- Submissions

Full Text

Approaches in Poultry, Dairy & Veterinary Sciences

Pre-cooling of Human Top Athletes and Sport Horses Under Heat Stress: An Opportunity or Wishful Thinking? A Review

Jos Noordhuizen*

School of Agriculture & Veterinary Science, Australia

*Corresponding author: Jos Noordhuizen, School of Agriculture & Veterinary Science, Wagga, NSW, Australia

Submission: November 02, 2021;Published: November 29, 2021

ISSN: 2576-9162 Volume8 Issue4

Abstract

In this review paper attention is given to cooling methods applied in human top athletes and in sport horses under conditions of heat stress. Three cooling principles are addressed: pre-competition cooling, per-competition cooling and post-competition cooling. Each of these are elaborated with respect to practicality and to their advantages and disadvantages. Post-cooling is generally accepted in both species but should be executed in the best possible way. Pre-cooling has been subject of study in human top athletes. Effects have been determined but not each method is applicable or effective and even not in each discipline. The preferred method is cool-cold water immersion of endurance athletes. In sport horses, post-competition cooling is common use. However, several methods often applied in the field are not the most effective because they are too much time-consuming, labor-intensive, and inefficient. Pre-cooling in sport horses is hardly or not applied; scientifically justified studies are lacking. Nevertheless, precooling is sometimes proposed to improve welfare, health, and performance of these horses. The main conclusions are that human top athletes and sport horses are physiologically not comparable under heat stress conditions and cooling, that pre-cooling of horses should not be proposed as long as appropriate studies are not conducted, and finally that in sport horses the most appropriate post-cooling should be applied: rapidly after the finish; let-down of masses cool-cold water and at the same time low air-speed fanning in repeated cooling cycles, while checking clinical parameters to determine whether cooling can be stopped.

Introduction

Heat stress occurs when a horse or a human being is no longer able to get rid of the heat

accumulated in the body during a performance or intensive training and is due to high ambient

temperatures (above 25 °C) most often accompanied by high air humidity levels (above 60%).

Heat stress conditions impact, often severely, the performance, health, and welfare of sport

horses as well as of human top athletes. In sport horses, different methods of cooling are

being applied, which do not all result in the best possible cooling effects. Poor methods are,

for example, using buckets with cool water to throw on the horse, or using a water garden

hose for a short time after performance.

In humans, heat stress problems are well-known and have been subject of research over

the past decennia, especially in workers under heat stress conditions such as forgery workers

and underground miners, as well as the military; it is considered an occupational hazard

(Singh et al., 2009). Heat stress is associated with poor performance and decreased comfort

(Thatcher et al., 2005). In mine workers and forgers, heat stress impact could somewhat be

reduced by inserting resting periods at regular time intervals in the working schedule Mustafa

et al. [1]. Appropriate cooling of heat stressed human top athletes, such as sprinters and longdistance

runners under heat stress conditions, is also a subject of research for several years.

One distinguishes in cooling procedures: PRE-competition cooling, PER-competition cooling,

and POST-competition cooling Bongers et al. [2].

Positive effects of these three methods are quite variable in

human athletes Bongers et al. [2], in such a way that researchers

have also studied the effects of mixed cooling methods. Question is

whether any positive outcomes of these cooling methods, especially

pre-cooling could also be applicable to sport horses. This paper

addresses the three named cooling methods in cooling human

athletes and their effects, and to subsequently ‘translate’ the best

outcomes to assess their applicability in sport horses, both under

heat stress conditions.

Heat Stress & Cooling Methods in Human Athletes

Human core body temperature serves to maintain all biological

body functions. When core body temperature increases, for

example, above 40 °C under heat stress conditions, fatigue installs,

and various illnesses may occur. The severity of ambient heat stress

is best assessed using a WBGT-index (wet bulb globe test) which is

highlighted in the heat stress standard ISO 7243 for monitoring and

assessing hot environments Parson [3]. When changes of at least

2 °C occur in core body temperature, problems can already occur

in humans under heat stress conditions. Associated dehydration

affects physical, mental, and psychomotor functions Mustafa et al.

