- Submissions

Full Text

Advancements in Case Studies

A Case of Frontal Meningioma Presenting as Frontal Lobe Syndrome

De Moura N1*‡, Margarida Fraga2‡, Facucho-Oliveira J2‡, Esteves-Sousa D2, Canas- Simião H1 and Ilda Costa3

1Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Western Lisbon Hospital Center, Portugal

2Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Cascais Hospital, Portugal

3Department of Neurology, Portuguese Institute of Oncology in Lisbon, Portugal

‡These authors contributed equally to the present manuscript

*Corresponding author: Nuno Moura, Western Lisbon Hospital Center, Portugal

Submission:October 18, 2021;Published: November 18, 2021

ISSN 2639-0531Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

Frontal lobe syndrome (FLS) is a wide designation used to describe the impairment of some of the higher functions of the brain such as motivation, executive functions, emotional regulation, and language or speech production. We present the case of a 59-year-old diagnosed with a large frontal lobe meningioma showing clinical signs and symptoms of frontal lobe dysfunction both before and after the tumor excision. Despite being quite common, most frontal meningiomas are asymptomatic and grow very slowly. Patients with such tumors are often referred first to psychiatrists because they may present with symptoms resembling depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. Symptoms like headache and recent memory loss should make the clinician aware of frontal meningioma as a possible cause and hence a neuroradiological investigation should be considered.

Keywords: Meningioma; Frontal lobe syndrome; Neuropsychiatric symptoms

Abbreviations: FLS: Frontal Lobe Syndrome

Introduction

FLS is a clinical entity described since ancient times, essentially in the context of head

trauma. The earliest known accounts are from Edwin Smith Papyrus, about 5000 years

ago which contained the first 27 head injury records [1]. It was not until the 17th century

that Thomas Willis attributed higher cognitive functions to the cerebral cortex. Gall and

Spurzheimer’s phrenological studies in the nineteenth century, subsequently, argued that

since animals have smaller frontal lobes compared to humans, this area had to harbor the

highest human functions bringing the first functional attributions to the frontal lobes, namely

speech and calculus [2]. During this period, Broca and Wernicke also described several cases

of aphasia related to left frontal lobe lesions [3].

Despite subsequent studies by Kleist, Goldstein and others, the case of Phineas Gage,

described by John Harlow in 1848 became the most famous and paradigmatic description

of what is known today as FLS. Gage suffered a bilateral frontal injury, particularly the

orbitofrontal and anterior medial regions, secondary to head trauma enabling a major step

in understanding the frontal lobe function by description of a wide range of character and

behavioral changes he presented.

Since then, the concept of FLS has been used to describe a wide

range of changes due to an injury to the frontal region, including

severe deviations in the patterns of social interaction, personality,

personal memories and self-criticism, without the same degree of

apparent damage in other brain functions [4]. The etiology ranges

from head trauma, tumors, infections, neurodegenerative diseases

to the much more common cerebrovascular disease. Damage to the

frontal lobes can have widely varying behavioral consequences,

depending upon the location, extent, and etiology of the lesion or

degeneration.

Ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex

Lesions in this region are associated with the commonly described “frontal lobe personality”. Patient’s behavior may change drastically bringing about emotional instability, marked impulsivity, and impaired social cognition. This type of clinical findings is often related to lesions in Brodmann’s Areas 10, 11, 12, and 47. Many studies have emphasized inflexibility, impulsiveness, and emotional disturbances following Orbitofrontal cortex damage in humans and monkeys [5].

Dorsolateral and anterior cingulate cortex

Injuries to the dorsolateral region are known to affect working memory, planning and prioritizing, task initiation and attention [6]. Symptoms like abulia, avolition, laconic speech may accompany dorsolateral frontal as well as anterior cingulate cortex lesions and might be wrongly interpreted as being part of a psychiatric disorder.

Case Presentation

The subject is a 59-year-old man with an unremarkable medical and psychiatric history. Two months prior to the diagnosis, he began presenting mild headache unresponsive to ibuprofen, marked irritability, neglect of hygiene in association with domestic squalor and disorganized behavior with periods of apathy interspersed with verbal and physical aggression. During that time, he also experienced episodes of urinary incontinence, abnormal gait and gross memory lapses. He went to a family practice consultation and two months later a cranial CT scan was performed showing an extra-axial expansile lesion in the left frontal region. He was, then, brought to the emergency department and transferred to the neurosurgery inpatient unit for further diagnostic evaluation and surgical intervention.

Laboratory studies: Blood Count: normal; blood chemistry: normal; liver function: normal; thyroid Function: normal; lipids: normal; serum electrolytes: normal.

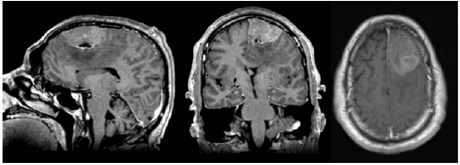

Image study: Cranial MRI showed a left parasagittal frontal lesion compatible with a meningioma (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Brain MRI at admission showing a large mass involving the left frontal region, suggestive of a giant meningioma.

