- Submissions

Full Text

Associative Journal of Health Sciences

Fear and Prejudice: Does the Fear of HIV Testing Affect Antenatal Care Attendance Among Women in Oyam District, Uganda?

Stefanie A. Joseph1*, Nils Hennig1, Judith Kia2, Ahmed Babu2 and Bob Achura2

1Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA

2Global Health Network (U), Uganda

*Corresponding author: Stefanie A. Joseph, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA

Submission: January 02, 2020;Published: February 24, 2020

ISSN:2690-9707 Volume1 Issue2

Abstract

Introduction: Uganda’s maternal mortality rate (MMR), 343 deaths per 100,000 live births, is one of the highest in the world. Antenatal care can prevent maternal deaths by providing information and health services to mothers. Antenatal care clinics provide HIV testing to reduce transmission and provide early diagnosis and treatment in mothers. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends women attend at least four antenatal care visits during their pregnancy. In Uganda, 6 out of every 10 women attend the four antenatal care visits. This study’s objective was to evaluate whether fear of or prejudice against HIV testing affects antenatal care visit attendance by expectant mothers in the sub-counties of Oyam District.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out among 184 women to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of HIV, HIV testing, and antenatal care. The study population included women from six subcounties in Oyam District, Northern Uganda. Participants completed questionnaires adapted from the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016 to collect information on the attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of HIV and antenatal care visits.

Results: Out of 184 women, 37 (20.1%) feared to test for HIV during pregnancy and 147 women did not fear (79.9%), even if prejudice was displayed. There was no association between the antenatal care visits a woman attended and whether they feared to get tested for HIV (p=0.48). There was no association between the first month of antenatal care attendance and whether there was fear to get tested (p=0.26).

Conclusion: Although HIV stigma is present, testing for HIV does not deter women from attending antenatal care services.

Keywords: Antenatal care; HIV testing; Oyam; Uganda; Maternal health

Background

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, is one of the world’s most serious public health concerns affecting the lives of approximately 37.9 million people worldwide. The virus affects the body’s defenses by weakening the immune system against diseases and infections. In 2018, the prevalence of HIV in Uganda was 6.2% among individuals ages 15 to 64, with 1.4 million people living with HIV [1]. HIV continues to affect the population of Uganda, with approximately 53,000 new infections and 23,000 deaths [2]. Despite HIV testing, counseling, and treatment becoming available, stigma towards HIV is still present. People with HIV withdraw from social contact and do not attend health-promotion activities [3]. Lack of social engagement and utilization of health services can result in poor physical and mental health among these individuals. Stigma can arise from the attitudes of community members. Multiple studies found that community members were unwilling to provide care and support to people living with HIV due to fears of HIV transmission [4,5]. Relatives also display prejudice toward family members of those who have died from HIV-related illness. Stigma against HIV causes relatives to ostracize the children of those who have died, threaten the spouse, or refuse to assist in familial care [4]. Additionally, an HIV infection can cause insecurity and discrimination in the workplace [3]. Individuals who are HIV-positive and unemployed find it difficult to find work or are terminated from their job once they are revealed to be infected [3].

Uganda’s maternal mortality rate (MMR), 343 deaths per 100,000 live births (2015), remains one of the highest in the world. In Oyam, the MMR is 500 per 100,000 live births [6]. HIV can be harmful for mothers, accounting for 19,000 to 56,000 maternal deaths worldwide in 2011 [7]. Among Ugandan mothers, HIV was associated with a 70% increase in the odds of major maternal morbidity [8]. These deaths can arise from direct and indirect causes. Several studies have also suggested that HIV is a risk factor for maternal mortality, since pregnant women infected with HIV have an increased risk of developing puerperal sepsis (especially after cesarean delivery) and abortion-related sepsis [8,9]. HIV testing is offered in antenatal care clinics to detect antibodies, treat HIV in mothers, and prevent mother to child transmission (PMTCT).

