- Submissions

Full Text

Biodiversity Online J

The Concept of Biodiversity Conservation Viewed through Philosophies of the Global South: Andean Buen Vivir, African Ubuntu and Buddhist Happiness

Dorine Van Norren1* and Henkjan Laats2

1Associate Researcher, Van Vollenhoven Institute for Law, Governance and Society, Leiden University, Netherlands

2Cross Cultural Bridges, Netherlands

*Corresponding author: Dorine Van Norren, Associate Researcher, Van Vollenhoven Institute for Law, Governance and Society, Leiden University, Netherlands

Submission: March 05, 2022; Published: April 05, 2022

ISSN 2637-7082Volume2 Issue2

Abstract

Mainstream conservation strives at sustainable management of natural resources by protecting areas from human intervention. This is problematic in the view of many indigenous communities who strive to live in harmony with Nature 1, whose lifestyles depend on Nature and who embrace concepts of wellbeing where man and Nature cannot be separated. In such a cosmovision Nature is not considered as a resource, but as a web of life in which living and non-living beings are interconnected and interdependent. This article refers to three concepts of conservation: mainstream conservation, post-wild world conservation, convivial conservation. The latter leaves room for inclusion of indigenous worldviews, of which we analyze three: African Ubuntu, Buddhist Happiness and Andean Buen Vivir. We offset these with examples of problematic conservation practices, often originating in mainstream conservation practices. The Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) Parties propose to expand these areas to 30% in 2030 to be decided in 2022. In ‘Western’ (globalized) culture conservation is a necessary supplement to the logic of economic growth and serves to offset the negative consequences. Sustainable growth thus promotes more of the same instead of advancing lifestyles in harmony with Nature. A principal aim of conservation is to maintain or increase biodiversity, with a focus on the conserved or protected areas. A crucial question is whether this dualist conservationist approach in which we divide conservation areas and human populated areas indeed enhances biodiversity, considering not only the conservation areas, but the planet as a whole.

Keywords: Conservation; Biodiversity; Buen vivir; Happiness; Ubuntu; Indigenous; Convivial conservation

Introduction

According to Massarella [1], currently one can distinguish three biodiversity conservation conceptualizations: The first conceptualization aligns with the ‘naturalism’ paradigm, which envisions a world in which ‘wild’ and ‘self-willed’ nature flourishes separately from humans. This goal is the basis of proposals for transformative change, such as ‘Half Earth’ and ‘Nature Needs Half’, both of which call for major increases in strictly protected areas worldwide until at least 50% of biodiverse terrestrial and marine areas are protected. In the second conceptualization, transformative change is framed within the idea of the Anthropocene: we are living in a ‘post-wild’ world where nature no longer exists separately from humans, so biodiversity conservation must align with this reality. Proponents, often referred to as ‘new conservationists’, advocate a shift away from ideas of wilderness as the basis of conservation and instead envision a world where people and nature coexist in dynamic configurations, including in urban areas. A third conceptualization is grounded in the pursuit of justice, with the goal of transformative change in conservation being a more equitable world for both humans and nonhumans. Here, the goal is ‘just transformations’ whereby change is combined with the pursuit of environmental justice. This goal can be identified in some broader transformations to sustainability literature. Just transformations highlights power, politics and persistent injustices in environmental discourses and management, reconciling past injustices, and questioning whose perspectives, values and worldviews are driving transformative change. As a method, this article will use these conceptualizations to look at different practices of conservation and specifically indigenous ones and offset them with mainstream practices of conservation and related problems. The first two conceptualisations avoid the discussion on system change and consider humans as separate from nature. This is a dualistic vision, that does not match with more ancient indigenous cosmovisions. The third vision, on the other hand, comes close to concepts of rights of Nature and ‘convivial conservation’ (explained below). The latter concept advocates to incorporate knowledge and practice from the global South, such as the African Ubuntu concept and the South-American Buen Vivir concept [2]. To this can also be added Gross National Happiness (GNH) in Bhutan. Therefore, a thorough analysis is needed on the cosmovisions from the global South and whether they indeed coincide with the ‘goal of transformative change in conservation being a more equitable world for both humans and non-humans’.

The indigenous worldviews contain proposals that relate with other than conventional principals such as: Living in harmony with Nature, rights of Nature and Mother Earth, (biocentric) cooperation, and embrace of indigenous Good Living (Buen Vivir); mutual aid, sharing and respecting different generations (African Ubuntu); (inner) happiness and balance, peace, empathy and respect for all sentient beings (Gross National Happiness, GNH). These ways of life are supported by the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (2007) of which a cornerstone principle is that of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). Before recognition of indigenous peoples was regulated in the ILO 169 convention (1989). For Latin America there is also the ‘Declaración Americana sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas’, of the Organisation of American States (2007). The question is which kind of conservation does the world need? Can these practices exist at the same time, or is the first, traditional Western, conservation definition in need of transformation? In this article we will discuss African Ubuntu philosophy and Buddhist happiness as practiced in Bhutan as well as Buen Vivir as practiced in the Andes countries, as an alternative to conventional conservation practices. These fall under the indigenous community and conservation approach (ICCA) proposals and the newly coined concept of convivial conservation.

Foot Note1 A capital is added to note the sacredness of Nature in indigenous viewpoints. before this, WWF, https://wwf.panda.org/discover/people_and_conservation/our_principles/

