- Submissions

Full Text

Advances in Complementary & Alternative medicine

Effects of Fasting on Anxiety: A Literature Review

Abdalla Nedal, Osama Razouk, Jana Samara, Alyamama Alnamous, Saif Almuzainy, Rashid Abu Helwa, Sara Nameer, Rayan Aljubeh and Mohamed Sidi*

College of Medicine, University of Sharjah, UAE

*Corresponding author:Mohamed Sidi, College of Medicine, University of Sharjah,UAE

Submission: March 23, 2024;Published: April 01, 2024

ISSN: 2637-7802 Volume 8 Issue 2

Abstract

Background: While some research studies show that fasting is associated with poor psychological health

outcomes, others suggest otherwise. This led to an increasing body of knowledge to resolve this conflict.

Despite this, no study has been done to strictly investigate the relationship between fasting and anxiety

as a measure of psychological health. Therefore, this present study aims to explore the effect of fasting on

anxiety, disregarding other variables.

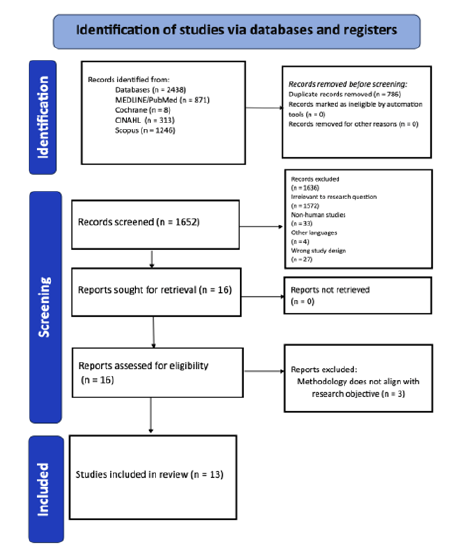

Methods: A comprehensive search strategy was run. The search strategy involved the following keywords

and their synonyms: fasting, intermittent fasting, meal skipping, alternate-day fasting, time-restricted

feeding, time-restricted eating, reduced meal frequency, and fasted state for fasting. For anxiety, anxiety,

phobia, and panic were used as search terms. Only studies in English were included. Medline, Cochrane

Library, CINAHL, and Scopus were searched between 2000 and 2024. 1652 research articles were

retrieved. Articles were screened by two investigators. In the case of a disagreement, a third investigator

was sought to resolve the conflict. Following screening, 13 studies were included.

Result: The review indicates a complex relationship between fasting and anxiety levels. The majority of

studies found a negative association between fasting and anxiety, where fasting periods were correlated

with decreased anxiety levels. On the other hand, two studies found a positive association between stress

and fasting. Two studies found no association or varying effects, pointing to possible variability based

on individual factors such as age, gender, occupation, and pre-existing health conditions. Overall, the

outcomes are not uniform across all fasting types and populations.

Conclusion: The results of this review show that fasting is associated with reduced anxiety levels. More

studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms underlying these effects and investigate the possibility

of more extensive integration of fasting practices into mental health interventions.

Keywords:Onychomycosis; Dermatophytes; Environment; Antiseptic

Introduction

Fasting has always been part of different cultures and has been found in religious practices since 1500 B.C. [1]. It has always been seen as a big part and plays a significant role in many Muslims’ lives [2]. Although with a more accessible alternative, around 50% of the pregnant population choose to fast during the holy month of Ramadan [3]. This shows the sheer dedication and importance of fasting in the Muslim community, mainly during Ramadan. Anxiety is a disorder that includes a multitude of presentations, some of which are excessive worrying, social fear, performance fear, nervousness, restlessness, irritability, and fatigue physical symptoms such as muscle tension, chest pain, and heart racing could be present as well [4]. Recent updates in the DSM-5 to diagnose General Anxiety Disorder (GAD), a presentation of 3 or more of the symptoms mentioned should be there for 6 months or more [5]. The presence of such anxiety symptoms was seen to have a negative association with healthcare students [6-8].

