- Submissions

Full Text

Biodiversity Online J

Assessment of Pesticide Use against Tephrtidae Fruit Fly and other Pest Among Small-Scale Solanaceous Vegetable Farmers in Bugorhe-Kabare the Democratic Republic of Congo

Jean ARK1*, Jean BMB2

1Agricultural Entomology laboratory, Entomology Section, Research Centre in Natural Sciences (CRSN-Lwiro), Congo

2Department of Biology, State University of Bukavu, Congo

*Corresponding author: Jean Augustin Rubabura Kituta. Agricultural Entomology laboratory, Entomology Section, Research Centre in Natural Sciences (CRSN-Lwiro) - PO : D.S. / Bukavu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo

Submission: February 23, 2022; Published: March 31, 2022

ISSN 2637-7082Volume2 Issue2

Abstract

India is a country of diverse cultures due to the influence of geography, climate and biodiversity. The current state of the developing world is the result of this process of evolution and experimentation. As Indian agriculture was later considered to be the backbone of the Indian economy, the contribution of agribusinesses to India’s national income increased even more. Science and Technology has always being the tool for advance agricultural practices and India is way ahead in applying the same to rise as a largest economy. FAO recognized the contribution of India as a third largest economy in the world after US and China however also concern about the food shortage and malnutrition. The increasing feminization of agriculture is mainly related to the migration of men from rural to urban areas and other domestic issues. To address the issues, a model is proposed for rural India for integrated agriculture based approach with involvement of every household from a small village to cater the need of food and livelihood thereby also progressing in further development for a better life.

Introduction

Different types of insect pests afflict production in western Albertan Rift area [1,2]. Tephritid fruit flies such as Dacus bivittatus (Bigot), Dacus punctatifrons Karsch, Batrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (syn. B. invadens [Drew, Tsuruta & White]), Bactrocera latifrons (Hendel), Ceratitis cosyra (Walker), Ceratitis rosa Karsch, Ceratitis fasciventris Bezzi, Ceratitis capitate (Wiedemann), Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett) and other pests such as Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Noctuidae), Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Gelechiidae), Anarsia lineatella Zeller (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae), Comstockaspis perniciosus (Comstock) (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) constitute a major constraint to increased production of fruits and vegetables in orchards and gardens [3-7] and those small-scale farmers has a lack of fundamental horticultural knowledge [8]. For example, fruit damage due to the native tephritid fruit fly species was already high, causing serious problems to growers. However, this situation was exacerbated with the invasion of B. dorsalis, with damage frequently reaching 100% in the absence of effective pest management [9,10]. This highly invasive species has since displaced local fruit fly species from smallholder crops [9]. Even today, [11] show that, despite the advances in agricultural sciences, losses due to pests and diseases range from 10 to 90%, with an average of 35-40%, for all potential food and fiber crops. The relative economic impact is perhaps strongest felt by smallholder farming families that count on the small-scale sales of high-value crops significantly to contribute to the family economics. The enormous losses they cause through direct damage to fruit, vegetables, and loss of market opportunities. Further, competitive release implies the need for a combination of lures and methods. These observations are important for developing control schemes tailored for smallholder settings. Pest management and control strategies should thus be amenable to both large-scale productions and small-scale farming, with emphasis on the latter [12]. Pesticides are agricultural technologies that enable farmers to control pests and weeds and constitute an important input when producing a crop. Promoting sustainability in agricultural production requires critical consideration of agricultural technologies and identification of best practices [13,14]. Several authors [15,16] demonstrated that agro-pesticide technologies, including insecticides, fungicides and herbicides, formed one of the driving forces behind the Green Revolution. In fact, coupled with high-yielding crop varieties and increased land for crop production, significant yield improvements were achieved. However, this was realized at the expense of the natural environment and the health of farmers. The unsafe use of pesticides is common in developing countries is shown in different studies conducted on knowledge, attitude and behavior among smallholders [11, 17]. Tephritid flies attack a large variety of fruits, which constitute highly priced commodities in many countries. Insecticides have been used extensively for their control. Although resistance development in fruit flies has not kept pace with that in other insects, possibly due to their high mobility and tendency for wide spatial dispersal, recent studies have indicated that selection pressure has now reached the point where resistance is detectable in the field and control may therefore become problematic [18]. Moreover, requirement of pesticides in vegetables is comparatively higher than the other food products [19] in Bugorhe area at Kabare, South Kivu province. Bugorhe area is one of the major suppliers of vegetables in the Bukavu town. However, the sharp increase in the urban population of Bukavu town poses several challenges, including food security (supplying these cities with food), job creation and income generation [20, 21]. In order to meet these challenges, poor families in cities resort to market gardening [21,22]. These market garden centers generally exploit fruit vegetables (tomato, chilli, pepper, eggplant, okra, and watermelon), tubers / bulb (carrot, onion) and some exotic leafy vegetables (scallions, leek). Indeed, [10] reported that a lack of IPM research relevant to small farms is perhaps a more serious problem than the provision of advisory services. Again, market garden smallholders have a lot of difficult to get chemical pesticides, traps, lures and food baits, lack of IPM method and IPM experts, lack of knowledge on the use and consequences of chemical pesticides and lack of packaging management. Those market garden smallholders saw and know fruit flies and other pest at solanaceous crop. In addition, the market garden smallholders do not know the good way to use chemical pesticides and traps such as lures as well as food bait are not sold in the east of the DRC in general and in South Kivu in particular. Relatively no research has been conducted on the use of pesticides on market garden such as solanaceous crop in study area. However, this study assesses the pesticides use: farmer’s practices, their knowledge and perceptions regarding the uses of chemical pesticides in study area. This paper reports findings on practices and use of pesticides in control of tephritidae flies and other pests by small-scale vegetable farmers in Bugorhe-Kabare area at the western of Albertan Rift area.