Problems with Conventional Conservation Practices

Conventional mainstream conservation is defined as ‘planned management of a natural resource to prevent exploitation, destruction, or neglect. The longstanding practices of Western conservation have also inspired the Sustainable Development Goals, specifically goal 15 (reviewed below). A principal aim of conservation is to maintain or increase biodiversity, with a focus on the conserved or protected areas. A crucial question is whether this dualist conservationist approach in which we divide conservation areas and human populated areas indeed enhances biodiversity, considering not only the conservation areas, but also the areas that are not protected. For example, the definition of conservation of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and other conservation NGOs- rests on anthropocentric principles of separation of nature and people. WWF did adopt social principles: Respecting people’s rights, equity, enhancing natural assets, addressing governance, and balance between production and consumption and environmental costs2 These are clearly not (yet) a transformative rights of Nature or earth centric perspectives. WWF also signed the Conservation Initiative on Human Rights Framework in 2009 and is a founding member of the Conservation and Human Rights Initiatives3. Since 2008 the WWF recognized tensions between conservation practices and indigenous peoples and tries to address these through a Statement of Principles [3]. It recognizes indigenous control of territories and FPIC, also in the use of indigenous knowledge: ‘WWF recognizes the right of indigenous peoples to exert control over their lands, territories, and resources, and establish on them the management and governance systems that best suit their cultures and social needs, whilst respecting national sovereignty and conforming to national conservation and development objectives.’ (para9). ‘Consistent with WWF conservation priorities, WWF will promote and advocate for the implementation of Article 29 of the UN Declaration the Rights of Indigenous Peoples calling on States to establish programmes to fulfil “the right of indigenous peoples to conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources”, and Article 7 of the ILO Convention 169 calling on governments to take measures, in co-operation with the peoples concerned, to protect and preserve the environment of indigenous territories.’ (para 26). ’WWF will not promote or support, and may actively oppose, interventions which have not received the prior free and informed consent of affected indigenous communities, and/or would adversely impact directly or indirectly on the environment of indigenous peoples’ territories, and/or would affect their rights.’ (para 30) ‘(…) To ensure that they are able to fully participate in decisions about the use of knowledge acquired in or about the area they inhabit (…)’ (para 31). [3]. According to international NGO’s. however, these principles are not always respected (see also testimonials below). An infamous case are the allegations of Buzzfeed News [4] in 2019 of ‘severe human rights abuses carried out by park guards supported by WWF in a scandal that led to the appointment of an independent review panel’ [5]. Apparently, WWF knew of the wrongdoings [6]. Other examples are given below. Other problems with the mainstream conservation approach entail amongst others indigenous peoples being evicted from their lands, whilst tourism and trophy hunting continue, thus further increasing an inequality gap. Wealthy people with unsustainable modern lifestyles have access to nature whilst local communities, often (not always) living in harmony with their natural surroundings, are forced to give up their lifestyle and integrate in the ‘modern’ world. Thus, conservation serves to offset an unsustainable Western inspired (now global) lifestyle and yet increasing the number of people forced to adopt that lifestyle. Conservation can also lead to severe human rights abuses.

Foot Note2Our Principles, WWF, https://wwf.panda.org/discover/people_and_conservation/our_principles/

3WWF Social Principles, https://wwfint.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_social_principles_and_policies.pdf

The Growth Logic, Targets and Indicators approach and Conventional Conservation

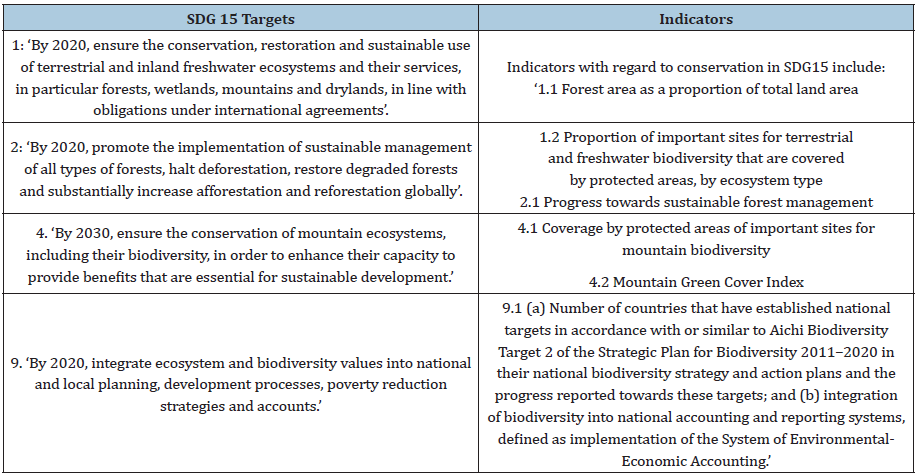

Table 1: SDG 15 some indicators.

Since the death of ideologies in development cooperation, the target and result based management approach has taken over in development policies, starting with the Millennium Development Goals in 2000 [7]. It is left undefined how and by which strategies the so called ‘sustainable development’ should be achieved. These frameworks are driven by a Western epistemology of ‘knowing is measuring’, finding their basis in natural sciences and a demystification of reality, at the same causing a loss of meaning that is often found in spirituality such as in customary ways of life [8]. In terms of conservation the SDGs aims are expressed in SDG154 which includes amongst others the targets in Table 1 above. The SDGs draw partly on the 1992 Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) (ratified by 192 States). This is still the cornerstone policy framework for conservation, internationally. The Aichi principles of 2010, linked to CBD, do mention the importance of indigenous people, notably in Target 18:

‘Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations

and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for

the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their

customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to

national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully

integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention

with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local

communities, at all relevant levels5.

Parties to the CBD were set to adopt a post-2020 global

biodiversity framework in October 2020, when the conference

of parties held their annual meeting. The agenda included the

doubling of protected areas from the target of 17%, agreed in Aichi

(Japan) (Aichi target 11), to 30%. This means one third of all land and sea areas would be conservation area in 20306. The declaration

of October 2021 noted the call for 30 by 30 (page 3)7 It is now set

to be the main outcome of the CBD’s COP 15 meeting in Kunming,

China, in April–May 2022 [9]8 .

CBD nowadays also refers to Harmony with Nature9, as

stated in the 2050 vision for biodiverstity living in harmony

with Nature, adopted in Nagoya in 2010 when previous targets

were not achieved [10] and elaborated in a strategy decision

[11]. As Lim [12] states: ‘Yet biodiversity is threatened globally

to an extent never before witnessed in human history’. (On the

feasibility of CBD’s strategy, see for example [12]). This policy

target called ‘30 by 30’ is to be achieved in 10 years (in 2030) but

is contentious amongst indigenous peoples and ‘exposing fault

lines in the modern conservation movement over who should

control biodiversity protection and where funding should be

directed’ [5]. It provides a convenient alliteration that adds to the

results and numbers drive, characteristic of current development

planning, but the basis and strategy for it are unclear. Even though

the proposal includes so called OECMs, ‘other effective area-based

conservation measures’ (including indigenous controlled areas)

next to conventional protected areas, it is feared that conventional

conservation measures will take the lead. ‘However, we also know

from experience that despite provisions in current CBD framework

to include OECMs in global conservation targets, strict conservation

regimes have remained the default choice in the Global South’

[13]. Moreover, a study predicts the displacement of 300 million

people with these measures. When 50% of the planet would

be protected, as mainstream conservationists call for [14], this

number may increase to a little less than 2 billion (depending on

which areas are chosen, either 1.6 (minimal population affected),

1.7 (minimal agricultural land) or 1.9 (minimal land) [2,15]. Even

if the world chooses this path, (financial) compensation according

to international guidelines is unfeasible [5]. For the resettlement

of 300 million people US$1 trillion would be needed. Relocation

costs for 1.2 – 1.5 billion people living in unprotected important

biodiversity conservation areas range between US$4.0 to US$5.0

trillion [15].

