- Submissions

Full Text

Cohesive Journal of Microbiology & Infectious Disease

Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Patients Attended to Alribat University hospital, Khartoum State, Sudan, 2017

Mohammed HMN*, Siddig HS, Mohammed BA, Mohammed AE, Ahmed HH, Abdalgadir HF, Alameen NF, Mahmoud MI

Department of Parasitology and Medical Entomology, Sudan

*Corresponding author:Mohammed HMN, Department of Parasitology and Medical Entomology, Sudan

Submission: December 30, 2018; Published: March 26, 2019

ISSN 2578-0190 Volume2 Issue4

Abstract

Intestinal parasites comprise major health problems, especially in the tropical and sub-tropical regions. In developing countries, it is estimated that some 3.5billion people are affected, and that 450 million are ill as a result of these infections, the majority being children. Cross-sectional hospital-based study. It was conducted in Alribat University hospital, Khartoum State and aimed to estimate the distribution of Intestinal parasites among the patients in the study area. 120 stool samples were collected and analyzed by direct saline stool preparation and formal-ether Concentration Technique. Results showed that, 75(62.5%) stool samples were positive by the formal-ether Concentration Technique. While 55(45.8%) were positive by the direct saline stool preparation. Intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the male patients (65.7%) than the females (57.4%). Furthermore, they were more prevalent among the age group 5 to 10 years old (85%). The study concludes that Intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the male patients and among the age group 5to 10 years old. The study recommends using formal-ether Concentration Technique for diagnosis of Intestinal parasites.

Keywords: Prevalence; Intestinal Parasites; Infection; Khartoum; Sudan

Introduction

Parasitic infections are a main community health problem worldwide; particularly in the developing countries and constituting the greatest cause of illness and sickness. It is estimated that some 3.5 billion people are affected, and that 450 million are ill as a result of these infections, the majority being children [1]. These infections are regarded as a serious public health problem, as they can cause iron deficiency anemia, growth retardation in children and other physical and mental health conditions [2]. The high prevalence of these infections is closely correlated with poverty, poor environmental hygiene and impoverished health services. Current assessments suggest that at least one third of the total population in the world is infected with intestinal parasites. The majority is living in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. The prevalence of the intestinal parasitic infections varied from one region to another and it also depends largely on the diagnostic methods employed and the number of stool examinations done [3]. Sudan is one of the most important countries known to be endemic for many diseases including those caused by intestinal parasites. Currently, there is scarcity of available literature regarding the prevalence of parasitic infections from Khartoum State hospitals; therefore, little is known about intestinal parasitic infections in the inhabitants. Therefore, the aim of this study was to estimate the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients attending Alribat University hospital in Khartoum State, Sudan [4].

Rationale

Intestinal parasitic infections are one of the biggest socioeconomic and medical problems. Epidemiological studies show that parasitic infections are among the most common infections and one of the biggest health problems of the society worldwide [5]. These infections cause serious damage to children’s development in non-developed countries and are related to failure to thrive, reduced physical activity and learning power [6]. Intestinal parasite infections lead to several complications, however, most of cases were being asymptomatic carriers and usually tend to be chronic. Helminthic infestation lead to nutritional deficiency and impaired physical developments which will have negative consequences on cognitive function and learning ability [7].

Objectives

General objective: To estimate the prevalence of intestinal parasites among patients attending Alribat University hospital, Khartoum State, Sudan.

Specific objectives:

A. To compare the sensitivity of wet preparation and formalether concentration technique for diagnosis of intestinal parasites.

