- Submissions

Full Text

Aspects in Mining & Mineral Science

Environmental Impacts of Mining Activities in Ngororero Mining Company (NMC): Ngororero District-Rwanda

Nsengiyumva Cedrick*, Ndagijimana Soleil Marie Aimee and Digne Edmond Rwabuhungu

Geo-Information Science for Environment and Sustainable Development, BSc (Hons) in Applied Geology, Rwanda

*Corresponding author:Nsengiyumva Cedrick, Geo-Information Science for Environment and Sustainable Development, BSc (Hons) in Applied Geology, Rwanda

Submission: January 27, 2023; Published: March 23, 2023

ISSN 2578-0255Volume11 Issue2

Abstract

The contribution of the mining sector to Rwanda’s economic growth and development is very significant as the mining sector is the second to contribute to government GDP after tourism. The mining industry in Rwanda consists of both small-scale and medium-scale mining, each of which affects the environment however the country is working toward transforming it into large-scale mining. This paper summarizes some of the key environmental impacts associated with different stages of mine life in Ngororero Mining Company, one of the companies which provide high production of cassiterite and coltan. The primary data, as well as the secondary data, were collected including a review of the existing relevant pieces of literature, field visits and observation, interviews with mining operators, and workers in different aspects focusing on environmentalists. The findings showed that mining activities affect the environment in all its stages. However, the environment is highly affected in the absence of proper tailing management. The paper concluded by recommending the mining owners design the proper tailings management facilities.

Keywords:Environmental impact; Mining; Ngororero mining company; Tailings

Abbreviations:FDI: Foreign Direct Investments; EIA: Environmental Impact Assessment; NMC: Ngororero Mining Company; OHS: Occupational Health and Safety

Introduction

Mining is one of the highly practised activities in Rwanda and the biggest source of export revenues after tourism [1]. There is a long, almost 100-year mining history for tin, tungsten, and tantalum (3T) ores in Rwanda, presently mainly manifested as artisanal and small-scale mining. Mining in Rwanda nowadays forms one of the fastest-growing sectors and makes increasingly important contributions to off-farm employment in rural areas while also being one of the most significant Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) target sectors [2]. Though most operating companies are small-scale or artisanal, it is largely contributing to the economic growth of the country and increased the employment rate in Rwanda, where about 54,000 people are employed in the sector [3]. Being an old profession, mining is long known to be difficult and responsible for various injuries and diseases, mining without an impact on the environment and inhabitants of the mine’s surroundings is impossible. A long time ago, the economy derived from mining activities was of the first importance, while their impact on people and the environment was hardly noticed. Today many mining operations create an enriched landscape. Opencast pits hold beautiful new landscapes and hard rock mines and quarries grow into ecosystems that are rare islands of nature in a sea of human occupation” [4]. As a multidisciplinary industry, mining is conventionally classified as metalliferous or coal, and as surface or underground. Mining is done through a series of processes from exploration to mine decommissioning and rehabilitation, some mineral processing is often done at the mine site [5]. The mining activities are well-thought-out to be high-risk work and classified among supposed perilous/dangerous livelihoods. This is due to the fact that it includes tough corporal efforts under circumstances of risky uneasiness, ear-damaging noise, humidity, and a confined environment [6]. Despite that mining generates higher income, it also contributes to environmental degradation as well as environmental pollution by either mining activities through different mining stages or the techniques of waste disposal practised by a certain mine [7]. Through the designing process of mining activities, the natural environment is mostly disturbed and transformed. Such disturbance and transformation, in most instances, have a permanent and irreversible impact on ecosystem processes and how the ecosystem functions and the resulting stream of ecosystem goods and services flowing from the site being impacted. This change in the flow of ecosystem goods and services varies, and quite significantly so, before, during, and after mining [3].