4 UN SDGs Goal 15, https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal15 and Biodiversity and ecosystems .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform (un.org)

5Aichi Biodiversity Targets on: https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/

The alternative to conservation: Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCA)

Territories that are de facto governed by indigenous peoples (or local communities), in harmony with Nature leading to (increased) biodiversity conservation are also referred to as Indigenous and community conserved areas (ICCAs)10. These territories are often run according to traditional cultural practices, though also relatively new practices and communities fall under the ICCA term11. ‘Territorios del buen vivir’ and sacred natural sites are one of the ICCA forms12 [16]. They form part of what is referred to as OECM above. Even though often much older than current conservation practices, they are not always (politically or legally) recognized and often threatened by modern day acquisition of land by public or private parties, or other practices that lead to loss of indigenous identities. These include development interventions such as ‘modern’ education, payment for ecosystem services, disempowering centralization of government, unsustainable resource extraction (oil, mining, logging), conflicts and (climate change related) natural disasters13. In Latin American countries, there are different forms of recognition of indigenous territories such as in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru [17]. The CBD was advised on ICCA’s in 2010. ICCAs emerged only in the early 2000’s in formal conservation circles. ‘International policies and programmes, notably those of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), encourage today all countries to recognise and support ICCA.’ [18].

Indigenous ways of looking at conservation: Harmony with Nature

The UN showed that indigenous peoples are far better at conservation, especially when collective indigenous land rights have been recognized [19]. Their report recommends a set of investments and policies with indigenous peoples:

I. Strengthening of collective territorial rights;

II. Compensate indigenous and tribal communities for the

environmental services they provide;

III. Facilitate community forest managemnt;

IV. Revitalize traditional cultures and knowledge; and

V. Strengthen territorial governance and indigenous and

tribal organizations.’

For example, in Guatamala results in forest management in indigenous areas are much better than in protected areas [20]. ‘If you look at all the different studies out there, it’s very clear that the regions where Indigenous people in particular have control over their forests, and by control I mean secure titles, rights, and recognition of their traditional territories, that’s where we see those forests intact and biodiversity observed to a large degree,’ [5]. We will now discuss three alternative worldviews from the Global South – Ubuntu, Happiness and Buen Vivir of which Buen Vivir can be said to be most biocentric.

Foot Note6 Draft monitoring framework for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework for review https://www.cbd.int/sbstta/sbstta-24/post2020-monitoring-en.

pdf

7CBD (first) Kunming Declaration, 13 October 2021, https://www.cbd.int/doc/press/2021/pr-2021-10-13-cop15-hls-en.pdf

8Meetings documents on: https://www.cbd.int/meetings/COP-15

9Adopted by CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011- 2020 and Aichi Targets by decision X/2. https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=12268#:~:text=The%20

purpose%20of%20the%20Strategic,action%20by%20all%20Parties%20and

10Defining characteristics are: (1) a community tied to a territory, which exercises (2) management decisions, leading to (3) preservation of the habitat,

including species, genetic diversity, ecological functions, and associated cultural values. See Feyarabend and Farvar 2019 and Three defining

characteristics for ICCA’s, ICCA Consortium, https://www.iccaconsortium.org/index.php/discover/

11Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCA), Biodiversity A-Z, 24 December 2020, https://www.biodiversitya-z.org/

content/indigenous-peoples-and-community-conserved-territories-and-areas-icca

12Many names, a value in itself, ICCA Consortium, https://www.iccaconsortium.org/index.php/discover/

13Threats and challenges to ICCA’s, ICCA Consortium, https://www.iccaconsortium.org/index.php/discover/

African Ubuntu

The African philosophy of Ubuntu is a continent-wide philosophy, though the term Ubuntu features more in Southern African (Nguni) languages. The concept of brotherhood is a universal African concept featured under many different names. South Africa is one of the countries that has rooted its postapartheid transition and national development (partly) in cultural traditions of restorative justice, though the term Ubuntu is often lesser-known and its environmental dimension the least. In human terms Ubuntu is referring to humaneness and interconnectedness [21-23]. One’s individuality only exists through other people and thus we are collective beings rather than individual beings. Hence the saying ‘I am because we are’ [23-26]. In a broader sense Ubuntu emphasizes the interdependence of all life since philosophically it refers to the meeting of abstract being (ubu) and the life force being (ntu). This implies a need for compassion and mutuality [27]. Relations are paramount and deemed more important than abstract concepts such as development. Important is to recognize that these relations encompass the future and past generations [23], which are both connected to Earth (the place where the ancestors go and the resources the yet-to-be-born will need). Mbiti explains that land is the abode of forefathers; space and time are one in African thought, thus merging the geographical place with the events and persons once living and giving it meaning in life [27]. The ancestors are ‘living’ as long as they are remembered and thereby ‘living-dead’ [23]. Ties with the land and respect for the land are an integral part of Ubuntu. Indeed, there is no different word for disrespect to humans or to nature, both are a violation of Ubuntu. This is both reasoned from the perspective of logic that without care for nature the interdependence between people is threatened [23] and the mutual sharing between generations is needed, as well as from a more metaphysical perspective that all living being are perceived to be interdependent through a field of connectedness. Though critics may perceive this as old-fashioned, religious or a romantization of the past [28], Ubuntu has been articulated in concrete laws and policies, in for example South Africa. The most famous example is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TNC), aiming at harmonious relations and a forgiveness of the past. The idea of harmonious relations and a sharing of what one can call the commons is also the main ‘conservation’ principle of dealing with nature. This requires a cooperative spirit rather than a competitive outlook on life. The TNC (and its anchoring in the interim constitution of South Africa) also indirectly lead to Ubuntu jurisprudence on restorative justice though these do not directly address the environmental dimension [29,30]. This is addressed through the constitutional provision of respecting the needs of future generations (Section 24 of the South African Bill of Rights) as well as through provisions on cultural rights of communities, thus indirectly connected to the life philosophy of Ubuntu. Furthermore, South Africa has policies on transparent government dealings with its citizens, called Batho Pele, or People First (Batho is another word for Ubuntu, in Sotho language) [31]. These policies were instituted to overcome apartheid legacies and distrust of government. People articulate their connectedness to their land, earth and the ecosystems, as part of their identity. That encompasses both nature’s usefulness, its beauty, its place as the environing whole, and the sacredness of nature and linking it to prayers and taboos. The idea of taboo is an early conservation principle, whereby an area is declared prohibited. The elders may know the reasons because their vast experience with their habitat, but do not always explain them. By instilling fear or awe the prohibition becomes effective and is being observed and thus conservation achieved. The heart of conducting sustainable development is recognizing that a ‘selfish unselfishness’ is needed in relating to one’s environment. ‘Ubuntu underlines the shared human solidarity interest in living in harmony both with each other and with the earth. When people, timber and soil are simultaneously removed the spirit of Ubuntu is simultaneously violated in three intersecting ways’ (African interviewee) [8]. Though Ubuntu approaches a biocentric way of living as articulated in Buen Vivir, it is at the end more humancentric than biocentric, although interpretations vary from urban to rural and between different places and cultures. There is however no economically articulated Ubuntu policy in South Africa nor an environmental one. Ubuntu jurisprudence largely concentrates on social justice and criminal justice [29,30]. Implementation policies are based on mainstream conservation, though there are concerns of equitable access [31] and communities asking for cultural rights in for example mining projects such as in Xholobeni [32]. Conservation is understood from the Batho Pele policy perspective of improving the environment is improving the living conditions of people in health and recreational terms; at the same time redressing the apartheid legacy of inequality and forced removals from the land pose its own environmental challenges (interviewee of the conservation department of Cape Town[8]. South Africa was hailed for its energy transition deal, the ‘most impressive’ deal at COP26 in 2021 [33].