Materials and Methods

The study consisted of interviews with farmers and farm workers in rural areas in Bugorhe- Kabare area, where horticultural crops (vegetables, flowers, fruits) were mostly cultivated using farm inputs, particularly pesticides. It was carried out in Bugorhe area, which is located at the Kabare territory (Latitude: 2° 30′ and 2° 50′S, Longitude: 28° 45′ and 28° 55′E, Southwestern of the Kivu Lake) at the South Kivu province, eastern part of DR Congo. It is peripheral to the Kahuzi-Bièga National Park is located in the community Kabare chiefdom in South Kivu Province and inhabited by the Bashi ethnic group [23]. The survey covered the period from January 01 to March 28; 2021.Simple random sampling was used to select the sample from the population. This is the least biased technique and also gives every element an equal chance for selection during the study [24] and some criteria were followed by the quota method [25,26]: being market gardeners (tomato, pepper, eggplant and pepper) and/or sellers of phytosanitary products and in one of the localities of the Bugorhe group, 12 market gardeners of these solanaceous and sellers of phytosanitary products of male and female sexes combined and chosen by locality, the freedom of choice left to the investigator. The sample size is 96 market gardeners. Research instruments include reconnaissance survey, interview questionnaire pre-test, household interview and field survey, smallholder vegetables and focus group discussions. The semi-structured type of questionnaire considering the purposed of study is to assess the pesticides use, farmer’s practices, their knowledge and perceptions regarding the uses of pesticides. These include the socio professional characteristic of small-scale solanaceous vegetable farmers, crop production, main market gardeners’ crops used, types of pesticides, WHO Hazard Class and health effects (2005), pesticide application, pesticide mixtures used, trend in pesticide use, reasons given for the trends in pesticide use, perception of pesticide poisoning symptoms, system of pesticide packaging management. Data was obtained from primary and secondary sources. However, a questionnaire composed of semistructured items was designed based on the published literature on the subject as well as the authors’ experiences in the field. Data was collected through an agricultural survey through face-toface interviews with farmers or farm workers during agricultural activities. Indeed, the questionnaire was designed in French and translated into Kiswahili (the national language). The former is understood by the majority of farmers and pre-tested with small samples of farmers in the same areas before using it in this study. The survey data were been encoded in Microsoft Office Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and R software (R Core Team, 2018) were analyzed. Two-way ANOVA was used at the significant level of 1%. The Tukey multiple comparison was been used too at the confidence level of 95%. Before the variance analyze application, normality verification of data distribution hypothesis was been done by the Bartlett’s K-squared test and the descriptive result was expressed by percentage.

Results

a. Socio Professional characteristic: The majority of farmers were male (79.17%) with an average age of 30, ranging from 30 to 60, reported the use of different pesticides in more vegetable farms in Bughore-Kabare zone. According to their level of education, 46.87% of these men attended primary school and 36.46% secondary school and 16% university, while 63.54% of them did not have agricultural training and 36.46% are trained in agriculture

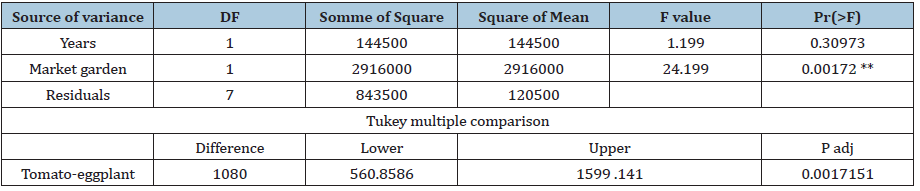

b. Solanaceous output in study area during the period of 2017 to 2021: The mean of tomato (5780kg±471.17) differed to the mean of eggplant (4700kg±158.11). Le table 1 presented the ANOVA summary of solanaceous output in study area during the period of 2017 to 2021. The table shows a significant difference between the outputs of market garden crop (Table 1). In case of years, there is not difference, i.e., during the five years solanaceous products were the same with an high tomato output.

