- Submissions

Full Text

Advancements in Case Studies

Cholecysto-Colic Fistula: Case Report

Momcilo Stosic*

Department of Surgery, Health Center, Serbia

*Corresponding author: Momcilo Stosic, MD, PhD, Department of surgery, Health Center, Vojvode Misica 17, 7500 Vranje, Serbia

Submission: October 16, 2017;Published: May 16, 2018

ISSN 2639-0531Volume1 Issue2

Abstract

Chronic diarrhea as a result of colonic fistulas -two case reports with different origin. When it comes to chronic diarrhea symptom, the first thing one thinks of is never a surgical cause, but an infectious disease. The aim of this paper is to show 2 different cases of chronic diarrhea, resulting from benign surgical causes - colonic fistula. The first case is a result of cholecystocolic fistula, while the second is the result of gastrojejunocolic fistula. Colonic fistulas originate from different causes: malignancy, NSAID, diverticulosis of the colon, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, lymphoma, or after radiation therapy. They can also result from a trauma, which can be post-surgical.

Introduction: Cholecystocolic fistula occurs as a result of the inflammation of the gallbladder. It arises from existing adhesions. The incidence rate is not high, but the complication is not a rarity per se. It is less frequent complication than cholecystoduodenal fistula. The main symptoms are secretory diarrhea, vitamin K malabsorption and weight loss, and thus suspicion of malignancy is usual. The treatment is surgical removal of the gallbladder, fistula and part of the colon en bloc.

Case report: A 73-year old male patient was admitted to the department after 5 months of medical treatment. Laboratory tests, coproculture, colonoscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, and gastroduodenoscopy were performed - the diagnosis was not established. The diagnosis was made by means of irrigography and short and narrow cholecystocolic fistula was confirmed. The possibility of malignant disease was not completely excluded. The patient underwent surgery after parental nutrition-adhesions, gallbladder, and the prepared fistula were removed as well as the longitudinal part of the transverse colon, which was simultaneously repaired. Ex-tempore diagnosis-the surgical specimen originated from inflammation, not from malignancy. The post-operative course was uneventful. The first post-operative stool was normal. The patient gained some weight after a few months.

Conclusion: Along with the contemporary diagnostics methods, contrast examination plays an important diagnostic role. When infection is excluded as the cause of chronic diarrhea, cholecystocolic fistula should be considered. Malignant disease should be excluded before the surgery, or it may be diagnosed during the surgery, which would determine the course of the treatment. The treatment of benign cholecystocolic fistula is surgical en bloc procedure.

Introduction

The incidence rate of cholecystocolic fistula (CCF) is low and it accounts for 0.06-0.14% of all biliary diseases [1]. In 2009, an extensive review was published and it listed a total of 231 cases reported in medical studies between 1950 and 2006. The key symptoms are chronic diarrhea and a progressive weight loss, which can be associated with malignancy [2].

Case Report

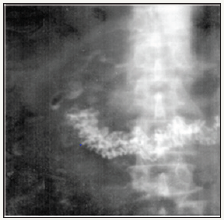

A 73-year old man was presented with these symptoms: during the last 5 months, he suffered from 5-6 watery stools a day. He lost weight. He had experienced pain below the right rib arch, but the pain ceased with the diarrhea. He did not report any other symptoms apart from diarrhea and physical fatigue. He never suffered from jaundice. Stool tests, both microscopic and coproculture, did not show any bacteria (Shigella, Salmonella) or viral pathogens, which cause enterocolitis [3]. Conjugated bilirubin was 5μmol/L, total 17μmol/L. Laboratory tests were within normal range, including albumin and protein; leucocytosis was 13000/μL. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed crumpled gallbladder with calculosis. Gastroduodenography results and passage of the small intestine were normal. Colonoscopy showed no abnormalities. Computerized tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen did not show fistula as well. The diagnosis was reached after irrigography: the contrast entered the gallbladder and biliary tract (Figure 1) [4].

Figure 1: Contrast goes through the fistula into biliary tract after irrigography, pneumobilia.

The surgery was done while bearing in mind the fact that there might be possible malignant cause of the fistula. Short and narrow fistula was found intraoperatively. After ligature of d.cysticus and gallbladder preparation, wide lateral excision of the colon transversum with the fistula was performed en bloc. The colon was sutured [5]. Ex-tempore histopathologic examination of the specimen excluded malignancy. The passage was established on the 3rd post-operative day, and the patient was discharged on the 11th post-operative day. The first stool was of regular consistency [6]. During the following month, the patient gained 3 kg.

