complete the research instrument (National League for Nursing Self-Confidence and Simulation Design Scale) post-high-fidelity patient simulation experience. The consent letter explained the purpose of the research, the length of the study, the process of the study, who were involved in the study, how the confidentiality of the study information was maintained, who could be approached for any concerns or questions and if the nursing student want to be a part of the study. Following the consent letter, the associate degree nursing students were informed that as a part of the course requirement, all students will participate in the high- fidelity patient simulation learning experience. The simulation learning experience was mandatory, but participation in research study was not.

The study participants completed the NLN tool post-simulation experience who were given a designated number as an identifier, which was used throughout the research study. The second- semester nursing students participated in the high-fidelity patient scenario simulation experience during their scheduled on-campus lab day. The study was conducted over three-week period when the students had their scheduled on-campus labs. Following participation in simulation scenario, and a debriefing, study participants were invited to complete the instruments (National League for Nursing Self-Confidence and Simulation Design Scale) for the research study immediately after the simulation experience.

The researcher analyzed the data with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for windows. The data were prepared and analyzed after the study participants completed the research instrument post high-fidelity patient simulation experience. The relationships between associate degree nursing students’ selfconfidence in learning and their perceived presence of the five instructional design characteristics (objectives and information, support, problem solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) in a high-fidelity simulation learning experience was analyzed. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) was first employed to answer each research question followed by further statistical analyses including correlations and regression models.

Data Analysis and Results, Conclusion and Summary

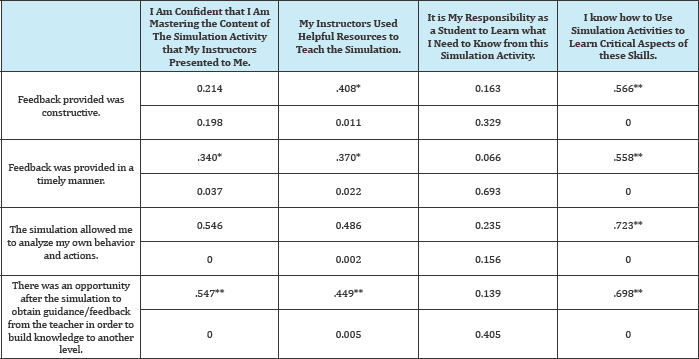

Evaluating the use of simulation with beginning nursing students, Alfes [10] recommended incorporating simulation in the nursing curricula for all nursing learners. Today's health care setting demands newly graduated nurses who are confident and can handle real-life situations dealing with patients and their illnesses. A nursing learner who is confident can engage in challenging goals and commits to achieve those goals successfully [12-14]. Results of this study concluded that students consider the importance of realism and debriefing (feedback/guided reflection) in a simulation experience. The study results also concluded that having definite objectives and information can predict nursing student’s selfconfidence in learning in a simulation learning environment. A few tables below are presented to explain the findings of the study (Table 1 & 2). Table 2 data displays the correlation between SelfConfidence in Learning and fidelity/realism component section in the SDS. The Fidelity (Realism) correlations noted two items of the Self-Confidence of Learning with positive relationships and significance (Table 2).

Table 1: Pearson product-moment correlations between feedback/guided reflection component section in the simulation design scale and self-confidence in learning, question 2.

Table 2: Pearson Product-Moment Correlations between Self-Confidence in Learning and Fidelity (Realism) Component Section in the Simulation Design Scale (SDS), Question 2.

They were associated with "my instructors used helpful resources to teach the simulation and I know how to use simulation activities to learn critical aspects of these skills." Though the two items of "The scenario resembled a real-life situation and Real life factors situations, and variables were built into the simulation scenario" were positively correlated with three of the items from the "Self-Confidence of the Learner", as indicated in Table 2 above, when the normalcy distribution of the data in the specific sections was tested with the Kologorov-Smirnov test the result was to reject the null hypothesis for Fidelity/Realism, which could be due to the factor of only two statements in that component section were available to answer with a high mean of 0.4355 (Table 3).

Table 3: Regression for Association Between Means of Self-Confidencea and Simulation Design Scale Component Sections, Question 3.

The results of the regression model in Table 3 data demonstrated that only one of the component sections in the Simulation Design Scale was significantly associated with the Self-Confidence in Learning Tool. The component section of "objectives and information" was significantly associated at 0.025 with odds of 1.362. Therefore, the items within the component section, as an overall mean of "objectives and information" were 1.362 times (based on odds ratios) more likely to help the students be selfconfident overall in the simulation activities [15-19].