B. To compare the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients according to gender.

C. To compare the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients according to age.

D. To compare the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients according to parasite.

Literature review

Abdelsafi et al. [8], in Bashair hospital, Elengaz Area, Khartoum state, reported that the overall prevalence of intestinal parasite infections was 64.4%. The common intestinal parasites were Giardia lamblia, Hymenolepis nan, Taenia saginata, Entrobius vermicularis, Schistosoma mansoni and Entamoebia histolytica. Most of infected children were suffering from single infection and two types of parasite. Many cases were being subclinical cases while the rest of infected children suffered from different clinical features associated with intestinal parasites such as nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, flatulence, mucus, constipation, perianal itching and bloody stool. The prevalence of intestinal parasite infection was high in children; however, a considerable number of cases were asymptomatic. Abdelaziz et al. [9], in Central Sudan, In total, 142(90.4%) of 157 patients harboured at least one type of intestinal parasite. A lumbricoides, H. nana. E. histolytica and G. lamb were the most common parasites found with prevalence rates 32.5%, 30.6%, 33.1% and 19.7%, respectively. Out of 157 children, 29(18.5%) Harbored more than two parasites. Teklu, et al. [10] found that overall prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections (single and multiple infections) was 39.9% in a hospital-based study conducted in area health center where is located at 505 kms South of Addis Ababa. Also, in a study carried out by Rashid et al., (2011). in patients in Bareilly District health center, found that the prevalence of intestinal parasite was 22.81% [7]. Prevalence of Intestinal parasites was 42.8% in hospitals of Chandigarh, North India. Also [4] reported that in rural Peshawar, approximately 66% were found positive for various intestinal helminths infestation. Gashaw, et al. [3] in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia found the prevalent intestinal parasites were. Ascaris lumbricoides, S. stercoralis, T. trichiura, hookworm, and G. lamblia, Giardia lamblia was more frequent (33.4%) than other intestinal parasites. Tariq [11] reported that in children in Thi-Qar, Southern Iraq, the prevalence of Giardia lamblia was 23.7%. These parasites are often associated with contaminated water and food. Omar, (2015) in Hail hospital, Northwestern Saudi Arabia. found that the overall prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection was 45.38% (59 cases). Forty-four (33.84%) were found to be infected with one or more intestinal protozoa, 5(3.84%) were infected with helminthes and 10(7.69%) had mixed infection with both helminthes and protozoa. The most common intestinal helminth detected was Ancylostoma duodenale (n=5,3.84%), followed by Ascaris lumbricoides, Taenia sp. and Trichuris trichiura (n=2 for each species, 1.5%). For intestinal protozoa, the coccidian, Cryptosporidium parvum (n=25, 19.23%) was the most common followed by Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (n=21,16.15%), Giardia lamblia (n=15,11.54%), Entamoeba coli (n=5, 3.85%) and Blastocystis hominis (n=3,2.30%). The prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in females was significantly higher than in males Heidari and Rokni, (2003) in Day-care Centers in Damghan-Iran reported that at least 68.1 percent of the individuals tested, were infected with one species of pathogen or non-pathogen parasites. The rate of infection for Enterobius vermicularis, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Entamoeba coli, Blastocystis hominis, Iodamoeba butschlii and Chilomastix mesnili was 33.8%, 26.2%, 2.4%, 3%, 4.8%, 5.8%, 4.8%, 2.7% and 4% respectively.

Materials and Methods

Study area: The study was conducted in Alribat University hospital, Khartoum State, Sudan.

Study duration: The present study was conducted throughout the period from 1/12/2016 to1/4/2017.

Study population: Male and female patients attending Alribat University hospital, Khartoum State, Sudan.

Study design: This was a cross-sectional hospital-based study to estimate the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients attending Alribat University hospital

Sample size: Stool samples were obtained from 120 patients, randomly selected.

Specimen collection: Stool specimens were collected from all patients. The specimens were collected following the quality control procedures. Apportion of the specimen was used for direct saline preparation; the other portion was fixed with 10% Formal water v/v. for further concentration and staining techniques, [12].

Stool examination

Macroscopical examination of stool: Faeces were examined macroscopically for faucal consistency and color. These may vary with diet, but certain clinical conditions associated with the parasite presence may show wet or loose stool consistency or even diarrhea. The faces were also examined for the presence of tapeworm segments or other helminths [13].

Microscopical examination of stool:

a) Direct saline stool preparation: All specimens were initially subjected to direct saline preparation. It was performed by suspending 2-5mg (match-head size) of stool in few drops of 0.9% Sodium Chloride solution and then 1-2 drops of 1% eosin solution were added to the suspension, If the consistency of the stool specimen was fluid. Otherwise logo’s iodine was added. Then covered with cover slip and examined under the microscope using 10x eye piece and 10x objective for screening, and then 40x objective for identification [14].

