- Submissions

Full Text

Advances in Complementary & Alternative medicine

Acupuncture (Needle Only) Versus Neural Therapy by Huneke (Therapeutic Local Anesthesia) in the Treatment of the Painful Shoulder: Immediate and Long-Term Results (4 Years)

Paolo Barbagli1,3*, Renza Bollettin1,3, Veronica Gagliardi2 and Francesco Ceccherelli2,3

1Outpatient Pain Therapy Center, Italy

2Pain Therapy Clinic, Italy

2A.I.R.A.S. (Italian Association for Research and Scientific Updates - Italian Association for Research and Scientific Updates), Italy

*Corresponding author:Paolo Barbagli, Outpatient Pain Therapy Center, 58/b Dante Alighieri Avenue, Riva del Garda (Trento), Italy

Submission: June 22, 2023;Published: July 07, 2023

ISSN: 2637-7802 Volume 7 Issue 5

Abstract

Background: Acupuncture, consisting of the insertion of needles in the specific acupuncture points, and neural therapy by Huneke (NT), which is the subcutaneous or intramuscular injection of a local anesthetic in trigger/tender points almost always on acupuncture points, are two potentially effective therapeutic techniques in the treatment of the painful shoulder. The purpose of this retrospective study is to compare the short and long-term results of these two reflexology techniques in the treatment of the painful shoulder.

Methods: Pain related results obtained from 1982 to 2007 from two groups, one treated with acupuncture (N=47), the other treated with Neural Therapy (NT) by Huneke (N=228), have been compared assessing two indexes of analgesic effectiveness, the Subjective Pain Relief Percentage (SPRP) every 3 months for 4 years, and the Time of average persistence of the result, in cases successfully treated and with follow-up of at least 2 years (TAPR≥2y).

Results: The two groups are comparable for pain duration, number of sessions, and duration of the treatment cycle, even though the “NT” group is older. The analgesic results of the two groups were not statistically different, but the majority of indexes of analgesic effectiveness examined resulted better in the “NT” group. In particular, the initial SPRP was 63.9% (acupuncture) and 66.2% (NT), whereas the TAPR≥2y was 27.4 months (acupuncture) and 37.8 months (NT).

Conclusion: Both therapeutic techniques examined are potentially effective. Neventheless, neural therapy has beeen detected slightly superior, especially after the two years of follow-up.

Keywords:Acupuncture; Painful shoulder; Neural therapy; Local anesthetics

Introduction

The painful shoulder, or rather the scapulohumeral periarthritis, as it was defined by Duplay in 1872, is a very frequent pain syndrome, including different nosological entities, which is mainly characterized by pain and/or difficulty in usual movements. One of the diagnostic systems identifies various tendinopathies, such as rotator cuff tear, biceps or supraspinatus tendinitis that can evolve in capsulitis of the shoulder (frozen shoulder), and it is widely used, as described by Consensus Group Delphi in 1997 [1]. However, there is a low grade of diagnostic agreement among different practitioners, which in several studies do not reach 50% [2,3]. A widely used classification is the one of Neer [4], who in 1972 defined the disorder as Subacromial conflict syndrome (“impingement syndrome”) and divided it in three stages of increasing severity. According to this etiopathogenetic hypothesis, the rotator cuff (consisting of the subscapularis tendons, the long head of biceps, the infraspinatus, supraspinatus and teres minor), is damaged because of degenerative or traumatic phenomena, causing a deficit in stabilizing and centering the humerus head in the glenoid cavity (glenoid-humerus articulation). The lack of this function leads to the tendency of the humerus head to slide with each arm movement, with a consequent constant microtraumatism of the head of the humerus itself and of the coracoacromial ligament (“conflict” or “impingement”), with further degenerative phenomena of the head of the humerus (erosion, resorption, reactive sclerosis), periarticular inflammatory phenomena with progressive pain worsening. The risk factors for this pathophysiological mechanism are mechanical overload, stress, obesity, age and feminine sex, while sports activities and movement in general are protective factors [5,6]. In addition, psychosocial and individual factors help to develop and maintain the pain pathology [7-8]. The painful shoulder often tends to be selfhealing, but recent studies stress the heavy impact on the quality of life and the serious work and social consequences [9], which in half of the cases at least last several years [10]. Different therapeutic approaches are in use in daily medical practice, but they remain controversial. The most recent critical reviews [11-17] try to find evidence of effectiveness in various therapies, so we do not have sufficient data to assess the examined treatments. In particular, the above-mentioned treatments are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular or subacromial glucocorticosteroid injection, oral glucocorticosteroid treatment, physiotherapy, manipulation under anesthesia, hydrodilatation, or surgery [14], “corticosteroid injections [15], ultrasound, laser therapy and magnetotherapy [16].