Antenatal care can prevent maternal and perinatal deaths by providing information and vital services to mothers for pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period. Antenatal care visits provide services such as blood pressure monitoring and intermittent preventive malaria treatment, in addition to examining the baby’s position and health. Antenatal care services also ensure pregnant women are checked and treated for any harmful conditions that may occur during their pregnancy.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends women attend at least four antenatal care visits during their pregnancy [10]. According to UNICEF in 2018, 86% of pregnant women around the world accessed antenatal care at least once, while only 62% attended four visits [11]. In Uganda, 6 out of every 10 women attend the recommended four antenatal care visits [12]. This study’s objective was to evaluate whether fear of or prejudice against HIV testing affects antenatal care visit attendance by expectant mothers in the sub-counties of the Oyam District. Does HIV testing deter women from attending antenatal care services since there is stigma against individuals living with HIV? Studying this effect can provide information to adjust and improve the current standard of care and increase the number of expectant women who are attending antenatal care services. This study might also provide information on how to make antenatal care services feel safe and comfortable for mothers.

Methods

A cross-sectional study assessing women’s knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of HIV, HIV testing, and antenatal care was conducted. The study population included females from six subcounties in the Oyam District, Northern Uganda. Eligibility criteria included: participants be at least 18 years old, be either pregnant or have at least 1 child, and speak the local language Luo. The sample included 184 participants ages 19 to 63 years old.

Questionnaires were distributed among six randomly selected sub-counties in Oyam. Loro, Iceme, Acaba, Aber, Kamdini, and Oyam Town Council (Oyam T/C) were selected. Antenatal care clinics were randomly selected throughout these sub-counties. Questionnaires were adapted from the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016 to collect information on the attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors of HIV and antenatal care visits. Questionnaires were administered in the local language Luo. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze associations between fear of HIV testing and antenatal care visit attendance.

Results

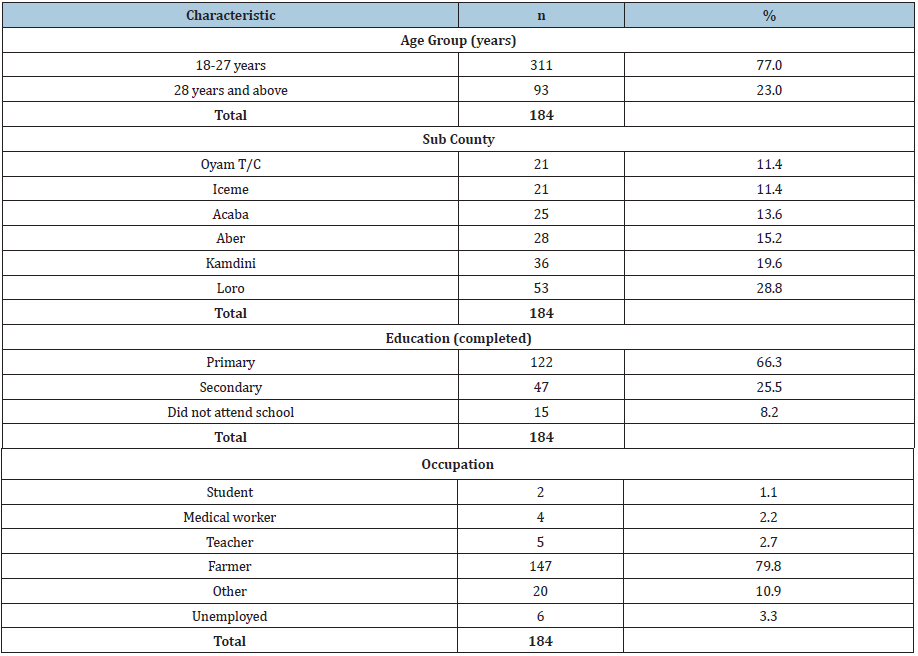

Table 1: Demographics of participants

Table 2: First time women received antenatal care during their most recent pregnancy