Subsequent, each component section ‘item’ within the Simulation Design Scale was entered to determine any associations with the individual statements (four specific statements in the SelfConfidence in Learning) tested for predictive association. Multiple regression and logistic regression techniques were used. First, multiple regression was used to test for any predictive associations between the Self-Confidence in Learning and the five components of the Simulation Design Scale. Backward stepwise regression modeling was use due to the modest number of variables and the ability to investigate the individual variables as well as subsets (Table 4).

In the multiple regression data in Table 4, the significance, odds ratios, and confidence intervals were reported. It was found that students' perceived the simulation design to be specific for their level of knowledge with a significance of 0.036, however the odds ratios did not support the predictive association (as reported in EXP (B)). To analyze these variables for increased predictive associations' the Unstandardized Beta Coefficient was used to calculate odds ratios. Odds ratios represent the odds of something occurring when the outcome has been exposed to an intervention or event. Odds ratios are noted generally within a logistic regression model; however, odds ratios can be calculated based on the Unstandardized Beta Coefficient and represent the increase in per unit change of a value from an intervention or event (exposure of the dependent variable from other independent variables). Therefore, it provides the odds of an event or change occurring based on the impact of the independent variables on the dependent variable [20-22].

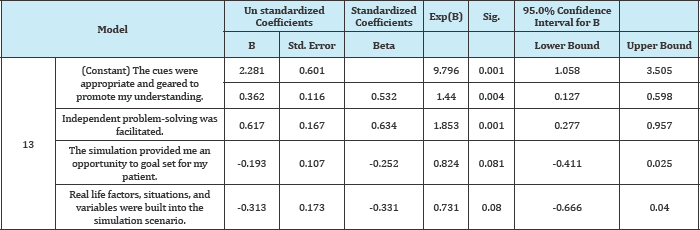

Table 4: Regression: Outcomes on “My instructors used helpful resources to teach the simulation” Question 3.

The second statement in Self-Confidence in Learning tested was: My instructors used helpful resources to teach the simulation. Multiple regressions modelling (see Table 4) was used with all items in the Simulation Design Scale. Odds ratios were calculated and inserted within the table. The regression model ran for 13 steps. In the following regression table, there are two predictive associations noted. They are: (a) the cues were appropriate and geared to promote my understanding, and (b) independent problem solving was facilitated. Therefore, utilizing odds ratios, students were 1.440 times more likely to feel that the instructor used helpful resources as cues geared to promote their understanding with a significance of .004 and a confidence interval of .127-.598. The second significant finding was the students were 1.853 times more likely to feel the instructor used helpful resources to facilitate independent problem solving.

The research hypothesis for this study was: There is a statistically significant relationship between the associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning and their perception of the presence of five instructional design components (objectives and information, support, problem solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) in a high-fidelity simulation learning experience [23-26].

The results of the study showed that four (support, problem solving, feedback/guided reflection and fidelity/realism) of the five component sections of the Simulation Design Scale did not support the directional research hypothesis when the means were tested for any predictive association with the Self-Confidence in Learning Survey [27,28]. The results of the regression model (see Table 3) noted one of the component sections in the Simulation Design Scale was significantly associated with the Self-Confidence in Learning Surveys (based on the means of each of the component sections in the Simulation Design Scale). The component section of "objectives and information" was significantly associated at 0.025 with an odd of 1.362. Therefore, the items within the component section, as an overall mean of "objectives and information" were more likely to help the students be self-confident overall in the simulation activities.

When the individual items in the SDS were tested with the four individual statements in the Self-Confidence in Learning Survey, three of the four statements supported predictive associations within the regression model. The three statements were: I am confident that I am mastering the content of the simulation activity that my instructor presented to me; my instructors used helpful resources to teach the simulation, and it is my responsibility as the student to learn what I need to know from this simulation activity.

The null hypothesis for this study was: There is no statistically significant relationship between associate degree nursing students' self-confidence in learning and their perception of the presence of five instructional design components (objectives and information, support, problem solving, feedback/guided reflection, and fidelity/ realism) in a high-fidelity simulator learning experience. Of the four statements tested from the Self-Confidence in Learning Survey with the items within the component sections of the Simulation Design Scale the statements of "I know how to use simulation activities to learn critical aspects of these skills" was not significant within the regression modeling.

The results of the study did not support the research hypothesis when the means were tested for any predictive association with the Self-Confidence in Learning survey and the means of the categories in the Simulation Design scale (SDS). However, when the individual items in the SDS were tested with four individual statements in SelfConfidence in Learning, three of the four statements supported predictive associations within the regression modelling [28].

