- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Recording Recovery Opportunities at Work and Functional Fatigue after Work: Two Instruments Adapted to the Swedish Context

Kerstin Wentz1*, Kristina Gyllensten1 and Trevor Archer2

1Department of Psychology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden

2Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

*Corresponding author:author: Kerstin Wentz, Department of Psychology, Psychologist Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden, Tel: 46 (0)31 786 3219; Email: kerstin.wentz@amm.gu.se

Submission: October 27, 2017; Published: December 06, 2017

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume1 Issue2

Abstract

Objectives: The importance of considering need for recovery after work and recovery opportunities at the workplace is relevant for occupational groups supporting clients in the workplace. Therefore, it is important that these concepts may be estimated with valid and reliable instruments within also a Swedish context. Thus, the aim of the study was to adapt the Need for Recovery (NFR) scale and the Recovery Opportunities (RO) scale to Swedish conditions and to assess the psychometric properties of the scales.

Material and methods: The translation process followed the guidelines for cultural adaptation of questionnaires. Both the RO scale and the NFR scale were assessed for stability, internal consistency and validity (n=146) in accordance with the validation of the original Dutch scales. An exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation was performed regarding both scales. An Eigenvalue greater than one was used to determine number of factors.

Results: The validity of the control scale RO in terms of the NFR value correlatively linked detachment from work to recovery from work demands. Regarding NFR, RO was more important than the other control scales. Work demands were negatively correlated with RO and an Influence control scale. Sufficient psychometric properties were found for both the NFR and the RO scales with stability measures (ICC) exceeding 0.90 and with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.80 for RO and 0.90 for NFR. Principal component analysis showed meaningful results and regarding NFR confirmed earlier Dutch findings.

Conclusion: Both scales proved to be reliable instruments to evaluate recovery opportunities related to work shifts and work-related fatigue after the shifts. The instruments confirmed findings from other countries regarding meaningful correlations with well-established instruments. The two instruments together confirm the importance of detachment from work for health benefit.

Introduction

Stress is estimated to be the most common reason for workers taking sick leave in Sweden [1]. Simultaneously, and from the perspective health it has been suggested that insufficient recovery from stress is a bigger problem than the actual load from stress itself [2]. The specific challenge of recovering from work demands has been condensed into an estimation of the need for recovery after work (NFR) in terms of fatigue appearing at the end of an ordinary work shift. NFR appears as feeling of congestion and irritability and also involves a decrease in performance and energy level [3]. Importantly, this specific type of uneasiness at the end of work shifts has been found to be distinguished from common mental health problems by [4].

Some degree of functional fatigue after work is identifiable among nearly all employees, but for the individual to meet the demands of the upcoming work shifts he or she has to be able to regain the resources consumed during the shift [4]. This restoration of resources is carried out through a day-to-day recovery process [5]. If this daily recovery process is not fully completed, an accumulation of strain occurs. Over time, a lagging residual of strain implies also that the reversibility of fatigue after work becomes less likely [6]. Kiss [7] has suggested that a measure of work- related fatigue could be viewed as an early indicator of negative health effects. In parallel, Sluiter [8] found that need for recovery was a major predictor of health complaints. Also, besides being an early indicator of future health problems, work-related fatigue has documented negative effects upon safety in the workplace, as reported by Swaen [9] & Kecklund [10].

Demanding labor situation affects health, first as an increased need for recovery. Indeed, a greater need for recovery is expected to double the risk of long sick leave two years later [11], and prospective studies have shown that it is also a valid predictor for cardiovascular diseases [12] and psychosomatic complaints [6,13]. Aronsson [14] studied the working conditions, individual strategies, recovery, and health of public employees, and found that the risk of health problems among insufficiently recovered employees was 2-18times higher when compared to sufficiently recovered employees. Conversely, substantial actions taken to increase and improve recovery among coach drivers showed a good effect on need for recovery after work fatigue, emotional exhaustion, and physical problems [15].

The need for recovery depends not only on the working conditions but also on age [7]. Recovery from work demands can be divided into two different types. These types concern either job design, for example, allowing workers to control longer or shorter breaks during work shifts, or time off from work [16]. Regarding leisure time recovery, Sonnentag [17] documented that social activity, low effort (passive) activity, and physical activity were beneficial. In addition, Sonnentag [17] points out that the negative effects from time pressure at work mainly unfold during leisure time, thereby affecting the recovery process as measured by wellbeing at bedtime. Also, the finding by Fransson & Heikkilä [18] suggests that unfavorable work characteristics affect the feasibility of leisure time recovery by increasing the risk of physical inactivity With regard to after-effects from high workload impinging the recovery process, researchers such as Frankenhaeuser [19], Meijman [20], have documented how a high workload correlates with pronouncedly elevated adrenaline excretion rates during leisure time.

Patterns of high workload accompanied by an increased risk for both physical [21] and mental health problems [22,23] have been documented. Simultaneously, these kinds of processes may prove themselves at early stages. This important phenomenon provides a rationale for using the signaling effect from an increased need for recovery as a preventive measure for antecedents of physical and mental health problems [6]. Put differently, the work shift may be used as a litmus paper on health.

