- Submissions

Full Text

Associative Journal of Health Sciences

Doctor-Patient Relationship According the Psychosocial Aspects of Diseases in General Medicine

Jose Luis Turabian*

Specialist in Family and Community Medicine, Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Spain

*Corresponding author:Jose Luis Turabian, Specialist in Family and Community Medicine, Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Spain

Submission: February 25, 2019;Published: August 08, 2019

ISSN:2690-9707 Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

The doctor-patient relationship is keystone of care. This article shows “how it is done” according to the psychosocial aspects of diseases: 1) Doctor-patient Relationship (DPR) in cardiovascular diseases (Is required control of verbal and non-verbal manifestations to transmit security); 2) DPR in arterial hypertension (Focusing on the persuasion that seeks to guarantee therapeutic compliance); 3) DPR in asthma and COPD (Ventilating the patient conflicts); 4) DPR in digestive diseases (The patient usually has feelings of dependence); 5) DPR in psychiatric diseases (Maximizing quiet listening skills); 6) DPR in endocrinological problems (Requires detailed explanations at the cultural level of the pathophysiological mechanisms); 7) DPR in hematological diseases (Take into account the mental stability of the patient during chemotherapy); 8) DPR in cancer (Maintain a clear and permanent communication with the patient); 9) DPR in SIDA (Knowledge of diagnosis and confidentiality); 10) DPR in rheumatic diseases (Being seen as an individual and not as a mere diagnosis, and being believed in regard to pain and suffering); 11) DPR in dermatological diseases (Explanations about the probable cause of the disease and its duration); 12) DPR in neurological diseases (the patient has to know his diagnosis and the evolution of the disease, foreseeing possible emotional reactions, and the doctor-patient relationship is extended to the family environment). Contextualization of the doctor-patient relationship according to the psychosocial aspects of diseases has as much to do with “what is done”, with “how much is done”, and with “how it is done”.

Keywords: Physician-patient communication; Physician-Patient Relations; Psychological Factors; Disease; General Practice; Framework

Introduction

The doctor-patient communication is one of the most essential dynamics in health care. Specifying more, the doctor-patient relationship is a cornerstone of medical care in general medicine. In addition, general medicine/family medicine are defined in terms of relationships, rather than in terms of diseases or technology [1]. The doctor-patient relationship is a complex phenomenon shaped by doctor-patient communication, patient participation in decision-making and patient and physician satisfaction. The transcendence of the doctorpatient relationship is given by the confirmed fact of its influence on the results of health care [2,3]. Among the various benefits that have been described about the doctor-patient relationship, are:

1. Clinical advantages: by increasing knowledge about the patient, facilitates diagnosis and treatment; presents the unique opportunity to study the natural history of the disease; allows to see that the presence of a problem in a family member can be a marker of conflict in another or other members of the same; facilitates the monitoring of the chronically ill.

2. Benefits of medical intervention: evidence has been found of better compliance, satisfaction and recovery of patient information in consultations with a good relationship of trust with patients or consultations focused on the patient (consultations where “the patient is placed first “or there is a relationship of trust between the patient and the provider, or there is a shared support for decision making).

3. Advantages with respect to prevention: it facilitates the implementation of preventive elements.

Public health benefits: it allows transforming actions on populations into actions on individuals

5. Benefits on the health service provided: contributes to the quality of care; favors satisfaction with the service; saves costs to the health system (better use of services, fewer hospitalizations, etc.) [4-10].

However, the doctor-patient relationship is a professional social relationship and, as such, on the one hand it is subject to avatars and the evolution of society, and on the other hand, it is a complex, multiple and heterogeneous relationships that cannot be define in a unique way or generalize a unique concept of relationship [11,12]. That is, there are “many” doctor-patient relationships that are appropriate according to their contexts, which on the other hand may be changing, in addition to this doctor-patient relationship is not monolithic (it is not established in a way and remains constant forever ), but it is different according to different moments or encounters. In addition, because of the above, the doctor-patient relationship is difficult to measure [13,14]. Consequently, the concept of doctor-patient relationship is poorly defined, and the desirable model of doctor-patient interaction has been the subject of controversy and debate in recent years without ever reaching an adequate degree of consensus on how to define and even name it [15]. It can be said, therefore, that there are many ways of understanding, classifying and practicing the doctor-patient relationship [16]. On the other hand, the disease modifies the doctor-patient relationship. When a person who feels sick visits the doctor, and finally he establishes a diagnosis of illness, a change in the doctor-patient relationship occurs as a result of a third factor, the disease. The social judgment is confirmed by the doctor (member of the society) who perceives that something different from what is established as a norm occurs in the patient, which is why he classifies it as an individual different from the others. Therefore, their response in the treatment corresponds to a kind of discrimination and rejection [17].