Table 3: Number of antenatal care visits attended

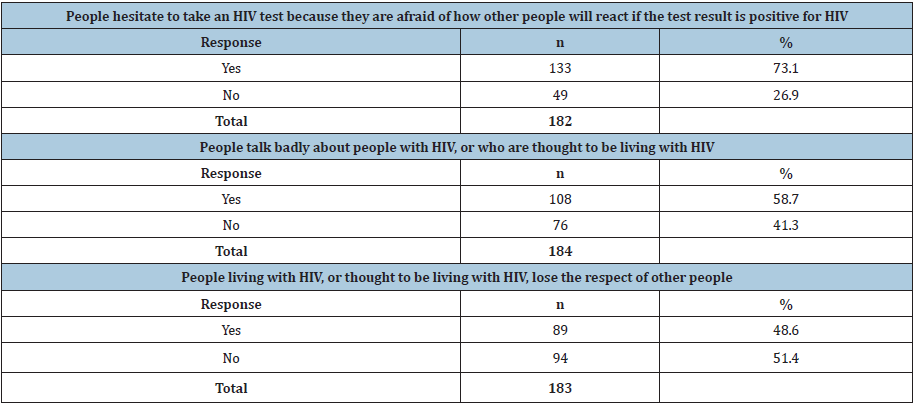

Table 4: Participants’ attitudes on HIV

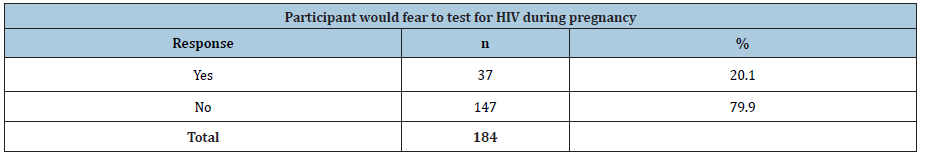

Table 5: Fear of HIV Testing

Table 1 shows 184 women, ages 19 to 63, from six sub counties participated in the study. The median age was 28 years old (IQR=8). A majority of the participants (91.8%) had at least a primary education and 79.8% were farmers. Table 2 shows 14.0% (n=25) of women first received antenatal care less than 3 months into their most recent pregnancy. 40.2% (n=72) of women first received antenatal care at approximately 3 months into their most recent pregnancy. 45.8% (n=82) of women received antenatal care after 3 months into their most recent pregnancy. Table 3 shows 24.3% (n=44) of women attended antenatal care visits 1 to 3 times for their most recent pregnancy, while 75.7% (n=137) attended antenatal care visits 4 or more times. Table 4 shows 73.1% of women think people hesitate to take an HIV test because they are afraid of how other people will react if the test results are positive for HIV. 58.7% of women think people talk badly about people living with HIV or are thought to be living with HIV. 48.6% of women think people living with HIV or thought to be living with HIV lose the respect of other people. Table 5 shows 37 women feared to test for HIV during pregnancy (20.1%) and 147 women did not fear (79.9%), even if they displayed prejudice (Table 4).

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the association between the antenatal care visits a woman attended and whether they feared to get tested for HIV. Fisher’s exact test had a non-significant p-value (p=0.48). Chi-square test was used to assess the association between the first month of antenatal care attendance and whether there was fear to get tested. Chi-square test had a non-significant p-value (p=0.26). Stigma is present among the community, as shown in Table 4, based on a majority of “Yes” responses except for the question regarding losing respect. Although HIV stigma is present, testing for HIV does not deter women from attending antenatal care services.

Discussion

Generally, these results suggest that HIV testing does not discourage women from attending antenatal care visits during their pregnancy. Even though the data indicated that negative attitudes about HIV are still prominent among this population, it is not a cause of deferment. Considering that there were no significant associations between a sense of fear and attendance, other factors play a role in averting women from receiving maternal health care. Studies indicated that maternal education, socioeconomic class of the mother, lack of available resources, and affordability all influence the utilization of antenatal care services [13].