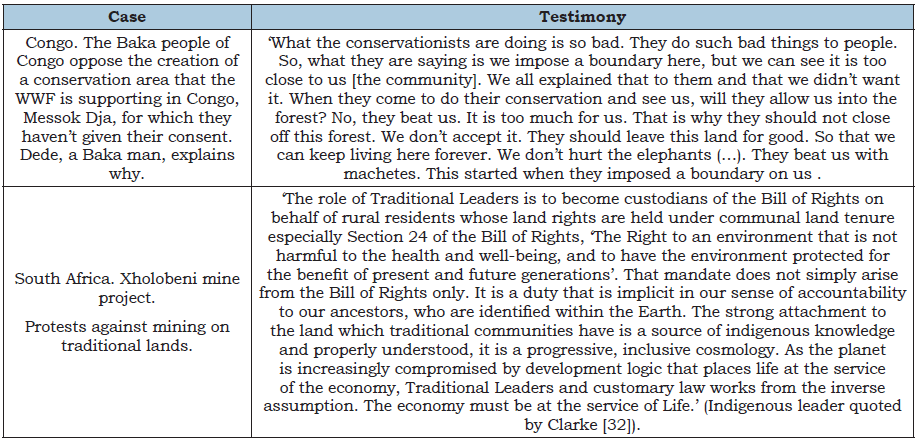

Testimonies from some communities in Africa on certain current conservation practices, go directly against customary ways of life, and involve violent repression. Conservation is no longer tied to the communities, who also do not bear responsibility for it. Separation of land and community is seen as the solution, which neither empowers the community nor the land and robs people of their identity. Projects are referred to as ‘doing their conservation’. For example, by the Baka people of Congo (Table 2).

Table 2: Congo and South Africa cases.

