- Submissions

Full Text

Advancements in Case Studies

Orthorexia-Prevalence and Risk factors, Review of Literature

Izabela Łucka1* and Anna Łucka2

1Department of Developmental Psychiatry, Psychotic Disorders and Old Age Psychiatry, Medical University of Gdansk, Poland

2Faculty of Law and Administration, University of Gdansk, Poland

*Corresponding author:Izabela Łucka, Department of Developmental Psychiatry, Psychotic Disorders and Old Age Psychiatry, Medical University of Gdansk, Poland

Submission:August 14, 2023;Published: August 25, 2023

ISSN 2639-0531Volume4 Issue1

Abstract

Aim: The main aim of the study was to determine the prevalence and risk factors of orthorexia nervosa

based on a review of research papers published in PubMed, Wiley Online Library and Springer Link

databases.

Material and method: From the available studies, 56 articles were selected for final analysis, containing

research papers that used diagnostic questionnaires of orthorexia and analyzed potential risk factors for

its occurrence.

Results: According to research data from 3,1 to 41,7 %, on average, 20.6% of subjects were found to

be at risk of orthorexia nervosa, with the ORTO 15 questionnaire considering a score of 35 as the cutoff

point. The highest score of risk was observed in the group of subjects with eating disorders of the nature

of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, those who follow diets, those who are dissatisfied with the

appearance of their bodies, those who engage in intense physical exercise, those with maladaptive

personality traits, those who use immature defense mechanisms, and those who function poorly socially.

Additional risk factors appeared to be health-related studies-especially dietetics, occupational stress

(especially medics and musicians performing in orchestras).

Conclusion: It should be noted that in the ORTO 15 questionnaires, the cut-off point assumed by

the authors of the tool was 40 and its use significantly overestimated the results, so the researchers’

postulation to adopt a score of 35 in clinical practice, as indicating the risk of orthorexia, seems correct. In

research opinion for more effective diagnosis, it would be advisable to adopt a cut-off point for orthorexia

in the ORTO-15 at the level of 35 points, as postulated by some authors. The 40-point threshold is

associated with considerable overdiagnosis of the phenomenon. The analysis as a whole points to the

validity of placing ON in the eating disorder group, perhaps as a specific variant of anorexia nervosa. The

study showed no correlation of ON with OCD. Whilst this might suggest a substantial crossover between

symptoms of ON and eating pathology more generally.

Keywords:Orthorexia; Eating disorders; Prevalence; Risk factors

Introduction

In developed countries, including Poland, over the past decade or so, there has been a growing problem with unhealthy eating habits, with an increasing number of people suffering from both malnutrition and obesity. A relatively new phenomenon is Orthorexia nervosa (ON). This is a condition described as a pathological obsession with healthy eating,) first described by S. Bratman in 1997 [1]. The definition of the disorder currently proposed by Dunn and Bratman [2], indicates the need for the presence of medical symptoms secondary to dieting, resulting from malnutrition and weight loss and conflicts with others over dietary choices [2]. The above proposal is a recent attempt to frame ON from a diagnostic perspective since ON remains an entity with an unclear etiology, epidemiology, whose risk factors are variably identified and a nosological, non-determined status-Orthorexia, although clinically recognized, is not included in the ICD-11 (WHO 2022) and DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) classifications of diseases, customarily classified as other eating disorders. However, some researchers wonder whether the disorder is not a variant of obsessivecompulsive disorder and should be included in this diagnostic category.

In consideration of the above, the authors, on the basis of a review of the literature, using electronic access to medical databases MEDLINE/PubMed, Springer Link and Wiley Online Library, attempted to summarize previous observations contained in clinical studies conducted between 2006 and 2023. In the presented review, particular emphasis was placed on the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and the factors predisposing to its occurrence.