Table 1: ANOVA summary of solanaceous products.

c. Main market gardeners’ crops used: The main cultivated

solanaceous crops grown in the Bughore area is tomato

(Lycopersicon esculantum) at 47.92% followed by eggplant

(Solanum melongena) at 36.46%, pepper (Capsicum frutescens)

at 10% and pepper (Capsicum annum) at 5.21%. Every farmer has

a reason to choose vegetable crops, one for their easy-to-practice

short-cycle crops, and another for their short-term profitable

investment, and the last for their very high market value crops per

unit area.

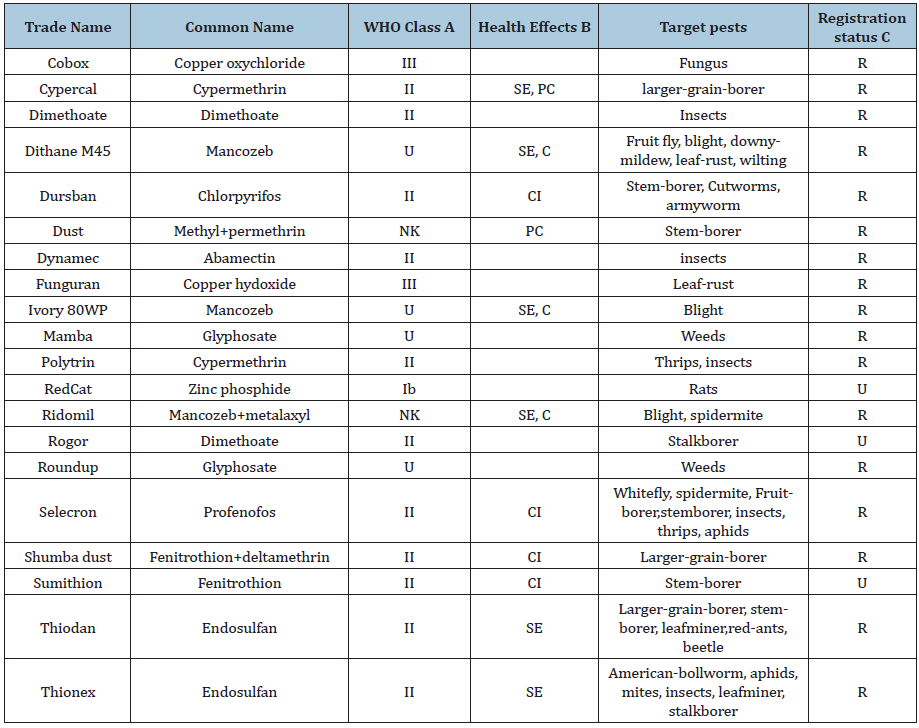

d. Types of pesticides: Farmers in the Bughore-Kabare

region most often use insecticides (44.79%) and fungicides

(43.75%) but also 4.17% herbicides and 7.29% rodenticides due

to the production of tomatoes, eggplants, peppers and peppers

and other vegetables. The type and number of pesticides used

in different crops depended on the pest population and their

potential damage to the crop as well as farmers’ perception of pest

management practices (Table 2). Additionally, pesticides were

supplied in containers ranging from 0.5 liters to 5 liters or in packs

ranging from 0.5 kilograms to 25 kilograms. In most cases, a liter

and a kilogram were common, as well as the distribution of small

quantities by vendors. The table 1 of types of pesticides used in

small-scale vegetable farms in Bughore area classified using the

WHO Hazard Class and health effects, 2005. In the Bughore-Kabare

area, of the Class II (moderately hazardous), III (slightly hazardous)

or U (unlikely to present an acute hazard) insecticides and

fungicides registered in use, 20% contained chemicals suspected

of being endocrine disruptors, 40% were cholinesterase inhibitors

and 35% each were carcinogenic and potentially carcinogenic.

Many end-of-use pesticides were not registered for general use.

Carbofuran, a nematicide, zinc phosphide, a rodenticide, and

methomyl, an insecticide, were the only WHO class Ib (highly

hazardous) not used. However, the insecticides used included

pyrethroids (such as cypermethrin, deltamethrin, permethrin,

acelamectin (abamectin, abactin and acetamiprid) and lamdacyhalothrin);

organophosphates (such as pirimiphos-methyl,

profenofos, chlorpyrifos, dichlorvos, fenitrothion), dimethoate and

carbamates (carbofuran) and dithiocarbamates (Glucocorticoids).

