- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

A Concept Analysis of Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Mental Healthcare

Lam AHY1*, Jacky Tsz Lung Wong2, Eris Ching Man Ho3, Rita Yik Yan Choi4 and Matthew Shing Tack Fung5

1School of Nursing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2Tung Wah College, Hong Kong

3Department of Occupational Therapy, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

4Occupational Therapy Department, North District Hospital, Hong Kong

5Department of Clinical Pathology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

*Corresponding author: Angie Ho Yan Lam, School of Nursing, The University of Hong Kong, 4/F, William MW Mong Block, 21 Sassoon Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, Tel: 3917 6975; Email: angielam@hku.hk

Submission: August 29, 2017; Published: November 29, 2017

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume1 Issue2

Introduction

Given the complexity of bio-psycho-social-spiritual influences, people with mental illness should be provided with multifaceted treatment and multi-system intervention. Mental health care teams are therefore expected to achieve interdisciplinary collaboration (IDC) to ensure delivery of safe, high-quality and well coordinated health care. There is increasing evidence to suggest that IDC leads to better patient outcomes. A growing body of research has shown that IDC is more effective than standard care in terms of clinical outcomes such as improved quality of life and alleviated depressed mood in people with mental disorders-with reducing healthcare costs [1]. Despite advances in research, there is still a lack of conceptual clarity of IDC, resulting in inconsistent models of care and inconsistent findings [2]. The ambiguous conceptualization of IDC impedes the standardisation of evidence-based practice and also limits practical applicability and comparability. Thorough understanding of the meaning of IDC in the context of mental healthcare is of vital importance in guiding further studies and evidence-based practice.

Background (Rogerians's Evolutionary Concept Analysis)

Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis is an inductive approach to 'clarify the concept and its current use, and uncover the attributes of the concept as a basis for further development' [3]. Rodgers maintained that concepts develop over time and was influenced by context [3]. While IDC in mental healthcare has been developing and improving over the last decade, Rodgers’ [3] evolutionary concept analysis is regarded as an appropriate method to identify the elements of IDC in the context of mental healthcare. It is also instrumental in distinguishing the concept from a multitude of related terms, gaining understanding of the conceptualization of IDC, and providing a direction for further research and translation of the concept into practice. This article aims to illustrate the concept of IDC in the context of mental healthcare for development of an effective work model.

Methods

Rodgers' [3] methods include

a) Identifying the concept of interest and its associated expressions;

b) Identifying and selectingan appropriate sources (setting and sample) for data collection;

c) Analysing relevant data to identify the contextual basis of the concept, including antecedents, attributes, consequences, and interdisciplinary variations;

d) Analysing data regarding the above characteristics of the concept;

e) Identifying an exemplar of the concept; and

f) Identifying implications and hypotheses for further development.

Data Selection

Rodgers [3] recommended obtaining at least 30 publications from relevant disciplines, or 20% of the total population. This analysis selected published literature in English. Systematic searches were made of the electronic databases MEDLINE, PubMed, CLINAHL, PsycINFO. Meanwhile manual searches were conducted on Google Scholar, university libraries and reference lists to identify any relevant papers. The search period was set as 20072017 to gain an understanding of the current meaning. The terms for keyword search included interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interprofessional*, collaborat*, cooperat*, team*, and, working. The relevance of the literature was assessed for inclusion based on the following criteria: whether the literature

a) Is instrumental in clarifying the concept, contributing to the definition, and/or identifying the antecedents , attributes, consequences and evolution of interdisciplinary collaboration;

b) Is a related qualitative or quantitative research,conceptual article, systematic review, or a book concerning IDC inmental healthcare realms;

c) Covers two or more disciplines

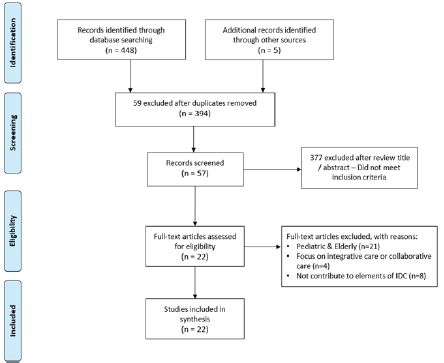

d) Is related to mental health care for adults aged 16-65. Articles not specific to the context of healthcare or patient care were excluded. Twenty percent of the articles obtained from each database were selected using a random sampling technique. A total of 22 documents were finally retained for analysis, including primary research and conceptual theoretical papers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Study flow diagram.