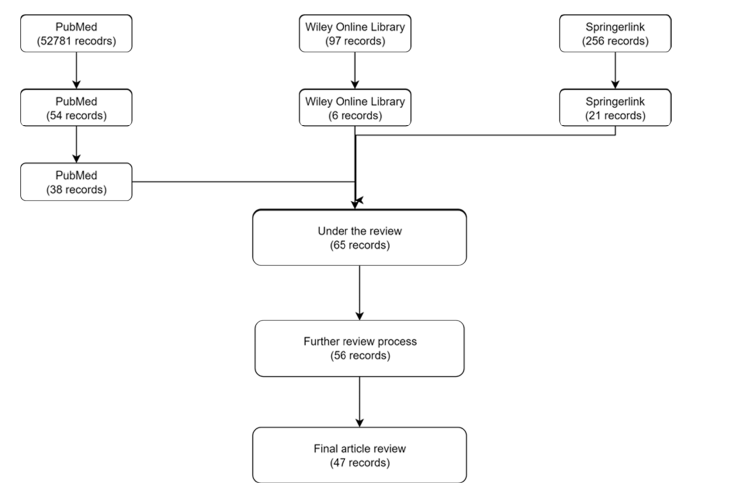

During the process of researching papers, the following keywords were used for the present analysis: “eating disorders “obtaining 52,781 records in the PubMed database, after narrowing the criteria with regard to the purpose of the study of eating disorders prevalence risk factors-54 records were found. Focusing on orthorexia-38 papers were extracted. From the Wiley Online Library database, 97 records were found including - 6 records on ON, prevalence, risk factors. From the Springer link database, 256 papers were found, of which 21 reports matched the purpose of the study and were extracted. Collective research studies were excluded and 56 articles published from 2006 to 2023, in English and Polish, were analyzed.

During the first phase, papers were selected on the basis of titles and preliminary evaluation of abstracts, while in the final phase the full texts of 56 research articles were analyzed and the exclusion criteria at this stage were methodological errors and studies that did not use questionnaires identifying orthorexia. The most commonly used questionnaires were the ORTO, BOT (Bratman Test for Orthorexia), Treuel Orthorexia Scale and Dusseldorf Orthorexia Scale. We excluded from further analysis studies that estimated the prevalence of behaviors focused on healthy eating in people who, for obvious reasons, should have such attitudes, e.g., nursing mothers in the postpartum period or people with somatic illnesses, e.g., gastroenterological problems. We also excluded studies that documented the beneficial health effects of mindfulness practices (lower risk of ON in this group). The final number of papers reviewed was 47. The selection process is illustrated by the diagram below (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Decision-making diagram.

Overview of the research review

The study included a group of 22230 people of both sexes. On the basis of a review of case reports, an attempt was made to estimate the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa and to isolate potential factors contributing to the development of this disorder. Said task is demanding due to the different groups analyzed, some of the papers deal with population studies, others deal with specific, selected groups, e.g.: people diagnosed with eating disorders, athletes, artists, presumably social media addicts (here the prevalence of orthorexia was estimated as high as 90.6%). It should be noted that different diagnostic questionnaires were used in the researched papers, which makes it significantly more challenging to obtain a potentially objective result. Additionally, in the ORTO-15 questionnaires, the cutoff point assumed by the authors of the tool was set to 40 and it was applied by some researchers which significantly overestimated their results; using said cutoff point, the prevalence of the phenomenon reached as high as 86% (range of results 56.4 - 86, 90.6%). Thus, the postulates of researchers who recognized these results as overestimates and rather advocated to adopt in clinical practice, using the ORTO-15 diagnostic questionnaires, a score of 35 as the cutoff point [3-6] seem correct. Given this approach, discarding of the extremely high scores and taking into account the other ORTO./BOT (Bratman Test for Orthorexia) questionnaires, the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa ranges from 6.5% to 41.7%, depending on the study, so it should be considered that an average of 24% of subjects were found to be at risk of orthorexia nervosa.