[1].

Sometimes indices such as Body Mass Index (BMI) and Body

Fat Percentage Index (BFPI) are used for assessing the metabolic

condition of people in relation to heat stress effects. In general, a

higher BMI is associated with a higher risk of heat stress effects. In

these indices, body weight and body height, or body fat percentage

are calculated according to a formula. However, for athletes the BMI

is not indicated as parameter because muscular mass and bone

mass are not considered McArdle et al. [4]. The BFPI is also being

used for athletes, with normal values of 20.1 to 25.0 (man) and 18.7

to 23.8 (females) (www.brianmac.co.uk). It would be great to have

a simple but reliable test to assess metabolic status in human top

athletes.

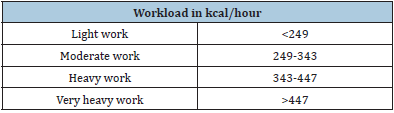

Table 1: The typology of human workload presented in kcal per hour.

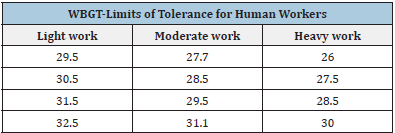

Table 2: Limits of WBGT-readings for tolerance in human workers.

In Table 1 the typology of workload is presented in kcal/hour

Singh et al. In Table 2 are presented the accepted tolerance limits

of WBGT-readings for humans (ACGIH, 2001). For top athletes the

authors refer to the classes ‘’heavy work’’ and ‘’very heavy work’’,

especially when performing under hot humid conditions.

Skin temperature increases when intensive exercise is

effectuated over long duration. When both core body temperature

and skin temperature increase, top athletes’ performance

decreases because the heat transfer gradient core body-skin is

lowered. Therefore, cooling is primarily focused on this core body

temperature.

The following Table 3 presents some examples of PRE-cooling

options studied Bongers et al. [2].

Table 3: Overview of some PRE-cooling options in human athletes with related features of applicability. PRE-cooling means pre-competition cooling.

The methods presented in Table 3 are commonly applied as a

PRE-cooling strategy. This strategy is basically meant to increase

the heat storage capacity in the body contrarily to POST-cooling.

POST-cooling is meant to attenuate heat storage capacity after

performance or exercise. According to studies, the average PREcooling

effect obtained with methods named in Table 3 was 5.7%. A

mixed cooling method yielded an effective performance increase of

7.3%. Cold water immersion had an effect of 6.5%. Unfortunately,

there are no studies conducted in which a comparison between the

three cooling strategies is presented. Moreover, standardization of

measurements, such as in the assessment of increased performance

due to cooling method, is still an issue of debate which makes the

comparison of study results nearly impossible. An alternative is

the parameter ‘’standardized effect size (SES or Cohen’s D value)’’.

Bongers et al. [2] explain the advantages of this parameter for

comparison of methods. For mixed cooling methods this parameter

would be 0.72. For cold water immersion this value is 0.49, while

for cold water and ice slurry ingestion this value is 0.40 Bongers

et al. [2].

However, there is a difference between the cooling effects in

sprint athletes and those in endurance athletes. PRE-cooling is not beneficial for sprinters’ performance. The so cooled muscles have

a lower power output and a decreased anaerobic metabolism. The

final PRE-cooling effects depend on the ambient temperature, the

exercise set-up, and the applied cooling strategy. Moreover, the

PRE-cooling effects diminishes after 20 to 25 min.

PER-cooling (= cooling during exercise/performance) might

extend the PRE-cooling benefits in endurance athletes and, hence,

may have a larger potential benefit on thermoregulation and

performance. The PER-cooling effects of using ice-vests (Table 1)

are greater than those of cold-water ingestion, which on its turn

has a greater effect than those of cooling packs. Cold water and

ice slurry ingestion yielded a performance increase of 5.7% (SES=

0.88), while for ice or cooling vests this value was 11% (SES= 0.67),

for facial wind and water spraying it was 18.7% (SES= 0.54). The

overall mean effect of PER-cooling was 9.3%.