According to Ahmad [8], dual work-related dangers both traditional and new are faced by workers in intricate work situations. This is due to the prompt industrial advance, technological breakthroughs, and growth to a worldwide scale in the few past years, due to all of these, diseases, accidents, hurts, infirmities, and fatalities may occur. Work-related health is very necessary since occupational health problems have effects on individuals and their families, communities as well as the residents of the world. Dealing with the well-being and good health of the employees, family members, employers, and other stakeholders, the OHS evaluates all features and aspects endangering the good health and conditions of workers and their working places respectively, thus forestalling, recognizing valuation, and control of dangers. Therefore, the standard of occupational health and safety at any working place should be the main basis of employees’ good health [8]. Waste management is among the principal issues in the Rwandan mining sector. Though mining activities boost the country’s economy and improve the living standards of the population, they are also associated with negative effects. Mining in Rwanda is mostly artisanal and thus very risky and affects the environment negatively. Improper waste disposal being the main challenge, REMA [9] has put up guidelines for the companies to follow to do sustainable mining by protecting the environment [9]. In Rwanda, there is a National Environment Policy of 2018, and LAW N°48/2018 of 13/08/2018 Environment are in place to ensure the protection of the ecosystems from degradation and pollution as well as guide rehabilitation of ecosystems being degraded. Articles 43, 44, and 45 require that all activities that are likely to cause significant environmental impacts carry out a feasible Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Law on Mining and Quarry Operations, Law No 58/2018 of 13/08/2018 ‘Before the commencement of any operations, mining license holders must submit to the competent authority a report on the study on Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and social welfare approved by ‘public organ’ that is relevant. The main objective of this study is to assess the common environmental impacts caused by mining activities using the existing pieces of literature and findings, by specifically looking at the environment surrounding Ngororero Mining Company site in Rwanda. The outcomes of this study will contribute to providing the basis for Ngororero Mining Company owners to make decisions on which mining activities can comply with the environment surrounding this mining concession.

Geological Setting of the Study Area

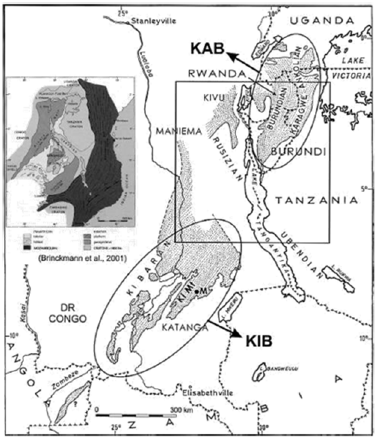

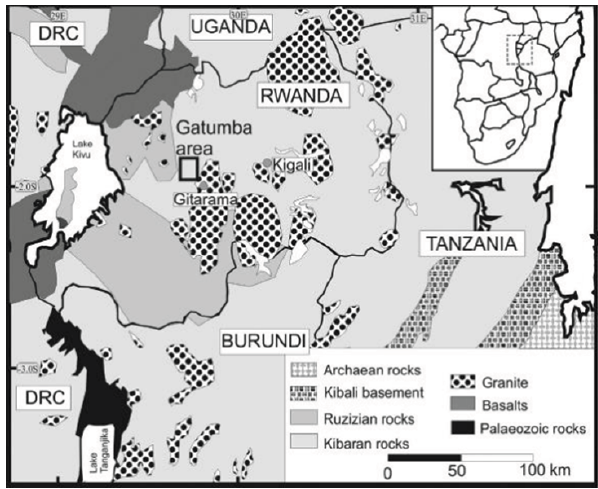

Rwandan geology is dominated by Mesoproterozoic (1.6-1.0 Ga) metasedimentary rocks that were intruded by two generations of granite [10]. Above this basement on the lithostratigraphy of Rwanda, there are Cenozoic volcanic rocks that are located in the Northwest and Southwest of Rwanda. The geology of Rwanda is a part of the Karagwe-Ankole Belt-KAB that spans Burundi, Rwanda, Southwest Uganda, and North West Tanzania [11]. According to Tack et al. [11], Karagwe-Ankolean Belt and Kibaran Belt comprise what has been described as the intracontinental Central Africa Mesoproterozoic Belt which is around 1300km long across the Central African Congo craton. This belt trends NESW and extends from the Angola-Zambia-Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) border triple junction through Katanga, Kivu- Maniema in DRC, Burundi, Rwanda, SW Uganda, and NW Tanzania. The Mesoproterozoic Belt was subdivided into 2 parts) due to a clear discontinuity marked by the NW trending Paleoproterozoic Rusizian terrain that is in structural continuity with the Ubendian shear belt (Figure 1). The Gatumba area is situated in western Rwanda, Ngororero district. This region is geologically made of an alternation of metapelites of the Mesoproterozoic age and quartzites. The regional metamorphic grade is described to be in general low-grade greenschist metamorphism [12]. On a very local scale, minerals like biotite, andalusite and actinolite are found [13], which could indicate a higher metamorphic grade (Figure 2).