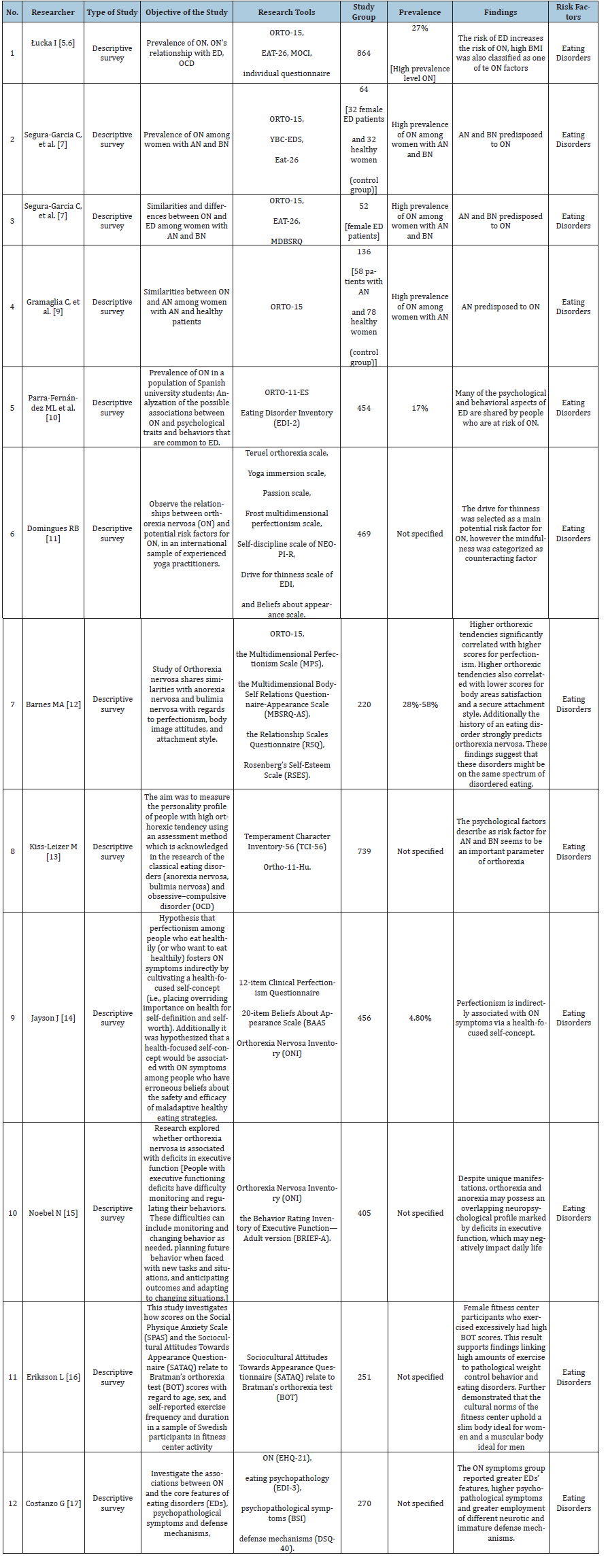

Researchers in twelve reports indicated that the highest score of risk was observed in the group of subjects with eating disorders of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa [5-16], (Table 1).

Table 1: Correlation of ON with eating disorders

Of particular relevance appear the studies on personality traits of people at risk of orthorexia, the most important of which are dissatisfaction with one’s body, striving for weight reduction, preoccupation with appearance and weight, difficulty adapting to new situations, use of immature defense mechanisms, low levels of self-compassion [13,15,17-21]. The aforementioned traits seem to be common to all individuals affected by eating disorders. An intriguing research finding is that both ON and ED sufferers have great difficulty identifying and regulating emotions but ON patients are able to describe emotions unlike those with other eating disorders [22]. The results of the analysis seem to confirm data emphasizing commonalities between ON and anorexia nervosa (AN). Orthorexia appears to be strongly associated with the symptoms observed in anorexia nervosa, particularly noteworthy are the tendency toward perfectionism, the tendency to over-exercise, the low level of social skills and the attitude toward nutrition, which is viewed as the primary means of feeling in control of oneself and one’s life [10,21,23-38]. Individuals with these disorders tend to also display abnormal attachment styles. Thus, it seems legitimate to classify orthorexia in the eating disorder division. We propose interpreting ON as a variant of eating disorders, as do most researchers who find many shared features in the examined individuals, both in the areas of personality, clinical symptoms and individuals’ functioning.

