- Submissions

Full Text

Advancements in Case Studies

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Following Dabrafenib and Trametinib for Stage 3c Locally Advanced Inoperable Melanoma: A Case Report

Julia Fullerton, Hywel Cooper and Chit Cheng Yeoh*

Dept of Oncology, Portsmouth Hospitals University Trust, Queen Alexandra Hospital, UK

*Corresponding author: Chit Cheng Yeoh, Dept of Oncology, Portsmouth Hospitals University Trust, Queen Alexandra Hospital, UK

Submission:April 15, 2021;Published: May 17, 2021

ISSN 2639-0531Volume3 Issue1

Abstract

Severe cutaneous manifestations are commonly seen in drug hypersensitivity reactions which can present as pustular and bullous skin eruption. This can further progress and deteriorate into Steven- Johnsons syndrome or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis syndrome (TENs) which require hospitalization. We report the case of a woman in her early fifties with metastatic melanoma who developed SJS and TENs 11 days following administration of Dabrafenib and Trametinib. Interestingly our patient had previously undergone 4 cycles of dual immunotherapy followed by single infusion of Nivolumab prior to this. Nivolumab had to be stopped due to grade 3 toxicity (hepatitis and hypoadrenalism). We believe this primed her immune system for potentially any hypersensitive reaction, in addition to attacking cancerous cells. Dabrafenib and Trametinib was commenced 18 days after discontinuation of immunotherapy. Our patient developed symptoms consistent with SJS and TEN, which was later confirmed on skin biopsy. She recovered well and following ITU admission and step down to oncology inpatient ward was discharged home. To our knowledge there are no links between Dabrafenib and SJS and TEN, although this has been reported in other BRAF inhibitors such as Vemurafenib. We changed her treatment to a third type of BRAF inhibitor, Encorafenib and Binimetinib (MEKtovi) which resulted in good Complete response control of her Melanoma for 6 months, to date.

Keywords: Skin side effects with Melanoma treatment; Dabrafenib and trametinib; Steven-Johnsons Syndrome (SJS); Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis syndrome (TENs); Encorafenib and binimetinib; Vemurafenib; Complete response; Prior immunotherapy before BRAF inhibitors

Abbreviations: TEN: Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis; SJS: Steven-Johnsons Syndrome; (BRAF/MEKi): BRAF and MEK inhibitor biologic tablets

Introduction

Severe cutaneous manifestations are commonly seen in drug hypersensitivity reactions these can further progress and deteriorate into generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Steven-Johnsons syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) which are classified as emergencies and require hospitalisation1. Whilst drugs such as allopurinol, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, nevirapine, oxicam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, sulfamethocazole and other sulpha antibiotics are known to be high risk for causing SJS and TEN [1], there is little data available describing a direct link of dabrafenib (BRAF kinase inhibitor) and trametinib (selective reversible allosteric MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor) and SJS or TEN. This case reports explore meta-analysis of the reported cases skin side effects of BRAF inhibitors and the mechanisms which may cause it. We explore too the contribution of prior immunotherapy may have made to this adverse skin side effects. Here we see a complete response to melanoma while on the biologic’s tablets.

Case Report

Our case describes a female patient in her early fifties with locally advanced inoperable right pinna and pre-auricular melanoma with associated lymph nodes. She has moderate volume measurable pigmented disease, which recurred very soon after surgery with a nonhealing pigmented wound (Figure 1). At the beginning of the 2020 the patient underwent a right total conservative parotidectomy, complete pinnectomy, right neck dissection followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab with curative intent but after one month presented in clinic with new neck lumps. PETCT confirmed local right neck nodes and pre-auricular recurrence. She was switched to palliative doublet immunotherapy with Nivolumab & Ipilimumab in June. Unfortunately, our patient suffered side effects, developing grade 3 hepatitis and hypoadrenalism (G3) as well as thyroid dysfunction (G2). The decision was made to switch to Nivolumab only and start Dabrafenib and Trametinib at the beginning of September 2020.