Usually, doctors assume that the disease once diagnosed must be cured or improved (at least in the somatic sphere), but this is not always true. Only 8% of cases are “cured” in the sense that they do not need successive medical attention. On the contrary, the disease greatly influences the doctor-patient relationship. This field is formed by the personal and social contexts of doctor and patient, including beliefs and symbols. For example, an accident tends to provoke our sympathy, a venereal disease, our repulsion. The family usually incorporates their anxieties into this doctorpatient relationship [18]. Although there is much literature on the topic of doctor-patient relationship, it is surprising how little has been written about the fact that doctor-patient relationship can be different according to the psychosocial aspects of diseases, that is, this relationship can be different in various diseases. In this context, this article aims to show very briefly a panoramic view of the differences in the doctor-patient relationship according to the disease attended from general practitioner

Discussion

The doctor-patient relationship is of great complexity and results from a long process that involves participation and active work of both parties to reach harmony. “It takes two to dance the tango.” So, it is possible that doctors still need to practice some steps [19]. Therefore, the medical-patient relationship can be different according to the psychosocial aspects of diseases. Some examples we have them in:

1. Doctor-patient relationship in cardiovascular diseases

2. Doctor-patient relationship in arterial hypertension

3. Doctor-patient relationship in asthma and COPD

4. Doctor-patient relationship in digestive system diseases

5. Doctor-patient relationship in psychiatric diseases

6. Doctor-patient relationship in endocrinological diseases

7. Doctor-patient relationship in hematological diseases

8. Doctor-patient relationship in cancer

9. Doctor-patient relationship in AIDS

10. Doctor-patient relationship in rheumatic diseases

11. Doctor-patient relationship in dermatological diseases

12. Doctor-patient relationship in neurological diseases

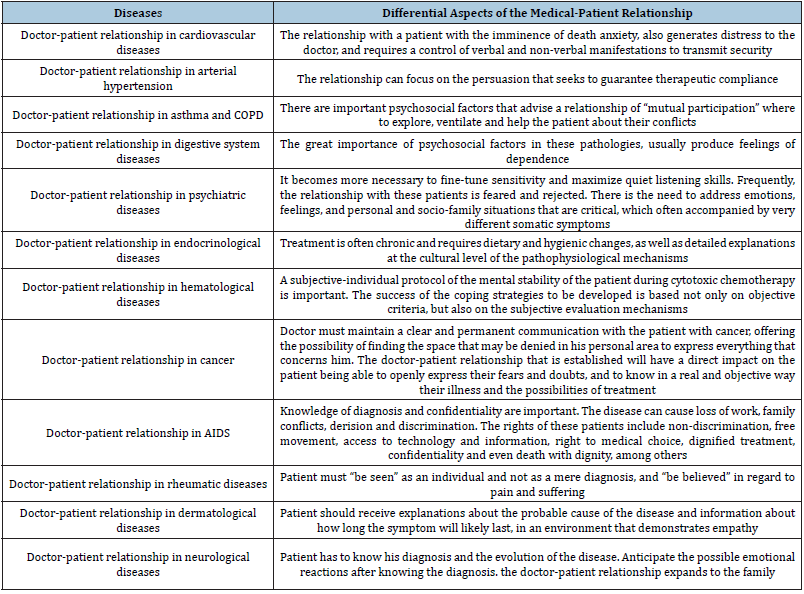

Table 1:Differential aspects of the medical-patient relationship according to diseases.

