- Submissions

Full Text

Advancements in Case Studies

External Jugular Vein Terminates in Cephalic Vein, an Anatomical Variation During Neck Dissection & its Clinical Impact

Leah Fecik* and Abdulsattar Abdulrahman

Chatham University, USA

*Corresponding author:Leah Fecik, Chatham University, USA

Submission: November 13, 2019;Published: November 20, 2019

ISSN 2639-0531Volume2 Issue2

Abstract

Background: Measles remains one of the leading causes of death among children around the world. Encephalitis is the most serious complication of measles virus infection.

Case presentation: We report two measles-induced encephalitis who was admitted to to Kyiv City Pediatric Infectious Clinical Hospital. One patient had postinfectious variant of measles encephalitis that occurred 6 days after primary measles infection onset. Disease had benign course with substantial improvement during hospital stay. Another patient presented with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Neurological symptoms started 10 years after measles infection. Disease characterized by progredient course and unfavorable outcome.

Conclusion: Measles encephalitis is rare but serious and often deadliest complication. It should be considered in differential diagnostic of CNS infection among pediatric patients. Keywords: Measles, Encephalitis, Children

Introduction

With the advanced technology and instrumentation utilized in medical practice, precise interventional radiology & implantation of an artificial cardiac pacemaker [1], in addition to orthopedic surgeons dealing with fracture and dislocation of the clavicle, it is valid to know different forms of variations of the venous tree in the lower neck. Anatomically, facial veins join retromandibular and posterior auricular veins forming the external jugular vein (EJV), which throughout its course runs deep to superficial fascia and platysma muscle. In the lower posterior triangle of the neck, both (EJVs) end in subclavian veins (SV) after piercing the investing layer of deep fascia lateral to the sternoclavicular joint [2]. Developmentally, between 4th & 7th weeks of embryonic life anterior cardinal veins appear, those veins drain the cephalic part of the embryo; blood will be channeled from left to right as a lot of anastomosing channels exist between the anterior cardinal veins, this anastomosis eventually forms the left brachiocephalic vein [3]. The full idea about venous drainage map in the lower neck is vital in central venous line insertion and surgical access incisions as well as internal fixation of fractured clavicles in certain occasions. Main focus of this work is to highlight specific points regarding the anatomical variation of the venous channel in the lower neck, which is vital for clinicians, surgeons, and radiologists.

Case Report

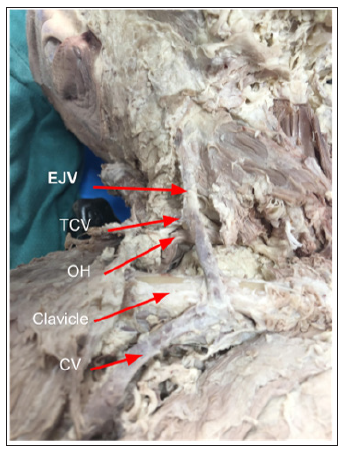

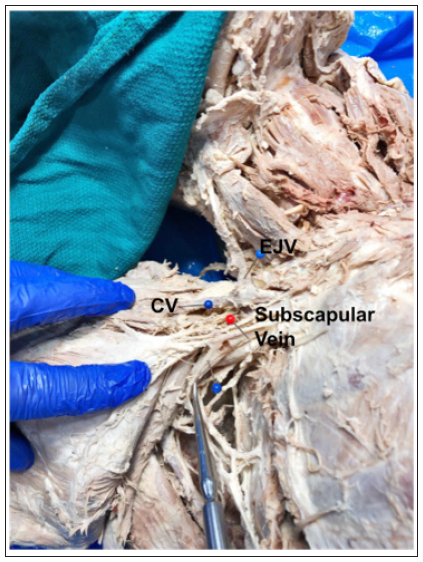

While completing a routine human cadaver dissection lab, at the graduate-level, in the Department of Biology at Chatham University (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), we discovered an unusual unilateral variation in the course of the right EJV, in a 72-year-old female. An iPhone 7 mobile phone was utilized to photograph the case (Figure 1). The following findings were observed: these right-sided vessels appear larger than the left side, the EJV runs over the clavicle & joins the terminal part of the cephalic vein (CV). The transverse cervical vein (TCV) is located superficial to the omohyoid muscle (OH). Deep dissection of axilla shows angiogenesis of axillary vein as the brachial veins continue proximally joining the cephalic vein, large subscapular vein substitutes axillary vein (Figure 2).

Discussion

There have been numerous EJV variations noted in past literature; previous variations observed included abnormalities in both the confluence of the EJV as well as the location [4]. In terms of confluences, the EJV was seen to divide forming two loops that rejoin prior to draining into the SV [5]. In another case, the EJV structure varied as it bifurcated into two vessels that did not rejoin prior to draining into the SV and the two vessels were larger in size than the average EJV [6]. Variations in the veins draining into the EJV have also been observed such that the retromandibular vein does not divide into anterior and posterior divisions and remains as one trunk that has a connection with the facial vein [7].