Critical care nurses constitute one of several professions at risk for burnout and secondary trauma-components of compassion fatigue, as a consequence of the high-pressure work environment. Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue influence nurses' intention to continue within their chosen professions. It was observed among critical care nurses' profiles that, whilst not in crisis, did not attain optimal levels of high compassion satisfaction and moderate/low fatigue although these individuals were not at crisis Jakimowicz [24] nevertheless, they remain at higher risk for compassion fatigue with necessity for improved postgraduate education. The relevance of meaningful recognition tools and other predictors of compassion fatigue have been assessed [25]. They obtained an equivalent extent of burnout, secondary traumatic stress, compassion satisfaction, overall satisfaction, and intent to leave from nurses serving in hospitals with and without meaningful recognition programs. However, meaningful recognition predicted decreased burnout and increased compassion satisfaction whereas job satisfaction and job enjoyment assessments predicted decreased burnout, decreased secondary traumatic stress, and increased compassion satisfaction.

There are several questionnaires that may be used to measure need for recovery. For example, Aronsson & Astvik [14] used eight items to measure unwinding and recovery in a study with employees within pre-school, home care and social work in Sweden. The items reflected daily recovery and recovery during vacations. The need for recovery scale (NFR) is one of the main scales used to assess work-induced fatigue and quality of recovery time. It was developed in the Netherlands and has been used in occupational health practice and academic research in many studies [3,26]. Moreover, it has been translated into several languages and used in academic research in countries, such as Brazil and Italy [27,28].

One of the most relevant factors influencing recovery from work is the level of control over recovery opportunities during work shifts including the interface between the shifts and the personal sphere [16]. The recovery opportunities scale (RO) assesses workers' opportunities to take breaks, pauses and days from work. It aims at situational characteristics that enable individuals to recuperate from work effort. Both the NFR and the RO scales have been used with different occupations and have been found to have good reliability and validity [3,5,29].

Despite the large number of studies using these scales an examination of the literature indicated that, to date, no studies have adapted the scales to the Swedish occupational context.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to translate and adapt the NFR and RO to the Swedish language. The translation was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for cross- cultural adaptation of self-report measures on health proposed by Beaton [30]. The validity of the scales was explored by testing the correlations between the Swedish versions of the RO and NFR and the Demand Control Questionnaire [31], Influence at Work scale and the Possibilities for Development scale both from the Copenhagen Psycho Social Questionnaire [32], the single-item version of the Work Ability Index [33] and the Vitality scale from SF-36 [34]. The reliability of both scales was tested through Cronbach’s alpha, the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), the split half reliability, items-total correlation, and alpha-if-item-deleted. Additionally, exploratory factor analyses were performed.

Methods

Procedure

This study was performed in two stages. In the first stage, the two scales NFR and RO, were translated into Swedish and culturally adapted to the Swedish environment. In the second stage, the scales were tested among a larger group of employees to assess the reliability and validity of the scales for application among Swedish employees.

Cross-cultural adaptation process

The Swedish version of the NFR is called "Behov av återhämtning”, and RO is called "Återhämtningsmöjligheter” Both scales were translated from the original Dutch versions of the scale. The translation was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures on health proposed by Beaton [30]. According to the authors, the term "cross-cultural adaptation" involves a process that considers both language and cultural adaptation issues. Five stages are recommended in this process: initial translation, synthesis of the translations, back translation, expert committee, and pretesting. The initial translation into Swedish was performed individually by three professional translators. One of the translators was aware of the concepts investigated by the questionnaire, and two of the translators were naive translators (not aware of the concepts and no background in the psychological/medical field).

Two of the translators and a recording observer (KW) synthesized the results of the translations into one common version of the scales. This version was then re-translated into Dutch by two other naive translators. At this point the original authors of the questionnaires were invited to comment on the back translations. At the next stage, an expert committee consisting of five experts was nominated-one Swedish language professional/ researcher, one Dutch language professional/researcher, one bilingual translator, one child psychologist with knowledge of the Dutch language, and the two authors. The committee reviewed and compared the common translations, the back translations, and the original scales. Decisions were made on the basis of semantic equivalence, idiomatic equivalence, experiential equivalence, conceptual equivalence, and simplicity, and pre-final version of the scales were developed. Written recordings from the earlier stages of the adaptation process were used during the committee meeting, which was also recorded, aiming at the adaptation process ahead.

Pretesting was performed to verify whether the Swedish version of the scales was equivalent to the original scales and whether the target group would understand it accurately. Beaton [30] recommended a sample of at least 30 workers be taken in this stage. Overall, a sample of 32 workers with different levels of education (8 men and 24 women, mean age 45 years) were asked to read the scales, fully explain their answers, and report any difficulty. Beaton's [30] recommendation is that if 15% of the participants have difficulty understanding the questions, or if the interpretations of the questions do not have the same meaning as in the original scale, the questions be reformulated. This was the case for one of the questions in the RO referring to whether the worker can be called in on a day off. This question was subsequently revised slightly.