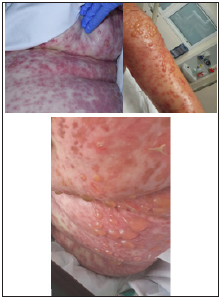

At the time of starting Dabrafenib and Trametinib the hepatitis had resolved, and endocrine issues were well controlled with hydrocortisone and levothyroxine. Further surgery had been considered prior to starting Dabrafenib and Trametinib but unfortunately her melanoma had started to fungate (Figure 2). Eleven days after starting Dabrafenib and Trametinib the paramedics were called out to see the patient at home. They reported swollen lips, extreme vomiting, shortness of breath and temperature of 40 degrees Celsius. The patient was brought to A&E for possible anaphylaxis. The patient was stabilised in A&E and reviewed by Dermatology. At this time the patient had a widespread maculopapular rash across her body, vesicular eruptions over the right side of face, neck, chin, shoulders, as well as oedema over her lips, tongue, ears, face and neck. She was Nicholsky sign positive with evidence of desquamation (Figure 3). A diagnosis of Toxic epidermal necrolysis was made, and the patient was transferred to ITU for pain management, tight fluid balance and intensive wound management. Whilst on ITU she did not require any inotropic support or ventilatory support. She was treated for suspected sepsis with multiple antibiotics which were later rationalised to vancomycin alone. The patient was able to be stepped down to an oncology ward and stayed 2 weeks for need of intravenous hydration and regular specialist nursing application of her topical creams and balms (Figure 4) and later discharged home.

Figure 1: Early starting of progression of Melanoma, as seen with painful scar, and pigmented scar. Neck tension is stiff, and early signs of primary preauricular lump returning.

Figure 2: Fungating neck cervical lymph node, and pre-auricular primary Melanoma recurrence as seen as purple hue mass in front of ear. Cotton wool bud in ear to help with the discharge from growing mass lesion. Pain in ear needing strong analgesia.

Figure 3: Toxic epidermal necrolysis, day of admission to Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Rash on left abdomen at initial presentation, and bullous on day 2, and day 3. Systemic shock, needing fluid resuscitation, and urgent skin biopsy, and review as dermatology emergency. Fortunately, no inotrope infusion required in 2 day stay in ICU.

Figure 4: As she recovered and came out of Intensive Care Unit, patient had 2 weeks in hospital for skin care by Dermatology as in patient, with creams (5 times a day application) and IV hydrations. The systemic steroid injections weakened her proximal muscle, and physiotherapy service was given to strengthen her core muscles.

IGNg ELISpot and lymphocyte proliferation testing was done by the Dermatology Team. They concluded that whilst there were no positive signals for any drugs tested in either assay, the patient had been exposed to significant amount of steroid at the time of testing and check-point inhibitors e.g. pembrolizumab and nivolumab, cause TEN-like eruptions via different mechanisms than direct T cell-drug/MHC recognition, therefore the causative agent in our patient is most likely to be a check-point inhibitor. The incisional skin biopsy from left arm on microscopic examination showed sections of skin with subepidermal bulla formation with overlying partial and full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis (Figure 5). At the edge of the blister cavity there are occasional single necrotic keratinocytes. Parts of the blister should re-epithelialisation. The papillary dermis showed oedema with occasional junctional clefting, and mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate. There was no evidence of granuloma formations, vasculitis or panniculitis. PAS staining was negative for fungal organisms. The histopathologists concluded the overall appearances were most compatible with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Figure 5: Toxic epidermal necrolysis, Skin biopsy section showing a sub epidermal bulla with epidermal necrosis and mixed inflammatory infiltrates, Haematoxylin and Eosin stain (magnification x 20).

Discussion

Global medical information was sought and according to EU risk

management plan, there have been no case of SJS or TEN reported

with dabrafenib treatment. However, it is well documented in the

literature that the BRAF inhibitor Vemurafenib can cause severe

cutaneous reactions, including SJS. Skin biopsy on our patient

showed subepidermal bulla formation with overlying partial and

full thickness necrosis of the epidermis. At the edge of the blister

cavity there are occasional single necrotic keratinocytes. The

papillary dermis shows oedema with occasional junctional clefting,

and mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Overall appearances are

most compatible with toxic epidermal necrolysis. IFNg ELISpot test

was requested on these drugs following Mrs DH case. Dabrafenib,

trametinib, Omeprazole, Encorafenib, Vemurafenib, Binimetinib

with positive and negative control. ELISPOT Assay is used to

measure peptide specific IFN-gamma production which is crucial

against intracellular pathogens and for tumour control. Lymphocyte

proliferation is also looked at on each of these drugs.

