- Submissions

Full Text

Associative Journal of Health Sciences

The Impact of Domestic Violence on Women’s Reproductive Health; The Analysis of Socio- Demographic Factors

Rosmala Nur*

Department of Public Health, Indonesia

*Corresponding author:Rosmala Nur, Department of Public Health, Indonesia

Submission: February 05, 2019;Published: February 20, 2019

ISSN:2690-9707 Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

Domestic violence is increasing every year. This study aims to determine the relationship between social demographic factors and reproductive health disorders due to violence. It is important to have early identification (screening) on groups that are vulnerable to the impact of violence. The study was conducted in Tinggede, Sunju and South Tinggede Villages, Sigi Regency, Central Sulawesi. There were 82 married women at childbearing age who had experienced violence as the sample of study. The data were collected using structured, in-depth interviews, moderate participation observation and documentation. In this study, the reproductive health disorders analyzed included complications of pregnancy and unwanted pregnancy. The results showed a difference between complications of pregnancy and non- complications of pregnancy in the aspects of age (X2=14,7; K=0,36), education (X2=7,0; K=0,26) and number of living children (X2=8,3; K=0,28). Age variable is most closely related to complications of pregnancy. Furthermore, the results of the analysis on the unwanted pregnancy and non-unwanted pregnancy groups showed that all the social demographic variables have differences. The social demographic factor that is most closely related to unwanted pregnancy is the education level variable with an X2 value of 20,5 and contingency coefficient (K) value of 0,42. Differentiation of reproductive health disorders (complications of pregnancy and unwanted pregnancy) related to the women’s social demographic conditions. The differences are related to their social demographic background regarding age, education level, and number of living children. Every woman has different social demographic characteristics so that the level of vulnerability to suffer the impact of violence is different for each individual.

<Keywords: Violence; Reproductive healths; Socio-demography

Introduction

In women’s reproductive health, the desired ideal condition is being free from pain and diseases, able to reproduce, and able to get healthy and safe birth [1,2]. Becoming a mother, women need support and affection from their husbands according to the purpose of marriage which is establishing a happy and prosperous family and supporting religious teachings in the form of the fulfillment of physical and conjugal needs and being a place to get love [3]. In contrast to this expectation, in fact, there has been an increase in the number of domestic violence to wives from year to year. Based on the data obtained from the Provincial Government of Central Sulawesi, in 2013, there were 49 domestic violence cases and in 2016 with 67 cases while in 2017, there were 92 domestic violence cases. This condition put Central Sulawesi Province in the 15th position out of 33 provinces in Indonesia. This number is estimated to be more undertest than that which appears [4]. Domestic violence committed by husbands to wives has some impact on reproductive health disorders. The impacts include complications of pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortion, premature birth/low birth weight babies, loss of sexual stimulation (frigidity) and the most fatal effects are maternal and neonatal deaths [5,6].

Some researchers have conducted some research on domestic violence and its impact on wives’ health, but no one has analyzed the difference of the impact. The analysis on demographic social factors and reproductive health was carried out to determine the social demographic characteristics of women who are vulnerable to the impact of violence. This is important to facilitate the identification (screening) on reproductive health disorders due to violence. Since this study found various types of reproductive health disorders, not all types of reproductive health disorders would be a unit of analysis because there were several conditions to consider in order to make a calculation using chi square. Based on the conditions, the reproductive health disorders analyzed in this study included complications of pregnancy and unwanted pregnancy.

Materials and Method

This study is an analytic observational study. It was conducted in the work area of Tinggede Community Health Center which included 3 villages, namely Sunju, Tinggede and South Tinggede Villages, in the period of February - June 2018. The population of the study was all pregnant women, postpartum mothers, and mothers with children under two years-old who had experienced violence from their husband. The sampling was conducted using total sampling method with 82 respondents.

Operational definition and objective criteria

1. Complications of pregnancy is a group of pregnant women experiencing and a group of pregnant women not experiencing not experiencing complications in pregnancy according to age, education level and number of Living Children.

The objective criteria are for the followings:

a. Age: ≤24 years old, 25-34 years old and ≥35 years old

b. Education level: ≤ elementary school, Senior High School, ≥Senior High School.

c. Number of Living Children: < 2 Children, 2-3 Children, ≥4 Children

2. Unwanted Pregnancy is a group of pregnant women experiencing and a group of pregnant women not experiencing Unwanted Pregnancy according to age, education level and number of Living Children. The objective criteria are for the followings:

a. Age: ≤ 24 years old, 25-34 years old and ≥ 35 years old

b. Education level: ≤ elementary school, Senior High School, ≥ Senior High School

c. Number of Living Children: < 2 Children, 2-3 Children, ≥ 4 Children.

