- Submissions

Full Text

Associative Journal of Health Sciences

Does the Fear of Needles Influence Jamaicans’ Willingness to be Vaccinated against COVID-19?

Paul Andrew Bourne1*, Diandre Allen2, Sephora Crumbie2, Tallia Scille2, Shanise Simpson2, James Fallah3, Calvin Campbell4, Clifton Foster5, Caroline McLean2, Dian Russell Parkes2, Tabitha Muchee6 and Devon Cross field7

1Department of Institutional Research, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

2Department of Nursing, Northern Caribbean University, Mandeville, Jamaica

3Department of Dental Hygiene, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

4Department of Mathematics and Engineering, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

5Department of Biology, Chemistry, and Environmental Sciences, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

6Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

7Medical Epidemiologist and Educational Administrative Consultant, Jamaica

*Corresponding author: Paul Andrew Bourne, Acting Director of Institutional Research, Northern Caribbean University, Mandeville, Manchester, Jamaica

Submission: January 22, 2022;Published: March 01, 2022

ISSN:2690-9707 Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

Introduction: As of November 21, 2021, the vaccination rate in the world is 55% (fully vaccinated,

43%) compared to 22% in Jamaica (17% fully vaccinated), 70% in the United States and Canada, 66%

in Latin America, Asia-Pacific (64%), Europe (62%), Middle East (45%), and 9.7% in Africa. A variable

proportion of each country’s population is delaying or avoiding vaccination, which may hamper the

success of vaccination programmes. The frequency of needle injections averaged from 2-11 per person

each year in 10 major regions globally in a study conducted by the World Health Organization [1-10].

Aim: To explore whether the fear of needles influences Jamaicans’ willingness to be vaccinated?”

Methods and materials: The study used an explanatory web-based cross-sectional design. A

standardized questionnaire instrument consisting of fifteen closed-ended questions was disseminated

via WhatsApp, Facebook, and face-to-face interaction in the fourteen parishes. The Statistical Packages

for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 25 for Windows 27.0 provided data analysis (Table 1).

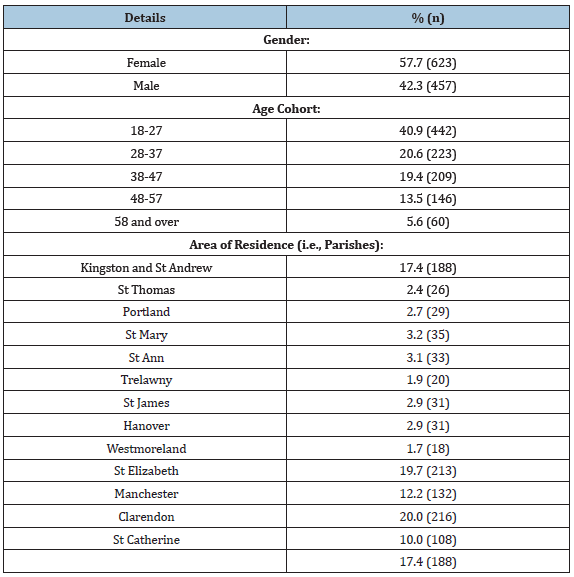

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the sampled respondents, n=1,080.

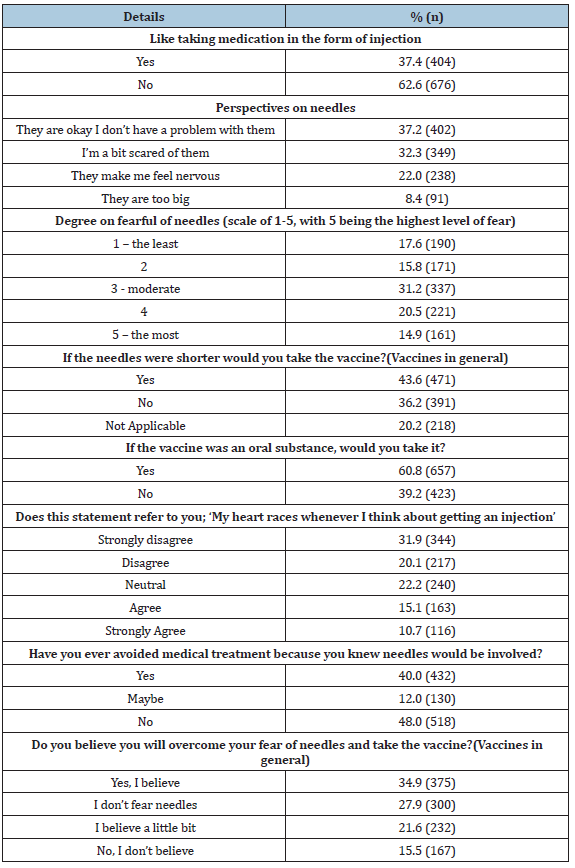

Findings: Most of the respondents were females living in Clarendon who were hesitant to take the

vaccine due to trypanophobia. Of the total respondents, 62.6% (n=676) avoided medication requiring

administration through needles. The majority of the respondents (31.2%, n=337) was three on a scale

of 1-5 (with 5 being the highest level of fear). Most respondents (43.6%, n=471) answered “Yes” when

asked, “If the needles were shorter would you take the vaccine?” When asked if the following statement

referred to the: “My heart races when I think about getting an injection”, most of the respondents (31.9%,

n=344) agreed. Age, fear of needles, and willingness to accept oral vaccination accounted for 21.6% (i.e.,

Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in vaccination status (-2Ll=744.023; Omnibus test of Model coefficients:

χ2(8)=117.109, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow test: χ2(8)=10.750, P-value = 0.216) [11-13].

Conclusion: The influence of trypanophobia on COVID-19 vaccination rates in Jamaica must

be considered when formulating future public media strategies, policymakers’ approach, and civic

responsibility in reducing vaccine hesitancy among the population. Therapeutic healthcare provider and

patient interactions are pivotal in increasing the patient’s confidence, willingness toward treatment, and

the strength to overcome trypanophobia (Table 2).

Table 2:Respondent’s views on needles/injections, n=1,080.

Keywords: COVID-19; Fear of needles; Injection; Needle; Needle phobia; Trypanophobia; Vaccine acceptance; Vaccine hesitancy

Background

The initial report of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) occurred on December 31, 2019, following pneumonia cases of unknown origins in Wuhan city, China (World Health Organization (WHO). The virus was declared a global health emergency on January 30, 2020 (WHO). Holder of the New York Times indicated that as of November 21, 2021, the vaccination rate in the world is 55% (fully vaccinated, 43%) compared to 22% in Jamaica (17% fully vaccinated), 70% in the United States and Canada, 66% in Latin America, Asia-Pacific (64%), Europe (62%), Middle East (45%), and 9.7% in Africa. These statistics indicate that a variable proportion of the population in each country are delaying or avoiding vaccination, which may hamper the success of vaccination programmes [13-21].

A significant number of persons continue to be diagnosed with

the COVID-19 virus. A more substantial number of individuals died

from the COVID-19 due to the initial lack of knowledge of how to

treat such a virus, making vaccines more critical. The fear of getting

vaccinated may be hindering the current uptake in Jamaica [21-26].

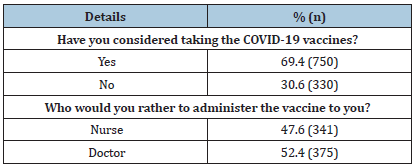

A renowned medical doctor, Professor Denise Eldemire Shearer,

postulated that trypanophobia (i.e., the fear of needles or needle

phobia) is accounting for some per cent of COVID-19 vaccine

hesitancy among the Jamaican population, which is also the case

across the globe, and this extends to children (Table 3). A search

of the literature revealed no empirical support for the perspective

of Eldemire, and this means that the society continue to operate and plan in ignorance for the pandemic. Hence, this study seeks to

answer the following research questions:

A. What are the reasons for Jamaicans current unvaccinated

status?

B. Is the vaccination process delayed due to the fear of needles?

and

C. What is the profile of those who fear needles in the vaccination

process?

Table 3:Issues on COVID-19 Vaccines, n=1,080.

H0: No statistical relationship exists between the fear of needles and considering taking the COVID-19 vaccine.

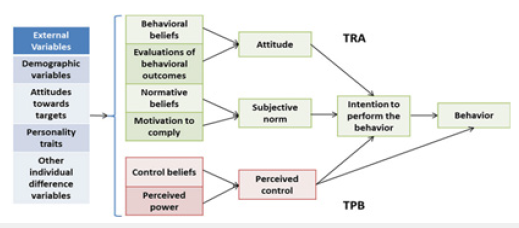

To contextualize the current study and answer the research question, a theoretical framework (i.e., Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior) was developed to guide and better understand COVID-19 hesitancy as a result of trypanophobia in Jamaica [26-39].

Theoretical framework

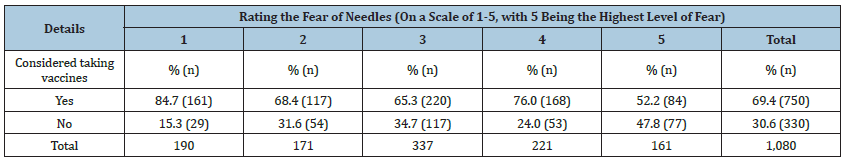

Globally, varying views exist on the vaccination process and the COVID-19 virus, leading to world leaders implementing additional measures. Social distancing, frequent hand washing, and education were some of those measures (Table 4). Despite the plethora of current information, individuals still have mixed feelings about vaccination. These feelings range from fear of needles to misunderstanding of information. A theoretical framework that addresses the study constructs is warranted to explore further the “fear needles” and their influence on vaccinations. This current study uses a theoretical framework reflecting the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior that aided the researchers in better assessing these phenomena (Figure 1).