The most popular fungicides were copper-based such as copper

oxychloride, copper hydrochloride, and copper sulfate, although

metalaxyl-M, zinc, manganese, and mancozeb were also used

Table 2: WHO hazard class and health effects, 2005.

e. Pesticide application and mixtures used: More than

50% of farmers applied pesticides using knapsack sprayers up

to once a week depending on the type of vegetable crop. Twentyeight

point zero four percent of farmers reported two pesticide

applications and five times (10.42%) and six times (7.29%) per

week, i.e., routine pesticide applications. The majority of farmers

applied pesticides once a week. The fact that pesticides are more

expensive and use cultural control methods and occasionally

botanical pesticides. More farmers surveyed applied mixtures

of pesticides. Reported pesticide mixtures included fungicide +

insecticide (Dithane M45 and Ascozeb 80WP) reapplied to onions

and tomatoes, Maneb and Rocket EC to tomatoes, onions and

cabbage. In addition, other pesticide mixtures are two fungicides +

insecticide (Dithane M45, Ascozeb 80WP and Ivory 80WP) applied

on onions, cabbages and tomatoes, two insecticides (Thiodan and

Rocket EC) used on tomatoes and eggplant, insecticide + fungicide

(Thiodan and Dithane M45) applied to onions, cabbage, eggplant

and tomatoes. These farmers apply pesticides in mixtures. There

were combinations of up to two pesticides in a single tank mix. Up

to 90% had up to three pesticides in a mixture. Either farmers had

no specific instructions from the label or extension staff regarding

these tanks mixes.

f. Trend and reasons given for the trends in pesticide use:

62.5% of farmers who responded to the trend in pesticide use

over the past 3 years said the trend was increasing, while 20.83%

thought it was constant and 16.67% thought it was decreasing.

The trend of pesticide use over the past 3 years in Bughore-Kabare

region is on the rise as they farm in relatively similar environments

and international organizations have started assisting them with

agricultural inputs such as vegetable seeds. With the increase

in the use of pesticides, there is also a decrease in bees observed

by farmers in the environment of the study area. The reasons for

increasing trends in pesticide use are ineffective pesticides, pest

resistance, increasing insect damage, pest population, agricultural

area, insect pests, plants and number of pests. The constant ones

are that the pesticides are effective, same area, same farm size,

correct instructions and effective pesticides, less pests, drought and

even farm, same application everywhere and same pesticides used

and the reasons for the tendency to the downside are heavy rains,

unavailability of pesticides, price increase, less harvest, drought,

good farm preparation and reduced agricultural area.

g. Perception of pesticide poisoning symptoms: Hundred

percent of farmers reported feeling sick after routine application of

chemical pesticides in the study area. However, the most common

symptoms reported and included skin effects (37.5%), neurological

system disorders (headache, dizziness) were (20.83%).

Additionally, farmers reported suffering from sneezing (6.25%),

excessive sweating (5.21%), coughing and poor vision (3.12%),

nausea (2.08%) and stomach pain (1.04%). Therefore, skin effects,

headaches and dizziness are dominant in the Bughore-Kabare

region.

h. System of pesticide packaging management: Sixty-two

point five percent of the farmers answered that the management

system for pesticide containers is to leave them and keep them on

the stakes and/or sticks in the field, while 20.83% buried them and

16.67% burned them. Pesticide packaging management system

used by farmers is stake and/or stick in field in Bughore-Kabare

area as they have no training in pesticide use, water pollution water,

air, soil and living beings hence the problem of poisoning in the

environment.

Discussion

The majority farmers were males in more farms of market gardeners at the Bughore-Kabare area, eastern of DR. Congo. [27] and [28] reported that a small percentage of women (8% - 28%) are involved in market gardening in Togo too. The low involvement of women in the production of fruit vegetables (tomato, eggplant and pepper) could be explained in the fact of that, women are generally not empowered to apply the phytosanitary treatment required by these crops [20]. Indeed, the phytosanitary treatment is tedious (acquiring the product, preparing the solution and applying it using a sprayer), and complicated for the uninitiated who constitute a large proportion of peasant women. Our result joined the results of [27] and [29], the market gardeners farm carried on through no employment and/or no decent salary with a level of primary and secondary school. His reasons for choosing vegetable crops one of them for their short-cycle, easy-to-practice crops, another group for their short-term profitable investment and the last group for their crops with very high market value per unit area. This may be explained the important income generation and job creation [27,28] and in order to meet these challenges, poor families in cities resort to urban and peri-urban agriculture, in particular market gardening [27,28,30] reported similar result; the farmers assume that the only solution to pest problems is to spray more frequently and using different types of pesticides. However, [31] revealed that farmers were not receiving agricultural extension service hence have attempted various means especially in pesticides use when dealing with pest problems but were constrained by the lack of appropriate knowledge.