Most clinical studies on PER-cooling did not result in any

positive effect of PER-cooling, other than an increased interval until

exhaustion, varying between 3% and 21% longer. Moreover, PERcooling

showed more positive results on performance at ambient

temperatures below 30 °C and not at hot temperatures (above 30

°C). Finally, the combination of PRE- and POST cooling methods

showed highly variable outcomes.

POST-cooling is meant to reduce core body temperature, skin

temperature and rectal temperature, hence, to attenuate heat

storage capacity after exercise/performance. Cold water immersion

(5 to 15 °C) is the most effective method Marino [5]. Other methods

like cold air exposure (-30 °C, which is very aggressive) and

cryotherapy (at -100 °C, then reducing inflammatory processes in

the body, but very expensive) are not very practical.

The effect of heat stress on the body is the production of

reactive oxygen species (ROS), also named oxygen radicals. These

ROS result in denaturation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.

This causes a change in muscle contraction patterns rendering the

muscles prone to edema and loss of performance of the muscles.

The latter leads to a secondary immune response in answer to the

intensive exercise or performance (e.g. endurance athletes!). POSTcooling

contributes to a decrease of inflammatory responses of

the body and hence lowers the muscle pain but also decreases the

generation of muscle force. POST-cooling induces vasoconstriction

in muscle tissue and a decrease in muscle temperature, both lead to

a reduction in lymphatic and capillary permeability and, hence, to

less muscle edema.

Conclusion for Top Athletes

PRE-cooling using mixed methods may have some effect under heat stress conditions in endurance athletes, but hardly or not in sprinters. The duration of a beneficial effect is, however, rather short. PER-cooling is not an approach of choice to increase heatresistant performance. Clinical studies often showed variable or no positive results. Positive results have been obtained at ambient temperatures under 30 °C mainly. POST-cooling using cold water immersion looks as the best way to cool the overheated body, limiting muscle edema and pain as well as immune responses to the exercise/performance.

Heat Stress & Cooling Methods in Sport Horses

Sport horses have a thermoneutral zone between about

5 °C and 20 °C. This means that they can get rid of accumulated

body heat rather easily in this zone. The so-called Upper Critical

Temperature (UCT) is somewhere between 20 °C and 30 °C. This

variation depends on breed, training level, feeding status, metabolic

status, and age. Body heat is generated by body maintenance

processes, feed and metabolism, and exercise/performance. Above

the UCT the horse must activate physiological body systems to get

rid of the body heat. It is generally accepted that heat stress starts

at about 22 °C Noordhuizen [6]. With regard to Table 1 & Table 2 it

can be concluded that for sport horses the reference values under

heat stress conditions are the same as for human top athletes, as

they are for riders and horse grooms. Note that horses lose about

15L body fluids per hour in dry hot conditions; in hot humid

conditions this loss can increase up to 30L per hour. Most of the

heat is normally eliminated by sweating and evaporation from the

skin surface (75%), respiration (22%) and convection (3%). In heat

stress conditions these percentages drop drastically to 30%--10%-

-1% respectively.

Thoroughbred racehorses have a particular position because

they are not comparable to other breeds. These racehorses perform

over relatively short distances in an explosive manner. Muscle heat

increases exponentially due to a high metabolic level coupled to the

explosive performance. Body heat level rises dramatically in such

a way that skin temperatures may go up to 50 °C. In some cases

(about 1%, MacDonald et al., central nervous system failures and

brain ischemia occur (Brownlow et al., 2016; Brownlow, 2019;

Takahashi et al. [7]. This phenomenon is named ‘’exertion heat

illness’’ (Australia) and is also known in humans. In South Africa it

is named ‘’Postrace distress syndrome’’.