Psychometric testing

To test the psychometric properties of the Swedish final versions of the Swedish NFR (Sw-NFR) and Swedish RO (Sw- RO) scales, a sample of participants from different occupational groups were invited to participate. Overall, 200questionnaires were distributed to workers via union representatives. The union representatives received 25 questionnaires each, which they distributed to workers within different occupations, including cemetery workers; emergency services personnel, postal workers, assistant nurses, and registered nurses. Instructions on how to complete the questionnaire were included in the document together with a stamped return envelope addressed to the researchers. In addition, 120 of the participants were invited to complete the questionnaires twice. The interval between the tests was one week, as recommended by Terwee [35].

Measures

NFR is a dichotomous scale that consisted of 11 items. In the Swedish version the dichotomous answers from the original scale were changed to: 0=never, 1=sometimes, 2=often, 3=always. "Always" indicates an unfavorable situation, except for item 4, where the scoring is reversed. The total score ranges from 0 to 33, where higher scores indicate a higher need for recovery. The RO consists of 9 items with answering categories never, sometimes, often, always scored 0-3. The total score ranges from 0 to 27 and a higher score indicate a higher level of recovery opportunities. Typical items of the NFR are 'At the end of the working day I am really feeling worn-out' and I find it hard to relax at the end of a working day"? Typical items of the RO include "Can you interrupt your work if you find it necessary to do so' and "are your working hours arranged well?"

Job demands were measured by the Demand subscale (5 items) from the Demand Control Questionnaire [31]. This demand scale mirrors load from work in terms of quantitative demands, speed, and time pressure.

Control was measured by several scales. The Swedish version of the Control scale (6 items) was derived from the Demand Control Questionnaire [31]. This control instrument assesses monotony, professional developmental opportunities, and influence over work task. Two further control scales were selected from the Swedish version of the Copenhagen Psycho Social Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [32]. The Influence at Work scale (4 items) assesses influence concerning the work situation, including the choice of with whom to work and the content of work. The 'Possibilities for Development scale’ (5 items) mirrors professional developmental opportunities.

The Vitality scale (4 items) from SF-36 [34] was used to measure health. Vitality is operationalized in terms of having experienced alertness and strength, having felt energetic, and conversely, and having felt worn out. The single-item version of the Work Ability Index [33] was included to measure work ability. This single item, with a range of scores from 1 to 10, rates current work ability in comparison to lifetime best work ability.

Participants

The study sample size was estimated on the basis of Terwee [35] suggestion that at least 50 participants were necessary for reliability and construct validity and at least 100 participants for internal consistency. The participants were recruited from four different professions in terms of assistant nurses, cemetery workers, postal employees and hospital nurses. Two hundred questionnaires were packed in bundles of 25 and distributed to union safety officers. The authors were known to the safety officers due to educational activities. During the first test round 173 questionnaires were distributed at the work places. During the retest round 118 questionnaires were distributed (see Stability test-retest). The hospital nurses were only asked to participate in the first round. In total 142 participants completed the Sw-RO, 38 men and 103 women, mean age 46 years (SD=12). One participant did not complete details regarding age and gender but completed the rest of the questionnaire and was therefore included in the analyses. Overall, 146 participants completed the Sw-RO, 38 men and 108 women, mean age 46 years (SD=12). In addition, 84 participants answered the Sw-RO and Sw-NFR twice.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows.

Validity of the swedish recovery opportunities (Sw-Ro) scale

To assess convergent construct validity of the Sw-RO, the participants were asked to complete the Swedish version of the control scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire [31] at the same time as they completed the Sw-RO. The scale was expected to show a positive correlation with the Sw-RO.

To assess convergent construct validity of the Sw-RO, the participants were asked to complete the Control scales influence and developmental opportunities from the Copenhagen Psycho Social Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [32] at the same time as they completed the Sw-RO. Both COPSOQ scales were expected to show a positive correlation with the Sw-RO.

To assess the association with the health scale Sw-NFR and recovery opportunities, participants completed the Sw-RO at the same time as they completed the Sw-NFR. The scales were expected to show a negative correlation.

In order to assess the association with a health scale other than the Sw-NFR, participants completed the Vitality scale from SF-36 [34] at the same time as they completed the Sw-RO. The scales were expected to show a positive correlation.

To assess the association with another health scale the participants completed the single-item version of the Work Ability Index [33] at the same time as they completed the Sw-RO. The scales were expected to show a positive correlation. To assess the association with psychosocial work characteristics the participants completed the Demand subscale from the Demand Control Questionnaire [31] at the same time as they completed the Sw-RO. The scales were expected to show a negative correlation.

Validity of the Swedish Need for Recovery (Sw-NFR) scale

To test the convergent construct validity of the Sw-NFR, the Swedish version of the Vitality scale from SF-36 [34] was included. The participants answered the Vitality scale at the same time as they completed the Sw-NFR. This scale was expected to show a negative correlation with the Sw-NFR. To further test the convergent construct validity of the Sw-NFR, participants answered the singleitem version of the Work Ability Index [33] at the same time as they completed the Sw-NFR. This scale was expected to have a negative correlation with the Sw-NFR.