Figure 1:External jugular vein drains directly into cephalic vein and lies superficial to clavicle. Transverse cervical vein lies superficial to omohyoid muscle.

Figure 2:Enlarged subscapular vein substitutes as the axillary vein.

The EJV has been seen to join with the cephalic vein and lie anterior to the clavicle; in a study of 55 cadavers, between 2 and 5 percent of the cadavers had this structure [8]. These findings are very much similar to the present findings in that the EJV joins with the CV and lies anterior to the clavicle. The present case differs in that, in addition to the EJV and CV connecting and lying superficially, the TCV is also located superficially as it passes anterior to the OH muscle, the brachial veins drain into the cephalic vein, and the subscapular vein is large in size and substitutes as the axillary vein. A review of the literature did not find any sources in which all of these findings occurred simultaneously.

It is important to consider these anatomical variations when performing procedures, interventions, & surgical fixation of fractured clavicle. A procedure that involves the head and neck regions, where these variations have been noted, is the repair of clavicular fracture through orthopedic surgery. Clavicle fractures comprise up to 5% of all adult fractures; they most commonly occur over the mid-shaft, and then the medial ⅓, and least commonly occur over the distal ⅓ of the clavicle [9,10]. It was seen that surgical intervention, as opposed to nonsurgical treatment, improved prognosis in patients experiencing a mid-shaft clavicular fracture [11]. The variations noted in this present case report involve the EJV and CV laying superficial to the medial ⅓ of the clavicle; both a fracture to the clavicle and surgical intervention would put these venous structures at risk for injury.

Access through the CV, by means of venous cutdown, is commonly used for lead implantation of cardiac devices and is favorable as it has been seen to pose less risk compared to other techniques [12]. Variations in the CV can occur and result in higher failure rates due to difficulty distinguishing the vessels and passage failure; enlarged vessels and abnormal connections can result in the CV becoming the dominant vein of the arm, which can lead to venous occlusion and additional complications [13]. Variations, such as the ones discussed currently, should be considered when performing venography and lead implantation as success rates and complications can be influenced.

Access through the CV, by means of venous cutdown, is commonly used for lead implantation of cardiac devices and is favorable as it has been seen to pose less risk compared to other techniques [12]. CV variations can include abnormal venous confluences and the possibility of a decrease in vascular caliber. These variations can result in higher failure rates due to difficulty distinguishing the vessels and passage failure; enlarged vessels and abnormal connections can result in the CV becoming the dominant vein of the arm, which can lead to venous occlusion and additional complications [13]. In order to anticipate such variations, venography should be performed prior to surgical interventions, however, this is a costly procedure that makes it impractical to perform as a routine measure. Variations, such as the ones discussed currently, should be considered when performing lead implantation as success rates and complications can be influenced.

References

- Shimada H, Hoshino K, Yuki M, Sakurai S, Owa M (1999) Percutaneous cephalic vein approach for permanent pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 22(10): 1499-1501.

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM (2005) Gray’s anatomy for students. Churchill Livingstone, UK.

- Sadler TW, Langman, J (2004) Langman’s medical embryology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

- Dalip D, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS (2018) Review of the variations of the superficial veins of the neck. Cureus 10(6): e2826.

- Vani PC, Rajasekhar SSSN, Gladwin V (2019) Unusual and multiple variations of head and neck veins: a case report. Surg Radiol Anat 41(5): 535-538.

- Rao S, Pandey S, Kumar Y, Rao S (2018) Bifurcation of external jugular vein: an anatomical variation during neck dissection. Oral Maxillofac Surg 22(4): 475-476.

- Ghosh S, Mandal L, Roy S, Bandyopadhyay M (2012) Two rare anatomical variations of external jugular vein: An embryological overview. International Journal of Morphology 30: 821-824.

- Kameda S, Tanaka O, Terayama H, Kanazawa T, Sakamoto R, et al. (2018) Variations of the cephalic vein anterior to the clavicle in humans. Folia Morphol 77(4): 677-682.

- Robinson CM (1998) Fractures of the clavicle in the adult: Epidemiology and classification. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 80(3): 476-484.

- Bentley TP, Journey JD (2019) Clavicle Fractures. In Stat Pearls.

- Guerra E, Previtali D, Tamborini S, Filardo G, Zaffagnini S, et al. (2019) Midshaft clavicle fractures: Surgery provides better results as compared with nonoperative treatment: A meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med

- Benz AP, Vamos M, Erath JW, Hohnloser SH (2019) Cephalic vs. subclavian lead implantation in cardiac implantable electronic devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 21(1): 121-129.

- Steckiewicz R, Świętoń E, Stolarz P, Grabowski M (2015) Clinical implications of cephalic vein morphometry in routine cardiac implantable electronic device insertion. Folia Morphol 74(4): 458-464.

© 2019 Leah Fecik. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)