Data collection and analysis techniques

The data collected in this study were in the form of primary data, collected through structured interviews, in-depth interviews, moderate participation observation and documentation. The data were analyzed using Chi Square Technique.

Result

Complications of pregnancy due to violence

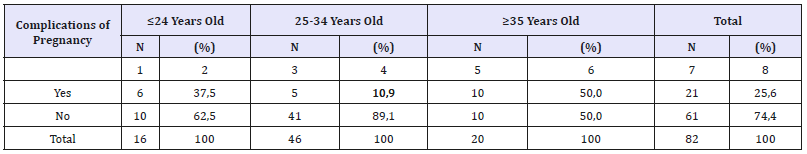

Age aspect: In Table 1, it can be seen that there are differences between the group with complications of pregnancy and the group without pregnancy complications according to the age of the respondents. In the group of women with complications of pregnancy, the old age group (≥35 years old) has a percentage of 50.0%, followed by the young age group (< 25 years old) with 42.3%. The percentages show that the group experiencing complications of pregnancy tends to be found in older and younger groups than in the group without complications of pregnancy. Although violence was experienced by respondents aged 25-34 years old, only 10.9% of those experienced complications of pregnancy and 89.1% did not experience complications of pregnancy.

Table 1:Complications of pregnancy due to violence based on age.

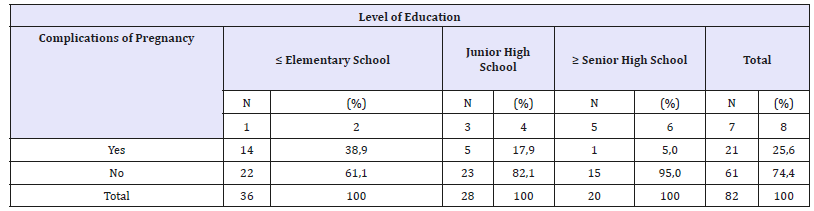

Education aspect: Table 2 shows that there are differences in complications of pregnancy based on the level of education of the wives. Complications of pregnancy mostly occur in the lower education group at 41.3% than those with high school (17.9%) and higher education (15.0%) levels. The highest percentage of the group without complications of pregnancy was found on wives with a level of education of ≥ Senior High School with 85.0% and the lowest was found on the level of education of ≤ Elementary School with 58.7%. The percentages show the tendency of the higher the education, the lower the incidence of complications of pregnancy.

Table 2:Complications of pregnancy due to violence based on level of education.

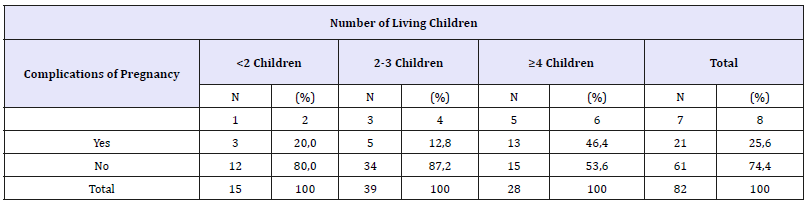

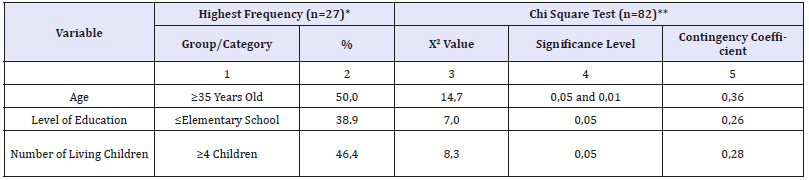

Living children (AMH) aspect: Wives who experience complications of pregnancy tend to have more living children (≥ 4 children) 46.4% compared to those who have or fewer children. Even though violence was mostly experienced by a group of wives who have 2-3 children, only 14,6% of those who had complications of pregnancy (Table 3). Table 4 shows that the highest complications of pregnancy with a total of 27 respondents occurred in the age group ≥35 years old (50,0%), lower education level (≤Elementary School) with 38.9% and ≥4 living children) with 46.6 % with an X2 value of 14.7; 7.0; 8.3 respectively.