Data Collection, Management and Analysis

The database search identified all potentially relevant studies based on the information contained in the title, abstract and descriptor/MeSH headings. The studies were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria to confirm eligibility for inclusion. Each literature, after retrieval, was read multiple times to obtain the essence of the contents, and to systematically extract relevant data to identify the contextual basis of the concept according to Rodgers' [3] pre-determined model criteria. The authors of this paper developed an electronic data extraction sheet. Key terms and phrases were set for running the frequency counts. The terms of frequent occurrence were divided into categories based on the prevalent theme, i.e. attributes, antecedents, consequences. Surrogate and related terms were also tallied and compared with the definitions of interdisciplinary collaboration. Charts and tables were designed to present the findings in a clear manner.

Findings

Common definitions and uses

'Interdisciplinary' is defined as 'involving two or more different subjects or areas of knowledge’ [4]. McCorcle brought forward the idea that 'interdisciplinary' operates in a more complex environment, such as an open system that has a heterogeneous though interconnected membership. Klein [5] defined 'interdisciplinary' as 'integrating information, data, methods, tools, concepts, or theories from two or more disciplines or bodies of knowledge to address a complex question, problem, topic, or theme’ [5].

According to Cambridge Dictionary,' collaboration’means 'the situation of two or more people working together to create or achieve the same thing [4]. 'Collaboration' originated from Late Latin in the period 1870-1875, with a meaning 'to cooperate, usually willingly, with an enemy nation, especially with an enemy occupying one’s country’ [6]. In the late 1980s, Baggs & Schmitt [7] studied collaboration in the healthcare field and defined collaboration as 'cooperatively working together, sharing responsibility for solving problems, and making decisions to formulate and carry out plans for patient care' [7].

Attributes

Attributes are clusters of characteristics that constitute the true meaning of a concept [3]. The following attributes of the concept IDC were identified in reviewing the literature:

A. Understanding roles and knowledge across all disciplines,

B. communication,

C. respect,

D. share decision making,

E. share goal.

Understanding roles and knowledge across all disciplines

Understanding different discipline-specific roles and knowledge cultivates a culture of collaboration [8-14]. Members of different disciplines are equipped with specific knowledge and competencies within their own discipline [8]. Members across different disciplines also have their own understanding of common terminologies, patients' overall health and recovery process [8]. Shared understanding capitaliseson the strengths of each discipline for the clients’ ultimate benefit. Through understanding each discipline's professional functions, practice styles, responsibilities and accountability system, the team can effectively identify member's strengths, limitations, boundaries and potential impacts on clients [15]. Team members also develop clear expectation for each teammate in making appropriate contribution and achieving division of labour across disciplines [16]. In addition, teammates must have shared understanding of relevant knowledge of their tasks, including the aim, work process, ways of working, methods and tools [10]. Such knowledge ensures everyone knows what to do, how to do, who should do, with whom to do and what for [16].

Communication

The most common attribute of IDC in the context of mental healthcare was communication [17-23]. Open communication facilitates shared understanding which can ensure each discipline's perspectives are regarded, for the clients’ benefits [20]. Open communication also facilitates role negotiation and information sharing [24]. Communication among team members may encompass formal and informal means ranging from team meeting, case conference, joint professional discussion, and use of information technology such as electronic health records, emails and teleconferencing [24]. Such means provide effective communication channels between team members and enhance the accessibility of clients' health information. Open communication was also one of the essential ways to develop other attributes including respect, share decision making and share goal [20].