To assess the association with psychosocial work characteristics participants answered the Demand subscale from the Demand Control Questionnaire [31] at the same time as they completed the Sw-NFR. The scales were expected to have a positive correlation. To further assess the association with psychosocial work characteristics participants completed the Control scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire [31] at the same time as they completed the Sw-NFR. This scale was expected to have a negative correlation with the Sw-NFR.

To further assess the association with psychosocial work characteristics participants completed the Swedish version of the control scales Influence at Work and Possibilities for Development from the COPSOQ [32] at the same time as they completed the Sw- NFR. These scales were expected to show a negative correlation with the Sw-NFR.

Reliability

Reliability may be accessed through internal consistency and stability. To assess internal consistency of the Sw-RO, all the participants (n=142) who had participated in the validity tests were included in the analysis. This was also the case for the assessment of internal consistency of the Sw-NFR. For the participants who had answered the scales twice (n=84) for the stability test, the first score was included in the analysis of internal consistency. Cronbach's alpha was used to assess internal consistency of both Sw-RO and Sw-NFR. Terwee [35] propose a criterion of 0.70 and 0. 95 as a measure of good internal consistency.

The stability of the Sw-RO and Sw-NFR was assessed in a subgroup of 84 workers who completed the questionnaires twice. The interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to verify the stability of both of the scales in the test and retest. It has been proposed that the reliability can be positively rated when the ICC is at least 0.70 in a sample size of at least 50 patients [35].

Factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation was performed regarding both scales. An Eigenvalue greater than one was used to determine number of factors.

Ethics

All participants were informed about the aim of the study and signed a consent form. The research proposal was approved by the Gothenburg board of ethics: Dnr 139-14.

Result

Cross-cultural adaptation process

The translation and back translation processes were relatively straightforward. The expert review committee found a few minor discrepancies between the original version and the translation. Each discrepancy was discussed by the expert committee, and the most adequate wording was chosen. In addition, the word order was discussed for some items. The level of formality was discussed for some words; for example, the term "arranged" in item 7 in the Sw-RO was discussed, as the first word used was more formal and was consequently replaced with a more common word. In the Sw- NFR the term "evening meal", in item 4, was discussed from an experiential equivalence perspective. The expert committee agreed on the Swedish term "kvaUsmat” which translates as evening meal. Because of the change from dichotomous to four-point frequency- related answer categories, any words that denoted frequency was removed from the following items in Sw-NFR: 4, 5, 8, 10, 11.

During pretesting, some participants had problems answering item 6 in the Sw-RO, Can you be obliged to work on a holiday day? A number of participants (administrative staff) explained that their employers probably had the legal right to require them to work on a holiday day, but that this never happened in reality. Because of this, the item was changed to Does it happen that you have to work on a holiday day? The new version of the item was then tested with 15 participants with no further issues. The final Sw-Ro and Sw-NFR were proposed on the basis of the results from the pretesting.

Psychometric properties

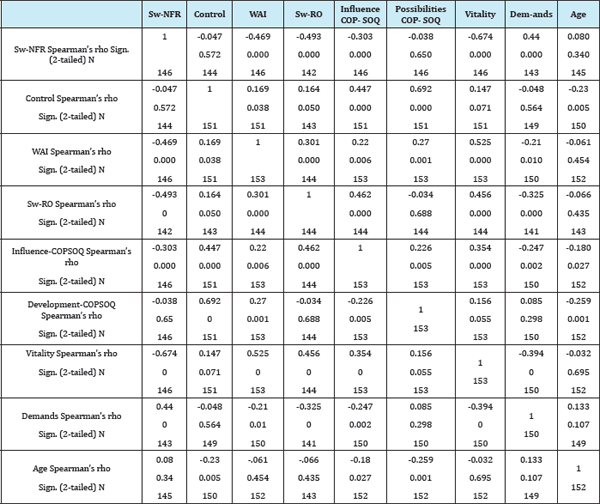

Construct validity of the Sw-RO: (Table 1) presents the means and correlations for all the study variables. As can be seen in Table 1,

Table 1: Means and correlations for all study variables in terms of Need for recovery after work (Sw-NFR) and Recovery Opportunities related to work shifts (Sw-RO). Job demands and Control were measured by the Demand subscale (Demand Control Questionnaire). Control was further recorded by Influence at Work scale and 'Possibilities for Development scale' from Copenhagen Psycho Social Questionnaire (COPSOQ). The health scales were the Vitality scale from SF-36 and the single item Work Ability Index.

Sw- NFR- Need for Recovery scale (Swedish version), WAI- Work Ability Index; Sw-RO- Recovery Opportunities scale (Swedish version); COPSOQ- Copenhagen Psycho Social Questionnaire.

A. A significant positive correlation was found between Sw-RO score and the Influence at Work control scale from the COPSOQ (p<0.001), with a medium level of correlation (r=0.46).

B. A nonsignificant negative correlation was found between Sw-RO the Possibilities for Development control scale from the COPSOQ (p>0.05), with a low level of correlation (r=-0.03).