Methodology

Search strategy

Our review was conducted with the objective of identifying peer-reviewed journal articles that investigated the relationship between various fasting regimens and anxiety levels. The search was carried out across four electronic databases: PubMed/ Medline, Cochrane, Cinahl, and Scopus. The time frame for the literature search extended from January 1, 2000, to February 13, 2024. The search was executed in February 2024, yielding a total of 2438 articles: 871 from PubMed/Medline, 8 from Cochrane, 313 from Cinahl, and 1246 from Scopus. Duplicates were first removed, resulting in the exclusion of 786 articles. The remaining 1652 articles underwent title and abstract screening, which was independently conducted by two researchers to ensure the accuracy of study selection. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus, involving a third reviewer when necessary. This initial screening narrowed the pool to 16 articles, from which a full-text review was carried out to determine the final selection. Ultimately, 13 articles met all the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The search strategy employed a combination of key terms related to fasting and anxiety. The keywords used included (“Fasting” or “Intermittent fasting” or “Alternate day fasting” or “Meal skipping” or “Time restricted feeding” or “Time restricted eating” or “Reduced meal frequency” or “Fasted state”) and (“Anxiety” or “Panic” or “Phobia”).

Study selection Inclusion criteria:

A. Peer-reviewed research articles, including Randomized

Controlled Trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies,

and cross-sectional studies.

B. Studies involving human subjects of any age, sex, ethnicity,

and socioeconomic status

C. Studies that specifically examine the impact of any form of

fasting on anxiety levels.

D. Studies must measure anxiety as a primary or secondary

outcome, using validated instruments or diagnostic criteria.

E. Published between 1/1/2000 and 13/2/2024, in English,

and is included in the searched databases.

Exclusion criteria:

a) Articles that were not primary research studies, such as

editorials, letters, comments, conference abstracts, reviews

(systematic, narrative), meta-analyses, case reports, and book

chapters.

b) Studies that focus on dietary restrictions not clearly

defined as fasting (such as caloric restriction diets without

fasting periods) or not directly examining the relationship

between fasting and anxiety.

c) Studies that do not have a clear measurement of anxiety

or use unvalidated tools for assessing anxiety.

d) Non-English language studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Identification of studies via databases and registers.

Result

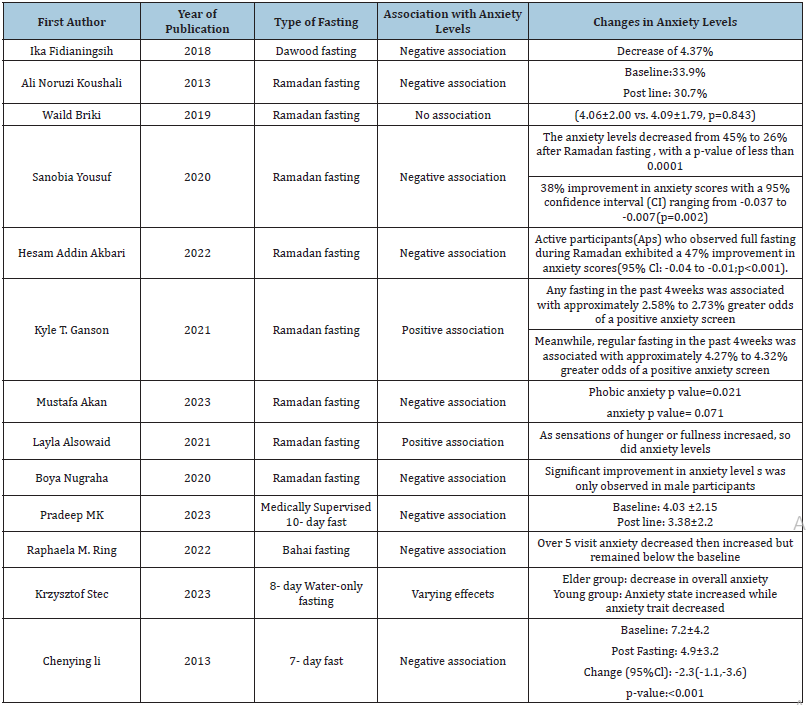

Ramadan fasting

Ramadan fasting’s impact on anxiety levels is a multifaceted subject explored through several studies. A study by Noruzi Koushali et al. investigated nurses’ mental health post-Ramadan fasting, revealing a noteworthy reduction in depression and stress levels [9]. Although anxiety levels also decreased, the change was not statistically significant, suggesting a potential yet inconclusive positive trend. In a study by Akbari et al. [10] during the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals who fully observed Ramadan fasting exhibited substantial improvements in anxiety scores, with Inactive Participants (IPs) showing a 38% improvement and Active Participants (APs) experiencing a 47% improvement in anxiety scores, highlighting the dose-response relationship between fasting extent and anxiety reduction [10]. Sanobia Y et al. [11] research among individuals with diabetes demonstrated a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms post-Ramadan fasting, with the fasting group reporting only 26% of participants with anxiety symptoms compared to 40% in the non-fasting group, showcasing a substantial improvement in anxiety outcomes [11].