Doctor-patient relationship in cardiovascular diseases

The long-term link between chronic mental stress, anxiety, depression, and hostility with adverse cardiovascular events has been well established [20]. Lifetime depression and depression around the time of an acute coronary syndrome event have been associated with poor cardiac outcomes. Se ha sugerido that poor sleep quality may be causal or indicate high anxiety/neuroticism, which increases risk to depression and contributes to poor cardiac outcomes rather than depression being the primary causal factor [21]. A substantial proportion of patients have anxiety and depression symptoms after coronary heart disease events, but these conditions are undertreated. These disorders, especially depression, are associated with other risk factors, including educational level, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, unhealthy diet and reduced compliance with risk factor modification [22]. For example, it is described that at the end of the life cycle, in men myocardial infarction occurs more frequently in situations of family conflicts OR that there are familiar patterns of expression of diseases [23]. On the other hand, it has been reported that direct effects of psychological interventions to treat patients with myocardial infarction or revascularization or with diagnosis of angina pectoris or coronary heart disease defined by angiography, improved depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress [24]. All these circumstances can guide the doctor on how to build the relationship. On the other hand, the relationship with a patient with the anguish of imminence of death, also generates anguish to the doctor, and forces a control of the verbal and non-verbal manifestations to transmit security [19].

Doctor-patient relationship in arterial hypertension

It has been described that when the patient has more years of education, more knowledge about hypertension, longer duration of hypertension and beliefs of natural causes, these factors predict a more cognitive representation of the disease in patients, while conversely: fewer years of education, less knowledge of hypertension and beliefs of behavioural causes (eg, diet and exercise) predict a more emotional representation of the disease [25]. These elements must therefore be considered to build the relationship. On the other hand, in hypertension, a relationship that includes persuasion, which seeks to guarantee therapeutic compliance, may be important [19]. And a relationship of the type of mutual participation will be preferable when there are clear psychological and environmental factors: the doctor and patient will value the solutions to these psychosocial factors [26]. A trusting doctor-patient relationship shared decision-making support, full disclosure of side effects and cost sensitivity are attributes that might enhance primary adherence. Developing decision support interventions, that strengthen the doctor-patient relationship by enhancing doctor credibility and patient trust prior to prescribing, may provide more effective approaches for improving primary adherence [27]. In addition, it must be borne in mind that the deficient interrelation between doctor and family are very significantly associated with the lack of control of blood pressure. When the doctor-family relationship is good, control of blood pressure figures is more appropriate [28].

Doctor-patient relationship in asthma and COPD

In asthma and COPD there are important psychosocial factors, which suggests that the appropriate model of doctor-patient relationship is that of “mutual participation” in which will be possible to explore, ventilate and help the patient about their conflicts. But, often, information is not addressed, and the emotional burden of disease is underappreciated [29]. On the other hand, patient perceptions of financial burden and rates of cost-related nonadherence are high among individuals with asthma across the socioeconomic spectrum [30]. Patients most frequently report lack of communication surrounding issues relating to day-to-day management of asthma (30%) and home management of asthma (25%) [31]. Daily use of inhaled corticosteroids is the cornerstone of asthma treatment, although it is often suboptimal. The physician should consider the impact of positive and negative beliefs about inhaled corticosteroids on adherence in asthmatic patients. These beliefs are potentially modifiable and can help improve adherence and results, so they should be part of the communication and doctor-patient relationship [32]. In doctor-patient relationship, it must be taken into account that, approximately, 25% of patients with asthma prefer active role, 35% a collaborative role, and 40% to passive role. Only 33% of patients report that they received their most preferred role; 55% are less involved than they preferred. Patient related, professional related, and organizational factors (especially quality and duration of consultations), facilitate or hinder involvement. And role preferences are not associated with demographic variables or asthma severity [33].