Studies analyzing the association between body mass index and the occurrence of orthorexia included a group of 5048 people, with two studies on 1312 people indicating a statistically significant association between high body mass index and orthorexia [6,39], a study on 1120 people found no association between BMI and orthorexia [40]. Three studies consisting of a group of 2,616 people indicated a statistically significant association between low BMI and orthorexia [23,41,42]. This observation seems interesting and warrants further analysis-perhaps the diagnostic tools are not precise enough, perhaps, like all screening tests, they isolate a risk group that includes both those who are affected and those who are just at risk of developing a full-blown disorder.

Additional risk factors for ON appeared to be health-related studies in the five studies conducted-particularly dietitians [40,42- 45]. Two reports pointed to occupational stress, particularly for medics and orchestra-playing musicians [46,47]. It seems worthy to consider the suggestion made by researchers. Pointing out the higher risk of orthorexia in those undertaking health-related studies, that their motivation (most likely unconscious) may be an attempt at self-medication through the knowledge they gain. Another intriguing thread for further observation is the implication of social-media influence on eating behavior; researchers have noted both positive and negative effects of content presented online on the prevalence of this phenomenon. Nevertheless-a significant association was found between the use of social media in excess and the risk of orthorexia [41,48-51]. The prevalence of orthorexia among those likely to be addicted to social media was estimated to be as high as 90.6% [48].

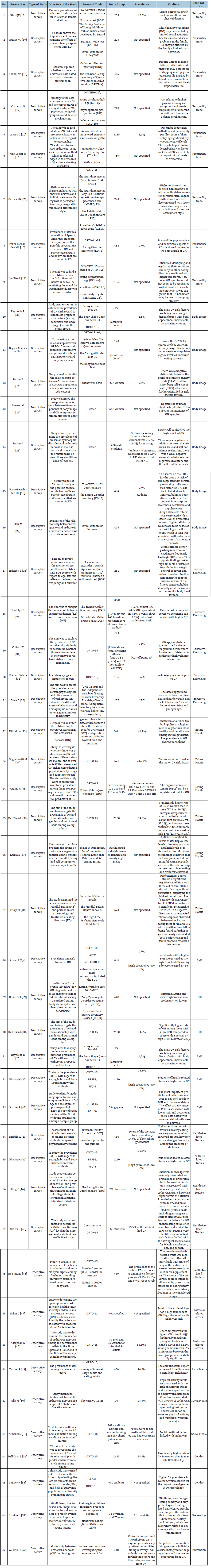

Observations on the correlation of the gender of the subjects with the risk of orthorexia-in two cases indicated the female gender as predisposing to the disorder. Other researchers have not observed this phenomenon [41,52]. Relevant in the consideration of the diagnostic classification of the disorder seem to be the observations of the authors of three studies involving 1254 people [5,17,24], who did not indicate an association of orthorexia nervosa with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Table 2).

Table 2:Additional risk factors.

Conclusion

In the studies analyzed, after rejecting extremely high scores, an average of 24% of subjects were found to be at risk of orthorexia nervosa. Applying the ORTO 15 orthorexia diagnostic questionnaires in clinical practice, a score of 35 should be taken as the cutoff point, otherwise the results artificially inflate the number of individuals considered as abnormal eaters, centered on a pathological fixation on healthy eating. It seems that it would be advisable to work on further refinement and standardization of the diagnostic tool that identifies orthorexia nervosa.