Table 3:Complications of pregnancy due to violence based on number of living children.

Table 4:Description of socio-demography on respondents with complications of pregnancy based on the highest frequency and variable-based chi square test.

Unwanted pregnancy due to violence

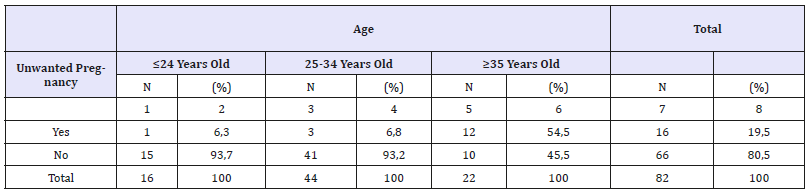

Age aspect: Unwanted pregnancy is mostly found in old age (≥35 years old) group with a percentage of 54.5% (Table 5). In the young age (≤24 years old) group, Unwanted pregnancy has a percentage of 6.3% and 6.8% in the 25-34 years old group.

Table 5:Unwanted pregnancy due to violence based on age group.

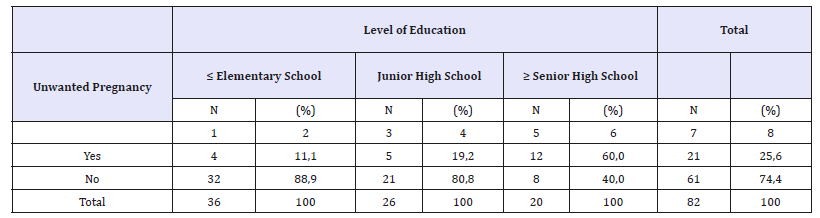

Education aspect: In Table 6, it can be seen that the number of those who experienced the highest unwanted pregnancy is that they with high school education (≥ Senior High School) with a percentage of 60.0%, compared to those with lower education (≤ Elementary School) with a percentage of 8,7%. This is compared to the number of those who did not experience the highest unwanted pregnancy, those with lower education (≤ Elementary School) with a percentage of 91.3%.

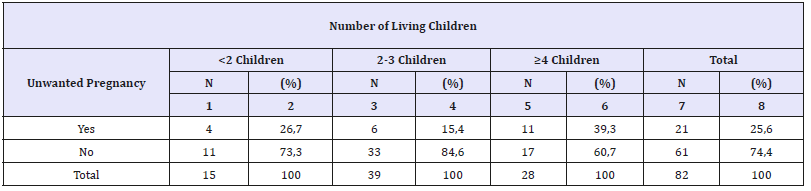

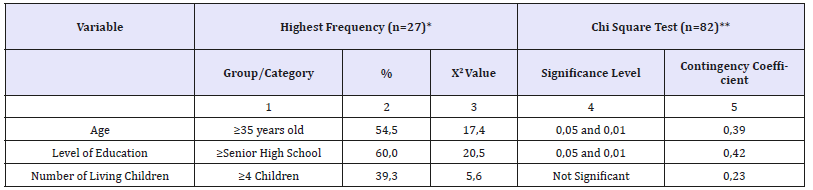

Living children (AMH) aspect: The distribution of the number of living children according to unwanted pregnancy showed from the results of this study in Table 7 is that the more the children a woman has, the higher the rate of unwanted pregnancy (≥ 4 living children with a percentage of 39.3%). Table 8 shows that the highest unwanted pregnancy with a total of 22 respondents occurred in the age group ≥35 years old (54.5%), higher education (≥Senior High School) level with 60.0% and ≥4 living children with 39.3% with an X2 value of 17.4; 20.5; 5.6, respectively.

Table 6:Unwanted pregnancy due to violence based on level of education.

Table 7:Unwanted pregnancy due to violence based on number of living children.

Table 8:Description of socio-demography on respondents with unwanted pregnancy based on the highest frequency and variable-based chi square test.

Discussion

Complications of pregnancy

Age aspect: After being tested with statistical test, with X2 value of 14.7 with significance level of 0.05 and 0.01, the age factor has significant differences between the age groups for complications of pregnancy. Women aged less than 20 years old or over 35 years old have a high risk of complications of pregnancy because of having lower haemoglobin levels, so the percentage of complications of pregnancy is higher [7]. The increasing age will experience changes in blood vessels and decreased hormonal function regulating the endometrial cycle [8]. In addition, it has the risk of essential hypertension and hypertension in pregnancy, diabetes mellitus and other chronic diseases as well as predisposing factors for placental abruption. So that even though they experience violence a little, the age of an elderly mother has the potential for placental abruption which causes bleeding (complications of pregnancy) [9]. Placental abruption can occur including a history of having experienced any violence towards the abdomen or experiencing domestic violence from the husband [10].