A lot of out of pesticides are unregistered for general use. [32] reported similar result in African countries and worrying risk values for the exposure of market gardeners to pirimicarb and Chlorpyrifos-methyl, thus reflecting a risk to the health of market gardeners. Given the large number of pesticides used and the frequency of application (very high risk of bioaccumulation of pesticides). It is important to note that chemical pesticides are toxic and their use cannot be accepted or encouraged unless the methods of use are perfectly mastered as well as the risks to human health and the natural environments likely to be affected [33,34]. WHO surveys have found that African countries import less than 10% of the pesticides used in the world, yet they account for half of accidental poisonings and more than 75% of fatal cases [35]. Although fungicides are not easily observed to cause serious and acute damage to farmer’s health, they have been reported to cause some harm to farmer’s skin and eyes [36]. It is also reported that there is a long-term risk for cancer development and endocrine disruption resulting from farmer’s exposure to fungicides containing Mancozeb [36]. WHO Class Ib (highly hazardous) are not recorded in use. This pesticide can be fatal if inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the skin, even though the effects of contacts and/ or inhalation may be delayed due to its formulation [37]. The effects of exposure even of a short duration can be delayed but there is a possibility of cumulative effects [38]. Usually amounts and types of pesticides used have been reported by [39] to show important differences among countries and among regions within one country depending on the type of agricultural production and level of economic development. More of farmers applied pesticide once a week. The fact that pesticides are more expensive and use some cultural control methods and occasionally botanical pesticides [40-42] reported that there is a need to bring to the attention of these farmers existing alternative pest management strategies that are cost effective and environmentally friendly. In Zimbabwe, although small-scale vegetable farmers use some cultural control methods and occasionally botanical pesticides, pest control is predominantly by the use of synthetic pesticides. Farmers did not have specific instructions either from the label or from extension staff regarding these tank mixtures. [43] in Benin, [44] in Tunisia and [45]in Birmania (Myanmar) reported the similar results. The tank mixture of pesticides observed in this study indicates that farmers lack basic knowledge of pesticides. [46] observed that there was an interaction between fungicides, insecticides and water mineral content that influenced the efficacy of individual pesticide against fungal pathogens and insect mortality and some tank mixtures induced phytotoxicity on tomato. There is limited information on the reaction and effects of the mixtures observed in this study. According [47], the total exposure to the chemical is the sum of exposure during pesticide storing, mixing, applying and disposing of the chemicals. As a result, and coupled with lack of basic knowledge of pesticides, farmers’ decisions on what pesticides and how to use do not have a bearing on health or safety of the environment. The risk of long-term effects of the pesticides that were been used in the study area is high especially due to exposure to carcinogens, possible carcinogens and suspected endocrine disruptors. The pesticides were been mixed wrongly, mishandled and misused [39]. The farmers used more pesticides because they based the applications on calendar spray pesticides program without necessarily giving much priority to health and environmental considerations [48].

The trend of pesticide use over the past 3 years in Bughore- Kabare region is on the rise as they farm in relatively similar environments and international organizations have started assisting them with agricultural inputs such as vegetable seeds. With the increase in the use of pesticides, there is also a decrease in bees observed by farmers in the environment of the study area. In African countries, many government extension programs encourage the use of pesticides, but do not consider their effects in the environment and health risks [49]. This is a typical situation in many developing countries where the choice of pesticides to be used by farmers influenced by the suppliers [48]. The pesticide have a skin effects, headaches and dizziness, neurological system disorders (headache, dizziness), sneezing, excessive sweating, coughing and poor vision, nausea and stomach pain in the Bughore- Kabare region. The three routes of exposure to pesticides: dermal, respiratory and oral [50]. Usually, farmers assume that pesticides poisoning symptoms are normal so they get used to them [51]. Almost 750,000 people contract a chronic disease such as cancer each year because of exposure to pesticides, nerve damage, infertility and deformities, etc. In addition, although developing countries only employ 20% of all chemicals used in agriculture globally, they still account for more than 99% of deaths worldwide because of human poisoning pesticides [35]. The studies carried out in Indonesia [51] and in Ivory Coast [52] reported that pesticide applicators tended to accept a certain level of illness as an expected and normal part of the work of farming and, do not report the symptoms in official health centres for formal medical assistance. These pesticides are inhaled through different routes via; oral (through the mouth and digestive system), dermal (through the skin), ocularly (through eyes) or by inhalation (through the nose and respiratory system). The pesticides have effect on the decline of biodiversity by indirect effect to the non-target organisms [53]. The pesticide packaging management system used by farmers is stake and/or stick in field in Bughore-Kabare area as they have no training in pesticide use, water pollution water, air, soil and living beings hence the problem of poisoning in the environment. Our result is similarly to [54]. The abandonment of packaging in the field poses a great danger to children and the uninitiated who may use it as second-use packaging and containers. Incineration of packaging (including pesticide waste and contaminated materials) is also not a good practice because during combustion, some pesticides produce highly toxic fumes which inhalation and / or contact are harmful to the human body and animals [54]. Likewise, the author points out that the burying of packaging (practiced by 6% of respondents in this study), residues and waste of pesticides presents the risk of contamination of groundwater. Pesticide packaging is generally abandoned in the field or incinerated as initially observed in other African countries [55,56]. According to [21], Nkolo area in west of DR Congo and its surroundings, the market garden fields being mainly installed along waterways for watering facilities, part of the packaging abandoned in the field ends up in the course of water carried by strong winds or runoff. The same is true for pesticides accumulated in the soil, which, after heavy rains, carried in the runoff to the rivers and volatile particles during the treatment, some of which are deposited directly in the rivers. At the end of the treatment, the market gardeners wash and wash their clothes in the streams. Contamination of waterways with pesticides is therefore not excluded in the study area, even though most market gardeners claim to maintain sprayers in the field so as not to pollute the waterways. Our result is in the same way to result of [57]. The result is in the same way with of the [21]. Good management use and proper disposal of agrochemicals is an important health and environmental issues in the developing countries [57,58] reported that, when pesticides are applied immediately before harvest, the level of pesticide residues on produce was greatly increased.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable information on the pesticides used, exposures, and perceptions on pesticide use, trends, and health symptoms by small-scale market gardeners’ farmers. It can be used also to develop a tool to contribute to the reformation of pesticide policy in Bughore-Kabare area in eastern of DR. Congo. The training of all the stakeholders, from the whole saler to the retailers and farmers, appears to be one of the most effective methods to promote IPM. Emerging markets for organic and sustainably managed horticultural products should help to boost investment in IPM options and especially biological control. The Congolese government must create a quarantine, control and surveillance service for phytosanitary products, fruits and vegetables within the DRC country and at these borders.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thank-full to Marc De Meyer of Invertebrates Section at the Royal Museum for Central Africa for the many tips, for the ideas, proofreading and correction of this article as well as for the unfailing emotional support. Additionally, thankful to the participants especially farmers and pesticide retailers at Bugorhe area of the Kabare territory South Kivu province for sharing their time with us. We would also like express our gratitude to labs of Entomology Section at the Researcher Centre in Natural Sciences for providing research laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest. The authors are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Rubabura KJA, Munyuli BMT, Bisimwa BE Kazi KS (2015) Invasive Fruit Fly, Ceratitis Species (Diptera: Tephritidae), Pests in South Kivu Region, Eastern of Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Innovation and Scientific Research 16(2): 403–408.