The main ON risk factors seem to be a correlation with ED as the highest score of risk was observed in the group of people with eating disorders, striving to achieve weight reduction, with perfectionist traits, following diets, dissatisfied with the appearance of their bodies, engaging in intense physical exercise, poor social functioning, with abnormal attachment patterns and abnormal personality traits, using immature defense mechanisms. Additional risk factors appeared to be health-related studies-especially dietetics and occupational stress. The relationship between gender and ON risk needs further observation. Further analysis of the influence of social media on the development of orthorexia nervosa also seems to be of interest. Apart from simply studying psychological and socio-cultural risk factors it may be of interest to study biological factors such as blood plasma, especially from these individuals for the development of orthorexia. As suggested in Martins’ studies [53-55], Sirtuin 1 may be linked to appetite control and focus on healthy diet & calorie restriction as well as over intense exercising, which all are to be considered major Orthorexia symptoms and risk factors. Furthermore, studies place Sirtuin 1 as a key protein needed for the proper brain function. It is believed that lack of activated Sirtuin 1 may be a risk factor for eating disorders and possibly orthorexia, thus plasma measurement of Sirtuin 1 may be of interest to the development of orthorexia and in overall eating disorders. A research paper by Strahler & all seems to summarize the role of well-being and mindfulness as major protective factors against eating disorders [56,57].

Funding Statement

Funding sources: No financial support was received for this study.

References

- Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C (2004) Orthorexia nervosa: A preliminary study with proposal for diagnosis and attempt to measure the dimension of the phenomenon. Eat Weight Disord 9(2): 151-157.

- Dunn TM, Bratman S (2016) On orthorexia nervosa: A review of literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav 21: 11-17.

- Stochel M, Janas-Kozik M, Zejda JE, Hyrnik J, Jelonek I, et al. (2015) Validation of the ORTO-15 questionnaire in a group of urban youth aged 15-21. Psychiatrist Pol 49(1): 119-134.

- Clifford T, Blyth C (2019) A pilot study comparing the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in regular students and those in university sports teams. Eat Weight Disord 24(3): 473-480.

- Łucka I, Janikowska-Hołoweńko D, Domarecki P, Plenikowska-Ślusarz T, Domarecka M (2019) Orthorexia nervosa-a separate clinical entity, a part of eating disorder spectrum or another manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder? Psychiatr Pol 53(2): 371-382.

- Łucka I, Janikowska HD, Domarecki P, Plenikowska ŚT, Domarecka M (2019) The prevalence and risk factors of orthorexia nervosa among school-age youth of Pomeranian and warmian-masurian voivodeships. Psychiatr Pol 53(2): 383-398.

- Segura-Garcia C, Ramacciotti C, Rania M, Aloi M, Caroleo M, et al. (2015) The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among eating disorder patients after treatment. Eat. Weight Disord 20(2): 161-166.

- Segura-Garzia C, Papaianni MC, Caglioti F, Procopio L, Nistico CG, et al. (2012) Orthorexia nervosa: A frequent eating disordered behavior in athletes. Eat Weight Disord 17(4): e226-233.

- Gramaglia C, Brytek-Matera A, Rogoza R, Zeppegno P (2017) Orthorexia and anorexia nervosa: Two distinct phenomena? A cross-cultural comparison of orthorexic behaviors in clinical and non-clinical samples. BMC Psychiatry 17(1): 75.

- Parra-Fernandez ML, Rodriguez-Cano T, Perez-Haro MJ, Onieva-Zafra MD, Fernandez-Martinez E, et al. (2018) Structural validation of ORTO-11-ES for diagnosis of orthorexia nervosa, Spanish version. Eat Weight Disord 23(6): 745-752.

- Domingues RB, Carmo C (2021) Orthorexia nervosa in yoga practitioners: Relationship with personality, attitudes about appearance, and yoga engagement. Eat Weight Disord 26(3): 789-795.

- Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML (2017) The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord 22(1): 177-184.

- Kiss-Leizer M, Rigó A (2019) People behind unhealthy obsession to healthy food: The personality profile of tendency to orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 24(1): 29-35.

- Jayson J, Nassim Tabri (2022) The association of perfectionism, health-focused self-concept and erroneous beliefs with orthorexia nervosa symptoms: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Eating Disorders 55(7): 892-901.

- Noebel NA, Oberle CD, Marcell HS (2022) Orthorexia nervosa and executive dysfunction: Symptomatology is related to difficulties with behavioural regulation. Eating and Weight Disorders 27(6): 2019-2026.