Respect

Effective IDC lies on team members’ mutual respect [25-30]. It is fundamental to build a collaborative, supportive environment and mutually trusting relationships with other providers [23]. Team members should recognise and respect each other’s roles, values, practices, professional culture and judgment so as to create relational collaboration [12,13]. More importantly, they should fairly regard and evaluate the contributions by each discipline [8]. Each team member is encouraged to utilize their own skills for the best outcomes under the atmosphere of mutual trust and respect [23]. Respect is also essential to develop role interdependence in which teammates can rely on and complement each other, with different competencies, while acknowledging individual roles and autonomy [23]. Mutual respect may develop from other attributes such as understanding roles and enhancing communication.

Share decision making

Share decision making is an important attribute to achieve effective IDC [8-14]. Shared decision making is a collaborative process in which healthcare professionals make health related decisions together with the clients. Through the process, both the healthcare providers and the clients (and their family) contribute valuable information for decision making [24]. Share decision making ensures the perspectives of all disciplines are considered during the planning process so that clients' benefits can be maximized [22]. Active involvement of clients and their family allow their day-to-day concerns and needs are regarded in developing the healthcare choices and goals, arriving at mutual agreement [21]. Share decision making also facilitates empowerment for clients, enhancing their satisfaction towards the healthcare system and improving their self-management of illness [21].

Share goal

Share goal is an attribute that can foster IDC [17-30]. Shared goal can drive the whole team to make endeavours for a common goal that cannot be reached when individuals work on their own [17]. In IDC, each team member may contribute to conclude a collective goal-among discipline-specific goals-through negotiation [10]. Teammates should work towards the common goal by utilizing and integrating their own expertise, skills and knowledge. Interdisciplinary teams show better clients’ outcomes with the common goal while the teammates can overcome their differences to accomplish clients’ needs collectively [12].

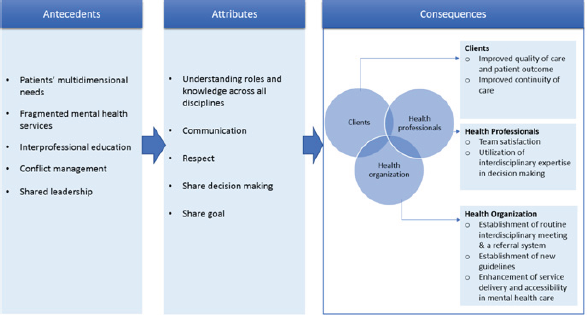

Antecedents

Rogers defined antecedents as the events or phenomena that have to be present prior to the existence of a concept [31]. In the context of mental healthcare, the antecedents for the concept IDC include patients’ multidimensional needs, fragmented mental health services, inter professional education, conflict management and shared leadership (Figure 2).

Patients' multidimensional needs

Mental illness is a brain-based problem with complex, multifaceted constructs in relation to genetic, neurological, environment, and interpersonal factors [25]. People with mental illness have various needs along their developmental lifespan in view of physical problems, psychological burden, family issues, finance, housing and other socio-emotional factors [20]. With the multi-faceted nature, the needs of these clients are extensive and multidimensional [12-17]. These complex needs should be addressed with multidimensional interventions delivered by health professionals with diverse knowledge and skills [20]. With IDC, health professionals with different expertise and skills are able to take care of the clients with a holistic approach [17].

Figure 2: Conceptualization of IDC in the context of mental healthcare.

Fragmented mental health services

The fragmentation of health care services constitutes a challenge to the collaboration process [9-17]. The decentralised and fragmented nature of health care systems brings about communication gaps and obstructs shared decision-making between health providers, affecting the continuity of care [21]. Both healthcare providers and clients in the fragmented healthcare services express dissatisfaction and frustration springing from the fact that they are not able to work collaboratively in improving the care [21]. The fragmentation calls for effective collaboration among healthcare professionals of different disciplines which leads to integration and continuity of care [10].