C. A significant negative correlation was found between Sw-RO score and the Demand scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire (p<0.001), with a medium level of correlation (r=-0.33).

D. A significant correlation was found between Sw-RO score and the Control scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire (p<0.001), with a low level of correlation (r=0.16).

E. A significant negative correlation was found between Sw- RO score and the Sw-NFR scale (p<0.001), with a medium level of correlation (r=-0.49).

F. A significant positive correlation was found between Sw- RO score and the Vitality scale (p<0.001), with a medium level of correlation (r=0.46).

G. A significant positive correlation was found between Sw- RO score and the single-item version of the Work Ability Index (p<0.001), with a medium level of correlation (r=0.30).

Construct validity of the Sw-NFR

As can be seen in Table 1, a significant negative correlation was found between Sw-NFR score and the Vitality scale from SF-36 (p<0.001), (r=0.674): the convergent validity was good.

A. A significant negative correlation was found between Sw- NFR score and the single-item version of the WAI (p<0.001), (r=- 0. 47): the convergent validity found was moderate.

B. A significant negative correlation was found between Sw- NFR score and the Sw-RO scale (p<0.001), (r=-0.49): the convergent validity found was moderate.

C. A significant positive correlation was found between Sw-NFR score and the Demand scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire (p<0.001), with a medium level of correlation (r=0.44).

D. A not significant negative correlation was found between Sw-NFR score and the Control scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire (p>0.05), with a low level of correlation (r=-0.05).

E. A significant negative correlation was found between Sw- NFR score and the Influence at Work control scale from the COPSOQ (p<0.000), with a medium level of correlation (r=-0.30).

F. A not significant correlation was found between Sw-NFR score and the Possibilities for Development scale from the COPSOQ. (p>0.05), with a low level of correlation (r=-0.04).

Stability test-retest

Good stability for the test-retest scores was found for the Sw- RO (ICC=0909.x, p<0.001) among 84 participants. Similarly, good stability was found for the Sw-NFR (ICC=0.911, p<0.001) among 84 participants.

Internal consistency

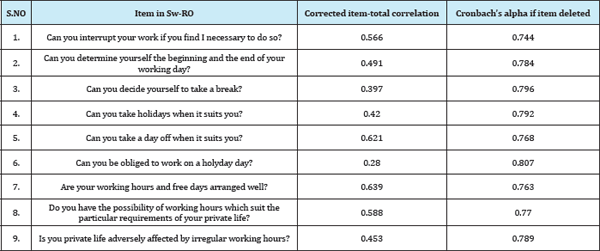

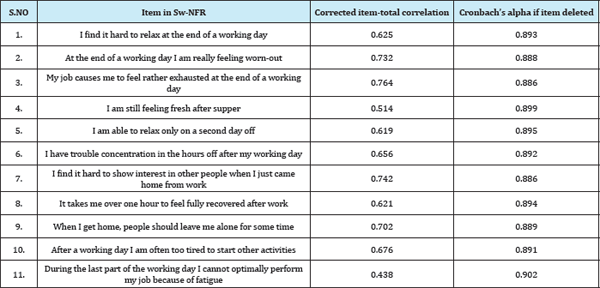

Good internal consistency was found for the Sw-RO (Cronbach's alpha=0.803) among 142 participants, considering all 9 items. Similarly, good internal consistency was found for the Sw-NFR (Cronbach's alpha=0.901) among 146 participants, considering all 11 items. The split half reliability for the Sw-RO was 0.651, and for the Sw-NFR it was 0.892. In Tables 2 & 3 the items-total correlation and alpha-if-item-deleted are reported for each of the items on the Sw-RO and Sw-NFR.

Table 2: Results of corrected item-total correlation and Cronbach's alpha if items deleted one at a time from the scale Recovery Opportunities (Sw-RO) related to work shifts.

Sw-RO- Recovery Opportunities scale (Swedish version).

Table 3: Results of corrected item-total correlation and Cronbach's alpha if items deleted one at a time from the scale of Need for recovery (Sw-NFR) after work.

Sw-NFR, Need for Recovery scale (Swedish version)

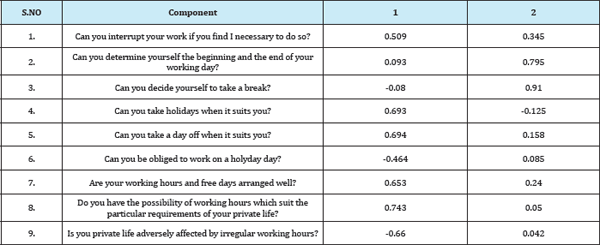

Principal Component Analysis Sw-RO

An exploratory Principal Component Analysis was performed with Sw-RO. The measure of sampling adequacy (Bartlett s statistic) was significant (χ2=355,186, df=36, p<0.001) with Kaiser-Meyer- Olkin index at 0.80. These measures indicated that the data was appropriate for factor analysis [34]. The exploratory factor analysis showed that two factors emerged with an Eigenvalue greater than 1. Results of the scree plot suggested this is in accordance with two factors were 53% of the variance explained by the two factors. Factor 1 could be defined by items concerning influence regarding the interface between life outside work, e.g. taking a day off or the work shifts being well scheduled from the perspective of recovery.