- Eriksson L, Baigi A, Marklund B, Lindgren EC (2008) Social physique anxiety and sociocultural attitudes toward appearance impact on orthorexia test in fitness participants. Scan J Med Sci Sports 18(3): 389-394.

- Costanzo G, Marchetti D, Manna G, Verrocchio MC, Falgares G (2022) The role of eating disorders features, psychopathology, and defence mechanisms in the comprehension of orthorexic tendencies. Eating and Weight Disorders 27(7): 2713-2724.

- Kinzl JF, Hauer K, Traweger C, Kiefer I (2006) Orthorexia nervosa in dieticians. Psychother Psychosom 75(6): 395-396.

- Mutluer G, Yilmaz D (2023) Relationship between healthy eating fixation (Orthorexia) and past family life and eating attitudes in young adults. American Journal of Health Education 54(2): 155-167.

- Lasson C, Raynal P (2021) Personality profiles in young adults with orthorexic eating behaviours. Eating and Weight Disorders 26(8): 2727-2736.

- Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML (2017) The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord 22(1): 177-184.

- Vuillier L, Robertson S, Greville-Harris M (2020) Orthorexic tendencies are linked with difficulties with emotion identification and regulation. J Eat Disor 8: 15.

- Reynolds R (2018) Is the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in an Australian university population 6.5%? Eat Weight Disord 23(4): 453-458.

- Brytek-Matera A, Fonte ML, Poggiogalle E, Donini LM, Hellas C (2017) Orthorexia nervosa: Relationship with obsessive-compulsive symptoms, disordered eating patterns and body uneasiness among Italian university students. Eat Weight Disorders 22(4): 609-617.

- Duran S, Çiçekoğlu P (2020) Relationship between orthorexia nervosa, muscle dysmorphic disorder (bigorexia), and self-confidence levels in male students. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 56(4): 878-884.

- Messer M, Liu C, McClure Z, Mode J, Tiffin C, et al. (2022) Negative body image components as risk factors for orthorexia nervosa: Prospective findings. Appetite 178: 106280.

- Sfeir M, Malaeb D, Obeid S, Hallit S (2022) Association between religiosity and orthorexia nervosa with the mediating role of self-esteem among a sample of the Lebanese population-short communication. Journal of Eating Disorders 10(1): 151.

- Eriksson L, Baigi A, Marklund B, Lindgren EC (2008) Social physique anxiety and sociocultural attitudes toward appearance impact on orthorexia test in fitness participants. Scan J Med Sci Sports 18(3): 389-394.

- Rudolph S (2018) The connection between exercise addiction and orthorexia nervosa in German fitness sports. Eat Weight Disord 23(5): 581-586.

- Clifford T, Blyth C (2019) A pilot study comparing the prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in regular students and those in University sports teams. Eat Weight Disord 24(3): 473-480.

- Valera JH, Acuña Ruiz P, Valdespino BR, Visioli F (2014) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among ashtanga yoga practitioners: A pilot study. Eat Weight Disord 19(4): 469-472.

- Bóna E, Szél Z, Kiss D, Gyarmathy VA (2019) An unhealthy health behaviour: Analysis of orthorexic tendencies among Hungarian gym attendees. Eat Weight Disord 24(1): 13-20.

- Dittfeld A, Gwizdek K, Jagielski P, Brzęk A, Ziora K (2017) Evaluation of the relationship between orthorexia and vegetarianism with use BOT (Bratman Test for Orthorexia). Psychiatr Pol 51(6):1133-1144.

- Guglielmetti M, Ferraro OE, Gorrasi ISR, Carraro E, Bo S, et al. (2022) Lifestyle-related risk factors of orthorexia can differ among the students of distinct university courses. Nutrients 14(5): 1111.

- Voglino G, Bert F, Parente B, Lo Moro G (2020) Orthorexia nervosa, a challenging evaluation: Analysis of a sample of customers from organic food stores. Psychology Health and Medicine 26(3): 1-9.