The data of this study show that HIV testing should be encouraged and implemented among antenatal care clinics. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 40% of new HIV infections are transmitted by people who do not know they have the virus [14]. HIV testing can reduce transmission and provide early diagnosis and treatment, therefore improving health outcomes. According to the Republic of Uganda’s Ministry of Health, mother-to-child transmission is the second most common mode of HIV transmission in Uganda, accounting for 18% of new infections. When a mother knows her HIV status, she can begin the recommended antiretroviral interventions and decrease the risk of delivering an infant with HIV. Therefore mother-to-child transmission can be prevented.

HIV education should also be promoted among clinics in Oyam to provide mothers with information on risk factors, prevention measures, and treatment. Knowledge on HIV transmission can help reduce stigma among community and family members of those living with HIV.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations, including a relatively small sample size. There were 184 participants from six sub counties in the Oyam District. The study was cross-sectional and does not account for changes in the participants answers over time. Participant and reporting bias may have been present regarding the women’s responses. Recall bias could have been prevalent among the participants who had trouble remembering how many times they attended antenatal care in the past, especially if there has been a gap in time since they last gave birth.

Conclusion

Antenatal care services are important because they provide information about the mother and child’s health to help ensure a healthy pregnancy. However, women in rural Uganda, such as Oyam, face troubles attending these services. Studies have indicated that the following factors played a role in lack of antenatal care among mothers: high cost of antenatal care services, inadequacy of services, poor access to essential skilled birth attendants, lack of transportation, and overall health worker shortages. Through our study results we have concluded that a fear of HIV testing may not be among these factors. Therefore, even if HIV stigma exists, HIV testing should be encouraged and promoted throughout clinics in Oyam to provide quality maternal health care.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Gulu University and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). Prior to data collection, community leaders consented to include sub-county residents in the study. Upon approval, all participants provided written informed consent to be included in the study and for their information to be used for scientific purposes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available by emailing SJ on reasonable request.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Ministry of Health Republic of Uganda (2016-2017) Uganda Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment UPHIA, Uganda.

- UNAIDS (2019) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, Uganda.

- Monio SM, Tanga EO, Nuwagaba A (2001) Uganda: HIV and AIDS-related Discrimination, Stigmatization, and Denial. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- Asingwire, N (1992) Towards the development of AIDS policy in Uganda. McMaster University Hamilton, ON, Canada.

- Ankrah, EM (1993) AIDS and the urban family: its impact in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Care 5(1): 55-70.

- Massavon W, Wilunda C, Nannini M, Majwala RK, Agaro C, et al. (2017) Effects of demand-side incentives in improving the utilization of delivery services in Oyam District in northern Uganda: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 17(1): 431.

- Lathrop E, Jamieson DJ, Danel I (2014) HIV and maternal mortality. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 127(2): 213-215.

- Nuwagaba B, White M, Okong RT, Brocklehurst P, Carpenter LM (2012) The impact of HIV on maternal morbidity in the pre-HAART era in Uganda. Journal of Pregnancy.

- Moran NF, Moodley J (2012) The effect of HIV infection on maternal health and mortality. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 119: S26-S29.

- Benova L, Dennis ML, Lange IL, Campbell OM, Waiswa P (2018) Two decades of antenatal and delivery care in Uganda: a cross- sectional study using demographic and health surveys. BMC Health Services Research 18(1): 758.

- UNICEF (2019) Antenatal care. United Nations Children’s Fund, USA.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), ICF U (2018) Uganda demographic health survey 2016, Uganda.

- Edward B (2011) Factors influencing the utilisation of antenatal care content in Uganda. The Australasian medical journal 4(9): 516.

- CDC (2019) Ending the HIV epidemic: HIV treatment is prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA.

© 2020 Stefanie A. Joseph. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)