Horses heat up 3 to 10 times faster than humans. The

metabolism of sport horses is not comparable to that in human

athletes. The skin surface of horses is relatively smaller than that of

humans due to different body biomass and body weight. Sweating

and evaporation from the skin are therefore paramount for a horse

Hodgson et al. [8], more than for a human. The loss of body fluids

leads to a less efficient blood circulation and the blood volume

becomes smaller. On its turn, this decreased blood volume causes a

less blood flow to the skin, to the muscles and to the intestines. The

combined results are less sweating, lower energy flow to muscles

and loss of performance, less absorption of water and electrolytes

in the intestines, and higher risk of colic; horses’ intestines are

sensitive Noordhuizen [6].

As in the preceding paragraph on human athletes, heat stress

indices are also used in the sport horse sector. The Temperature-

Humidity -Index (THI) is one example, but only to get an overall idea

about heat stress severeness, because THI lacks several relevant

parameters such as wind speed, shadow, and direct sun radiation.

As indicated above, a better parameter is the Wet Bulb Globe Test (WBGT) which includes such parameters and is more reliable than

THI. One of the factors responsible for the variation in interpretation

of WBGT-results is the metabolic status of horse (and/or rider). The

higher that status, the lower the critical threshold value for WBGT

must be set. That status is, however, generally unknown, and hence

a source of variation in read outs. It would be highly indicated to

have a simple but reliable test to assess the metabolic status of

sport horses for assessing health risks.

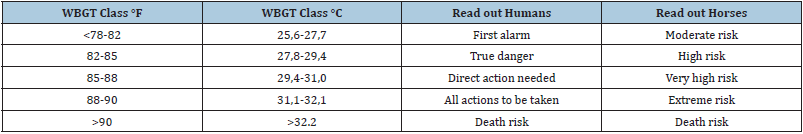

WBGT-readings for sport horses and humans are presented in

Table 4 with their risk level Noordhuizen [6]. Note that WBGT read

outs in °C or °F are not the same as ambient temperature readings.

The risk areas are comparable between humans and horses but

note that the data in Table 4 are not specifically related to top

athletes nor to high level sport horses; they have a more general

relevance. This means that individual top athletes and sport horses

could be far more at risk than the general population. Cooling of

a heat stressed sport horse is currently done in several ways but

commonly as POST-cooling Williamson et al. [9]; Kohn et al. [10],

for example: cool water hosing using a garden hose for a certain

time-period, throwing buckets of cool water on the skin, using

misters (fans with tiny droplet spray) installed in front of the horse.

These methods lack effectivity: Most often no fans are being used

to enhance evaporation, the methods are time-consuming and are

labor-intensive. The latest development are equine cooling units,

ECU (single, as cooling alleys or as cooling carrousels; in the latter

up to 12 horses can be cooled simultaneously, Noordhuizen [6]. For

a single stand (ECU) cooling takes place activating at the same time

both a special sprinkler for a mass cold water let down and two fans

at low speed to enhance evaporation from the skin (see Photo). This

procedure is done for 5-10 min and can be repeated until clinical

parameter values are back to normal. These clinical parameters are

heart rate, respiration rate, rectal temperature, dehydration test

results (skinfold test; capillary refill test).

Table 4: WBGT readings (°F and °C) and interpretation for humans and for sport horses.

Sources: USGS Survey Manual ‘’Management of Occupational Heat Stress’’, chapter 45; Manual of Naval Preventive Medicine ‘’Prevention of Heat and Cold Stress’’, chapter 3; OSHA Technical Manual section III ‘’Heat Stress’’, chapter 4; National Weather Service, Tulsa Forecast Office, WBGT; Noordhuizen [6].