Doctor-patient relationship in digestive system diseases

The most serious group of patients with functional digestive disorders (the most frequent being irritable bowel syndrome and non-ulcer dyspepsia) suffer more frequently from psychiatric illnesses and psychological dysfunctions (depression, anxiety, hypochondriasis, somatization, difficulties of interpersonal relationship, hostility, etc.). In these patients there is also a greater frequency of history of psychologically traumatic events, such as sexual or physical abuse, loss and unresolved duels. Therefore, there is a great importance of psychosocial factors in these pathologies. Social relationships, fatigue and other coexisting medical problems have a stronger effect on how patients with irritable bowel syndrome rate their overall health, than the severity of their gastrointestinal symptoms [34]. In these patients there is a greater concern for corporality, greater anxiety, apprehension and fears about the meaning of their symptoms. Interestingly, they tend to deny or minimize the influence of stress on their symptoms and the psychological problems that affect them. They are more likely to adopt the role of the sick, giving full responsibility for care to the doctor, without being able to make minimal therapeutic decisions. Generally, the digestive patient displaces feelings of dependence. They report their symptoms as of great intensity, in disproportion to the objective findings, and report greater social functional disability. From what has been said above, it seems evident that what stands out in this group of patients is a special attitude towards the disease. Consequently, it is of paramount importance in the treatment, to can establish a solid and effective doctorpatient relationship. The paternalistic model or the authoritarian model that can be effective in other situations is not in front of these patients. In these cases, it is best to appreciate that empathy (putting oneself in their place, understanding their motivations, fears and expectations) opens the doors to dialogue. It is not enough to verbalize it (“I understand perfectly how painful it has been for you ...”) but it is necessary to show it, since the patients, rather than by the phrase, perceive it by the gestures, the look, the posture. In these patients, the transference and counter-transference phenomena that appear in any therapeutic relationship arise with intensity; in such circumstances, overreacting must be avoided at all costs. It may be useful for the doctor to ask himself what this patient has that makes me feel that way. Only once a solid doctorpatient relationship has been achieved is it now possible to begin the process of re-education of the patient, to agree with him the most realistic expectations of the treatment, to make him more participative in the management of his illness and, above all, now it will be possible to investigate the traumas secrets guarded so jealously and finally propose psychological or psychiatric help [35].

Doctor-patient relationship in psychiatric diseases

The doctor-patient relationship is considered as a factor of great importance for the treatment of depression, where psychotherapy plays a significant role [36]. But often the relationship with these patients is feared and rejected by the doctor. Here there is usually a need to address emotions, feelings, and personal and sociofamily situations that are critical. These patients also often present accompanying or underlying very different somatic symptoms. This makes it necessary to fine tune sensitivity and maximize quiet listening skills. Further, in the relationship with these patients should be considered issues such as transference and countertransference, to consent and liabilities, confidentiality and patient protection [37].

For treating depression, a patient-centred model of practice helps to acquire necessary diagnostic information, but also to understand the patient’s subjective experience that presenting problems and the patient’s psychosocial context. That seems to be an important point to focus on in clinical practice, to improve the treatment of depressed patients. On the other hand, depressed patients with higher involvement in medical decisions have a higher probability of improving their symptoms. So, interventions to increase patient involvement in decision-making may be an important mean of improving care for and outcomes of depression. One of the goals clinicians may have is to achieve shared understanding between patient and themselves about the patient’s problems and their treatment [38].

Doctor-patient relationship in endocrinological diseases

The treatment is often chronic and requires hygienic-dietary changes, with detailed explanations at the cultural level of the pathophysiological mechanisms. The quality of the doctor-patient relationship has been shown to impact upon several health outcomes in diabetes, including psychological well-being. The association between doctor-patient relationship and diabetes-related distress is fully mediated by personal control, suggesting that the individuals’ beliefs surrounding their capacity to control their diabetes mediate the association between the doctor-patient relationship and disease-related distress [39]. Complex environmental, social, behavioural and emotional issues (known as psychosocial factors) influence the health of people living with diabetes, as well as their ability to manage it. The frustration, worry, anger, guilt, and burnout are caused by diabetes and its management (by glucose monitoring, medication dosing, and insulin titration) is known as diabetes distress. With a reported prevalence of 18% to 45%, this disease burden is quite common. Because high levels of diabetes distress are associated with low self-efficacy, poor glycaemic outcomes, and suboptimal exercise/dietary habits it is important to take it into account in the doctor-patient communications. Expression of fear, dread, or irrational thoughts, avoidant and/or repetitive behaviours, and social withdrawal are signs of anxiety that should prompt screening. It should be considered screening for anxiety in patients who express worry about diabetes, insulin injections or infusion, taking medications, and/or hypoglycaemia that interferes with self-management behaviours. Patients with diabetes should be screened for depression when medical status worsens; it is recommended to include caregivers and family members in this assessment. Patient-centred care is essential to promote optimal medical outcomes and psychological well-being in patients with diabetes. Doctor must be respectful and responsive to patient preferences, needs, and values; clinical decisions should be guided by patient values. If HbA1c is not at goal despite maximized medication therapy and lifestyle modification, it must be consider identifying and addressing any psychosocial factors that may be involved [40]. Empowerment perception, and diabetes distress are important determinants of HbA1c levels, so applying empowerment approaches such as enhancing self-awareness of improved glycemic control and sharing more decision-making power with insulin-treated patients with diabetes might have benefits for their glycemic control [41].