Figure 1:Sketch map of the Kibaran Belt (KIB) and Karagwe-Ankolean Belt (KAB) separated by the Palaeoproterozoic Ubendian Belt [11].

Figure 2:Simplified geological map of the Gatumba area. The location of the Gatumba area is indicated with a rectangle [12].

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in the Western province, Ngororero District, Gatumba sector. One of the methods used is the site visit at Ngororero Mining Company (NMC) which was purposely selected due to environmental issues caused by mining activities that are easily seen in this region such as dirty water, dust in the air during blasting, gas emissions, and mine accidents. A questionnairebased interview was conducted with company leaders to know the baseline and the general historical background of this cassiterite and coltan mining company. Some workers, man powers, and people around mine were also interviewed to gain information on the environment. Collected information was the key to identifying the environmental and health challenges brought by NMC mine operations. In this questionnaire-based interview, I was equipped with different tools such as a questionnaire containing different environmental impacts and different diseases which are known to affect mining workers worldwide as referred to Donoghue [5], a pen, a mobile telephone, and a laptop with Microsoft excel 2016 for making different graphs. Secondary data were also collected from Rwanda Mines, Petroleum and Gas Board (RMB) and also from Ministry of Emergency Management (MINEMA), these data show clearly the injuries and near misses that occurred in a given period due to mining and other related activities. Secondary data were also obtained from different literature talking about mining and waste management in Rwanda and the whole world in general.

Results and Discussion

Stages of mining

As discussed before, mining refers to the activity, occupation, and industry concerned with the extraction of minerals on the Earth. This resulted in the creation of the mining business which is defined as a technically and organizationally separated group of means that directly serve the exploitation of minerals from the deposit, including excavations, constructed objects, and the related technological objects and processing installations [14]. In the mining chain for the minerals industry, different stages required can lead to different environmental destruction or degradation depending on the activities being carried out. Here let us take a look at different mining stages, possible environmental issues, their causes, and consequences.

Exploration stage: For a mining project to commence, the owners must first know the quality, value, and extent of the ore deposit. Gathering information about the location and extent of mineral deposits is obtained through this first phase of mineral exploration. Mineral exploration is defined as the series of getting information about the mineral potential of a given area. The exploration stage involves field visits, geologic modelling, drilling, and sample collection. This stage leads to environmental degradation since it requires drilling, there is the need of clearing wide areas of vegetation, and this earth removal may lead to deforestation, noise, and vibration which destabilize the natural habitat resulting in wild animals relocation as well as erosion and landslide, there is also air contamination and alteration of original soil profiles [15].

Development stage:If the mineral exploration stage proves the existence of ore mineral deposits sufficient enough to be mined for economic profit that is when the mining owners decide to plan for the mine development. This stage involves the construction of required mining infrastructures such as access roads either to provide equipment and supplies to the mine site or to transport out processed materials and ores, site preparation and clearing since most mines are located in remote, undeveloped areas, may need to begin by clearing land for the construction of staging areas that would house project personnel and equipment, underground tunnels, electricity channels, ground preparation, and water channels construction, these are all the activities undertaken in this stage and they can have substantial environmental impacts, especially if access roads cut through ecologically sensitive areas or are near previously isolated communities. These activities also lead to deforestation, land degradation, water, and air pollution, and wildlife destabilization as the impacts on the surrounding environment.