Treatment

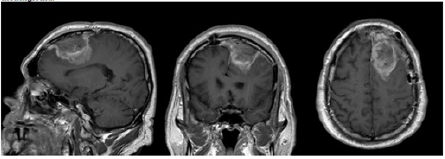

The patient underwent a bilateral frontal craniotomy for tumor excision with no surgical intercurrences (Figure 2). The neuropathology report confirmed the tumor’s total resection as well as the diagnosis of an atypical meningioma (Grade II, WHO). He was started on sodium valproate 500mg t.i.d. and given regular neurology and neurosurgery outpatient consultations after discharge. During the following year the patient was also submitted to external radiotherapy (3D-CRT) on the tumor bed, with 15Mv and 6Mv photons using 3 fields with a fractionation dose of 2Gy in a total of 30 fractions without intercurrences.

Figure 2: Brain MRI image the day after surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

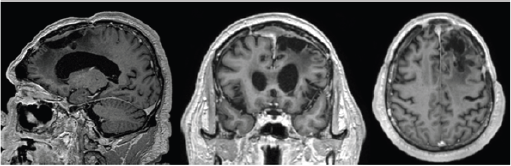

During the two-year follow-up there were no MR imaging signs of tumor recurrence (Figure 3) and the patient remained seizurefree taking levetiracetam 1000mg b.i.d. Neurological examination has remained normal excluding the cognitive functions. In that regard, the patient continues showing difficulty in planning tasks and lacking conceptual thinking. His speech remains slurred and repetitive and according to the family he remains apathetic and dependent being incapable of performing activities of daily living. The neuropsychological report, two years after surgery, correlates with the clinical findings showing an impairment across multiple domains, including verbal and logic memory and associative learning skills and executive functions.

Figure 3: Brain MRI two years after surgery.

Discussion

Meningiomas are the most common benign brain tumors, accounting for 13%–26% of intracranial tumors [7] being more frequent in females and adults aged 65 and older. Most of them do not cause symptoms till late, grow slowly and frontal lobe meningiomas are particularly “silent”, and therefore likely to be misdiagnosed or overlooked. Patients’ clinical symptoms can easily be mistaken with a psychiatric disorder like depression and, in some cases schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, delaying proper treatment, and exposing the patient to unnecessary side effects. Psychiatric symptoms may be the only initial manifestations of meningiomas of the brain in a significant number of cases (21%) occurring in the fifth decade of life. Headache, papilledema, and focal neurological signs may develop only when the tumor has reached an advanced stage [8]. No previous history of psychiatric disorder, the onset of symptoms after 35 years of age and an insidious and progressive psychological change increase the likelihood of a diagnosis of frontal lobe syndrome [9]. In the reported case, the patient also presented with headache, urinary incontinence and abnormal gait which would point to an “organic” brain syndrome and consequently the most adequate treatment.

Conclusion

FLS is a heterogeneous clinical entity of great relevance for its enormous contribution to neuropsychology and frontal lobe neuroanatomy. The etiology is diverse including potential curable causes like infections and tumors and others that may only be manageable like neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular diseases. Frontal meningiomas are an uncommon cause of FLS and may present a challenge given the slow growth, the paucity of the symptoms in the early stages and frequently mimicking a psychiatric disorder. While it is not practical to subject every patient presenting with psychological symptoms to a neuroradiological exam, features like the onset of symptoms after 35 years of age and no previous psychiatric history, headache, slowly progressive psychological change and neurologic deficits may justify screening with cranial CT or MRI.

References

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P (2017) Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry.

- Estévez-González A, García-Sánchez C, Barraquer-Bordas L (2000) The frontal lobes: the executive brain. Rev Neurol 31 (6): 566-577.

- Mendoza JE, Foundas AL (2008) Clinical neuroanatomy: A neurobehavioral approach. Clinical Neuroanatomy: A Neurobehavioral Approach, pp. 1-704.

- Stuss DT, Picton TW, Alexander MP (2001) Consciousness, self-awareness, and the frontal lobes. In: The frontal lobes and neuropsychiatric illness. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. USA, pp. 101-109.

- Szczepanski SM, Knight RT (2014) Insights into human behavior from lesions to the prefrontal cortex. Neuron 83(5): 1002-1018.

- Barbey AK, Koenigs M, Grafman J (2013) Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory. Cortex 49(5): 1195-1205.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, Collie D (2004) Meningiomas. Lancet 363(9420): 1535-1543.

- Yakhmi S, Sidhu BS, Kaur J, Kaur A (2015) Diagnosis of frontal meningioma presenting with psychiatric symptoms. Indian J Psychiatry 57(1): 91-93.

- Mumoli N, Pulerà F, Vitale J, Camaiti A (2013) Frontal lobe syndrome caused by a giant meningioma presenting as depression and bipolar disorder. Singapore Med J 54(8):158-159.

© 2021 De Moura N. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)