- Rubabura KJA, Chihire BP, Bisimwa BE (2019) Diversity and Abundance of Fruit Flies (Family: Tephritidae) in the Albertine Rift Zone, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Preliminary Prospects for Biological Control. Adv Plants Agric Res 9(1): 41‒48.

- Grasswitz TR, Fimbres OE (2013) Efficacy of a Physical Method for Control of Direct Pests of Apples and Peaches. J Appl Entomol 137: 790–800.

- Sharma RR, Pal RK, Sagar VR, Parmanick KK, Paul V, et al. (2014) Impact of Pre-Harvest Fruit-Bagging with Di_Erentcoloured Bags on Peel Colour and the Incidence of Insect Pests, Disease and Storage Disorders in ‘Royal Delicious’ Apple. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol 89(6): 613–618.

- Leite GLD, Fialho A, Zanuncio JC, Reis R, Da Costa CA (2014) Bagging Tomato Fruits: a Viable and Economical Method of Preventing Diseases and Insect Damage in Organic Production. Fla Entomol 97(1): 50–60.

- Filgueiras RMC, Pastori PL, Pereira FF, Coutinho CR, Kassab SO, et al. (2017) Agronomical Indicators and Incidence of Insect Borers of Tomato Fruits Protected with Non-Woven Fabric Bags. Ciência Rural 47(6): 1–6.

- Frank DL (2018) Evaluation of Fruit Bagging as a Pest Management Option for Direct Pests of Apple. Insects 9(4): 178.

- Grasswitz RT (2019) Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for Small-Scale Farms in Developed Economies: Challenges and Opportunities. Insects 10(6): 179.

- Ekesi S, Billah MK, Nderitu PW, Lux SA, Rwomushana I (2009) Evidence for Competitive Displacement of Ceratitiscosyra by the Invasive Fruit Fly Bactrocerainvadens (Diptera: Tephritidae) on Mango and Mechanisms Contributing to the Displacement. J Econ Entomol 02(3): 981–991.

- Ekesi S, Meyer MD, Mohamed SA, Virgilio M, Borgemeister C (2016) Taxonomy, Ecology, and Management of Native and Exotic Fruit Fly Species in Africa. Annu Rev Entomol 61: 219-238.

- Abang AF, Kouame CM, Abang M, Hanna R, Fotso AK (2014) Assessing Vegetable Farmer Knowledge of Diseases and Insect Pests of Vegetable and Management Practices under Tropical Conditions. International Journal of Vegetable Science 20(3): 240–253.

- Biasazin DT, Wondimu WT, Herrera LS, Larsson M, Mafra NA, et al. (2021) Dispersal and Competitive Release Affect the Management of Native and Invasive Tephritid Fruit Flies in Large and Smallholder Farms in Ethiopia. Scientific Report Springer Nature 11 2690: 1-14.

- Mengistie TB, Mol PJA, Oosterveer P (2017) Pesticide Use Practices Among Smallholder Vegetable Farmers in Ethiopian Central Rift Valley. Environ Dev Sustain 19: 301–324.

- Anderson AJ, Ellsworth CP, Faria CJ, Head PG, Owen DKM, et al. (2019) Genetically Engineered Crops: Importance of Diversified Integrated Pest Management for Agricultural Sustainability. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 7: 24.