One item covering influence over the internal recovery of taking breaks during work also loaded on factor 1. Factor 2 could be defined by mainly two items concerning influence over daily hours of work and breaks during these hours. The item concerning actual scheduling of shifts from the perspective of recovery, the item of influence over taking a day off and the item concerning influence over breaks loaded on both factors but with an overweight on factor 1. See Table 4 for factor loadings for all items in Sw-RO.

Table 4: The scale Recovery Opportunities (Sw-RO) related to work shifts. A two-factor solution after Oblimin rotation with Kaiser Normalization.

Principal Component Analysis Sw-NFR

An exploratory Principal Component Analysis was performed with Sw-NFR. The measure of sampling adequacy (Bartlett's statistic) was significant (χ2=769,32, df=55, p <0.001) with Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin index at 0.92. These measures indicated that the data was appropriate for factor analysis [36]. The exploratory factor analysis showed that one factor emerged with an Eigenvalue greater than 1. Results of the screed plot suggested this is essentially in accordance with one factor were 52% of the variance explained by this first and single factor. In terms of loadings, a homogeneous group of items ranged from .692-.897. The highest loadings belonged to items concerning exhaustion and lack of interest in other people after the shift with. An item concerning fatigue during the last hours of the work day had a loading of .51.See Table 5 for factor loadings for all items in Sw-RO.

Table 5: The scale of Need for recovery (Sw-NFR) after work. A one-factor solution after Oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization.

Discussion

A cultural adaptation of the RO and NFR was made and both measures showed good stability, internal consistency, and expected construct validity. Regarding the construct validity, a significant positive low-level correlation was found between Sw-RO score and the Swedish version of the control scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire. There was a positive medium-sized correlation between the Sw-RO and the Swedish version of the Influence at Work scale from the COPSOQ. This result is in accordance with van Veldhoven [16], who found significant medium-sized correlations between decision latitude and recovery opportunities in three large samples. They argued that the two different manifestations of control at work in reality play separate roles concerning the impact of psychosocial job demands on individual's health. Thereby, correlation between qualities of decision latitude and recovery opportunities should not be so high as to make a fact of control over breaks, work hours, and holidays redundant.

The separate role played by recovery opportunities is supported by a study by Kiss [7], examining COPSOQ I and COPSOQ II scales and the prediction of NFR scores. The researchers found that control over, for example, short breaks and holidays was the only "control" factor that significantly predicted NFR. In parallel, the Sw-RO was the "control" work characteristic that had by far the strongest correlative association with the Sw-NFR. The demand scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire showed the second strongest correlative association with the Sw-NFR. The present result showing an association between the Karasek-Theorell demand scale but not the control scale with a health measure was also reported from a Swedish study on the stress-energy model [37] suggesting an importance role for control over detachment "breaks" for health.

Nonsignificant/low correlations were found between the COPSOQ Possibilities for Development scale and the Sw-RO, and the correlation between Sw-RO score and the Swedish version of the control scale from the Demand Control Questionnaire was low. From the perspective of face and expected construct validity this seems right. The items of the Sw-RO concern the personal sphere and personal needs and their interface with the work shifts. In this respect the Karasek-Theorell [31] control scale and the COPSOQ Possibilities for Development scale both work almost in the opposite direction, since they record the focus on current work tasks and skills development in relation to these and future tasks. This focus or orientation of the control span towards work tasks carries a potential risk of narrowing attention towards work to such a degree that it fosters mental absorption by the work tasks.

From a more theoretical point of view Allen [38] discussed absorption on the basis of detachment. In the words of Allen [38] the effect from absorption on detachment ranges from a mild and normal level to the extreme, and "to be absorbed in one domain is to be detached from others. Thus focused attention entails a balance between absorption-engagement and detachment-disengagement.” Regarding recovery from work recent findings on the role of attachment to the personal sphere allowed by detachment from work seem relevant and detachment from work as a prerequisite for successful recovery is stressed by e.g. Sonnentag [17]. Geurtz [39] discussed the role of control in the work situation from the perspective of making way for mini-breaks thereby avoiding, e.g. strain injuries. An important role of control in job design could be protection against 'invasive' absorption while producing micro detachment (mental mini-breaks) from work, in turn making way for detachment from work after the shifts. Therefore, recovery opportunities may counteract absorption by allowing ongoing "healthy” switches between attachment and detachment thus ensuring attachment to the personal space. A "detachment”- promoting role of being able to control the personal space of, for example, breaks was also suggested by Kiss [7]. This need to prevent absorption from work tasks is also underlined by the fact that stress in itself is known to narrow attention [40] thereby linking with absorption and potentially making detachment from work more difficult.