PRE-cooling and its effects on performance, health issues

and welfare has never been fully studied in horses. Results of

studies on PRE-, PER- and POST-cooling respectively or in possible

combinations are not known to the author’s knowledge. The use of

cold water or ice slurry ingestion in horses is counterproductive

because of the sensitivity of the intestines of the horse leading

to health problems. Recently, a paper was published proposing

PRE-cooling for horses, possibly in addition to POST-cooling

Klous et al. [11]. These authors found a slight improvement in

rectal temperature (0.3 °C) and shoulder/rump skin temperature

(2 to 3 °C) in ten elite eventing horses under ambient conditions

which were being far from heat stress conditions: WBGT-readings

18.5±3.8 °C, while the level and duration of exercise was only

moderate. Heart rate, plasma lactate concentration, sweat rate

and sweat concentration of electrolytes were not affected by PREcooling

in this study.

The conclusion of the authors that PRE-cooling could

potentially improve welfare during competition seems rather

premature. A potential positive effect of PRE-cooling diminishes

rapidly in endurance athletes: in 20-25 min. Therefore, an effect

seems to be of too short duration, especially in eventing horses and

in endurance horses which run up to 160km.

The Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) in Lausanne,

Switzerland, advises to start PRE-cooling of horses when WBGTread

out is above 28 °C, especially in eventing horses for the

disciplines of cross-country and jumping Marlin et al. [12]. However,

there is so far no scientific basis for this kind of advice at all.

Conclusions for Sport Horses

PRE-cooling of sport horses before competition starts could

be an idea, but if there is no substantial, scientifically justified

evidence of positive effects for performance, health and welfare, in

eventing and endurance horses in particular, one should be careful

to propose such an approach, not in the least because an effect, if

any, seems to be of short duration. For endurance horses a PREcooling

seems even inappropriate.

PER-cooling is hardly or not feasible during competition given

the short time available for such a cooling and the fact that there

is a saddle on the horse limiting the surface for cooling. The use

of misters during competition is not advised for cooling horses,

because very small droplets are produced which diminishes the

cooling effect if any. Misters are often used to cool down the air in

the stable, hence improving respiration.

POST-cooling still is the best way to help a horse to get rid

of accumulated body heat after a competition, but it must be

conditioned. These conditions are that cooling should be executed

right after the finish, that cooling should be done using mass coolcold

water let-down at the same time as low-speed fanning, and that

clinical check-ups should be done to determine whether the cooling (duration) has been effective. It is peculiar that adequate fanning

is hardly considered in studies dealing with heat evaporation. For

horses like in humans it enhances evaporation and stimulates

cooling effects more. Large studies among underground miners in

the USA and Turkey pinpoint these effects of fanning (Mustafa et al.

[1]; Parsons [3] and Roghanchi et al. [13].

An once heat stressed horse will show less performance, health

and welfare, and it will be worse during following exposures.

Therefore, the three conditions are paramount. Noordhuizen [6]

provides the options to meet the demands of the three conditions

(equine cooling unit; equine cooling alley; equine cooling carousel).

These products can, moreover, be equipped with Bluetooth

operated electrocardiogram devices to monitor heart function and

heart failures.

It is not uncommon that a cooled horse becomes a recidivist one

or two hours later and must be cooled again. Surveillance of cooled

horses the first 2 hours after cooling is a therefore a necessity.

Brownlow (in Noordhuizen [6] provides scoring cards for assessing

severity of heat stress in Thoroughbred racehorses and triggers to

start the necessary additional medical treatment of horses in which

the central nervous system is affected. Next to the sport horses, one

should pay attention to the riders and the grooms possibly affected

by heat stress too. It that respect riders are comparable to top

athletes. Noordhuizen [6] provides several suggestions to deal with

the problem, while for competition officials the author refers to the

preceding paragraphs on top athletes.

Discussion and Final Remarks

In the equine world it seems to be common to address heat

stress issues from a human point of view: ‘’if the rider thinks it is

not too hot, the exercising horse will feel the same’’. This is probably

the main reason that many applied cooling methods in horses are

not efficient. They take too much time, are laborious and do not

meet the primary demands such as applying masses of cool-cold

water and low air-speed fanning at the same time.