The low percentage of those who experience complications pregnancy at the age of 25-34 years old is closely related to the age of healthy reproductive maturity. A healthy and safe reproductive age is ranging between 20-35 years old. Pregnancy at the age of < 20 years old and >35 years old can cause complications, especially for the age of < 20 years old, because of immature and labile condition of pregnancy, both biologically, psychologically and economically [11]. Thus, both age groups are prone to complications of pregnancy. A little domestic violence from husband will result in the chance of getting complications of pregnancy. In contrast to the findings above, Jahanfar [12] found that women in Perak Malaysia who experienced domestic violence had no correlation between age and complications of pregnancy, but there was a correlation between the prevalence of violence and complications in pregnant women.

Level of education: The level of education of pregnant women has a great impact on how to behave in preserving health and understanding everything about the incidence of complications of pregnancy [13,14]. Therefore, the education factor has a great impact on a person’s thought, including knowledge, attitudes and actions in responding to complications such as causes of danger and prevention methods [15]. There is a tendency for complications of pregnancy to occur more frequently in groups of pregnant women with lower level of education. This is possible because they lack comprehension on the relationship between complications of pregnancy and other factors. In addition, women with lower level of education have less access to information about complications of pregnancy and its prevention.

Similarly, research [16] shows that education levels has an impact on the incidence of complications of pregnancy. Education factor can lead mothers to think critically and progressively in assessing their body and reproductive health, so that pregnancy care can be carried out more practically. Pregnant women with low education often underestimate or do not take the symptoms of bleeding and signs of other complications seriously [17]. Some mothers who experience violence still consider pregnancy not specially, so they do not need to pay too much attention to abnormalities, because of the limited knowledge [18]. Thus, women with lower level of education are prone to complications during their pregnancy.

Number of living children: After being tested with statistical test, with X2 value of 8.3 with significance level of 0,05, the distribution of the number of living children has significant differences according to the status of complications of pregnancy. This result is consistent with the analysis Survey of Demography and Health Indonesia 2017 [19] that high frequency of giving birth will be more at risk of experiencing complications compared to pregnant women who have a low frequency of giving birth. A mother will have the risk of complications when giving birth to more than four children compared to the frequency of giving birth between one and two children. This happens because it is possible for the mother to be not ready or recover physically and psychologically to get pregnant and give birth to the next child.

In contrast to Felly [8], in analysing the factors related to complications of pregnancy and of childbirth, it was found that there was no correlation between complications of pregnancy and parity. In other words, there is no difference in the number of living children between those who experience and who did not experience complications of pregnancy.

Description of socio-demography on complications of pregnancy: Age factor (≥35 years old) ranks highest in terms of socio-demographic factor that is related to complications of pregnancy due to violence with X2 value of 14.7 at the significance level of 0.01 and 0.05 with a contingency coefficient (K) of 0.36. This shows that age variable is the most closely related to complications of pregnancy. The greater the K value, the tighter the relationship between the two variables, where K value ranges from 0 and 1,00. Although those who experience violence occur in the 24-34 years old group, those who are prone to pregnancy complications tend to occur in the older age group (> 35 years old) because it is related to the age of healthy reproductive maturity [17,20]. Another thing that allows the high incidence of complications of pregnancy at the age of ≥35 years old is strongly related to prenatal care by professional health workers such as midwives, general practitioners and obstetricians [21]. The Survey of Demography and Health Indonesia 2017 [19] shows that the lowest frequency of pregnancy check-up for pregnant women occur in the ≥35 years old group with 90.1% and the highest one is found in the 20-34 years old group with 94.2%. The low frequency of getting pregnancy check-up can result in having no early detection of complications of. The age group should have higher frequency in pregnancy check-up because they are at high-risk age group [21,22].