Discussion

Cholecystitis may form growths to the surrounding organs such as stomach, duodenum or colon. Over time, the growths may result in fistula, i.e. communication between 2 hollow organs. The majority of CCF is discovered intra operatively. In the case presented, the diagnosis was made preoperatively, which facilitated the planning of the surgical procedure. The preoperative diagnosis of CCF accounts for only 7, 9% of all cases.

The incidence is low: 1CCF in every 1000 cholecystectomies. The terms “fistula” and “gallstone ileus” were used in matching search of the Medline service, and 160 articles were found, dating from 1950 to 2006, all concerning a total of 231 cases [7]. Some of the cases, although rare ones, resulted in acute obstruction, mainly in sigmoid. The reason for this may be the discrepancy between the calculus which passes through the fistula and the colon itself. Some patients are diagnosed with squamous cellular carcinoma (SCC) of the gallbladder, which leads to conclusion that the number of inflammation caused fistula is even smaller. The rate of malignant diseases which cause these fistulasis up to 15%.

Pathognomonic triad of symptoms includes chronic diarrhea, pneumobilia, and vitamin K malabsorption . Our patient presented with pneumobilia and chronic diarrhea. The weight loss was also present, which may be considered as the fourth symptom. Despite the modern diagnostics procedures, we reached the diagnosis by means of contrast examination-irrigography (barium enema). In our case, the patient showed no other symptoms apart from persistent and long-lasting diarrhea. Drainage of bale (and calculus possibly) through the fistula into the colon resolves the symptomatology of the gallbladder. Simultaneously, the presence of bile salt in the colon causes secretory diarrhea [8]. On the other hand, the by-pass of the bile into the transverse colon results in absence of bile in the terminal ileum, where it is usually reabsorbed together with D, E, K and A vitamins.

The treatment is surgical, which had been contraindicated for laparoscopic surgeries for a long time. Recently, open and laparoscopic surgeries have been equally justified, depending on the skills of the surgeon who does the laparoscopic procedure. Conversion is performed depending on the local findings. The modern methods of colic fistula closure have been recently reported, and the procedure may be used in cases of CCF [9,10].

Conclusion

The triad of symptoms, together with weight loss, may indicate the diagnoses. The chronic diarrhea symptom with no inflammation causes, malignant cause or other causes is highlighted. Along with modern diagnostics methods (CT, colonoscopy with biopsy, capsule endoscopy), the classic contrast examination should not be disregarded. The treatment is surgical.

References

- Goldberg JB, Moses RA, Holubar SD (2012) Colosplenic Fistula: a Highly Unusual Colonic Fistula. J Gastrointest Surg 16(12): 2338-2340.

- Chintapatla S, Scott NA (2003) Management of Intestinal Fistulas. In: Common abdominal conditions 43-49.

- Balent E, Plackett TP, Lin HK (2012) Cholecystocolonic Fistula. Hawaii J Med Public Health 71(6): 155-157.

- Costi R, Randone B, Violi V, Scatton O, Sarli L, et al. (2009) Cholecystocolonic fistula: facts and myths. A review of the 231 published cases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 16(1): 8-18.

- Fujitani K, Hasuike Y, Tsujinaka T, Mishima H, Takeda Y, et al. (2001) New Technique of Laparoscopic-Assisted Excision of a Cholecystocolic Fistula: Report of a Case. Surgery Today 31(8): 740-742.

- Gora N, Singh A, Jain S, Parihar US, Bhutra S (2014) Spontaneous Cholecystocolic Fistula: Case Report. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 8(3):164-165.

- Savvidou S, Goulis J, Gantzarou A, Ilonidis G (2009) Pneumobilia, chronic diarrhoea, vitamin K mal absorption: a pathognomonic triad for cholecystocolonic fistulas. World J Gastroenterol 15(32): 4077-4082.

- Colovic R, Dordevic D, Colovic M (1987) Cholecystocolonic fistula (2 case reports). Acta Chir Iugosl 34(2): 160-166.

- Prasad A, Foley RJE (1994) Laparoscopic management of cholecystocolic fistula. British Journal of Surgery 81(12):1789-1790.

- Su CH, Yu FJ, Tsai HL, Wang JY (2014) Endoscopic closure of colonic fistulas in colon cancer patients using a combination of hemoclips and endoloops: two case reports. Techniques in Coloproctology 18(2): 205- 208.

© 2018 Momcilo Stosic. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)