Formal-Ether Concentration Technique:

Materials:

a) 10%Formal water, v/v.

b) Diethyl ether

c) Sieve (strainer) with small holes, preferably 400-450μm in size.

Methods:

a. Using a rod or applicator stick, 1g of faeces emulsified in about 4ml of 10% (v/v) formol water contained in a screw cap bottle.

b. Another 3 ml of 10% formal water were added, the bottle was caped, and mixed well by shaking.

c. The emulsified faeces sieved, and the eluent was collected in beaker.

d. The suspension was then transferred to a conical tube made of strong glass, and 3ml of diethyl ether added to this suspension.

e. The tube was stoppered and mixed for 1 minute. Then the stopper loosen and immediately centrifuged at (3000 rpm) for 1 minute.

f. The layer of faucal debris loosed from the side of the tube using an applicator stick and the faecal debris discarded and the formal water and the sediment remained.

g. The sediment was then transferred to a slide and covered with a cover slip.

h. The preparation examined microscopically using the 10x eyepiece and objective for scanning the smear and using 40x objective for identification of cysts and eggs [15].

Statistical analysis:

After gathering the data including sex, age and parasite species, the data were analyzed by SPSS 6.0 based on the study purposes. chisquare test was used, and t-test was used to compare quantitative variables [16].

Results

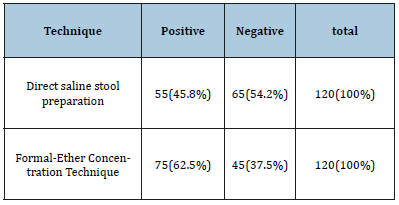

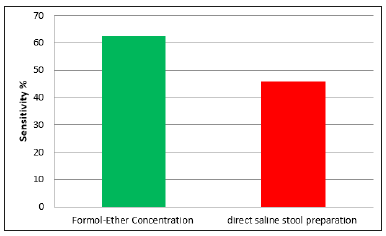

Results of comparative evaluation of stool examination techniques for detection of intestinal parasites.

A total of 120 stool samples were analyzed by direct saline stool preparation and Formal-Ether Concentration Technique. Results presented in Table 1 shows that, 75 (62.5%) stool samples were positive by the Formal-Ether Concentration Technique and 55 (45.8%) were positive by direct saline stool preparation. Diarrhea was present in 48 (40.0%) of total stool samples detected by microscopical examination Figure 1.

Table 1:

Figure 1:Comparative evaluation of stool examination techniques for detection of intestinal parasites.

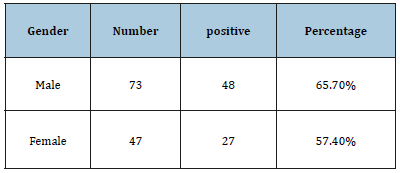

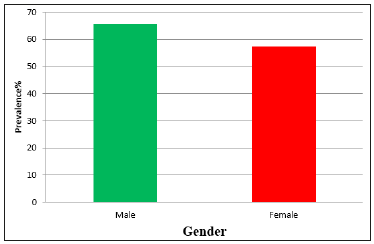

The distribution of intestinal parasites among patients, according to the gender

By using the Formal-Ether Concentration Technique (the most sensitive) the study found that intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the males (65.7%) than the females (57.4%). Table 2, Figure 2.

Table 2:

Figure 2:Showing the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients, according to the gender.

The distribution of intestinal parasites among patients, according to the age

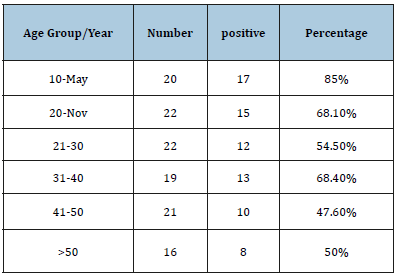

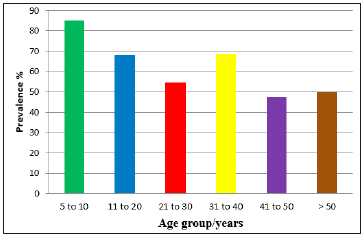

The study found that intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the age group 5 to 10 years old (85%). While it was less prevalent in age group 41to50 years old (47.6%). Table 3, Figure 3.