Production and processing stage:After the construction of required infrastructures such as access roads, site preparation, offices, electricity, and water facilities, mining activities related to production may begin to be carried out. This stage involves the removal of the overburden to gain access to the ore deposit. After an overburden removal by the mining company, the mineral ore is extracted using specialized heavy equipment and machinery, and processing ore bodies to obtain the final concentration to be brought to the market. Drilling and blasting activities which lead to ground vibration, groundwater pollution, water source destabilization, air pollution through emission of dust and toxic gases from blasting activities, and human-animal accidents due to flying rocks are common environmental threats of this stage. Mineral processing produces different wastes and if they are not well managed, they may lead to water pollution and soil degradation. Mineral processing is the process of separating valuable minerals (commercially valuable) from gangues (tailings or those that are not commercially valuable). During this stage, mining companies need the proper way of tailing disposal since even high-grade mineral ores consist almost entirely of non-metallic materials and often contain undesired toxic metals (such as cadmium, lead, and arsenic) [2]. The processing process generates high-volume waste called tailings, and these are the residues of an ore that remains after it has been processed and the desired metals (valuable minerals) have been extracted. According to Ronaldo [16], If there is the extraction of a few hundred million tons of mineral ore in a certain mine, then the mine project will generate almost the same quantity of tailings. The way a certain mining company disposes of high-volume toxic waste material is one of the questions that determine whether a proposed mining project is environmentally acceptable [17]. Poor tailing disposal leads to different environmental impacts including contamination of groundwater beneath these facilities and surface waters, especially when the tailings contain toxic substances, they can percolate through the ground and pollute groundwater, and others can run on the surface as runoff and pollute surface water.

Mine reclamation:Mine reclamation, also known as mine closure, is the process of rehabilitating or repairing the damage caused by mining activities. This process of mine reclamation is done once mining is completed, but the planning of mine reclamation activities occurs before the commencement of any mining activity. Mine abandonment or decommissioning may result in similar significant environmental impacts, such as soil and water contamination [15].

Environmental and social impacts of mining activities

Mining activities have many environmental and social impacts, and many authors have written about environmental and social impacts of mining activities in different parts of the world. Let’s summarize some of what different authors have written about this topic. According to Haddaway et al. [15,17-21], the Environmental and social impacts of mining activities can be summarized by looking on what is being impacted as follow:

Impacts on water resources:The most significant impact of a mining project in Rwanda is its effects on water quality and the availability of water resources within the project area. More research’s key question is to determine whether surface and groundwater supplies will remain fit for human consumption and whether the quality of surface waters in the project area will remain adequate to support native aquatic life and terrestrial wildlife [17]. Since a large area of land is disturbed by mining activities and large quantities of soil and other materials are exposed at sites, erosion can be a major concern at mining sites. Consequently, erosion control must be considered from the beginning of operations through the completion of reclamation. Erosion may result in significant loading of sediments and may introduce chemical pollutants to nearby water bodies.

Impacts of mining activities on air qualityIn mining activities, airborne emissions occur during every stage of the mining cycle, but especially during the exploration of minerals, development of mine infrastructures, construction of the mine, and operational activities. Mining operations produce large amounts of material and waste piles containing small size particles that are easily dispersed by the wind. The main source of air pollution in mining operations is known to be the airborne dust matter transported by the wind as a result of the excavation activities, drilling and blasting, transportation of materials, wind erosion more often in an open-pit mine, and emissions from mobile sources as well as stationary sources. The other source is the gas emission derived from the combustion of fuels in stationary and mobile sources (such as cars, drilling machines, and jackhammers), explosions from blasting, and mineral processing. Once pollutants enter the atmosphere, they undergo physical and chemical changes, and they can cause serious effects on people’s respiratory systems and the environment.

Impacts of mining projects on wildlife:Due to vegetation and topsoil removal resulting from mining activities, affects the environment and associated biota through, the displacement of fauna, the release of pollutants, and the generation of noise [17]. The survival of these species can depend on soil conditions, local climate, altitude, and other features of the local habitat. Mining causes direct and indirect damage to wildlife. The impacts originate primarily from disturbing, removing, and redistributing the land surface. Some impacts are short-term such as the destruction or displacement of species in areas of excavation and they are confined to the mine sites; others may have far-reaching, long-term effects. If streams, lakes, and ponds, which are the host of aquatic habitats, are filled or drained, fish and other aquatic animals are severely impacted. Food supplies for predators are reduced by the disappearance of these land and water species [15]. Generally, the habitat requirements of many animal species do not permit them to adjust to changes created by land disturbance. These changes reduce living space. Mining projects usually result in habitat fragmentation and this Isolation may lead to the local decline of species or genetic effects such as inbreeding. Species that require large patches of forest simply disappear.