Table 4:A cross-tabulation between the fear of needles and considering taking the COVID-19 Vaccine, n=1,080.

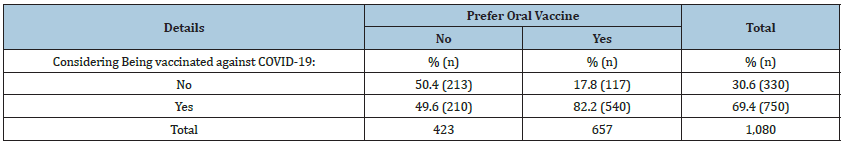

H0: There is no statistical association between considering being vaccinated against COVID-19 and preferring oral vaccines.

Figure 1:Reason action theory/theory of planned behaviour.

According to Rural Health Information Hub (2018), the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior explain the association of beliefs and behaviour and implies that a person’s health behaviour is determined by their intention to perform a behaviour. Attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control collectively influences an individual’s behavioural intentions. An individual’s attitude toward the behaviour and the subjective norms affects their intention to perform a behaviour. However, subjective norms result from the social and environmental surroundings and an individual’s perceived control over the behaviour (Table 5). Generally, a positive attitude and positive subjective norms result in greater perceived control and increase the likelihood of intentions governing changes in behaviour. The theory clarifies health behaviours, planning, implementing health promotion and disease prevention programs [39-44].

Table 5:A cross-tabulation of considering being vaccinated against COVID-19 and prefer oral Vaccines, n=1,080.

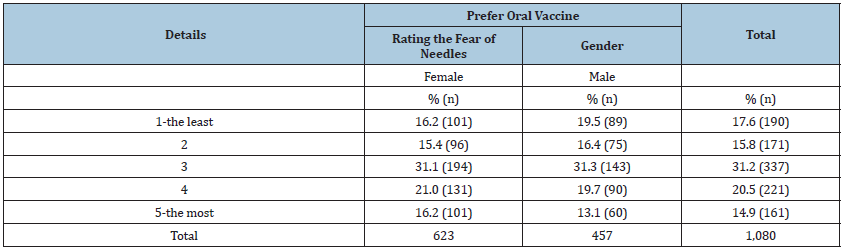

Furthermore, subjective norms describe the behaviours of healthcare providers, patients, care providers, and others in the community. Therefore, these theories provide a framework for answering this current study’s research question, “Does the fear of needles influences Jamaican’s willingness to be vaccinated?” An individual’s decision depends on their attitude towards a particular situation, whether positive, negative, or neutral Tables 6-8. Using the theoretical framework (Figure 1) to address the research question, we anticipate that individuals will consider the vaccination process negative or positive. Furthermore, if individuals believe that the outcome of taking the vaccine is beneficial, they will have a positive attitude. If they believe the vaccine is not essential and has undesirable effects, they will react negatively.

Table 6:A Cross-tabulation between the fear of needles and Gender, n=1,080.

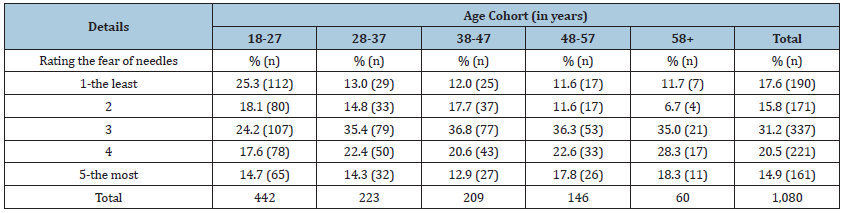

H0: Older respondents are less likely to fear needles than younger respondents.

Table 7:A cross-tabulation of rating the fear of needles and age Cohort, n=1,080.

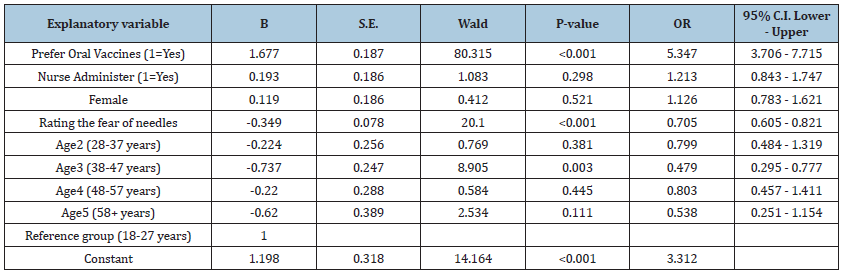

Table 8:Binary logistic regression of vaccination status of Jamaica by selected explanatory Variables.