Bhutanese Gross National Happiness

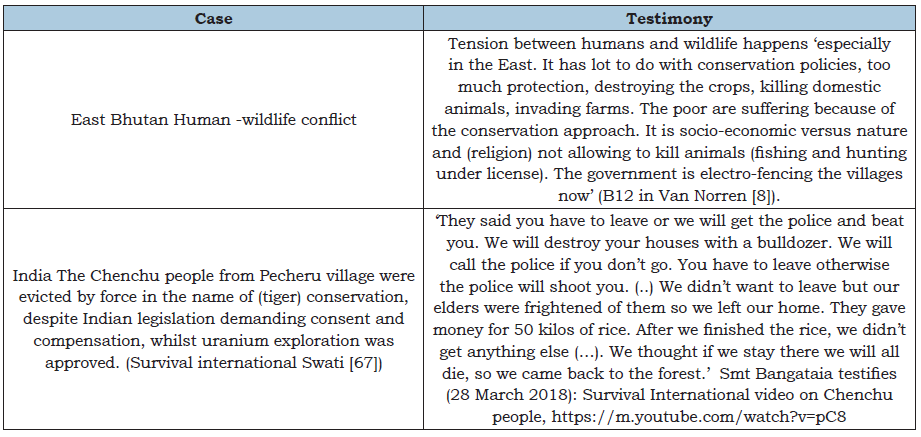

Like in Africa and Latin America, some countries in Asia have experimented with rooting their national development in cultural practices and in the case of Bhutan specifically in harmony with Nature. It has termed its national development logic Gross National Happiness, but this should be interpreted as Gross National Harmony or Gross National Peace, and not necessarily in the Western sense of (hedonic) happiness. Wellbeing in Buddhist philosophy after all depends on inner peace, balance and harmony with all living things. These living beings deserve empathy as is emulated in the saying ‘respect all sentient beings. All things are interdependent and this is referred to in the concept of codependent origination [8]. This also means the need for an empathic economy. All aspects of live need to be balanced to achieve wellbeing for all and thus the official policies rests on four intersecting pillars and nine domains in which these are measured. Pillar one encompassing culture defines identity. Pillar two regarding socio-economic development takes care of daily needs. Pillar three living in harmony with Nature requires care for the environment and the planet. Pillar four good governance ensures that society is efficiently run and democratic rights are respected. The measurement tool is embodied in a GHN index that includes nine yardsticks: psychological well-being, time use, cultural diversity and resilience, community vitality, education, health, good governance, ecological diversity and resilience14, and living standards [34]. This measurement tool is not necessarily a full reflection of Happiness or Buddhist philosophy but rather an instrument to counteract the dominant theory of GDP (Gross National Product) and economic growth [34,35], although GNH does not reject GDP measurement. The logic is that one never knows when material goods are enough or how it affects the person’s state of mind, and therefore one needs to cultivate inner peace (happiness) in all circumstances. One needs to find a balance between material and spiritual wellbeing and cultivate inner skills to deal with outer circumstances. These skills include compassion, walking the middle path, living in moderation and recognizing the interdependence of all things, including nature [8,34,36,37]. This view of live automatically requires a lifestyle that does not go at the detriment of other beings. Bhutan did not only base all its policies in its national philosophy of Buddhism but it also rooted it in its Constitution of 2008. The Bhutanese view of life does not give direct rights to Nature but rather refers to human guardianship of Nature, which could be construed as rights to Nature. The constitution refers to it as a duty of citizens, which citizens take seriously. The 2015 GNH survey revealed that a ‘large majority’ of the citizens feel ‘highly responsible’ for their environment [38]. The omission of rights of Nature in the constitution is partly because the government was worried of endless litigation by strict Buddhist monks [30] rather than opposing the idea of harmony with Nature. In Buddhist religion there are also rights for animals and plants; human rights extend to the environmental realm; this is implied in the idea of respecting the integrity of all life forms (sentient beings) [8]. Sentient does not only mean ‘living’, but also ‘conscious’. Consciousness can extend to what in the West are considered inanimate objects. Thus, Nature is considered sacred, both in Buddhist religion as in customary culture in Bhutan. Bhutan, in its policies, rather refers to biodiversity conservation. This is rooted in the constitution, which refers to a mandatory forest cover of 60%. Forests are the dominant ecosystem in Bhutan with 71 percent of the country under forest cover and an additional 10,4 % percent under shrubs. The total protected forest areas in the form of national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and biological corridors is a little more than half of the total land area [38]. The country has strict conservation laws. However, Bhutan has been ‘practicing environmental conservation long before it was referred to as such’ (Plannning Commission 1999, 21). National target 6 is ‘Carbon neutrality, climate and disaster resilient’. Under this program priorities are: Mainstreaming environment in all sectoral and local government plans; managing waste; exploring eco-friendly public transport system; enhancing mitigation and adaptation to climate change; strengthening preparedness and response to both natural and man-made disasters. It also includes water management and renewable energy [38]. Bhutanese formulate their commitment thus: ‘Environmental conservation is also valued widely throughout Bhutanese society as many citizens’ sources of livelihood are dependent on their natural environment, especially those working agriculturally. It is commonly believed that irresponsible activities in nature will lead to negative and therefore unhappy outcomes. Most Bhutanese accept the fact that the environment should be preserved for others and the future generation, limiting severe environmental degradation. Performing public service means taking a holistic view of things, which is thinking beyond ourselves and our time. It is thinking about future generations, about the animals, about the plants, and the environment they live in, or in other words, Mother Nature. Through this mind-set of public service, we conserve our natural environment. Bhutan has always recognized the central role environment factors play in human development. Pursuant to Article 5 (Environment) of the Constitution of Bhutan, every Bhutanese citizen shall ‘contribute to the protection of the natural environment, conservation of the rich biodiversity of Bhutan and prevention of all forms of ecological degradation including noise, visual and physical pollution.’ [39]. One of the main newspapers in Bhutan contended that proposals of mainstream conservation organizations – ‘agents of the anthropocene’ such as WWF (Worldwide Fund), CI (Conservation International) and TNC (The Nature Conservation) such as climate smart farming are ‘a new licence for business–as-usual’; and hails Bhutan’s policies for ‘food sovereignty.’ This while ‘Bhutan has not lost the sense of oneness with nature – Bhutan has not really entered the Age of Anthropocene – at least not yet.’ [32]. For further information [39-41]. However, biodiversity is still challenged by hydropower, as well as mineral extraction, agricultural modernization, road construction; rapid urbanization. Traditional co-operative land management is pressured of economic modernization. Conservation practices are under pressure by protests of farmers whose lifestyle may suffer from intrusion by wildlife, thus exposing human-wildlife conflicts. This is also partly due to migration by younger persons to urban areas, depopulating the rural areas [8]. A testimony is given in (Table 3). In part Bhutan’s development was determined by Indian cooperation programmes. This did not always lead to programmes in harmony with national culture. For example, most commons were abolished by the central state, though it contributed to environmental conservation [35]. Some are still protected by secondary laws pertaining to land and forests and common pasture. Buddhist Happiness can be considered in between biocentric and anthropocentric worldviews as in its belief system the human is considered as the ‘precious one’ (higher evolved than animals) which also implies carrying a larger responsibility to others [8]. Table 3 gives two testimonies from conservation gone wrong, in Bhutan and in India (Bhutan gets substantial cooperation and policy advice from India).

Table 3: Conservation gone wrong: testimonies from communities in Bhutan and India

Native Latin American Buen Vivir

In Latin America both Bolivia and Ecuador carried out policies based on indigenous philosophies centering around harmony with Nature. This they named Good Living or resp. Vivir Bien/Buen Vivir in Spanish. These policies are rooted in indigenous philosophy of the Andes people, called Quecha. The Quecha wisdom is called Sumak Kawsay, or living in plenitude, the fullest way of living, or the most beautiful (Summa) way of living (Kawsay). One could also translate it into the right way of living. For the political movement of indigenous peoples in Ecuador, the recognition of the variety of cultural communities or nations, is even more imperative than the concept of Buen Vivir [8]. This is called plurinationality (many nations in one state), which requires interculturality or cultural exchange [42]. Therefore, Buen Vivir is an open-ended concept. Though this is a Quecha perspective (Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile), it resonates with indigenous principles in many cultures on the Western hemisphere. Other communities have also claimed their rights such as the Afro-Ecuadorians and the Montubio (coastal peasants) [30]. The right way of living centers around reverence for Mother Earth from which all life is derived, and living in harmony with the Cosmos, all life forms and Nature [8,43,44,45]. This means humans live in partnership with the Earth and in reciprocity with Nature and the Earth, as much as in reciprocity with one another (just like the mutuality in Ubuntu). Community is therefore a central value and includes Nature [8,43,46]. Within this community exchange takes places (in different forms) and between different indigenous communities a cultural exchange. Like in Buddhist happiness there is an emphasis on addressing both spiritual and material needs. Like Ubuntu it embraces diversity and restorative justice geared towards harmony in relationships, going beyond current punitive justice paradigms. Since the concept is biocentric and not anthropocentric, the word environment does not fit, since it denotes that which environs the human. And since all are seen as equal and sacred, animate and inanimate, Nature and Earth (‘Pachamama’) are spiritual concepts. As the constitution of Ecuador contains the term Pachamama, it means that in theory the spirits are also constitutionally recognized [8]. Likewise, the constitution of Bolivia is based on indigenous concepts, though the constitution of Ecuador is the only one that directly recognized rights of Nature. In the indigenous mind all other rights (and governance systems) are derived from Mother Earth. The idea of linear development does not exist in Sumak Kawsay. Rather it focuses on circular process of growth and decay, and the integrality of life which lives in relationality, as well as the complementarity of masculine and feminine and the need for reciprocal exchange [30]. Looking at its many forms and linkages, Buen Vivir can be understood as both a critique of development understood as infinite economic growth, and a discursive turn that seeks to transcend modernity [43,47]. Ongoing debates about welfare, quality of life and ‘the environment’ have, according to the Uruguayan ecologist Eduardo [44], taken on new meaning in a ‘biocentric turn’, or what the French philosopher [48] refers to as a departure from ‘environmentalism in crisis’. This turn seeks to break away from the anthropocentric stance of modernity and assign new meaning to the environment by looking beyond the separation of Nature and culture to recognize their interconnectedness. As a result, any approach to the ‘environmental question’, including conservation, must overcome the binary between human and Nature, animate and inanimate, inviting dialogue with other ways of thinking about citizenship, such as from local knowledges [49].