Impacts of mining projects on soil quality:In a broad range, mining activities are known to contaminate the soil. Agricultural activities near mines are mostly affected by mining activities. According to the European Union, mining operations routinely modify the surrounding landscape by exposing previously undisturbed earthen materials. When the exposed soils are eroded, and also the erosion of extracted mineral ores, tailings, and other fine material in waste rock piles can result in sediment loading to surface waters and drainage ways. In addition, spills and leaks of hazardous materials and the deposition of contaminated windblown dust can lead to soil contamination. Human health and environmental risks from soils generally fall into two categories namely: Contaminated soil resulting from windblown dust and soils contaminated by chemical spills and residues. The amount of dust suspended in the air (fugitive dust) can cause significant environmental problems at mine sites. The inherent toxicity of the dust depends upon the proximity of environmental receptors and the type of ore being mined. Within these areas of impact, fugitive dust may result in damage to vegetation, agriculture, and humans [18]. Soils contaminated from chemical spills and residues at mine sites may pose a direct contact risk when these materials are misused as fill materials, ornamental landscaping, or soil supplements. The mining activities can also result in the loss of cultivated fertile soil.

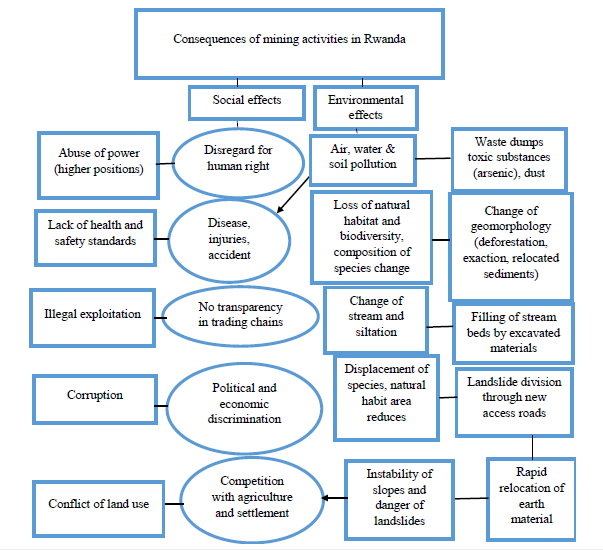

Figure 3:Major consequences of mining activities in Rwanda [21].

Impacts of mining projects on social values and human health:Generally, Mineral development can create wealth, but it can also cause considerable disruption. Mining projects may create jobs, roads, and schools, and increase the demands for goods and services in remote and impoverished areas, but the benefits and costs may be unevenly shared. If communities feel they are being unfairly treated or inadequately compensated, mining projects can lead to social tension and violent conflict [19]. In some areas, Environmental Impact Assessments can underestimate or even ignore the impacts of mining projects on local people. Communities feel particularly vulnerable when linkages with authorities and other sectors of the economy are weak, or when environmental impacts of mining (soil, air, and water pollution) affect the subsistence and livelihood of local people. Records from the International Labor Organization (ILO) [20] show that 160 million employees suffer from work-related illnesses, and 270 million from work-related injuries while around 2 million fatalities are recorded every year due to work-related diseases including respiratory illnesses, musculoskeletal, Noise-Induced Hearing Loss (NIHL), work-related intoxication, cancers and injuries (Internal Labor Organization (ILO), [20]). According to ILO, this sums to 4% of the annual GDP, the ILO records continue showing that due to the lack of proper reporting of work-related accidents and hazards in developing countries, more than 80% of the global labour force facing work-related issues are found in these countries. This results in employees suffering from hurt, and gloom as well as their families, on the other hand, the employers will also be affected since there will be a decrease in production, the quality of the product as well as the overall image of the organization (Figure 3).