Unwanted pregnancy due to violence

Age aspect: After being tested with statistical test, with X2 value of 17.4 with significance level of 0.05 and 0.01, the age factor has significant differences between the age groups and the incidence of unwanted pregnancy. This finding is quite relevant to the analysis the Survey of Demography and Health Indonesia 2017 [19], showing that unwanted pregnancy tended to increase in older age group. Age is an important variable in the analysis of unwanted pregnancy because age can be an indicator of the maturity of a woman biologically, especially for affecting fertility. The reproductive period generally occurs at the age of 15-49 years old [22,23]. However, it is now starting to be suspected that women have started reproductive periods earlier before 15 years old and ended after 49 years old because the level of health and nutrition of the community is getting better [12].

Women’s level of education: After being tested with statistical test, with X2 value of 20,5 at significance level of 0,05 and 0,01, the distribution of level of education of wives is significant according to unwanted pregnancy status. This is in accordance with the results of the Survey of Demograpy and Health Indonesia 2017 [19] that unwanted pregnancy increases linearly with the increase in the level of education. It means that the higher the education of a woman, the lower the percentage of getting the pregnancy wanted/ desired [7,24]. This symptom is easy to understand because high education will gain the knowledge, views and scope of a woman’s social interaction. Therefore, it will be easier to accept new ideas, including matters related to negotiations with their husband in the use of contraception. In addition, education will increase women’s awareness of the benefits of having fewer children [25]. Thus, women with high level of education tend to limit the number of children compared to those who are not educated or have lower level of education.

Number of living children: Although there is no difference between the number of living children and unwanted pregnancy, the results showed that the more the children a woman has, the higher the rate of unwanted pregnancy. Conversely, in the group of women who expect their pregnancy, the fewer the children a woman has, the greater the proportion of the wanted pregnancy. This indicates that the number of living children factor can have an impact on unwanted pregnancy, but the impact is not very visible because, as time goes by, many women with low parity do not want their pregnancy, even a newly married woman does not want to get pregnant yet, so they want to use contraception as a prevention to avoid pregnancy. The number of children is one of the important factors in determining the occurrence of unwanted pregnancy [26,27]. In general, unwanted pregnancy will be higher among couples who have more children than those who have fewer children. In other words, unwanted pregnancies will increase in proportion to the increasing number of children.

Description of socio-demography on unwanted pregnancy: The social demographic factor that is most closely related to unwanted pregnancy is the education level variable with an X2 value of 20,5 at a significance level of 0.01 and 0.05 with the contingency coefficient (K) is 0.42. Although the ≤ Elementary School group experienced a lot of violence, the highest impact of violence on unwanted pregnancy is in the ≥ Senior High School group. Unwanted pregnancy increases linearly with the increase in education level [28,29]. It means that the higher the level of education of women, the lower the percentage of women who want their pregnancy. This symptom is easy to understand because high education will gain the knowledge, views and scope of a woman’s social interaction. Therefore, it will be easier to accept new ideas, including matters related to negotiations with their husband in the use of contraception.

In addition, education will increase women’s awareness of the benefits of having fewer children. Thus, women with high level of education tend to limit the number of children compared to those who are not educated or have lower level of education. Data from Survey of Demograpy and Health Indonesia 2017 [19] showed the similar that the unwanted childbirth increases linearly with the increase of age and level of education. The high number of unwanted pregnancies causes a gap in the actual fertility rate with the desired fertility. Likewise, the national desirable fertility rate is only [1,2] but the total fertility rate is 2,4, so that it is reasonable when Survey of Demograpy and Health Indonesia,2017 [19] confirms that if the unwanted pregnancy can be prevented, then the total Indonesian fertility rate can be achieved. Thus, unwanted pregnancy has a significant contribution in achieving fertility rate in Indonesia [19].

Conclusion

Differentiation of reproductive health disorders (complications of pregnancy and unwanted pregnancy) is related to the women’s social demographic conditions. The differences are related to their social demographic background regarding age, education level, and number of living children. Every woman has different social demographic characteristics so that the level of vulnerability to suffer the impact of violence is different for each individual. The findings complete the theory of Heise [1] where Heise has never studied the differences in the impact on every woman. The differences are related to the soco-demographic background. Thus, the impact of domestic violence on women’s reproductive health cannot be explained significantly using the approach of Heise’s theory but it has to consider other factors such as women’s sociodemographic characteristics.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia for the research grant through 2018 National Grant Strategy program.

References

- Heise (2001) Reproductive health, gender, and human rights: A dialog. Women’s Reproductive Health Initiative (WRHI), PATH Washington, DC, USA.

- ICPD (1994) Paper international conference population deployment. Cairo, Egypt.