Table 3:

Figure 3:Showing the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients, according to the age..

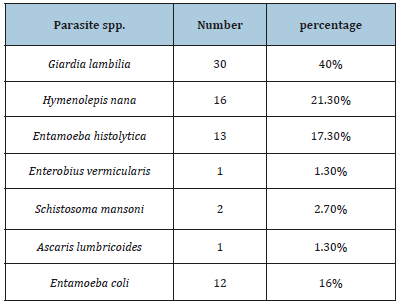

The distribution of intestinal parasites among patients, according to the parasite species

The study found that Giardia lamilia was the most prevalent parasite among the patients (40%), Followed by Hymenolepis nana (21.3%). While the lowest prevalence was recorded for Ascaris lumbricoides and Enterobius vermicularis (1.3%). Table 4, Figure 4.

Table 4:

Figure 4:Showing the distribution of intestinal parasites among patients, according to the parasite species.

Discussion

Several studies of intestinal parasites have tended to focus on adults, with little or no emphasis on hospitals patients. This study found that Formal-Ether Concentration Technique is the most sensitive method for diagnosing the intestinal parasites. This result was agreeing the result of Hussien, et al. (2009). Who found that Formal-Ether is the best technique for diagnosing the intestinal parasites [17]. By using the most sensitive method, our study found that the infection rate of the intestinal parasites among patients of Alribat University hospital, Khartoum State, Sudan, Was 62.5%. While [8], found that the infection rate among patienis in Elengaz area was 64.4%10. The study found that intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the male spatients (65.7%) than the females (57.4%), this may be an indication that the tow genders are not equally exposed to infection. In agreement to the findings of [18]. Who found that intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the male patients (37%) than the females (28%) [18]. On the other hand, the study found that intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the age group 5 to 10 years old (85%) this may be due to the low hygienic measurements of the young children. While it was less prevalent in age group 41 to 50 years old (47.6%). Contrary to the findings of [19]. Who found that there was no significant difference in the prevalence between all age groups of patients [19]. Our study reported that the most prevalent intestinal parasite specie among the patients was Giardia lambilia (40%), Followed by Hymenolepis nana (21.3%). This is in agreement with [8] who found that Giardia lambilia (33.4%) and Hymenolepis nana (26.4%) were the most prevalent parasites among the patients of Elena Area, Khartoum [18]. The clinical features associated with intestinal parasites were nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, mucus, constipation, perianal itching and bloody stool. However, a considerable number of cases were remaining subclinical [20-24].

Conclusion

This study concludes that Formal-Ether Concentration Technique is the best method for diagnosing intestinal parasites [25-28]. Intestinal parasites were more prevalent among the age group 5 to 10 years old and more prevalent among the male patients than the females. The most prevalent parasite is G. lambilia.

Recommendations

a) Health education.

b) Early diagnosis and early treatment of intestinal parasitic infections.

c) improve sanitation and personal hygiene.

d) Further studies must be done, with large sample size and other diagnostic methods to detect coccidian intestinal parasites. were remaining subclinical [20-24].

References

- Damen JG, Luka J, Lugos M (2011) Prevalence of intestinal parasites among pupils in rural north eastern, nigeria. Niger Med J 52(1): 4-6.

- Faten AA (2008) Is intestinal parasite infection still a public health concern among Saudi children. Saudi Med J 29(11): 1630-1635.

- Gashaw A, Afework K, Feleke M, Moges T, Kahsay H (2008) Prevalence of bacteria and intestinal parasites among food-handlers in Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr 26(4): 451-455.

- Ikram U, Ghulam S, Sabina A, Muhammad H (2009) Intestinal worm infestation in primary school children in rural peshawar. Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences 7(2): 132-136.

- Mamoun MM, Abubakr IA, ElMuntasir TS (2009) Frequency of intestinal parasitic infections among displaced children in Kassala Town. Khartoum Medical Journal 2(1): 175-177.

- Rashid MK, Joshi M, Joshi HS, Fatemi K (2011) Prevalence of intestinal parasites among school going children in bareilly district. NJIRM 2(1): 35-37.