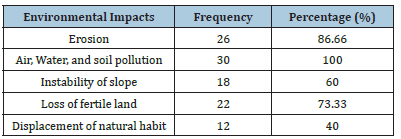

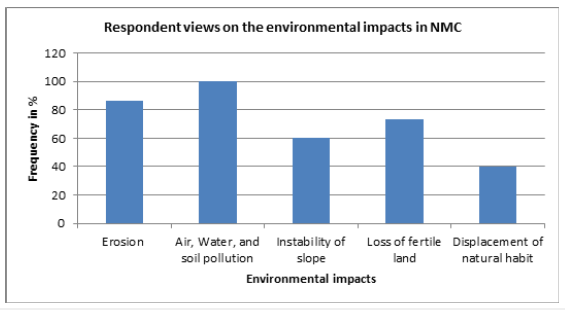

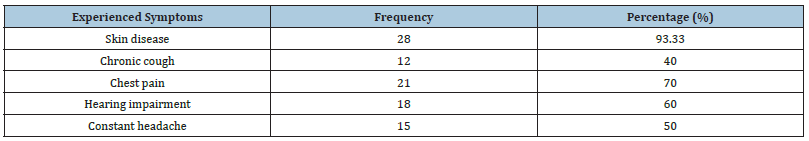

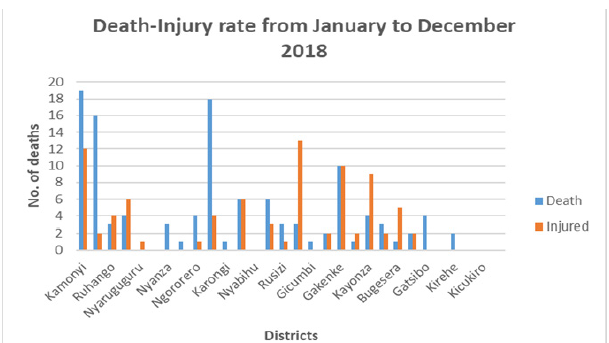

Mining and its environmental impacts on Ngororero Mining Company

As a result of the questionnaire-based interview, much information was gathered, and the staff explained the historical background of NMC where operations were started in 2007. The research went ahead by interviewing the mineworkers at Ngororero Mining Company and the people living near the mine by asking them what mine impacts on the nearest people. This study emphasized questioning people about the problems related to the environmental impacts that might be caused by mining activities in this area and the purpose was to get information on how miners respond to the environmental impacts caused by mining activities in this area and also to know the health disease caused by mining activities in this area. 30 people have been contacted and interviewed and the results are summarized in the following table, among 30 people contacted, 26 of them have witnessed that mining activities in this area cause soil erosion, and all 30 people have confirmed that mining activities lead to air, water, and soil pollution, only 16 have confirmed that the mining activities lead to slope instability, 22 out of 30 responded that the activities lead to loss of fertile land while only 12 out of them have confirmed the displacement of natural habitat due to mining activities (Table 1), (Figure 4). The result from the interview with miners on the health disease caused by mining activities is shown in Table 2. This interview was conducted with miners from different departments (underground working, processing plant) and they were asked if they have had any of the following diseases. Among 30 mine workers contacted, 28 people have had a skin disease caused by mining activities at least once, 12 out of 30 have been affected by chronic cough, 21 out of 30 had chest pain due to mining activities and most of them are those who practice drilling and blasting activities, 18 for hearing impairment and 15 out of 30 for constant headache (Figure 5).

Table 1:Respondent’s frequency of environmental impacts in NMC.

Figure 4:Respondent views on the environmental impacts of NMC.

Table 2:Respondents’ health effects experienced due to mining activities.

Figure 5:Respondents’ health effects experienced due to mining activities.

Figure 6:Exposed tailing dams in NMC which are not well managed.