Humans and horses have a different thermoneutral zone and

a different metabolic state. Horses heat up 3 to 10 times faster

than humans. Human metabolism is not at the same level as that in

horses and an even greater discrepancy occurs between top athletes

and high-level sport horses. Horses need to get rid of heat by sweat

and evaporation through the skin mainly. Panting may contribute

somewhat to heat loss but only when the ambient temperature is 5

°C lower than core body temperature. Humans sweat primarily by

their head. The sweat in horses is four times more concentrated in

electrolytes than that in humans. Electrolytes are hence essential

in the horse.

Horses produce heat from body function maintenance

processes, metabolic processes related to feed ingestion, and

performance/exercise. More than 50% of the energy available in

muscles is converted into heat. NASA has determined some 30 years

ago that human performance under heat stress conditions of 32 °C

was 30% less than under normal temperatures while precision of

work was 300% less (Figure 1). At temperatures of 37 °C these

percentages were 50% and 700% respectively Greenleaf et al. [14].

Figure 1: An example of a single Equine Cooling Unit (ECU) in operation.

Note: The wide spread of the sprinkler covering the whole body and the position of the two fans at the back of the ECU (courtesy of Noordhuizen [6].

In conclusion, as shown in the preceding paragraphs, the effects of PRE-, PER-, POST-cooling are not the same in humans and horses [15]. Moreover, scientifically justified studies on this subject are lacking in (sport)horses. Therefore, it still looks too premature to propose PRE-cooling of sport horses in competition under conditions of heat stress.

References

- Mustafa O, Saim S, Syhan O (2005) A study of heat stress parameters at Kozlu Coalmine. Turkey J of Occupational Health 47(4): 343-345.

- Bongers CCWG, Hopman MTE, Eijsvogels TMH (2017) Cooling interventions for athletes: An overview of effectiveness, physiological mechanisms and practical considerations. Temperature 4(1): 60-78.

- Parsons KC (2006) Heat stress Standard ISO 7243 and its global application: Review article. Industrial Health 44(3): 368-379.

- McArdle WD, Katch F, Katch VL (2000) Essentials of exercise physiology. (2nd edn), Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA.

- Marino FE (2002) Methods, advantages, and limitations of body cooling for exercise performance. Br J Sports Med 36(2): 89-94.

- Noordhuizen JPTM (2020) Heat stress in sport horses. Context Products Ltd., Packington, UK, pp. 1-49.

- Takahashi Y, Ohmura H, Mukai K, Shiose T, Takahashi T (2020) A comparison of 5 cooling methods in hot and humid environments in Thoroughbred horses. J Equine Vet Sci 91: 103130.

- Hodgson D, Davis RE, McConaghy FF (1994) Thermoregulation in the horse in response to exercise. Br Vet J 150(3): 219-235.

- Williamson L, White S, Maykut P, Andrew F, Sommerdah, C, Green E (1995) Comparison between two post exercise cooling methods. Equine Vet J 27(S18): 337-340.

- Kohn CW, Hinchcliff KW, McKeever KH (1999) Evaluation of washing with cold water to facilitate heat dissipation in horses exercised in hot, humid conditions. Am J Vet Res 60(3): 299-305.

- Klous L, Siegers E, vanden Broek J, Folkerts M, Gerret N, et al. (2020) Effects of pre-cooling on thermophysiological responses in elite eventing horses. Animals 10(9): 1664.

- Marlin DJ, Misheff M, Whitehead P (2018) Optimising performance in a challenging climate. In Proceedings of the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) Sports Forum 2018, Lausanne, Switzerland, 26-27, pp. 11-24.

- Roghanchi P, Sunkpal M, Carpenter K (2015) Application of heat stress indices in underground mines. Dept Of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering, University of Nevada, Reno, USA, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOS), Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration (SME) Northern Nevada Section.

- Greenleaf JE, Kacinka-Uscilko H (1989) Acclimitization to heat in humans. NASA Report T 10101, pp. 1-41.

- https://www.brianmac.co.uk/

© 2021 Jos Noordhuizen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)