Interprofessional education

Education related specifically to IDC is the most common antecedent of the concept [18,24-26]. Interprofessional education can enhance interdisciplinary practice and care delivery by fostering collaborative attitude and core competencies of collaborative practice [11]. Through an interactive collaborative learning environment, team members of different disciplines learn with and from each other. Interprofessional education facilitates team members to gain an insight into the roles of different disciplines and such learning process can promote mutual understanding and mutual respect-an attribute of IDC [11,18]. Interprofessional education also invites exploration of possible clinical conflicts from various professional and cultural perspectives [18]. There have been opinions that interdisciplinary education should beintegrated into the relevant undergraduate programmes and post-graduate mental health training so as to promote IDC [24].

Conflict management

Role ambiguity, overlapping responsibilities and interdisciplinary conflicts are constant problems in IDC [18,25-32]. Overlapping scopes of practice tend to occur when there is a shared body of knowledge amongst disciplines [17]. Such overlap muddles the role boundaries and the team members' responsibilities, especially when there are unclear regulations and policies in a health system [18,20]. Interdisciplinary conflicts led to tension and friction between disciplines, resulting in weak team functioning, low team effectiveness, and inferior patient care [32]. Effective conflict management can minimise the negative impacts brought by the aforesaid problems and at the same time promote other attributes of IDC, for example, understanding roles and knowledge across disciplines and promoting mutual respect [17].

Shared leadership

Leadership establishes the foundation of IDC, with continuous teamwork towards common goals [18-23]. Shared leadership is conducive to IDC: Assigned respective leadership responsibilities, different disciplines can jointly implement practices and institute changes through negotiation, rather than simply following 'orders' as in the conventional model [23]. Shared leadership not only allows the team to benefit from making use of each member’s (each discipline’s) expertise, but also avoids intrusion of hierarchy, and inequalities in powers or status conferred to the team members.

Consequences

According to Rodgers BL [3], consequences are the results from the occurrence of a concept. The consequences identified for IDC in this context are positive in nature. Favourable outcomes are seen for clients, organisations, and healthcare professionals.

Health Organization

Establishment of routine interdisciplinary meetings & a referral system

Establishment of route interdisciplinary meetings and a referral system can promote effective collaboration. The routine meetings should include team members from different disciplines and also clients and their family; through in-depth discussion in the meetings, the healthcare members can gain thorough understanding of clients’ needs while all parties can have insight into the shared goal of care and the details of any integrated plans [8]. IDC meetings provide a regular channel to share ideas, information, and feedback across disciplines for better continuity of care [8]. Establishment of an IDC referral system can enhance collaborative relationships, communication, and the continuity of care [17,20].

Establishment of new guidelines

There has been a need to establish professional guidelines for IDC by which the resources and the activities of the healthcare teams can be regulated [12]. The guidelines can also clearly define the scopes of professional practices, the practice standards, and the accountability of the team so that the team members can get well aware of their role and responsibilities in IDC [13].

Enhancement of service delivery and accessibility of mental health care

IDC enhances the effectiveness and accessibility of a health care system [12-17]. IDC improves the accessibility of mental health care. With IDC, clients can receive more responsive services, and be guaranteed a safe and seamless transition from a higher level of care to the lower level of care [8].

Health Professionals

Team satisfaction

IDC enhances job satisfaction [11,17]. Through IDC, team members perceive that their effort is recognized and their opinions are valued [19]. IDC also enhances communication among health care staff, clients and clients’ family, which boosts the teamwork [25].

Utilisation of interdisciplinary expertise in decision making

IDC synergizes the expertise of different disciplines to make the best clinical decisions. IDC adopts the notion of 'intellectual synergy' and 'wisdom of crowd’ whereby professionals collaboratively contribute to decision making from different perspectives [26]. It guarantees effective, professional clinical decisions which best matches the clients’ needs, the healthcare staff’s capacities and the resources available in the setting [14].