Through principal component analysis, the RO instrument was mirrored by two factors. The first and largest of these factors is usually the most informative by comprising the largest proportion of the total variance. Regarding RO the first factor could be said to mirror degrees of freedom in life regarding recovery. Although parallel the factors were not entirely separable into two different theoretical constructs. The two factor model with in fact three out of nine items (with loadings≥.3) common to both factors raises questions if a more general phenomenon of recovery from work load is captured by both factors together in terms of covering and quantifying aspects of the personal life space that theoretically allows detachment from work thereby facilitating recovery from work demands. In contrast the single principal component of NFR instead shows work related fatigue which is an outcome measure in part resulting from the interplay between work demands and resources to meet these demands. A relationship between NFR and the resource measure of RO is also shown by a medium level correlation.

The Sw-NFR was found to be a reliable instrument for the sample studied. It met with the criteria for adequate internal consistency and stability. This is in line with previous studies that have found that Cronbach’s alpha and the ICC of the NFR scale are good [25]. Regarding the construct validity, there was a strong correlation between the Sw-NFR and the Swedish version of the Vitality scale from SF-36. This indicates that these scales are measuring similar but not identical concepts. Moriguchi [27] and van Veldhoven [3] have suggested that SF-36 could be more sensitive, measuring chronic fatigue, whereas the NFR is a shorter-term fatigue measure. The corrected item-total correlation score for the Sw-NFR indicated that question 7, I cannot really show any interest in other people when I have just come home myself, had the highest correlation with the rest of the scale. Thus, this question appears to capture the notion of need for recovery.

Interest is part of positive affect and a growing body of research suggests that positive affect could play an important part in psychological and physical well-being [41]. Moreover, detachment from work and shifting attention to something else is very important in the recovery process. "Something else” also plays an important role in down regulating the physiological stress response [42]. Question 11, A feeling of tiredness prevents me from doing my work as well as I normally would during the last part of the working day, had the lowest level of correlation with the rest of the scale. This phenomenon may correspond to an observation by Aronsson [14] on employees protecting their performance in spite of being insufficiently recovered.

Conclusion

Both the Sw-RO and the Sw-NFR showed effective qualities with good stability, internal consistency, and expected construct validity. The instruments confirmed findings from other countries regarding correlations with well-established instruments including the meaning of work demands for both measurements. The meaning of the control scale RO value for the NFR value supports suggestions that detachment from work is important for recovery and health.

References

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ (2006) Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer- term outcomes. Arch Intern Med 166(21): 2314-2321.

- Mahdizadeh M, Heydari A, Moonaghi HK (2015) Clinical Interdisciplinary Collaboration Models and Frameworks From Similarities to Differences: A Systematic Review. Glob J Health Sci 7(6): 170-180.

- Rodgers BL (2000) Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In: Rodgers BL, Knafl KA (Eds.), Concept Development in Nursing: foundations, techniques and applications. (2nd edn), pp. 87-103.

- Cambridge Dictionary (2017) Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Klein JT (2014) Communication and collaboration in interdisciplinary research. In: Rourke MO, Crowley S, Eigenbrode SD, Wulfhorst (Eds.), Enhancing Communication & Collaboration in Interdisciplinary Research. SAGE Publications, New York, USA.

- Harper D (2017) Online Etymoglogy Dictionary.

- Baggs JG, Schmitt MH (1988) Collaboration between nurses and physicians. Image Journal of Nursing Scholarship 20(3): 145-149.

- Andvig E, Syse J, Severinsson E (2014) Interprofessional collaboration in the mental health services in norway. Nursing Research and Practice 2014(2014): 1-8.

- Korner M (2010) Interprofessional teamwork in medical rehabilitation: a comparison of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team approach. Clin Rehabil 24(8): 745-755.

- Korner M, Lippenberger C, Becker S, Reichler L, Muller C, et al. (2016) Knowledge integration, teamwork and performance in health care. J Health Organ Manag 30(2): 227-243.

- Maddock A (2014) Consensus or contention: an exploration of multidisciplinary team functioning in an Irish mental health context. European Journal of Social Work 18(2): 246-261.

- Mulvale G, Bourgeault IL (2007) Finding the Right Mix: How Do Contextual Factors Affect Collaborative Mental Health Care in Ontario? Canadian Public Policy 22: S49-S64.

- Mulvale G, Bourgeault IL (2007) How Do Contextual Factors Affect Collaborative Mental Health Care in Ontario. Canadian Public Policy 33(Suppl 1): S49-S64.

- Sommerseth R, Dysvik E (2008) Health professionals' experiences of person-centered collaboration in mental health care. Patient Prefer Adherence 2: 259-269.

- Nancarrow SA, Booth A, Ariss S, Smith T, Enderby P, et al. (2013) Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Hum Resour Health 11: 19.

- Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, Mc Nellis B, Okun S, et al. (2012) Core Principles & Values of Effective team-based health care. Institute of Medicine, Washington DC, USA.

- Alavi M, Irajpour A, Abdoli S, Saberizafarghandi MB (2012) Clients as mediators of interprofessional collaboration in mental health services in Iran. J Interprof Care 26(1): 36-42.