OR denotes the odds ratio.

References

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50(2): 179-211.

- Andrews N, Tessier E, Stowe J, Gower C, Kirsebom F, et al. (2022) Duration of protection against mild and severe disease by Covid-19 vaccines. New England Journal of Medicine 386(4): 340-350.

- Appleby J (2021) Fear of needles may keep many people away from Covid vaccines: Images of large Covid-19 needles hands are on billboards, bus stop posters and all-over social media.

- Baccolini V, Renzi E, Isonne C, Migliara G, Massimi A, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Italian university students: A cross-sectional survey during the first months of the vaccination campaign. Vaccines 9(11): 1292.

- Brown L, Gopal L (2021) Covid vaccine and needle phobia: It feels like the world is ending.

- Carey CL, Harris LM (2005) The origins of blood‐injection fear/ phobia in cancer patients undergoing intravenous chemotherapy. Behavior Change 22(4): 212-219.

- Carmin C (2019). How to overcome your fear of needles.

- Cavaleri M, Enzmann H, Straus S, Cooke E (2021) The European medicines agency's EU conditional marketing authorisations for COVID-19 vaccines. The Lancet 397(10272): 355-357.

- Cemeroglu A, Can A, Davis A, Cemeroglu O, Kleis L, et al. (2015) Fear of needles in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus on multiple daily injections and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Endocrine Practice 21(1): 46-53.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2022) Needle fear and phobia-Find ways to manage. CDC, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- Davis LA, Ku BS, Griffin B, Fields JM (2013) Prevalence of needle phobia in patients with difficult venous access. Academic Emergency Medicine 20(5): S141.

- DeNicola E, Aburizaize O, Siddique A, Khwaja H, Carpenter DO (2016) Road traffic injury as a major public health issue in the kingdom of saudi arabia: A review. Frontiers in Public Health 30(4): 215

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, USA.

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I (2010) Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Taylor & Francis, New York, USA, pp. 538.

- Freeman D, Lambe S, Yu LM, Freeman J, Chadwick A, et al. (2021). Injection fears and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Psychological medicine 1-11.

- Fritscher L (2021) What is trypanophobia?

- Hackman CL, Knowlden AP (2014) Theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behavior-based dietary interventions in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 5: 101-114.

- Hamilton JG (1995) Needle phobia: a neglected diagnosis. Journal of Family Practice 41(2):169-75.

- Holder J (2021) Tracking coronavirus vaccinations around the world. New York Times, New York.

- Hutin YJ, Chen RT (1999) Injection safety: a global challenge. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 77 (10): 787-788.

- Jamaica Observer (2021) Easing vaccine hesitancy requires everyone's help. Kingston: Jamaica Observer, California, USA.

- Legg T (2018) Trypanophobia.

- Loopnews (2017) Needle phobia: Can you overcome a fear of jabs?

- Love A, Love R (2021) Considering Needle Phobia among Adult Patients During Mass COVID-19 Vaccinations. J Prim Care Community Health 12:21501327211007393.

- Lyons R (2021) Fear of needles causing vaccine hesitancy, says Eldemire-Shearer. Kingston: Jamaica Observer, California, USA.

- MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy (2015) Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 33(34): 4161-4164.

- Malcolm X (2016) Trypanophobia- A fear of needles.

- McLenon J, Rogers MAM (2019) The fear of needles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(1):30-42.

- McMurty M (2021) Needle fears can cause COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, but these strategies can manage pain and fear.

- Montaño DE, Kasprzyk D (2008) Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In Glanz K, et al. (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice, Jossey-Bass, USA, pp. 67-96.

- National Library of Medicine. (2021) How to cope with medical test anxiety.

- Ratini M (2021) What to Know About the Fear of Needles (Trypanophobia).

- Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, et al. (2021) Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19).

- Rural Health Information Hub (2018) Theory of reasoned action/planned behavior.

- Sierzega J (2021) Conquering needle phobia for the COVID-19 vaccine.

- Smith G (2021) Needle phobias are preventing some people from getting COVID-19 vaccines. These interventions could help. S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- Sørensen K, Skirbekk H, Kvarstein G, Wøien H (2020) Children’s fear of needle injections: a qualitative study of training sessions for children with rheumatic diseases before home administration. Pediatric Rheumatology 18(1):13.

- Starr M, Poole C (2016) Utilising shared care documents to promote self-care for a patient with trypanophobia. Fresenius Medical Care.

- Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN) (2022) Population statistics. Kingston, STATIN, California, USA.

- S. Department of Health & Human Services (2022) Children’s Mental Health: Needles fear and phobia - Find way to manage.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global research and innovation forum: Towards a research roadmap.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (nd) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

© 2022 Paul Andrew Bourne. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)