Clients

Improved quality of care and patient outcome

IDC improves quality of patient care and patient outcomes [823]. IDC exploits the full potientialof different disciplines, resulting in clinical improvement which better benefits the clients [32-34]. It has been seen that IDC brings positive outcomes to mental health care such as improvement in clients’ treatment adherence, quality of life and consumer satisfaction [8]. Successful IDC also improves client empowerment and self-management of illness [21].

Improved continuity of care

Continuity of care is guaranteed in IDC. IDC is a continuous process of coordination among health professionals within and across different levels of care. It is especially important for mentally- ill clients as they are at high risk of experiencing adverse clinical events after discharge [8]. At the same time, IDC can bring out a smooth and seamless transitional discharge in which both the inpatient and community staff can work together for the discharged clients so as to ensure a continuous care in the community [8]. By virtue of IDC, clients receive continuous care from across different disciplines working in a coherent and connected way [29].

Empirical referents

Empirical referents are measurable ways to demonstrate the occurrence of the concept [35]. Only a few instruments have been specifically designed to measure the effectiveness of IDC despite increasing attention to IDC [36]. The University of the West of England Inter professional Questionnaire is a self-report measure to explore attitudes towards collaborative working. The questionnaire comprises four subscales, namely, the communication and teamwork scale, the interprofessional learning scale, the interprofessional interaction scale, and the interprofessional relationship scale [37]. The questionnaire demonstrates high reliability and validity in measuring providers’ communication, teamwork skills, and attitudes towards professional collaboration [37]. Schorder designed the Collaborative Practice Assessment Tool (CPAT) to measure the perceived degree of interprofessional collaboration in healthcare settings. There are 56 items across eight domains:

a. Mission and goals,

b. Relationships,

c. Team leadership,

d. Role responsibilities and autonomy,

e. Communication and information exchange,

f. Community linkage and coordination,

g. Decision-making and conflict management, and

h. Patient involvement [36].

In addition, there are three open-ended questions for comment on the team’s strengths in collaborative practice, challenges and the assistance needed for achieving improvement [36]. The results of two pilot tests suggested CPAT had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.7-0.9) and excellent model fit (Normed Fit Index & Comparative Fit Index >0.9 for all domains [36]. Nevertheless, these measurements only assessed the effectiveness of IDC in general healthcare setting but not specifically in mental healthcare.

Surrogate and Related Terms

A multitude of articles used surrogate and related terms in expressing the concept of IDC. Interprofessional collaboration and interprofessional teamwork have been used interchangeably in the context of mental healthcare. Meanwhile, interprofessional collaboration is defined as 'the process of developing and maintaining effective interprofessional working relationships with learners, practitioners, patients/clients/families and communities to enable optimal health outcomes' [32]. Ghesquiere [34] also used transdisciplinary collaboration as an interchangeable term for IDC. Transdisciplinary collaboration is 'characterised by providers working together to incorporate various types of knowledge, and identifying solutions by transcending disciplinary perspectives’ [34].

Related terms (of IDC) include multidisciplinary team and multidisciplinary teamwork. The main difference between IDC and the concept of 'multidisciplinary team’ is out of the collective collaboration approach in IDC. In defining multidisciplinary teamwork, Korner [9] stated 'the different disciplines work separately, each with its own treatment goals. The physician determines and delegates the treatment options to the other health care professionals in a one-way, mostly bilateral interaction process between the professionals’ [8] Whereas, in IDC, team members have a shared discipline to work collectively towards a shared goal. This collective goal is agreed by consensus according to negotiated priorities [25]. Thus, the IDC model is deemed to have a higher quality of collaboration and team performance [10].

Other related terms include integrated care and collaborative care. Integrated care and collaborative care emphasize on the healthcare treatment approach ranging from parallel care to collaborative networking. The terms also highlight the integrated treatment plans and the multiple-level of mental health service. IDC is believed to be instrumental in improving coordination among health professionals to achieve integrated care or collaborative care.