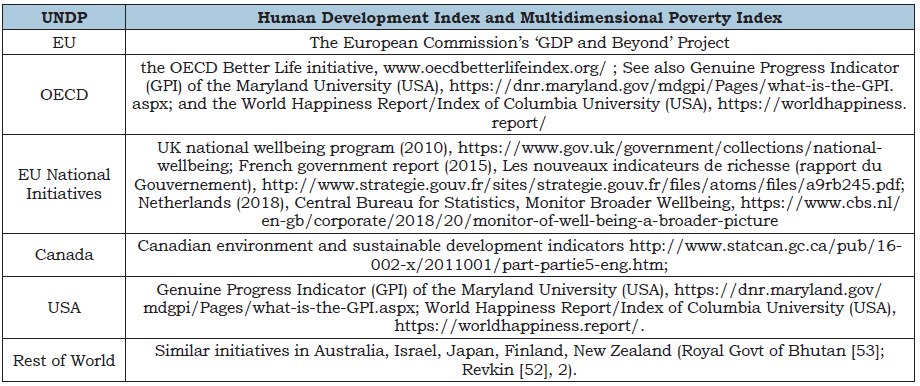

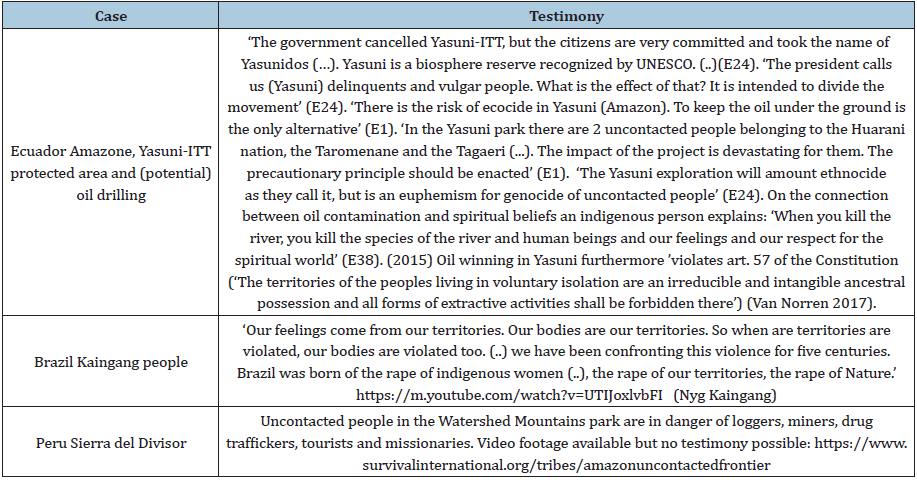

Buen Vivir became increasingly prominent in the region in the wake of political debates at the beginning of the 21st century, in particular its inclusion in constitutional discussions in two Andean countries: Ecuador and Bolivia (where they use the terminology ‘Vivir Bien’). Buen Vivir is also linked to the recognition of indigenous wisdom and indigenous territories administered by indigenous justice [17,50], as well as the creation of a framework for the rights of Nature. Ecuador was the first country in the world to recognize the rights of Nature at the constitutional level in 2008 [8]. This concurs with Western (European) debates on ecocide [51] happiness and well-being, [52,53] (Table 4), and the critique of economic growth that sometimes draws on the spiritualities and worldviews of indigenous communities such as the degrowth movement [54].15 From this perspective emerges a very different conservation principle, since conservation dissociates culture from Nature, which are one in the indigenous mind. Therefore, conventional conservation is seen as an intolerable separation human rights, social-economic rights and Nature rights [8]. The purpose of life is living in harmony with Nature, thus increasing biodiversity. The Buen Vivir economy offers different economic principles to achieve this, including food and energy sovereignty [43]. It expresses itself also in indigenous landscape management, agricultural practices - like mixed cropping agriculture, as well as addressing many different ecological levels in the Andes to mitigate risks and avoid ecological degradation - different property (and exchange) relations and relations of mutual support, as well as ‘planes de vida’ (life plans, respecting Nature, culture and territories) [17,55]. Ecuador adheres to the third conceptualization of conservation as described above, but the government of President Correa politicized the judiciary in such a way that rights of Nature were often ignored [29]. Interestingly his more conservative successor restored the independence of the courts, leading to more judgements in favor of Nature and jeopardizing his mining plans. Though Ecuador has both conventional protected areas and protected areas in which humans can live (often uncontacted forest people, see below), the protected areas sometimes are also under threat. In the case of uncontacted people this poses an extra challenge, as one does not only need to speak on behalf of Nature but also on behalf of people who have not been in contact with global civilization. This is what happened in the case of Yasuni-ITT (Amazone), which provoked a movement both inside and outside Ecuador, when the Correa government announced possible oil drilling [56]. Testimonies from communities in Latin America on conservation gone wrong are given in (Table 5).

Table 4: Examples of western initiatives on wellbeing and happiness.

Table 5: Case Ecuador, Brazil and Peru.

Foot Note

15 For source material see also Research & Degrowth, an academic association: http://degrowth.viper.ecobytes.net/

Uncontacted Indigenous Peoples Living in

Harmony with Nature

Conservation should also take into account the wish of uncontacted indigenous people to remain uncontacted and living in isolation, in harmony with their natural environment. An example of failed conservation is, according to survival international, the Sierra del Divisor (Watershed Mountains) park in Peru, at the border with Brazil. The park, which was created in 2015, is still open to loggers, drug traffickers and miners as well as to possible future oil exploration (large areas of the park have not been exempted). It thus failed to protect the uncontacted people who live there, who are ironically also the best conservationists having thorough knowledge of the ecosystems [57]. Furthermore, tourists, some academics and missionary can pose a threat. Indigenous people often do not survive on first contact, due to amongst other unknown diseases. ‘On the very rare occasions when they are seen or encountered, they make it clear they want to be left alone’ [58].

The Way Forward: Convivial Conservation & Convergence with the Three Cosmovisions