Furthermore, the study by Hesam Addin Akbari explored the association of Ramadan participation with psychological parameters during the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing significant improvements in anxiety outcomes among individuals who fully observed fasting compared to non-fasters [10]. Additionally, Boya Nugraha et al. [12] clinical trial among young males and females found an overall trend toward improved anxiety scores post-fasting, particularly in males, aligning with prior research indicating a more pronounced response to fasting regarding anxiety reduction [12]. Layla Alsowaid et al. [13] study among female students uncovered a strong correlation between hunger/fullness sensations and anxiety levels during Ramadan fasting, underscoring the intricate interplay between physiological and psychological factors during fasting [13]. Additionally, a pilot study assessing the impact of Ramadan fasting on anxiety among healthy Muslim participants found no significant effect on anxiety levels. The research included 83 individuals from both Muslim-majority and non-Muslim-majority countries, indicating that Ramadan fasting did not significantly alter anxiety levels [14]. This study’s findings suggest that while Ramadan fasting may lead to reduced levels of positive affect and depression, it does not appear to have a specific influence on anxiety among healthy Muslim individuals. These studies collectively underscore the complex nature of Ramadan fasting’s impact on anxiety, with some showing significant improvements while others reveal nuanced changes or no significant effects. The varying results highlight the need for further research to comprehensively understand how Ramadan fasting influences anxiety levels across diverse populations and contexts (Table 1).

Table 1:Summary of the finding..

Other fasting practices

The impact of fasting on anxiety extends beyond Ramadan, as evidenced by various studies exploring different fasting programs. A study by Pradeep MK et al. [15] focused on a 10-day medically supervised fast, revealing a statistically significant reduction in anxiety levels among participants completing the fasting regimen, showcasing the potential benefits of structured fasting on anxiety outcomes [15]. Chenying Li et al. [16] research among obese patients examined the physiological and psychological responses to a 7-day fasting program, observing substantial improvements in anxiety and depression, along with enhanced mood and reduced fatigue among participants [16]. Furthermore, Raphaela M R et al. [17] study on Bahá’í fasting highlighted the positive effects of religiously motivated intermittent fasting on anxiety reduction, emphasizing the role of spiritual faith and social support in managing anxiety during fasting periods [17]. Additionally, Krzysztof Stec et al. [18] investigation into an 8-day water-only fasting regimen found varying effects on different forms of anxiety, indicating a nuanced relationship between fasting duration and anxiety outcomes [18]. Moreover, Mustafa A et al. [19] study among healthcare professionals revealed a statistically significant reduction in specific anxiety-related symptoms post-Ramadan fasting, emphasizing the potential impact of fasting on specific aspects of anxiety [19]. Also, a study by Ali Noruzi Koushali et al. [9] explored the effects of Dawood fasting on emotional reactions in nurses, showing significant improvements in depression and stress levels post-fasting, although the reduction in anxiety levels was not statistically significant [9].

Additionally, Research indicates that fasting behaviours are associated with increased anxiety among college students, with both occasional and regular fasting linked to a higher likelihood of exhibiting anxiety symptoms [20]. Finally, Dawood fasting for 22 days led to a 4.37% decline in anxiety symptoms, attributed to reduced noradrenaline levels and modulation of the sympathetic nervous system, improving sleep and indirectly benefiting anxiety management [21]. Despite variations in outcomes, fasting consistently decreased anxiety scores post-fasting, supported by physiological effects like HPA modulation, cortisol reduction, and increased beta-endorphins associated with comfort and anxiety alleviation, highlighting the connection between fasting and anxiety reduction (Decreased anxiety after Dawood fasting in the pre-elderly and elderly). These diverse findings highlight the complex interplay between fasting programs and anxiety outcomes, underscoring the need for further research to elucidate the mechanisms and optimize the therapeutic potential of fasting in managing anxiety across different populations and fasting modalities.