New Definition/Synthesized Definition

After the elements of IDC were identified in the context of mental healthcare according to Rodgers evolutionary approach (2000), a new definition of the concept emerged: It is an interpersonal process which involves utilising interdisciplinary talents and skills from different healthcare professionals across disciplines, who work together with shared goals and shared decision making to fulfil patients' multidimensional needs and integrate fragmented healthcare services to achieve quality care, best client’s outcome and service delivery. The process is best accomplished with an atmosphere of mutual respect, effective communication, and shared leadership. Health professionals are required to aware and accept one’s roles, knowledge and responsibilities of participating disciplines. Effective IDC would be achieved through interprofessional education, new guidelines, regular meeting, and referral system.

Discussion

The present analysis elaborates the conceptualization of IPC in the context of mental healthcare as shown in Figure 2. It reveals that IDC in this specific realm has the common elements of IDC in the context of general healthcare and chronic diseases [27]. IDC in healthcare is an ongoing interpersonal process which requires mutual understanding, respect and shared decision making among team members towards a common goal [27]. The present analysis also reveals the unique set of characteristics of IDC in the context of mental healthcare, identifying client’s multidimensional needs as one of the unique antecedents in this context which highlights the unique physical, mental and social needs of our clients. Furthermore, this analysis identifies additional antecedents and consequences, noting the evolvement of mental healthcare in recent decades. Deinstitutionalization was introduced after the advent of psychotropic drugs in the 1950s [33]. The introduction of deinstitutionalization caused the mental healthcare to evolve from traditional institutionalisation to community-oriented care, based on the belief that mentally-ill patients would have a higher quality of life and social contribution in the community than being institutionalized [38]. The antecedent 'fragmented mental health services’ and the consequence 'enhancement of accessibility of mental health care’ demonstrate unique characteristics of IDC under the process of deinstitutionalization in mental healthcare.

Earlier definitions of IDC emphasised on the notion of role awareness and the trusty relationship among team members [27]. Our analysis identifies additional components that prevail in the context of mental healthcare: shared leadership, the establishment of new guidelines, routine interdisciplinary meetings and referral system, and enhancement of service delivery and accessibility of mental health care. Extended analysis of the elements of IDC was performed from different perspectives and at different levels- ranging from interpersonal perspectives to structured service coordination across mental healthcare sectors. These elements provide useful information for the establishment of organisational practices. More and more countries tend to study IDC from organisational perspectives, rather than simply considering the linkage across the health professionals within the team [8-10]. In healthcare organisations, formal IDC on one hand helps develop regulatory frameworks and policies at the management level and on the other hand improves the service delivery at the operational level. Consideration should be given to practical factors affecting the implementation of IDC, such as funding and legal issues. Our analysis has also put forward the consequence 'improved continuity of care' in view of the fact that good IDC has ongoing positive impacts on the quality of care [38-44].

Implication

This paper synthesized the currently available literature to analyze the concept IDC, providing insights for improvement of clinical practice and conducting of researches. The analysis brought up an operational model to guide the practice of a mental healthcare setting. Our findings may benefit practitioners in understanding every aspect of IDC so that they can better implement collaborative care [45-48]. In view of the findings, practitioners are encouraged to have review and re-examination on the current practices of IDC in the healthcare settings. Nevertheless, further studies are required to confirm the relations between the antecedents, attributes and consequences of IDC, and to concretize the ways to structure the collaborative practices across members and organisations. This analysis sets the stage for the development of instruments to measure the effect of IDC quantitatively in mental health context. It also encourages the practitioners to identify and gain insight into the facilitators and barriers to the implementation of effective IDC in mental health setting [49].

Conclusion

The aim of this concept analysis is to synthesise the elements of IDC in the context of mental healthcare. It provides a foundation to understand the conceptualization of IDC which is demonstrated to be complex and evolving, with unique characteristics in this specific context. The analysis identified consistent attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the concept which can facilitate the development of further theoretical definitions and effective operational models. The findings are also useful to any applicable future operationalization and development of measures for healthcare practices. Yet further studies are required to maintain ongoing concept development and successful integration of IDC into mental healthcare.