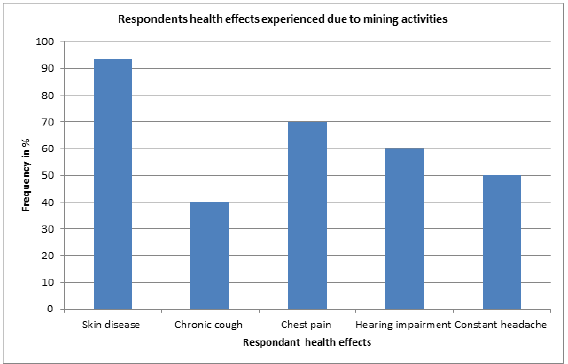

The respondents have also been asked about what they think might be the causes of different impacts and their main answers were related to lack of safety knowledge, they do not have enough training about health and safety in mine and many of them did not attend schools, the absence of preliminary risk assessment before the start of underground activities, suitable high visibility attire, limit to the number of employees who entered the mine tunnels at a time, standardization in term of mine tunnel size, the record of hazards and incidents at the mine site, exit route from the primary access to the mine tunnel, first aid team and room, incident report form and company policy on Occupational Health and Safety (OHS), as well as the fact that there is no training and work for miners on health and safety and ventilation parameter measurement are the characteristics of the studied area. From the observation made to the field, the environment surrounding NMC is not well protected, for example in this region you can see tailing dams that are not well managed (Figure 6). The use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs) is at a lower level in this company, you can see the miners in underground workings without protective helmets and barefoot, considering the safety practices are still low, the fact of not wearing some protective equipment (Figure 7) is a dangerous problem. According to the Rwanda Mines, Petroleum and Gas Board, the mine accidents in the country (Rwanda) from January to December 2018 resulted in 117 fatalities, 85 injuries, and a total number of 53 near misses. Kamonyi district was recorded to be the one with many fatalities (19) followed by Rutsiro district (18); Muhanga district (16) and Gakenke district (10) (Table 3), (Figure 8).

Figure 7:Some miners go to work with no personal protective equipment.

Table 3:Mine accidents in Rwanda from January to December 2018.

Figure 8:Death-injury rate caused by mining activities per district from January to December 2018.

According to [22], the major challenges to the Rwandan mine

safety (Occupation Health and Safety) that is responsible for

increasing mine hazards are known to be:

a. The Rwandan Mining sector is dominated by artisanal

Mining.

b. Lack of accountability: As the artisanal miners and

workers themselves are not known to the Company, there is

little accountability for their practices. Risks are significant

in the absence of systems for accounting for persons working

underground, undercutting of weak rock or soil, work under

the influence of drugs or alcohol, and many more.

c. Difficulty controlling and managing activities.

d. Illegal Mining: illegally collecting minerals is a big

challenge in terms of ensuring their safety, and

e. Shortage of workforce trained in Occupation Health and

Safety.

To effectively tackle the mine safety issue, there should be shared responsibility involving local leadership, security organs, mining entities, and responsible government institutions. The strategy developed by the Rwandan government to ensure the policy of maintaining OHS policy at the company level includes developing the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) policies and guidelines for small scale mines in Rwanda, instituting the system to inspect the OHS on the Mining Sites: To strengthen inspection of mining sites, there are now on average, two workers deployed to check mining activities in each district. They are collaborating with labour inspection officers employed by the Ministry of Public Service and Labour (MIFOTRA) to make timely assessments and reports, and the suspension of the mining license for those who fail to comply with the law of OHS: An employer has the responsibility to make sure that workers are safe at work [22].

Conclusion and Recommendation

Conclusion

This study has revealed that the mining activities of Ngororero Mining Company contribute highly to environmental pollution. From different methodologies adapted, many results indicate that this area causes the majority of problems like noise, water and soil pollution, erosion, displacement of natural habit, and the instability of slope respectively. And due to the results from the interview with miners also in this area, there are health effects on the miners caused by mining activities like skin diseases, chest pain, chronic cough, hearing impairment, and constant headaches. Safety accidents are persisting in this region and our country in general and new causes are being discovered every day. 53% of the fatalities in 2018 were due to the collapse of the tunnel while 48% of the fatalities in the first half of 2019 were also due to the collapse of the tunnel. The safety status of the mines visited as well as other sites in general is still at a low level and needs intervention. Compliance with the established environmental law is still very bad and people, both the employer and employees, still have much attention to production rather than their health and safety. By all means and obtained results, it is without a doubt that more intervention is highly needed [22].

Recommendation

Ngororero Mining Company (NMC) is recommended to manage tailings by storing them in a good way by avoiding tailings runoff into soil and streams as ways to mitigate and reduce the impacts of soil and water pollution, and to personnel protective equipment on their workers to reduce these health effects. The mine should establish its occupational health and safety policy and put in place punishments for those who violate it. Besides, the company should also explain to all the workers both those who work underground and others about the national safety standards and regulations and encourage them to respect and comply with them, communicate the policy, roles and responsibilities, procedures, and hazard incidence, and Implement Safe Working Systems including those related to training and sensitization needed to build capacity and improve safety attitudes as well as preventative maintenance, incident response and reporting, early and safe return to work, workplace inspection, and monitoring and evaluation. On the part of the government, the inspections should be emphasized and strengthened; and some standard knowledge should be required for someone to be part of the occupational health and safety committee and to strengthen the environmental protection in Rwanda that requires sustainable measures against the action of certain mining companies which do not comply with the environment.