Conclusion

The relationship between fasting and anxiety is intricate, with studies on Ramadan fasting revealing mixed results in anxiety reduction, indicating potential yet inconclusive positive trends. Other fasting practices, such as medically supervised fasts and religiously motivated fasting, also show varying impacts on anxiety levels across different populations. While some studies highlight significant improvements, particularly with more extensive fasting, the nuanced nature of these findings emphasizes the need for further research to understand fasting’s therapeutic potential in managing anxiety comprehensively.

References

- LaFountain R (2023) The history of fasting.

- Helwa A, Razouk R, Hamdan O, Alkhalidi S, Bonny M, et al. (2024) A mini-review: Investigating the interplay of maternal diet, fasting in Ramadan, and their collective impact on pregnancy and fetal outcomes. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 55(2): 46826-46831.

- Joosoph J, Abu J, Yu SL (2004) A survey of fasting during pregnancy. Singapore Medical Journal 45(12): 583-586.

- DeMartini J, Patel G, Fancher TL (2019) Generalized anxiety disorder. Annals of Internal Medicine 170(7): ITC49-ITC64.

- First MB (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, and clinical utility. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 201(9): 727-729.

- Karagol A (2021) Levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life of medical students. Psychiatria Danubina 33(Suppl 4): 732-737.

- Gan GG, Ling HY (2019) Anxiety, depression and quality of life of medical students in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 74(1): 57-61.

- Freitas PHBD, Meireles AL, Ribeiro IKdS, Abreu MNS, Paula Wd, et al. (2023) Symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress in healthy students and impact on quality of life. Latin American Nursing Magazine 31: e3884.

- Koushali AN, Hajiamini Z, Ebadi A, Bayat N, Khamseh F (2013) Effect of Ramadan fasting on emotional reactions in nurses. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 18(3): 232-236.

- Akbari HA, Yoosefi M, Pourabbas M, Weiss K, Knechtle B, et al. (2022) Association of Ramadan participation with psychological parameters: A cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Journal of Clinical Medicine 11(9): 2346.

- Yousuf S, Syed A, Ahmedani MY (2021) To explore the association of Ramadan fasting with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in people with diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 172: 108545.

- Nugraha B, Riat A, Ghashang SK, Eljurnazi L, Gutenbrunner C (2020) A prospective clinical trial of prolonged fasting in healthy young males and females-effect on fatigue, sleepiness, mood and body composition. Nutrients 12(8): 2281.

- Alsowaid L, Perna S, Peroni G, Gasparri C, Alalwan TA, et al. (2021) Multidimensional evaluation of the effects of Ramadan intermittent fasting on the health of female students at the University of Bahrain. Arab Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 28(1): 360-369.

- Briki W, Aloui A, Bragazzi NL, Chamari K (2019) The buffering effect of Ramadan fasting on emotions intensity: A pilot study. Tunis Med 97(10): 1187-1191.

- Pradeep M, Kodali P, Tewani G, Sharma H, Aarti N (2023) Physiological and psychological effects of medically supervised fasting in young female adults: An observational study. Curēus 15(7): e42183.

- Li C, Ostermann T, Hardt M, Lüdtke R, Preuss BM, et al. (2013) Metabolic and psychological response to 7-day fasting in obese patients with and without metabolic syndrome. Research Complement Med 20(6): 413-420.

- Ring RM, Eisenmann C, Kandil FI, Steckhan N, Demmrich S, et al. (2022) Mental and behavioural responses to Bahá’í fasting: looking behind the scenes of a religiously motivated intermittent fast using a mixed methods approach. Nutrients 14(5): 1038.

- Stec K, Pilis K, Pilis W, Dolibog P, Letkiewicz S, et al. (2023) Effects of fasting on the physiological and psychological responses in middle-aged men. Nutrients Aug 15(15): 3444.

- Akan M, Unal S, Erbay GL, Taskapan MC (2023) The effect of Ramadan fasting on mental health and some hormonal levels in healthy males. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 59(1): 20-29.

- Ganson KT, Rodgers RF, Murray SB, Nagata JM (2021) Prevalence and demographic, substance use, and mental health correlates of fasting among U.S. college students. J Eat Disord 9(1): 88.

- Fidianingsih I, Jamil NA, Andriani RN, Rindra WM (2018) Decreased anxiety after Dawood fasting in the pre-elderly and elderly. J Complement Integr Med 16(1): 57.

© 2024 Mohamed Sidi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)