- Panuwet P, Siriwong W, Prapamontol T, Ryan PB, Fiedler N, et al. (2012) Agricultural Pesticide Management in Thailand: Status and Population Health Risk. Environ Sci Policy 17: 72–81.

- Ahouangninou C, Martin T, Edorh P, Bio BS, Samuel O, et al. (2012) Characterization of Health and Environmental Risks of Pesticide Use in Market-Gardening in the Rural City of Tori-Bossito in Benin, West Africa. Journal of Environmental Protection 3(3): 241–248.

- Damte T, Tabor G (2015) Small Scale Vegetable Producers’ Perception of Pests and Pesticide Uses in East Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Pest Management 61(3): 1–8.

- Vontas J, Hernández CP, Margaritopoulos TJ, Ortego FH, et al. (2011) Insecticide resistance in Tephritid flies. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 100(3): 199-205.

- Koirala P, Dhakal S, Tamrakar A (2009) Pesticide application and Food Safety Issue in Nepal. The Journal of Agriculture and Environment 10: 128-132.

- Mondedji AD, Nyamador WS, Amevoin K, Adéoti R, Abbévi GA, et al. (2015) Analyse de quelques aspects du système de production légumière et perception des producteurs de l’utilisation d’extraits botaniques dans la gestion des insectes ravageurs des cultures maraîchères au Sud du Togo. International Journal of Biology and Chemistry Sciences 9(1): 98-107.

- Muliele MT, Manzenza MC, Ekuke WL, Diaka PC, Ndikubwayo MD, et al. (2017) Utilisation Et Gestion Des Pesticides En Cultures Maraîchères: Cas De La Zone De Nkolo Dans La Province Du Kongo Central, République Démocratique Du Congo. Journal of Applied Biosciences 119: 11954-11972.

- Mawussi G, Kolani L, Devault DA, Koffi KAA, Sanda K (2015) Utilisation De Pesticides Chimiques Dans Les Systèmes De Production Maraîchers En Afrique De l’Ouest Et Conséquences Sur Les Sols Et La Ressource En Eau : Le Cas Du Togo. 44è congrès du Groupe Français des Pesticides, 26-29 mai 2014, Actes du colloque, Schoelcher 46-53.

- Mühlenberg M, Slowik J, Steinhauer B (1995) Parc National de Kahuzi-Biega. Projet de Coopération Germano-Zaïroise, IZCN/GTZ pp. 52.

- Scheaffer RL, Mendenhall W, Ott L, Kenneth Gerow (1987) Elementary Survey Sampling. Journal of American Statistical Association 400: 1185-1186.

- Deroo M, Dussaix AM (1980) Pratique Et Analyse Des Enquêtes Par Sondage. PUF 1980.

- Dagnelie P (2008) Principes d'expérimentation: planification des expériences et analyse de leurs ré Gembloux, Presses agronomiques, et édition électronique, pp. 397.

- Gbénonchi M, Lankondjoa K, Damien AD, Koffi KAA, Komla S, et al. (2014) Utilisation De Pesticides Chimiques Dans Les Systèmes De Production Maraîchers En Afrique De l’Ouest Et Conséquences Sur Les Sols Et La Ressource En Eau : Le Cas Du Togo. 44è congrès du Groupe Français des Pesticides, pp. 46-53.

- Mondedji AD, Nyamador WS, Amevoin K, Adéoti R, Abbévi GA, et al. (2015) Analyse de quelques aspects du système de production légumière et perception des producteurs de l’utilisation d’extraits botaniques dans la gestion des insectes ravageurs des cultures maraîchères au Sud du Togo. International Journal of Biology and Chemistry Sciences 9(1): 98-107.

- Wade CS (2003) L’utilisation Des Pesticides Dans L’agriculture Péri-Urbaine Et Son Impact Sur L’environnement. Etude Menée Dans La Région De Thiè

- Dinham B (2003) Growing Vegetables in Developing Countries for Local Urban Populations and Export Markets: Problems Confronting Small-Scale Producers. Pest Manag Sci 59(5): 575-582.

- Ngowi AVF, Mbise TJ, Ijani ASM, London L, Ajayi OC (2007) Pesticides Use by Smallholder Farmers in Vegetable Production in Northern Tanzania. Crop Prot 26(11): 1617-1624.

- Beránková M, Hojerová J, Melegová (2017) Exposure of Amateur Gardeners to Pesticides Via Non-Gloved Skin Per Day. Food and Chemical toxicology 108(A): 224-235.

- Sougnabe SP, Yandia A, Acheleke J, Brevault T, Vaissayre M, et al. (2009) Pratiques Phytosanitaires Paysannes Dans Les Savanes d'Afrique Centrale.

- Kanda M, Boundjou GD, Wala K, Gnandi K, Batawila K (2013) Application Des Pesticides En Agriculture Maraîchère Au Togo. Vertig O La revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement 13(1).