- Dell Osso L, Carpita B, Muti D, Cremone IM, Massimetti G, et al. (2018) Prevalence and characteristics of orthorexia nervosa in a sample of university students in Italy. Eat. Weight Disord 23(1): 55-65.

- Kalika E, Egan H, Mantzios M (2022) Exploring the role of mindful eating and self-compassion on eating behaviours and orthorexia in people following a vegan diet. Eat Weight Disord 27(7): 2641-2651.

- Miley M, Egan H, Wallis D, Mantzios M (2022) Orthorexia nervosa, mindful eating, and perfectionism: An exploratory investigation. Eat Weight Disord 27(7): 2869-2878.

- Bundros J, Clifford D, Silliman K, Neyman Morris M (2016) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among college students based on Bratman's test and associated tendencies. Appetite 101: 86-94.

- Plichta M, Jezewska-Zychowicz M, Gębski J (2019) Orthorexic tendency in Polish students: Exploring association with dietary patterns, body satisfaction and weight. Nutrients 11(1): 100.

- Dell’Osso L, Abelli M, Carpita B, Pini S, Castellini G, et al. (2016) Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationship with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 12: 1651-1660.

- Karniej P, Pérez J, Vela RJ, Arnedo IS, Caballero VG, et al. (2023) Orthorexia nervosa in gay men-the result of Spanish polish eating disorders study. BMC Public Health 23: 58.

- Dittfeld A, Gwizdek K, Koszowska A, Nowak J, Puzoń AB, et al. (2016) Assessing the risk of orthorexia in dietetic and physiotherapy students using the BOT (Bratman Test for Orthorexia). Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metabol 22(1): 6-14.

- King E, Wengreen H (2023) Associations between level of interest in nutrition, knowledge of nutrition, and prevalence of orthorexia traits among undergraduate students. Nutr Health 29(1): 149-155.

- Aktürk U, Gül E, Erci B (2019) The effect of orthorexia nervosa levels of nursing students and diet behaviors and socio-demographic characteristics. Ecol Food 58(4): 397-409.

- Bo S, Zoccali R, Ponzo V, Soldati L, Carli LD, et al. (2014) University courses, eating problems and muscle dysmorphia: Are there any associations? J Transl Med 12: 221.

- Erkin Ö, Kocaçal E (2022) Health perceptions and orthorexia nervosa tendencies among academics. Perspect Psychiatr Care 58(4): 2782-2790.

- Aksoydan E, Camci N (2009) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among Turkish performance artists. Eat Weight Disord 14(1): 33-37.

- Turner PG, Lefevre CE (2017) Instagram use is linked to increased symptoms of orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 22(2): 277-284.

- Villa M, Opawsky N, Manriquez S, Ananias N, Rodriguez ML, et al. (2022) Orthorexia nervosa risk and associated factors among Chilean nutrition students: A pilot study. J Eat Disord 10(1): 6.

- Yılmaze G (2021) Orthorexia tendency and social media addiction among candidate doctors and nurses. Perspect Psychiatr Care 57(4): 1846-1852.

- Valente M, Renckens S, Aelen JB, Syurina EV (2022) The #orthorexia community on Instagram. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 27: 473-482.

- Sanlier N, Yassibas E, Bilici S, Sahin G, Celik B (2016) Does the rise in eating disorders lead to increasing risk of orthorexia nervosa? Correlations with gender, education, and body mass index. Ecol Food Nutr 55(3): 266-278.

- Martins IJ (2017) Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. J Clin Epigenet 3(3): 24.

- Martins IJ (2016) Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research 5(1): 9-26.

- Martins IJ (2018) Sirtuin 1, a diagnostic protein marker and its relevance to chronic disease and therapeutic drug interventions. EC Pharmacology and Toxicology 6(4): 209-215.

- Strahler J, Hermann A, Walter B, Stark R (2018) Orthorexia nervosa: A behavioral complex or a psychological condition? J Behav Addict 7(4): 1143-1156.

© 2023 Izabela Łucka. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)