- Nurhajati L, Wardyaningrum D (2012) Family communication in marriage decision making at youth. J AL-AZHAR Indonesia Seri Pranata Sos 1(4).

- BPS (2016) Pending progress: analysis of data on childhood marriage in Indonesia. Badan Pus Stat.

- LH (1998) Violence against women, an integrated ecological framework. In: Stanley G, French, Wanda Teays dan Laura Purdy M (Eds.), Violence against women; philosophical perspective. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, USA, pp. 262-290.

- Nur R (2016) Impacts of violence during pregnancy-post childbirth to reproductive health of women at rural and urban areas. IJSBAR 21(2): 16-26.

- Akyüz A, Yavan T, Gönül Ş (2012) Aggression and violent behavior domestic violence and woman’s reproductive health: a review of the literature 17(6): 514-518.

- Felly P, Senewe (2001) Factors relates to the pregnancy complication and the last three years of childbirth in indonesia. Health of Research and deployment Republic Indonesia 32(2): 83-91.

- Samankasikorn W, Alhusen J, Yan G, Schminkey D, Bullock L (2018) Relationships of reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence to unintended pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 48(1): 50-58.

- Hakimi EN, Hayati, Marlinawati U, Anna Winkvist MCE (2001) Silent for harmony, violence to wife and women’s health in central java. LPKGM- UGM, Rifka Annisa WCC, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

- Fanslow J (2017) Intimate partner violence and women’s reproductive health. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 27(5): 148- 157.

- Jahanfar S, Kamarudin EB, Sarpin MA, Zakaria NB (2007) The prevalence of domestic violence against pregnant women in perak malaysia. Arch Iran Med 10(3): 376-378.

- Jewkes R, Africa S (2017) Sexual Violence (2nd edn).

- Rose SD (2013) Challenging global gender violence. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 82(3): 61-65.

- Mccarthy AS (2018) Intimate partner violence and family planning decisions: Experimental evidence from rural Tanzania. World Development 114: 156-174.

- Aarnio P, Kulmala T, Olsson P (2018) Husband’s role in handling pregnancy complications in mangochi district, malawi: A call for increased focus on community level male involvement. Sex Reprod Healthc 16: 61-66.

- Nur R, Mallongi A (2016) Research article impact of violence on health reproduction among wives in donggala. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 15: 980-988.

- Pallitto CC, Moreno GC, Jansen HAFM, Heise L (2013) Intimate partner violence, abortion , and unintended pregnancy: Results from the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. Int J Gynecol Obstet 120(1): 3-9.

- Statistik BP (2017) Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey (IDHS). Central Bureau of Statistics, Jakarta, Indonesia.

- Huang X, King C, Mcatee J (2018) Exposure to violence, neighborhood context, and health-related outcomes in low-income urban mothers. Health Place 54: 138-148.

- Nur KS dan R (2016) Assistance for pregnant mothers for students. Wahana Visi Indonesia, Indonesia.

- Alangea DO, Addo-lartey AA, Sikweyiya Y, Chirwa ED, Coker-Appiah D, et al. (2018) Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence among women in four districts of the central region of Ghana: Baseline findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 13(7): e0200874.

- Prihastuti D (2004) Advanced Analysis of SDKI 2002-2003. The Tendency of Fertility Preference, Unwanted Pregnancy in Indonesia. BKKBN, Jakarta, Indonesia.

- Khisbiyah Y (1997) Unwanted pregnancy on adolecentuth. Center for Population Studies UGM, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

- Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Splitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, et al. (1996) Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA 275(24): 1915-1920.

- Djoko Hartono HR dan EJ (1999) The Access of Health Service of Reproduction Health: Case Study in Jayawijaya Regency. Pulitbang Demograpghy and Work LIPI Collaborate to Australian National University (ANU-Canberra), Jakarta, Indonesia.

- Nur R (2016) Impacts of Violence during Pregnancy-post childbirth to reproductive health of women at rural and urban areas. Int J Sci Basic Appl Res 4531: 16-26.

- Hutagalung L, Manurita RR (2015) Socio-demography factors and socio- psychology that related to anemia of expectant mother in tanjung balai city, North Sumatra Province Health Department of North Sumatra, Medan, Indonesia.

- Nur R (2010) Violence in Post-Pregnancy and Its Impact on Women’s Reproductive Health in Donggala District. Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

© 2019 Rosmala Nur. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)