Doctor-patient relationship in hematological diseases

The diagnosis of a blood disease and its treatment raises many questions and concerns and entail multiple changes in the life of the patient and his family. This can affect the patient physically and psychologically, frequently appearing emotions and thoughts such as: fear of death, anger, hope, guilt, denial, sadness, envy, loneliness or anxiety. Another aspect to note is that after the treatments the patient feels abandoned and notices that they lack tools for their social integration (work, couple, sexual, family, friends, fertility, fatigue, etc.). A good doctor-patient relationship will facilitate the empowerment and the active role of the patient in the disease process. It should be provided to patients and their families the help and support they need. It is also important a subjective-individual protocol of the mental stability of the patient during cytotoxic chemotherapy. The success of the coping strategies to be developed is based not only on objective criteria, but also on the subjective evaluation mechanisms [19].

Doctor-patient relationship in cancer

Doctor must maintain a clear and permanent communication with the patient with cancer, offering the possibility of finding the space that may be denied in his personal area to express everything that concerns him. The doctor-patient relationship that is established will have a direct impact on the patient being able to openly express their fears and doubts, and to know in a real and objective way their illness and the possibilities of treatment [19,42]. Survivors of cancer often describe a sense of abandonment posttreatment, with heightened worry, uncertainty, fear of recurrence and limited understanding of what lies ahead [43]. Good-quality patient care extends beyond effective treatment to include good communication about therapeutic options, side effects, and the development of trust and confidence. Patients need access to accurate information, with providing information according to the patient’s profile, trying to provide patients with the information they are entitled to - the truth, although they often doctor can resort to the family assistance in providing that information, and an adequate length of the consultation. Providing effective and welltolerated treatments that minimise recurrence may help promote positive interactions [44,45].

Doctor-patient relationship in AIDS

A positive HIV antibody test or a diagnosis of AIDS changes many aspects of a person’s life, including the type of relationship they have with their doctor [17]. The main issues raised in this relationship are the knowledge of diagnosis and confidentiality (the diagnosis can be for the patient a reason for loss of work, family conflicts, derision and discrimination). The rights of these patients include non-discrimination, free circulation, access to technology and information, right to medical choice, dignified treatment, confidentiality and even death with dignity, among others. To be able to adapt more effectively to this relationship, doctors need to know how, each person, wants to be treated, particularly with regard to the degree and form of collaboration they wish to obtain during the treatment process. For example, taking pills every day is a permanent reminder of the presence of HIV. Revealing your condition is usually a problem: the patient may not be willing to initiate a treatment to be taken around the family or at work [46].

Doctor-patient relationship in rheumatic diseases

Two central themes for these patients are “being seen” and “being believed”. “Being seen” implies being an individual and not as a mere diagnosis, and “being believed” in regard to pain and suffering. These elements also imply being able to obtain a useful somatic diagnosis [47]. Therefore, these elements must be considered to establish the doctor-patient relationship in these patients.

Doctor-patient relationship in dermatological diseases

It has been shown that satisfaction in these patients depends on the diagnosis, but also on the ability of the doctor to provide explanations about the probable cause of the disease, information about how long the symptom will probably last and whether it shows empathy. Satisfaction also increases if the disease is serious but decreases if the doctor underestimates the quality of life related to the symptom [48-50]. These elements, therefore, should be considered in the relationship with patients with dermatological diseases.