- Tachin ES (2011) Protection Des Végétaux Et Gestion Des Cultures Maraîchères : Les Pesticides Chimiques, A La Fois Utiles Et Dangereux. La Nouvelle Tribune.

- Novikova II, Litvinenko AI, Boikova IV, Yaroshenko VA, Kalko GV (2003) Biological Activity of New Microbiological Preparations Alirins B and S Designed for Plant Protection against Diseases. Biological Activity of Alirins against Diseases of Vegetable Crops and Potato. Mikologiya i Fitopatologiya 37(1): 92–98.

- Santo MEG, Marrama L, Ndiaye K, Coly M, Faye O (2002) Investigation of Deaths in an Area of Groundnut Plantations in Casamance, South of Senegal after Exposure to Carbofuran, Thiram and Benomyl. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 381–388.

- Gupta RCJ (1994) Carbofuran Toxicity. Toxical Environ Health 43(4): 383–418.

- WHO/UNEP (1990) Public Health Impact of Pesticides used in Agriculture. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Legutowska H, Kucharczyk H, Surowiec J (2002) Control of Thrips Infestation on Leek by Intercropping with Clover, Carrot or Bean. International Society Horticultural Science 579: 571-574.

- Hummel RL, Walgenbach JF, Hoyt GD, Kennedy GG (2002) Effects of Production System on Vegetable Arthropods and their Natural Enemies. Agric Ecosyst Environ 93(1–3): 165–176.

- Sibanda T, Dobson HM, Cooper JF, Manyangarirwa W, Chiimba W (2000) Pest Management Challenges for Smallholder Vegetable Farmers in Zimbabwe. Crop Prot 19(8-10): 807–815.

- Assogba KF, Anihouvi P, Achigan E, Sikirou R, Boko A, et al. (2017) Pratiques Culturales Et Teneurs En Eléments Anti Nutritionnels (Nitrates Et Pesticides) Du Solanummacrocarpum Au Sud Du Bé African Journal of Food agriculture nutrition and development 7(4): 1-21.

- Ghorbel A, LazregAref H, Darouiche MH, Nouri NM, Masmoudi ML, et al. (2016) Estimation Du Niveau De Connaissance Et Analyse Toxicologique Chez Des Manipulateurs De Pesticides Organophosphorés Exposés Au Fénitrothion Dans La Région De Sfax, En Tunisie. International Journal of Innovation and Scientific Research 25(1): 199-211.

- Lwin TZ, Min AZ, Robson MG, Siriwong W (2017) Awareness of Safety Measures on Pesticide Use among Farm Workers in Selected Villages of Aunglan Township, Magway Division, Myanmar. Journal of Health Research 31(5): 403-409.

- Smit ZK, Indjic D, Belic S, Miloradov M (2002) Effect of Water Quality on Physical Properties and Biological Activity of Tank Mix Insecticide-Fungicide Spray. International Society Horticultural Science 579: 551-556.

- Antonella F, Bent I, Manuela T, Sara V, Macro M (2001) Preventing Health Risk from the Use of Pesticides in Agriculture. Protecting workers health series.

- Epstein L, Bassein S (2003) Patterns of Pesticide Use in California and the Implications for Strategies for Reduction of Pesticides. Annu Rev Phytopathol 41: 351-375.

- Abate T, Huis VA, Ampofo JKO (2000) Pest Management Strategies in Traditional Agriculture : An African Perspective. Annu Rev Entomol 45: 631-659.

- Onil S, Louis SL (2001) Guide De Prévention Pour Les Utilisateurs Des Pesticides En Cultures Maraîchè IRSST pp. 92.

- Kishi M, Hirschon N, Djajadisastra M, Satterlee LN, Strowman S, et al. (1995) Relationship of Pesticide Spraying to Signs and Symptoms in Indonesian Farmers. Scand J Work Environ Health 21(2): 124-133.

- Ajayi OC (2000) Pesticide Use Practices, Productivity and Farmer’s Health: The Case of Cotton-Rice Systems in Cote d’Ivoire, West Africa. Hannover pp. 172.

- Diary K (2019) Banned Pesticides in Nepal. In MO Development Agriculture Information Training Center.

- Congo AK (2013) Risques Sanitaires Associés A L’utilisation De Pesticides Autour De Petites Retenues: Cas Du Barrage De Loumbila. Thèse de Master pp. 57.

- Ahouangninou C (2013) Durabilité De La Production Maraîchère Au Sud-Bénin : Un Essai De L’approche Ecosysté Thèse de doctorat pp. 349.

- Kanda M, Boundjou GD, Wala K, Gnandi K, Batawila K, et al. (2013) Application Des Pesticides En Agriculture Maraîchère Au Togo. VertigO La revue électronique en sciences de l'environnement 13(1).

- WHO (2012) Health and Environment Linkage Initiative, Toxic hazards, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Jeyanthi H, Kombairaju S (2005) Pesticide Use in Vegetable Crops: Frequency, Intensity and Determinant Factors. Agricultural Economics Research Review 18(2): 209–221.

© 2022 Jean ARK. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)