References

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ (2006) Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer- term outcomes. Arch Intern Med 166(21): 2314-2321.

- Mahdizadeh M, Heydari A, Moonaghi HK (2015) Clinical Interdisciplinary Collaboration Models and Frameworks From Similarities to Differences: A Systematic Review. Glob J Health Sci 7(6): 170-180.

- Rodgers BL (2000) Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In: Rodgers BL, Knafl KA (Eds.), Concept Development in Nursing: foundations, techniques and applications. (2nd edn), pp. 87-103.

- Cambridge Dictionary (2017) Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Klein JT (2014) Communication and collaboration in interdisciplinary research. In: Rourke MO, Crowley S, Eigenbrode SD, Wulfhorst (Eds.), Enhancing Communication & Collaboration in Interdisciplinary Research. SAGE Publications, New York, USA.

- Harper D (2017) Online Etymoglogy Dictionary.

- Baggs JG, Schmitt MH (1988) Collaboration between nurses and physicians. Image Journal of Nursing Scholarship 20(3): 145-149.

- Andvig E, Syse J, Severinsson E (2014) Interprofessional collaboration in the mental health services in norway. Nursing Research and Practice 2014(2014): 1-8.

- Korner M (2010) Interprofessional teamwork in medical rehabilitation: a comparison of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team approach. Clin Rehabil 24(8): 745-755.

- Korner M, Lippenberger C, Becker S, Reichler L, Muller C, et al. (2016) Knowledge integration, teamwork and performance in health care. J Health Organ Manag 30(2): 227-243.

- Maddock A (2014) Consensus or contention: an exploration of multidisciplinary team functioning in an Irish mental health context. European Journal of Social Work 18(2): 246-261.

- Mulvale G, Bourgeault IL (2007) Finding the Right Mix: How Do Contextual Factors Affect Collaborative Mental Health Care in Ontario? Canadian Public Policy 22: S49-S64.

- Mulvale G, Bourgeault IL (2007) How Do Contextual Factors Affect Collaborative Mental Health Care in Ontario. Canadian Public Policy 33(Suppl 1): S49-S64.

- Sommerseth R, Dysvik E (2008) Health professionals' experiences of person-centered collaboration in mental health care. Patient Prefer Adherence 2: 259-269.

- Nancarrow SA, Booth A, Ariss S, Smith T, Enderby P, et al. (2013) Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Hum Resour Health 11: 19.

- Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, Mc Nellis B, Okun S, et al. (2012) Core Principles & Values of Effective team-based health care. Institute of Medicine, Washington DC, USA.

- Alavi M, Irajpour A, Abdoli S, Saberizafarghandi MB (2012) Clients as mediators of interprofessional collaboration in mental health services in Iran. J Interprof Care 26(1): 36-42.

- Albro TJ (2011) Interdisciplinary collaboration in a psychiatric treatment setting : a project based upon an investigation at Bradley Hospital, Riverside, Rhode Island.

- Allen DE, Nesnera A, Souther JW (2009) Executive-Level Reviews of Seclusion and Restraint Promote Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Innovation. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 15(4): 260-264.

- Auliffe CM (2009) Experiences of Social Workers within an Interdisciplinary Team in the Intellectual Disability Sector. Critical Social Thinking: Policy and Practice 1: 125-143.

- Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF (2013) Multiple perspectives on shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare. J Interprof Care 27(3): 223-230.

- Kaba A, Wishart I, Fraser K, Coderre S, Mc Laughlin, et al. (2016) Are we at risk of groupthink in our approach to teamwork interventions in health care? Med Educ 50(4): 400-408.

- Sunderji N, Waddell A, Gupta M, Soklaridis S, Steinberg R (2016) An expert consensus on core competencies in integrated care for psychiatrists. General Hospital Psychiatry 41: 45-52.

- Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF (2013) Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: a qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J Interprof Care 27(5): 373-379.

- Bailey D (2010) Interdisciplnary working in mental health. New York.