References

- (2019) Rwanda Development Board, Rwanda.

- Rupert C, Mitchell P (2014) Evaluation of mining revenue streams and due diligence implementation costs along mineral supply chains in Rwanda.

- NISR (2019) Rwanda natural capital accounts-Minerals resource flows. Kerala, India.

- Rukazambuga D (2008) Sustainable restitution/recultivation of artisanal tantalum mining wastelands in Central Africa- a pilot phase. Etudes Rwandaises, pp. 5-6.

- Donoghue AM (2004) Occupational health hazards in mining: An overview. Occup Med (Lond) 54(5): 283-289.

- Doret B, Freek C (2015) Occupational health and safety considerations for women employed in core mining positions. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 13(1).

- Antoci A, Paolo R, Ticci E (2019) Mining and local economies: dilemma between environmental protection and job opportunities. Sustainability.

- Ahmad I, Sattar A, Nawaz A (2016) Occupation health and safety in industries in the developing world. Gomal Journal of Medical Science, pp. 223-228.

- REMA (2012) Guidelines for environmental impact assessment (EIA) for mining projects in Rwanda.

- Ndikumana JD, Anthony B, Adayemi OG (2019) Neoproterozoic rare element pegmatites from Gitarama and Gatumba areas, Rwanda: Understanding their Nb-Ta and Sn mineralisation. Open Journal of Geology 9(13): 1069-1083.

- Tac L, Wingate MTD, Waele BD, Meert J, Belousova E, et al. (2010) The 1375 Ma “Kibaran event” in Central Africa: Prominent emplacement of bimodal magmatism under extensional regime. Precambrian Research 180(1-2): 63-84.

- Dewaele S, Kunst FH, Melcher F, Sitnikova M, Burgess R, et al. (2011) Late Neoproterozoic overprinting of the cassiterite and columbite-tantalite bearing pegmatites of the Gatumba area, Rwanda (Central Africa). Journal of African Earth Sciences 61(1): 10-26.

- Gérards J (1965) Geology of the Gatumba region, bulletin you service geologique Rwandaise. Scientific Research: An Accademic Publisher 2: 31-42.

- Odoh CK, Kalu AU, Francis A (2017) Environmental impacts of mineral exploration in Nigeria and their phytoremediation strategies for sustainable ecosystem. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research 17(3).

- Haddaway NR, Steven JC, Pamella L, Biljana M, Annicka EN, et al. (2019) Evidence of the impacts of metal mining and the effectiveness of mining mitigation measures on social-ecological systems in Arctic and boreal regions: A systematic Map Protocol. Environ Evid 11(1): 30.

- Ronaldo SD (2016) Excellence in mining: Creativity & practicality insights, perspectives and good practices.

- Norgate WJ (2000) Overview of mining and its impacts: Life cycle assessment of copper and nickel production. In Norgate, Guidebook for Evaluating Mining Project. EIAs Proceedings, Minprex, pp. 133-138.

- Arpacıoğlu CB (2003) Estimation of fugitive dust impacts of open-pit mines on local air quality - a case study: Bellavista gold mine, Costa Rica. 18t" International Mining Congress and Exhibition of Turkey-IMCET pp. 975-395-605-3.

- Eggert RG (2001) Mining and economic sustainability: National economies and local communities. Minerals and Sustainable Development, Colorado school of mines, US.

- Internal Labor Organization (ILO) (2015) Global trends on occupational accidents and diseases. Switzerland.

- Jürgen R, Diderot N (2018) STRADE: Country case studies: Rwanda and Democratic Republic of Congo.

- Drechsler B, Jennifer H, Manfred W (2010) An occupational safety health system for small scale MINES in Rwanda.

© 2023 Nsengiyumva Cedrick. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)