Doctor-patient relationship in neurological diseases

In multiple sclerosis the patient must know his diagnosis, which implies being correctly informed by doctors from the beginning. Sometimes doctors avoid communication and only transmit the diagnosis to the patient if he asks directly. The patient and his family must be aware of each aspect of the disease in order to plan the future if necessary. Despite this, those affected continue to complain about the little information that is provided regarding the disease and the way it is administered. Regardless of the evolution and severity of the disease, the patient with multiple sclerosis always benefits with the help of a good doctor-patient relationship. It should be remembered that, with multiple sclerosis, not only the life of the patient is affected and modified, but also that of the family and the couple. The orientation to the patient about the new situation is a very difficult and important task, especially at the psychological level. They must be informed of the evolution of the disease, of the possibility of a benign evolution but also of a possible progression, being able to be led to a situation of remaining in a wheelchair, or else, of absolute dependence on the family. Patients must also be guided by the possibilities of medical treatment, rehabilitation and health care. It is very important in the doctor-patient relationship that the doctor knows to anticipate the possible emotional reactions after knowing the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. If the symptoms and signs of a first outbreak almost completely subside, the tendency of those affected is to consider the illness as a passing episode and not consider the personal or work future as a danger, and they do not give the value they should to the possible symptoms of disease. But these symptoms could alter the environment or work performance relationships. This attitude could be in principle is beneficial, since there may not be new outbreaks or progression of the disease for months or years, although careful monitoring is required [51,52].

In migraine, to improve doctor-patient communication in headache care, active listening and methods to gather information about deterioration, mood and quality of life related to headache should be included. [53]. In Parkinson’s disease patients experience a wide variety of negative emotions in the course of learning to cope with their illness. The fear and concern regarding its inevitable deterioration are expressed insistently by patients. Many of the patients are comforted by not being the only ones who have the disease, and most are kept afloat by faith that new scientific discoveries can one day lead to cure of the disease, while still alive. The quality of the adaptation to the disease depends to a large extent on the effectiveness of the treatment established, on the impact of the doctor’s style in dealing with the patient and on the speed of disease progression. The loss of motor control and the isolation of the world as the disease progresses become the most problematic facts of the disease, and generate a greater need for compensation through the help of the doctor, family, friends, associations or anyone else to be able to make patient feel a sense of belonging. Not all doctors can communicate adequately with Parkinson’s disease patients with the right words and feelings, but all patients with chronic disease must learn to adapt and endure the disease. However, there are patients with personality disorders or other psychiatric handicaps, particularly depression, who may reappear under the pressure of the disease and require special care. Patients with Parkinson’s disease have their own story to tell; It is vital for them to be able to share it with their doctor, as well as for their doctors to take it out. These stories ultimately speak of the daily courage and heroism of patients and families. All these stories confront the decline of good times and the increase of bad times throughout the day as the disease gradually dominates their lives [51]. Although basic research in dementia has grown significantly in recent years, care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease/dementia depends to a large extent on the doctor-patient relationship, families and social services. It is necessary to take care of the aspects that facilitate the coexistence of the family with the patient and with the social environment, recommending that the doctor-patient relationship be extended to the family in order to begin to assume the situation as soon as possible, as well as to seeking therapeutic treatment solutions, and avoid family frustration. Patient with Alzheimer’s disease must be treated with the respect and dignity that every human being deserves, according to their age, and helping them to participate and integrate as much as possible in the community. The abandonment of the patient to his luck accelerates the process of deterioration, while the insistence on learning new tasks, within the real capacity of the affected person, facilitates coexistence, the development of the patient in the middle and lightens the sensation of futility [51].

Conclusion

To improve communication and doctor-patient relationship according to the psychosocial aspects of the diseases, the doctor must listen carefully to the explanations of the patient to try to understand what he understands. Likewise, the doctor should explore the social and emotional context of the patient to understand the meanings of the determined disease. Thus, the contextualization or adaptation of the doctor-patient relationship according to different diseases has to do with “what is done”, with “how much is done”, and with “how it is done”.

References

- Turabian JL (1995) Notebooks of family and community medicine. an introduction to the principles of family medicine. Ediciones Díaz De Santos, Spain.

- Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE (1989) Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 27(3): 110-127.

- Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD (2002) Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract; 15(1): 25-38.

- Turabian JL, Pérez Franco B (2015) Observations, insights and anecdotes from the perspective of the physician, for a theory of the natural history of interpersonal continuity. Rev Clin Med Fam 8(2): 125-36.