There were no positive signals for any of the drugs tested in

either of the assays. With these caveats-the test does not exclude

hypersensitivity but makes the probability of them as causal less

likely for TENS. However, the sensitivity of this test could be reduced

as patient has been desensitize with steroid and antihistamine prior

to this test been done. Melanomas are aggressive skin cancers with

a median survival of between six and nine months in patients with

metastatic disease prior to introduction of immunotherapies and

newer small molecules. Debrafenib and trematenib are selective

BRAF and MEK inhibitors that have been shown to improve the

survival of patients with BRAF‐mutated metastatic melanomas.

They are administered until disease progression or unacceptable

toxicity occurs [2]. This mutation has been identified in over 50

percent of malignant melanomas [3]. The patient in this case was

taking omeprazole, Debrafenab and trematinib at the time of

developing Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).

Grade I-II cutaneous adverse events (such as photosensitivity,

itching and rash) are commonly seen with BRAF inhibitor use

(up to 64% of the patients), but severe reactions to therapy such

as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/

TEN) are uncommon. Vemurafenib-induced severe cutaneous

adverse reactions (SCARS) and SJS/TEN are more common;

desensitization and treatment with a lower dose of vemurafenib

and switching to an alternate BRAF inhibitor have been used

to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. Interestingly, cutaneous

adverse events are less common with BRAF/MEKi combinations

such as Dabrafenib-Trametinib, Encorafenib-Binimetinib or even

Vemurafenib-Cobimetinib when compared to vemurafenib alone.

There is however a high frequency of occurrence of targeted

therapy SCARs in previously immunotherapy-treated patients

(45.2% of the patients) [4,5]. The patient in this case has had

previous immunotherapy prior to Debrafenib-Trametinib therapy.

The mechanisms of this immune related dermatologic adverse

events (irAE) are not fully understood. However, it is clearly related

to T cell activation mediated by inhibiting the PD‐1/PD‐L1 and

CTLA‐4 pathway. As the PD‐1 blockade augments T‐helper cell

1(Th1)/Th17 signaling pathway it could promote pro-inflammatory

cytokines mediated by Th17 lymphocytes [5]. Patients who

develop TEN while on BRAF/MEKi will benefit from high dose

steroids and possibly intravenous immunoglobulins though this

data is controversial. In severe cases or steroid unresponsive

cases systemic treatments with ciclosporin or anti-TNF therapies

may be considered [5]. After full recovery an alternative BRAF/

MEKi may be considered if appropriate. Since BRAF/MEKi therapy

has become a standard treatment for advanced BRAF mutated

malignant melanomas, clinicians need to be vigilant for early

onset Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Of the 3 available BRAF/MEKi

combination; Vemurafenib-Cobimetinib (Roche) having the highest

skin toxicities (78%), and Dabrafenib-Trametinib with 58% skin

toxicities, and Encorafenib-Binimetinib with the least recorded

incidence 24%.

Conclusion

The possibility of check point inhibitor prior to BRAF/MEKinhibitor blockade as a cause is high likely a causality of TENs. This is due to alternative mechanism than direct T -cell-drug/MHC recognition. In her case, the earlier exposure to immunotherapy and later targeted therapy could have exacerbate the adverse effect.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Harr T, French LE (2010) Severe cutaneous adverse reactions: acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Med Clin North Am 94(4): 727-42, x.

- Greco A, Safi D, Swami U, Ginader T, Milhem M, et al. (2019) Efficacy and adverse events in metastatic melanoma patients treated with combination BRAF plus MEK inhibitors versus BRAF inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Cancers 11(12): 1950.

- Heppt MV, Siepmann T, Engel J, Schubert-Fritschle G, Eckel R, et al. (2017) Prognostic significance of BRAF and NRAS mutations in melanoma: a German study from routine care. BMC Cancer 17(1): 536.

- Tahseen AI, Patel NB (2018) Successful dabrafenib transition after vemurafenib-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in a patient with metastatic melanoma. JAAD Case Rep 4(9): 930-933.

- Torres‐Navarro I, De Unamuno‐Bustos B, Botella‐Estrada R (2020) Systematic review of BRAF/MEK inhibitors‐induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 35(3): 607-614.

© 2021 Chit Cheng Yeoh. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)