An interview with Bram Büscher states: ‘There are major heated debates taking place regarding the course of environmental conservation. For example, biologist E.O. Wilson, believes that half of the Earth must consist of unspoilt natural areas, in order to protect the foundations of life on the planet. Other than being financeable difficult to achieve, it threatens to endanger many indigenous lifestyles. In contrast, Büscher believes that we should ultimately move away from protected nature reserves. ‘Environmental conservation was created as a response to the destruction of nature and the environment. Particularly in the last 30 years, many protected nature reserves have been added to the list. The more nature we lose, the more nature we try to protect,” says Büscher. Unfortunately, this does not end the loss of biodiversity. As such, Büscher is advocating a different approach. “We need to move towards a promoted rather than protected nature, where people live alongside nature in a better way. We call this convivial conservation.” Convivial comes from the Latin “con vivire”; the need, according to Büscher, for humans to coexist with all life on earth’ [59]. The proposal of convivial conservation is a more integral idea on how to deal with conservation and biodiversity. It refers to both alternative Western theories and indigenous philosophies of wellbeing such as on the one hand degrowth, the doughnut economy of Kate Raworth [60], climate justice and rapid ecological democracy and on the other hand indigenous Buen Vivir and the ICCA coalition. To this one can add African Ubuntu and Buddhist Happiness which refers to living in respect for all sentient beings, as well as for example indigenous practices from Australia and New Zealand, which granted legal personhood to two Nature entities such as a river [61,62]. It means that also for non-indigenous people it is imperative to find lifestyles that are more in harmony with Nature, which reduces the need for strict conservation areas. In an ideal world human life would increase biodiversity and not decrease it. Some authors allege that biodiversity increased with indigenous or convivial land management [63]. In this sense, the proposal of conviviality requires ‘going beyond protected areas as the main form of conservation governance, to prioritize developing integrated spaces within which humans and other species can continue or learn to co-exist respectfully and equitability. This does not mean humans and wildlife must always occupy the same spaces. Rather, conviviality may require some species respectfully to avoid one another, depending on needs and temperament (which already happens in many places, and has indeed long been part of the human-nonhuman relations of many Indigenous and other traditional peoples). Conviviality also requires equity among the different people involved in conservation, and the inclusion of diverse landscapes and governance systems within the conservation matrix, including agroecological systems and other spaces in which humans pursue sustainable livelihoods.’ [1]. In summary we can say that Buen Vivir in Ecuador adheres to the third conceptualization of conservation (convivial) but has been hampered by politicized implementation under the Correa government. Bhutan adheres to a mixture of conceptualization one (mainstream, in practice) and three (convivial): in GNH theory culture takes prevalence but traditional commons have largely been abolished. Therefore, there is a tension between modern implementation of strict conservation (based on cultural beliefs) and traditional practices. However, since population density is not high problems mainly occur from too much wilderness and wildlife hampering farmers, especially since increased migration to cities is taking place. This seems to immediately discredit conceptualization two that contends there is no such thing as wilderness anymore. This proposition counts for more populated geographical areas. South Africa adheres to conceptualization one (mainstream) but is under criticism from local communities for example in mining projects, demanding respect for their cultural rights including ancestor worshipping, which is tied to the land.

Concluding Remarks

In this article we have tried to argue in favor of indigenous conservation practices, which in our view should get priority over conventional western conservation practices. Not only from a point of view of respecting basic human rights, cultural rights and socioeconomic living conditions of communities concerned, having regard to the 2007 UNDRIP principles, but also because these practices advance the most effective, locally driven solutions for biodiversity and ecosystem preservation, respecting Mother Earth. The principles for ‘çonservation’ ought to be biocentric instead of anthropocentric, centering around Earth governance and living in harmony with Nature. For indigenous and other territory bound communities these are summarized as ICCA’s or OECM. The parties to CBD should give utmost importance to those when reviewing the 30 by (20)30 conservation proposal in 2022. We have discussed a number of them, with specific reference to African Ubuntu, Buddhist Happiness and a detailed account of Buen Vivir of the Andes people. It is not sufficient to simply recognize these alternative systems, but it is imperative to actively promote and empower these ways of life, and also to explore how the examples from the global South may be included in the mainstream system or change the mainstream system. As we have seen, organizations like WWF do recognize the need to respect indigenous ways of life, be it explicitly only since 2008, but the reality on the ground is unruly and often leads to vehement protests of local communities. Too often indigenous ways of life are disrupted to give way for modern development. As long as the development model does not change, the traditional biocentric ways of life are in danger of dying out; and thus conventional conservation will be in need of increasing to offset anthropocentric lifestyles. However well-intended, frameworks such as the CBD and SDGs are still resting on outdated development models that need to be made ‘sustainable’ instead of rethinking these models into wellbeing including all communities of life. We have given a number of examples of Global South practices and life philosophies respecting biodiversity and harmony with Nature that have been ignored so far by mainstream development science, viewing these as romantic left-overs from the past that are bound to disappear in the ‘natural’ evolution towards modern society. The latter may be true, but the question is: is humanity better off? The rest of (nonhuman) life already knows (experiences) the answer.

References

- Fletcher R, Massarella k, Kothari A, Das P, Dutta A (2020) A New Future for Conservation. Progressive International Blueprint.

- Judith S, Julie GZ, Constance F, Bhaskar V, Piero V, et al. (2019) Protecting Half of the Planet could Directly Affect over One Billion People. Nat Sustainability 1094- 1096.

- WWF International (2008) Indigenous Peoples and Conservation: WWF Statement of Principles. Gland (Switzerland): WWF International.

- Worren T, Baker KJM (2019) WWF Funds Guards Who Have Tortured and Killed People. Buzzfeed News.

- Mukpo A (2021) As COP15 approaches, ’30 by 30’ becomes a conservation battleground. Mongabay.

- Mukpo A (2020) Report: WWF knew about rights abuses by park rangers but didn’t respond effectively.” Mongabay.

- Advisory Council for International Affairs (AIV) (2011) The Post-2015 Development Agenda: The Millennium Development Goals in Perspective. Advisory report 74 The Hague: AIV.

- Van NDE (2017) Development as Service, a Happiness, Ubuntu, and Buen Vivir Interdisciplinary View of the Sustainable Development Goals. Tilburg University Tilburg the Netherlands.

- Shanahan M (2021) Will 30×30 reboot conservation or entrench old problems? The Third Pole.

- Harrop SR (2011) Living in Harmony with Nature? Outcomes of the 2010 Nagoya Conference of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Journal of Environmental Law 23(1):117-128.

- CBD (2018) Long-Term Strategic Directions to the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity, Approaches to Living in Harmony with Nature, and Preparation for the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. CBD.

- Michelle L (2021) Biodiversity 2050: Can the Convention on Biological Diversity Deliver a World Living in Harmony with Nature? Yearbook of International Environmental Law 30(1): 79–101.

- Rainforest Foundation UK (2020) Press release: UN 2030 conservation plan could dispossess 300 million people. UK: Rainforest Foundation.

- Wilson EO (2016) Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

- Worsdell, Kumar T, Kundan A, James RG, Gwili EMW, et al. (2020) Rights-Based Conservation: The path to preserving Earth’s biological and cultural diversity? Washington DC (USA): Rights and Resources Initiative.

- Borrini FG, Farvar MT (2019) 66. ICCA. Terriotiros de vida.” In Kothari, A. Salleh, A. Escobar, A. Demaria, F. Acosta, A. (eds.) Pluriverso: Un diccionario del posdesarrollo. Barcelona: Icaria Antrazyt Decrecimiento.

- López P (2015) Territorios y áreas conservadas por pueblos indígenas en la región Andina Amazó

- Borrini G (2010) Bio-Cultural Diversity Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Examples and Analysis. IUCN.