- Ha JF, Longnecker N (2010) Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J Spring 10(1): 38-43.

- White P (2005) Biopsychosocial medicine. an integrated approach to understanding illness. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Polinski JM, Kesselheim AS, Frolkis JP, Wescott P, Allen CC, et al. (2014) A matter of trust: patient barriers to primary medication adherence. Health Educ Res 29(5): 755-763.

- Laws MB, Beach MC, Lee Y, Rogers WH, Saha S, et al. (2013) Provider-patient adherence dialogue in HIV care: results of a multisite study. AIDS Behav 17(1): 148-159.

- Turabian JL (2018) Doctor-patient relationship as dancing a dance. Journal of Family Medicine 1(2): 1-6.

- Rajaram U (2012) The patient-doctor relationship. Indian J Med Ethics 9(3): 156-157.

- Laín Entralgo P (2012) La relación médico-enfermo. Historia y teorí Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, Alicante, Spain.

- Turabian JL (2018) Doctor-patient relationship epidemiology and its implications on public health. Epidemol Int J 2(3): 000116.

- Turabián JL, Pérez Franco B (2010) The satisfaction adventures with the doctor-patient relationship in the land of questionnaires. Aten Primaria 42(4): 204-205.

- Eveleigh RM, Muskens E, Van Ravesteijn H, Van Dijk I, Van Rijswijk E, et al. (2012) An overview of 19 instruments assessing the doctor-patient relationship: different models or concepts are used. J Clin Epidemiol 65(1): 10-15.

- Ridd M, Shaw A, Lewis G, Salisbury C (2009) The patient-doctor relationship: a synthesis of the qualitative literature on patients' perspectives. Br J Gen Pract 59(561): 116-133.

- Turabian JL (2019) Doctor-patient relationships: a puzzle of fragmented knowledge. Family Medicine and Primary Care, USA.

- Herreman CR (1984) Medicina humaní Interamericana, México.

- Hopkins P (1972) Patient-centred medicine. Based on the first international conference of balint society in gran britain on “the doctor, his patient and the illness”. USA.

- González Menéndez R (1979) Psicología para médicos generales. Ciudad de La Habana, Editorial Científico-Técnica, Cuba.

- Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Nallamothu BK (2014) The hostile heart: anger as a trigger for acute cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J 35(21): 1359-1360.

- Parker GB, Cvejic E, Vollmer-Conna U, McCraw S, Smith IG, et al. (2018) Depression and poor outcome after an acute coronary event: Clarification of risk periods and mechanisms. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 53(2): 1001-1006.

- Pogosova N, Kotseva K, Bacquer DD, Von Känel R, Smedt DD, et al. (2017) Psychosocial risk factors in relation to other cardiovascular risk factors in coronary heart disease: results from the euroaspire IV survey. a registry from the european society of cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 24(13): 1371-1380.

- Turabián JL, Báez MB, Gutiérrez IE (2016) Type of presentation of coronary artery disease according the family life cycle. SM J Community Med 2(2): 1019.

- Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, Whalley B, Rees K, et al. (2017) Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 25(3): 247-59.

- Duwe EA, Holloway BM, Chin J, Morrow DG (2018) Illness experience and illness representation among older adults with hypertension. Health Educ J 77(4): 412-29.

- Ruiz Moral R, Rodríguez JJ, Epstein R (2003) What style of consultation with my patients should I adopt? practical reflections on the doctor-patient relationship. Aten Primaria 32(10): 594-602.

- Polinski JM, Kesselheim AS, Frolkis JP, Wescott P, Allen CC, et al. (2014) A matter of trust: patient barriers to primary medication adherence. Health Educ Res 29(5): 755-763.

- González Alfonso A, González Alfonso N, Vázquez González Y, González Alfonso L, Gómez Pacheco R (2004) Importancia de la participación familiar en el control de la hipertensión arterial. Medicentro 8(2).

- Partridge MR, Dal Negro RW, Olivieri D (2011) Understanding patients with asthma and COPD: Insights from a european study. Prim Care Respir J 20(3): 315-323.