While the use of simulation as an educational tool is becoming more prevalent in the health care setting, studies to evaluate learning experience of nursing students in a high-fidelity simulation learning environment continue to be an area requiring research. Thus, more quantitative research is recommended to evaluate the use of high-fidelity simulation experience on nursing students learning outcomes.

References

- Larew C, Lessans S, Spunt D, Foster D, Covington BG, et al. (2006) Innovations in clinical simulation: Application of Benner's theory in an interactive patient care simulation. Nurs Educ Perspect 27(1): 16-21.

- Harder BN (2010) Use of simulation in teaching and learning in health sciences: A systematic review. J Nurs Educ 49(1): 23-28.

- Brewer EP (2011) Successful techniques for using human patient simulation in nursing education. J Nurs Scholarsh 43(3): 311-317.

- Crouch L (2009) Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of the simulation design, learning, satisfaction, self-concept, and collaboration in high-fidelity human patient simulation.

- Smith SJ, Roehrs CJ (2009) High-fidelity simulation: Factors correlated with nursing student satisfaction and self-confidence. Nurs Educ Perspect 30(2): 74-78.

- Jeffries PR (2005) A framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating simulations used as teaching strategies in nursing. Nurs Educ Perspect 26(2): 96-103.

- Jeffries PR (2006) Designing simulations for nursing education. Annual Review of Nursing Education 4: 161.

- Jeffries PR (2007) Simulation in nursing education: From conceptualization to evaluation. National League for Nursing, New York, p. 168.

- Jeffries PR (2008) Getting in S.T.E.P. with simulations: simulations take educator preparation. Nursing Education Perspectives 29(2): 70-73.

- Alfes CM (2011) Evaluating the use of simulation with beginning nursing students. J Nurs Educ 50(2): 89-93.

- Adamson KA (2011) Assessing the reliability of simulation evaluation instruments used in education: A test of concept study. ERIC.

- Ackerman Barger PW (2010) Embracing multiculturalism in nursing learning environments. J Nurs Educ 49(12): 677-682.

- Aldrich C (2005) Learning by doing: A Comprehensive guide to simulations, computer games, and pedagogy in E-learning and other educational experiences. John Wiley & Sons, San Francisco, USA.

- Alinier G (2011) Developing high-fidelity health care simulation scenarios: A guide for educators and professionals. Simulation & Gaming 42(1): 9-26.

- Allchin L (2006) Caring for the dying: Nursing student perspectives. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 8(2): 118-119.

- Brooks N, Moriarty A, Welyczko N (2010) Implementing simulated practice learning for nursing students. Nurs Stand 24(20): 41-45.

- Brown JF (2008) Applications of simulation technology in psychiatric mental health nursing education. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 15(8): 638-644.

- Cato ML, Lasater K, Peeples AI (2009) Nursing students' self-assessment of their simulation experiences. Nurs Educ Perspect 30(2): 105-108.

- Creswell JW (2009) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach (3rd edn). Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, CA, USA.

- Davis AH, Kimble LP (2011) Human patient simulation evaluation rubrics for nursing education: Measuring the essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. J Nurs Educ 50(11): 605611.

- Decker S, Sportsman S, Puetz L, Billings L (2008) The evolution of simulation and its contribution to competency. J Contin Educ Nurs 39(2): 74-80.

- Dreifuerst KT (2009) The essentials of debriefing in simulation learning: A concept analysis. Nurs Educ Perspect 30(2): 109-114.

- Lasater K (2007) High-fidelity simulation and the development of clinical judgment: Students' experiences. J Nurs Educ 46(6): 269-276.

- Laschinger S, Medves J, Pulling C, McGraw DR, Waytuck B, et al. (2008) Effectiveness of simulation on health profession students' knowledge, skills, confidence and satisfaction. Int J Evid Based Healthc 6(3): 278302.

- Spencer C (2011) The impact of simulation on the acquisition of critical thinking skills in nursing students enrolled in an associate degree program.

- Weaver A (2011) High-fidelity patient simulation in nursing education: An integrative review. Nursing Education Perspectives 32(1): 37.

- Wotton K, Davis J, Button D, Kelton M (2010) Third-year undergraduate nursing students' perceptions of high-fidelity simulation. J Nurs Educ 49(11): 632-639.

- Wright K (2010) Do calculation errors by nurses cause medication errors in clinical practice? A literature review. Nurse Educ Today 30(1): 85-97.

© 2018 Geetha Kada. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)