- FAO, FILAC (2021) Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. an Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the Caribbean. FAO.

- Mukpo A (2021b) The Brooklyn bridge needs a makeover but is rainforest lumber still in style? Mongabay.

- Ntibagirirwa, Symphorien (2012) Philosophical Premises for African Economic Development: Sen’s Capability Approach.

- Metz T (2007) Toward an African Moral Theory. Journal of Political Philosophy 15 (3): 321-241.

- Ramose MB (1999) 2005 revision. African Philosophy through Ubuntu. Harare, Zimbabwe: Mond Books.

- Eze MO (2010) Intellectual History of Contemporary South Africa, Chapters 6-9. New York: Palgrave McMillan, St Martin’s Press.

- Gade CBN (2012) What is Ubuntu? Different Interpretations among South Africans of African Descent. South African Journal of Philosophy 31 (3): 484-503.

- Metz T, Gaie JBR (2010) The African Ethic of Ubuntu/Botho: Implications for Research on Morality. Journal of Moral Education 39 (3): 273-290.

- Mbiti JS (1990) African Religions and Philosophy. 2nd ed. Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers (first published 1969).

- Van NDE (2014) The Nexus Between Ubuntu and Global Public Goods: Its Relevance for the Post 2015 Development Agenda. Development Studies Research 1(1): 255-266.

- Van NDE (2019) The right to Happiness in three traditions of the Global South. Revue Juridique du Bonheur 2019, chapter 8. Observatoire International du Bonheur (OIB) France.

- Van NDE (2017) The Sustainable Development Goals viewed through Gross National Happiness, Ubuntu, and Buen Vivir. International Environmental Agreements 431-458.

- Government of South Africa (2007) Batho Pele Handbook. A Service Delivery Improvement Guide. Pretoria: Department of Public Service and Administration (DPSA).

- Clarke John (2015) Wild Coast Mining Conflict: Xolobeni Escalates. Daily Maverick.

- Kumleben N (2021) South Africa’s Coal Deal Is a New Model for Climate Progress. The agreement is the most Impressive Thing to Come out of the COP26 Climate Summit. Foreign Policy.

- Ura K, Alkire S, Zangmo T, Wangdi K (2012) A Short Guide to Gross National Happiness Index. Thimphu, Bhutan: The Center of Bhutan Studies.

- Ura K, Galay K (2004) Gross National Happiness and Development (Proceedings of the First International Seminar on Operationalization of Gross National Happiness). Thimphu: Center of Bhutan Studies.

- Phuntsho K (2013) The History of Bhutan. London: Haus Publishing.

- Tideman SG (2004) Gross National Happiness: Towards a New Paradigm in Economics.

- Government of Bhutan (2018) Twelfth Five Year Plan 2018-2023. Thimphu (Bhutan): GoB.

- Gyem T, Tshering S, Pema K (2013) GNH- Ecological Diversity and Resilience”. Indo-Bhutan International Conference on Gross National Happiness 2: 309-313.

- Allison, Elizabeth (2005) Gross National Happiness and Biodiversity Conservation in Bhutan. Paper presented at the First International Conference on Gross National Happiness. Proceedings Thimphu: CBS: 1162-1178.

- Zurick D (2006) Gross National Happiness and Environmental Status in Bhutan. Geographical Review 96(4): 657-681.

- Sousa SB (2008) Las Paradojas De Nuestro Tiempo Y La Plurinacionalidad. Montecristi, Manabí, Ecuador: Asamblea Constituyente.

- Acosta A (2015) Buen Vivir Vom Recht auf ein gutes Leben. München, Deutschland: Oekom Verlag.

- Gudynas Eduardo (2009) La Ecología Política Del Giro Biocéntrico En La Nueva Constitución De Ecuador. Revista de Estudios Sociales 32: 34-47.

- Hidalgo CAL, Cubillo APG (2014) Six Open Debates on Sumak Kawsay. ICONOS 48: 25-40.

- Villalba U (2013) Buen Vivir vs Development: a Paradigm Shift in the Andes? Third World Quarterly 34 (8): 1427-1442.

- Thomson B (2011) Pachakuti: Indigenous Perspectives, Buen Vivir, Sumaq Kawsay and Degrowth. Development 54(4): 448-454.

- Latour B (2017) Facing Gaia. Eight Lectures on the New Climate Regime. Polity Press.

- Hernandez G, Laats H (2020) Buen Vivir: A Concept on the Rise in Europe? Green European Journal.

- Yupangui, Verónica MY (2015) Pautas Para El Ejercicio De La Justicia Indí Ecuador: INREDH.

- Gauger A, Pouye RFM, Kulbicki L, Short D, Higgins P (2012) The Ecocide Project: Ecocide is the Missing 5th Crime Against Peace. London: Human Rights Consortium.

- Revkin AC (2005) A New Measure of Well-Being from a Happy Little Kingdom. New York Times.

- Royal Government of Bhutan (2012a) The Report of the High-Level Meeting on Wellbeing and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm. New York: The Permanent Mission of the Kingdom of Bhutan to the United Nations. Thimphu: Office of the Prime Minister.

- Alisa DG, Demaria F, Kallis G (2015) Degrowth, A Vocabulary for a New Era. New York and London: Routledge.

- Laats H (2005) Hybrid Forms of Conflict Management and Social Learning in the Department of Cusco, Peru. Ph.D. Thesis. Wageningen University.

- Global Alliance (2014) Verdict of the Rights of Nature Ethics Tribunal, Yasuni Case, Preamble.

- Survival International (2022) Sierra del Divisor, the Watershed Mountains, Survival.

- Survival International (2021) The Uncontacted Frontier. Survival.

- Wageningen University Research (2020) Coexisting with Nature. Interview with Bram Bü

- Raworth K (2018) Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. UK: Cornerstone.

- Catherine JIM (2015) Nature as an Ancestor: Two Examples of Legal Personality for Nature in New Zealand. Vertigo, Revue électronique en sciences de lenvironnement (22).

- Kauffman CM, Martin PL (2021) The Politics of Rights of Nature. Strategies for Building a more Sustainable Future. MIT Press.

- Dunbar OR (2014) An Indigenous Peoples History of the United States. Boston (USA): Beacon Press.

- Kate M, Anja N, Robert F, Bram B, Wilhelm A (2021) Transformation Beyond Conservation: How Critical Social Science can Contribute to a Radical New Agenda in Biodiversity Conservation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 49: 79-87.

- Nair N (2016) How will the Age of Anthropocene fare for Bhutan? Kuensel online.

- Survival International (2017) India, Tribe Faces Eviction from Tiger Reserve – but Uranium Exploration Approved. Survival.

- Swati V (2015) Project Tiger may evict Chenchus, The Hindu.

© 2022 Dorine Van Norren. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)