- Sehga lR, Gogulamudi VR, Jaco JV, Atluri V (2010) Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school children and pregnant women in a low socio-economic area, Chandigarh, North India. RIF 1(2): 100-103.

- Gabbad AA, Elawad MA (2014) Prevalence of Intestinal Parasite Infection in Primary School Children in Elengaz Area, Khartoum, Sudan. Academic Research International 5(2): 86-90.

- Ahmed AM, Afifi AA, Malik EM, Adam I (2010) Intestinal protozoa and intestinal helminthic infections among schoolchildren in Central Sudan. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 3(4): 292-293.

- Teklu W, Tsegaye T, Belete S, Takele T (2013) Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among highland and lowland dwellers in Gamo area, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 13: 151.

- Tariq KH (2010) Prevalence and related risk factors for giardia lamblia infection among children with acute diarrhea in Thi- Qar, Southern Iraq. Thi-Qar Medical Journal 4(4): 68-74.

- Ferreira CB, Marcal O (1997) Intestinal parasitoses in school children of martinesia district, Uberlandia, MG: a pilot study. Rev Soc Braz Med Trop 30(5): 373-77.

- Lu KJ, Bae YT, Kim DH, Deung YK, Ryang YS (2002) Status of intestinal parasites infections among primary school children in Kampongcham, Cambodia. Korean J Parasitol 40(3): 153-155.

- Awasthi S, Pande VR (1997) Prevalence of malnutrition and intestinal parasites in pre-school slum children in Lucknow. Indian Pediatr 34(7): 599- 605.

- Kappus KD, Lundgrenjr RG, Juraner DD, Roberts JM, Spencer HC (1994) Intestinal parasitism in the United States: update on a continuing problem. Am J Trop Med Hyg 50(6): 705-713.

- Miller R, Pinales CD, Lopez AC, Lechuga LM, Tren D (1994) Cryptosproidium parvum in children with diarrhea in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg 51(31): 322-325.

- Siddig HS, Ismail AA, Musa HA, Kafi SK, Ibrahim AM, et al. (2011) Screening the Efficacy of Some Traditional Herbal Drugs for Treatment of Hymenolepis diminuta Infection in Rats. Sudan Journal of Medical Sciences 6(4): 271-276.

- Mohamed MM, Ahmed Al, Salah ET (2009) Frequency of intestinal parasitic infections among displsced children,Kassala Twon,Khart med 2: 175-7.

- Opara KN, Udoidung NI, Ukpong IG (2007) Genitourinary schistosomiasis among pre-primary schoolchildren in a rural community within the cross-river basin, Nigeria. J Helminthol 81(4): 393-397.

- Karrar ZA, Rahim FA (1995) Prevalence and risk factors of parasitic infections among under-five Sudanese children: a community-based study. East Afr Med J 72(2): 103-109.

- Magambo JK, Zeyhle E, Wachira TM (1998) Prevalence of intestinal parasites among children in southern Sudan. East Afr Med J; 75(5): 288- 290.

- Salim MI (1999) Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection in school children in Khartoum State. MD Thesis, Sudan.

- Bannaga AN (1992) Social and health profile among street children in Khartoum. MD Thesis, Sudan.

- Abdalla NE (1997) Blood diarrhea in Sudanese children in Khartoum State. MD Thesis, Sudan.

- Babiker MA (2002) Assessment of the use of different diagnostic techniques for the detection of intestinal parasites in food handlers in Khartoum State. MD Thesis, Sudan.

- Wadilo F, Solomon F, Arota A, Abraham Y (2016) Intestinal parasitic infection and associated factors among food handlers in south ethiopia: a case of wolaita sodo town. Journal of Pharmacy and Alternative Medicine 12: 5-10.

- Lu KJ, Bae YT, Kim DH, Deung YK, Ryang YS (2002) Status of intestinal parasites infections among primary school children in Kampongcham, Cambodia. Korean J Parasitol 40(3): 153-55.

- Baldo ET, Belizario VY, Deleon WU, Kong HH, Chung D (2004) Infection status of intestinal parasites in children living in residential institution in Metro Manila, the Philipines. Korean J Parasitol 42(2): 67-70.

© 2019 Mohammed HMN. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)