- Patel MR, Wheeler JR (2014) Physician-patient communication on cost and affordability in asthma care. Who wants to talk about it and who is actually doing it. Ann Am Thorac Soc 11(10): 1538-1544.

- Newcomb PA, McGrath KW, Covington JK, Lazarus SC, Janson SL (2010) Barriers to patient-clinician collaboration in asthma management: the patient experience. J Asthma 47(2): 192-197.

- Ponieman D, Wisnivesky JP, Leventhal H, Musumeci-Szabó TJ, Halm EA (2009) Impact of positive and negative beliefs about inhaled corticosteroids on adherence in inner-city asthmatic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 103(1): 38-42.

- Caress AL, Beaver K, Luker K, Campbell M, Woodcock A (2005) Involvement in treatment decisions: what do adults with asthma want and what do they get? Results of a cross sectional survey. Thorax 60(3): 199-205.

- Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Thakur ER, Stewart TJ, Iacobucci GJ, et al. (2014) The impact of physical complaints, social environment, and psychological functioning on IBS patients’ health perceptions: looking beyond GI symptom severity. Am J Gastroenterol 109(2): 224-233.

- Renato Palma C (2002) The refractory patient with a functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. Rev méd Chile 130(2).

- Josué Díaz L, Torres LCV, Urrutia ZE, Moreno Puebla R, Font Darías I, et al. (2006) Factores psicosociales de la depresió Rev Cub Med Mil 35(3).

- Lakdawala PD (2015) Doctor-patient relationship in psychiatry. Mens Sana Monogr 13(1): 82-90.

- Llorca PM (2009) Severe depression: the doctor/patient relationship. Encephale 35(7): 310-313.

- Bridges HA, Smith MA (2016) Mediation by illness perceptions of the association between the doctor-patient relationship and diabetes-related distress. J Health Psychol 21(9): 1956-1965.

- Amy Butts, Billy St. John Collins, Joy Dugan (2018) What’s new in diabetes management: psychosocial care. Clinician Reviews 28(5): 10,12-13.

- Chen SY, Hsu HC, Wang RH, Lee YJ, Hsieh CH (2018) Glycemic control in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: empowerment perceptions and diabetes distress as important determinants. Biol Res Nurs 21(2): 182-189.

- Back A (2006) Patient-physician communication in oncology: what does the evidence show? Oncology (Williston Park) 20(1): 67-74.

- Parker PA, Banerjee SC, Matasar MJ, Bylund CL, Franco K, et al. (2016) Protocol for a cluster randomised trial of a communication skills intervention for physicians to facilitate survivorship transition in patients with lymphoma. BMJ Open 6(6): e011581.

- Lansdown M, Martin L, Fallowfield L (2008) Patient-physician interactions during early breast-cancer treatment: results from an international online survey. Curr Med Res Opin 24(7): 1891-1904.

- Santa Mariade APD, Serpade Araújo LZ (2011) Information to the patient with cancer: the oncologist's view. Rev Assoc Med Bras 57(2): 144-152.

- Anonymous (2011) Information, inspiration and advocacy for people with HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. Project Inform.

- Haugli L, Strand E, Finset A (2004) How do patients with rheumatic disease experience their relationship with their doctors? A qualitative study of experiences of stress and support in the doctor-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 52(2): 169-174.

- Magin PJ, Adams J, Heading GS, Pond CD (2009) Patients with skin disease and their relationships with their doctors: a qualitative study of patients with acne, psoriasis and eczema. Med J Aust 190(2): 62-64.

- Poot F (2009) Doctor-patient relations in dermatology: obligations and rights for a mutual satisfaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 23(11): 1233-1239.

- Taube KM (2016) Patient-doctor relationship in dermatology: from compliance to concordance. Acta Derm Venereol 96(217): 25-29.

- Duarte García-Luis J (2018) La relación médico-paciente en las enfermedades neurológicas, Spain.

- Yeandle D, Rieckmann P, Giovannoni G, Alexandri N, Langdon D (2018) Patient power revolution in multiple sclerosis: navigating the new frontier. Neurol Ther 7(2): 179-187.

- Buse DC, Lipton RB (2008) Facilitating communication with patients for improved migraine outcomes. Curr Pain Headache Rep 12(3): 230-236.

© 2019 Jose Luis Turabian. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)