- Blomqvist S, Engstrom I (2012) Interprofessional psychiatric teams: is multidimensionality evident in treatment conferences? J Interprof Care 26(4): 289-296.

- Bookey BS, Markle RM, Mc Key, Akhtar DN (2017) Understanding interprofessional collaboration in the context of chronic disease management for older adults living in communities: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 73(1): 71-84.

- Bruner P, Waite R, Davey MP (2011) Providers' perspectives on collaboration. Int J Integr Care 11: e123.

- Deber R, Baumann A (2005) Barriers and facilitators to enhancing interdiscplinary collaboration in primary health care. The Conference Board of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

- Desplenter FA, Laekeman GM, Simoens SR (2009) Pathway for inpatients with depressive episode in Flemish psychiatric hospitals: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst 3(1): 23.

- Tofthagen R, Fagerstrom LM (2010) Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis--a valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scand J Caring Sci 24(Suppl 1): 21-31.

- Tomizawa R, Yamano M, Osako M, Misawa T, Reeves S, et al. (2014) The development and validation of an interprofessional scale to assess teamwork in mental health settings. J Interprof Care 28(5): 485-486.

- Eisenberg L, Guttmacher LB (2010) Were we all asleep at the switch? A personal reminiscence of psychiatry from 1940 to 2010. Acta Psychiatr Scand122(2): 89-102.

- Ghesquiere AR, Pinto RM, Rahman R, Spector AY (2015) Factors Associated with Providers' Perceptions of Mental Health Care in Santa Luzia's Family Health Strategy, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(1): ijerph13010033.

- Walker LO, Avant KC (2005) Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. (4th edn), USA.

- Schroder C, Medves J, Paterson M, Byrnes V, Kelly C, et al. (2011) Development and pilot testing of the collaborative practice assessment tool. J Interprof Care 25(3): 189-195.

- Pollard KC, Miers ME, Gilchrist M (2004) Collaborative learning for collaborative working? Initial findings from a longitudinal study of health and social care students. Health Soc Care Community 12(4): 346358.

- Novella EJ (2010) Mental health care and the politics of inclusion: a social systems account of psychiatric deinstitutionalization. Theor Med Bioeth 31(6): 411-427.

- Haggarty JM, Rayan NKD, Jarva JA (2010) Mental health collaborative care: a synopsis of the Rural and Isolated Toolkit. Rural Remote Health 10(3): 1-10.

- Irajpour A, Alavi M, Abdoli S, Saberizafarghandi MB (2012) Challenges of interprofessional collaboration in Iranian mental health services: A qualitative investigation. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 17(2 Suppl 1): S171- 177.

- Lee E, Kealy D (2014) Revisiting Balint’s innovation: enhancing capacity in collaborative mental health care. J Interprof Care 28(5): 466-470.

- Corcle M (1982) Critical issues in the functioning of interdisciplinary groups. Small Group Behavior 13(3): 291-310.

- Kenna MH (2000) Nursing Theories and Models.

- Miller CJ, Grogan KA, Perron BE, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS, et al. (2013) Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta-analysis and metaregression to guide future research and implementation. Medical Care 51(10): 922-930.

- Petri L (2010) Concept analysis of interdisciplinary collaboration. Nurs Forum 45(2): 73-82.

- Sfetcu R (2013) Collaboration practices in mental health care: multidisciplinary teamwork or inder-professional collaboration groups? Mangement in Health 7(2):

- Voort TY, Meijel B, Goossens PJ, Hoogendoorn AW, Draisma S, et al. (2015) Collaborative care for patients with bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 206(5): 393-400.

- Rensburg AJ, Fourie P (2016) Health policy and integrated mental health care in the SADC region: strategic clarification using the Rainbow Model. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 10: 49.

- Wormer A, Lindquist R, Robiner W, Finkelstein S (2012) Interdisciplinary collaboration applied to clinical research: an example of remote monitoring in lung transplantation. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 31(3): 202210.

© 2017 Lam AHY , et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)