- Albro TJ (2011) Interdisciplinary collaboration in a psychiatric treatment setting : a project based upon an investigation at Bradley Hospital, Riverside, Rhode Island.

- Allen DE, Nesnera A, Souther JW (2009) Executive-Level Reviews of Seclusion and Restraint Promote Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Innovation. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 15(4): 260-264.

- Auliffe CM (2009) Experiences of Social Workers within an Interdisciplinary Team in the Intellectual Disability Sector. Critical Social Thinking: Policy and Practice 1: 125-143.

- Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF (2013) Multiple perspectives on shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare. J Interprof Care 27(3): 223-230.

- Kaba A, Wishart I, Fraser K, Coderre S, Mc Laughlin, et al. (2016) Are we at risk of groupthink in our approach to teamwork interventions in health care? Med Educ 50(4): 400-408.

- Sunderji N, Waddell A, Gupta M, Soklaridis S, Steinberg R (2016) An expert consensus on core competencies in integrated care for psychiatrists. General Hospital Psychiatry 41: 45-52.

- Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF (2013) Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: a qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J Interprof Care 27(5): 373-379.

- Bailey D (2010) Interdisciplnary working in mental health. New York.

- Blomqvist S, Engstrom I (2012) Interprofessional psychiatric teams: is multidimensionality evident in treatment conferences? J Interprof Care 26(4): 289-296.

- Bookey BS, Markle RM, Mc Key, Akhtar DN (2017) Understanding interprofessional collaboration in the context of chronic disease management for older adults living in communities: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 73(1): 71-84.

- Bruner P, Waite R, Davey MP (2011) Providers' perspectives on collaboration. Int J Integr Care 11: e123.

- Deber R, Baumann A (2005) Barriers and facilitators to enhancing interdiscplinary collaboration in primary health care. The Conference Board of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

- Desplenter FA, Laekeman GM, Simoens SR (2009) Pathway for inpatients with depressive episode in Flemish psychiatric hospitals: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst 3(1): 23.

- Tofthagen R, Fagerstrom LM (2010) Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis--a valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scand J Caring Sci 24(Suppl 1): 21-31.

- Tomizawa R, Yamano M, Osako M, Misawa T, Reeves S, et al. (2014) The development and validation of an interprofessional scale to assess teamwork in mental health settings. J Interprof Care 28(5): 485-486.

- Eisenberg L, Guttmacher LB (2010) Were we all asleep at the switch? A personal reminiscence of psychiatry from 1940 to 2010. Acta Psychiatr Scand122(2): 89-102.

- Ghesquiere AR, Pinto RM, Rahman R, Spector AY (2015) Factors Associated with Providers' Perceptions of Mental Health Care in Santa Luzia's Family Health Strategy, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(1): ijerph13010033.

- Walker LO, Avant KC (2005) Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. (4th edn), USA.

- Schroder C, Medves J, Paterson M, Byrnes V, Kelly C, et al. (2011) Development and pilot testing of the collaborative practice assessment tool. J Interprof Care 25(3): 189-195.

- Pollard KC, Miers ME, Gilchrist M (2004) Collaborative learning for collaborative working? Initial findings from a longitudinal study of health and social care students. Health Soc Care Community 12(4): 346358.

- Novella EJ (2010) Mental health care and the politics of inclusion: a social systems account of psychiatric deinstitutionalization. Theor Med Bioeth 31(6): 411-427.

- Haggarty JM, Rayan NKD, Jarva JA (2010) Mental health collaborative care: a synopsis of the Rural and Isolated Toolkit. Rural Remote Health 10(3): 1-10.

- Irajpour A, Alavi M, Abdoli S, Saberizafarghandi MB (2012) Challenges of interprofessional collaboration in Iranian mental health services: A qualitative investigation. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 17(2 Suppl 1): S171- 177.

- Lee E, Kealy D (2014) Revisiting Balint's innovation: enhancing capacity in collaborative mental health care. J Interprof Care 28(5): 466-470.

- Corcle M (1982) Critical issues in the functioning of interdisciplinary groups. Small Group Behavior 13(3): 291-310.

- Kenna MH (2000) Nursing Theories and Models.

- Miller CJ, Grogan KA, Perron BE, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS, et al. (2013) Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and metaregression to guide future research and implementation. Medical Care 51(10): 922-930.

- Petri L (2010) Concept analysis of interdisciplinary collaboration. Nurs Forum 45(2): 73-82.

- Sfetcu R (2013) Collaboration practices in mental health care: multidisciplinary teamwork or inder-professional collaboration groups? Mangement in Health 7(2):

- Voort TY, Meijel B, Goossens PJ, Hoogendoorn AW, Draisma S, et al. (2015) Collaborative care for patients with bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 206(5): 393-400.

- Rensburg AJ, Fourie P (2016) Health policy and integrated mental health care in the SADC region: strategic clarification using the Rainbow Model. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 10: 49.

- Wormer A, Lindquist R, Robiner W, Finkelstein S (2012) Interdisciplinary collaboration applied to clinical research: an example of remote monitoring in lung transplantation. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 31(3): 202210.

© 2017 Kerstin Wentz, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)