Of all the reflexology and/or complementary techniques, acupuncture is undoubtedly the most studied, which is also the object of a critical review of literature, which concludes that there is little evidence to support or refute the use of acupuncture for shoulder pain [17]. The results obtained by the authors with two reflexology methods - acupuncture [18], or the insertion of needles at certain cutaneous points called acupuncture points, and Neural Therapy (NT) by Huneke [19-23], which is the injection in the same points of low doses of a local anesthetic, almost always procaine or lidocaine in subanesthetic concentration (usually 0.5%) by wheals or intramuscular infiltration, are reported and compared here. Acupuncture is a millenary technique born in China and proved to be particularly useful in the treatment of benign pain [24]. Some Chinese [25-27] and Western [28-32] studies suggest, without conclusive evidence, its possible effectiveness even in the treatment of the painful shoulder. The Neural Therapy (NT) by Huneke is a therapeutic method born in Germany in the ‘20 and practiced with this name in German-speaking countries, even though present in many other countries, such as Latin America and Spain. It consists of infiltration of small doses (0.5-1cc) of local anesthetic at low concentrations (1% procaine or 0.5% lidocaine) in the acupuncture and trigger/tender points (with wheals or intramuscular), as well as in many other anatomical structures such as the arteries and veins, the nervous plexuses or individual peripheral nerves, joints, etc; or in anatomical structures as scars, teeth, tonsils (in order of frequency) etc, when considered “interference fields”. In Englishspeaking countries, the therapeutic use of local anesthetics is widespread, but without the name of “neural therapy”, especially systemically [33], transnasally [34,35] and in trigger/tender points [36,37]. Several studies on neural therapy, although mostly case studies and open studies, suggest their usefulness in musculoskeletal pain [38-40] and the painful shoulder [41,42].

In addition, some studies suggest the same effectiveness of local anesthetics in the therapeutic management of the painful shoulder, if compared with cortisone in subacromial infiltration [43,44], or greater effectiveness when compared with saline in the suprascapular nerve block [45].

Materials and Methods

From 1982 to 31/8/2007, 275 consecutive cases of painful shoulder were treated by the authors at an Outpatient Pain Therapy Center (58/b Dante Alighieri Avenue, Riva del Garda, Trento, Italy). Informed consent has been obtained from all patients. Patient data have been collected by one of the Authors (BP) in a Microsoft Works database, from which they were drawn out and analyzed for this study. Any acute or chronic benign pain condition, originated from shoulder structures (tendinitis, rotator cuff tears, bursitis, capsulitis), has been considered as “painful shoulder”. “Case” means any therapeutic cycle performed for each shoulder, even on the same patient. Of these 275 cases, 47 were treated with acupuncture and 228 with neural therapy. Frequently used acupuncture points: LI 4 (Shangyang), LI 10 (Shousanli), LI 11 (Quchi), LI 14 (Binao), LI 15 (Jianyu), TE 5 (Waiguan), TE 14 (Jianliao), TE 15 (Tianliao), SI 3 (Houxi), SI 9 (Jianzhen), SI 10 (Naoshu), SI 11 (Tianzong), LU 2 (Yunmen), LU 3 (Tianfu), GB 20 (Fengchi), GB 21 (Jianjing), GB 34 (Yanglingquan), BL 10 (Tianzhu), GV 14 (Dazhui), ST 36 (Zusanli). The anaesthetic used was lidocaine 0.5%, in the amount of 0.5-1cc for each wheal or intramuscular injection. The main techniques used were wheals and/or intramuscular injections in the mentioned acupuncture points and/or tender/trigger points in the aching area and/or in areas of metameric interest of the cervical area or of the arm. In the most refractory cases, the block of suprascapular nerve and of the intra-articular of the shoulder have been used more rarely. The aforementioned “interference field” was not considered nor treated. The analgesic result has been represented as the Percentage of subjective improvement of pain (SPRP = Subjective Pain Relief Percentage) at the end of the treatment cycle and at intervals of 6 months for a follow-up of 4 years; and as TAPR≥2y, consisting of the Time of average persistence of the result in subjects with positive results and at least for 2 years of follow-up [46]. Finally, both groups’ data have been compared by Student t-test for independent samples.

Results

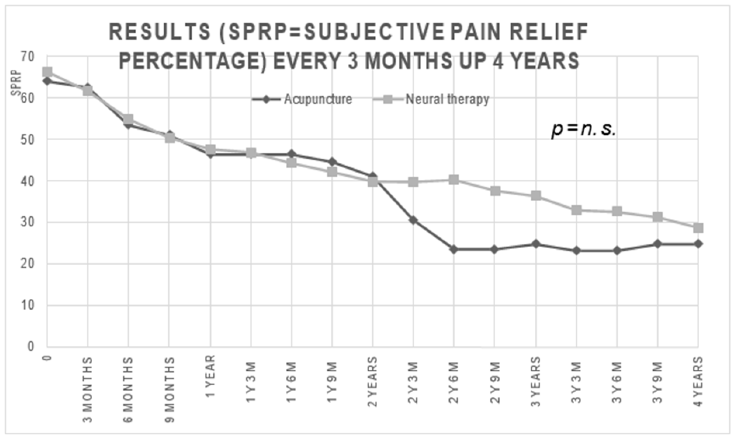

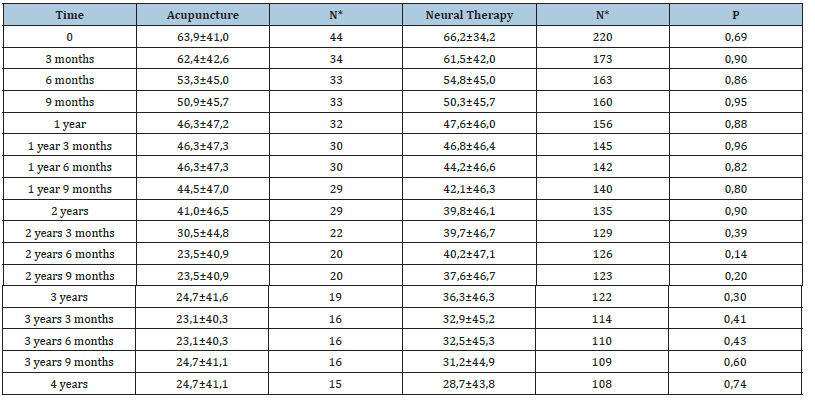

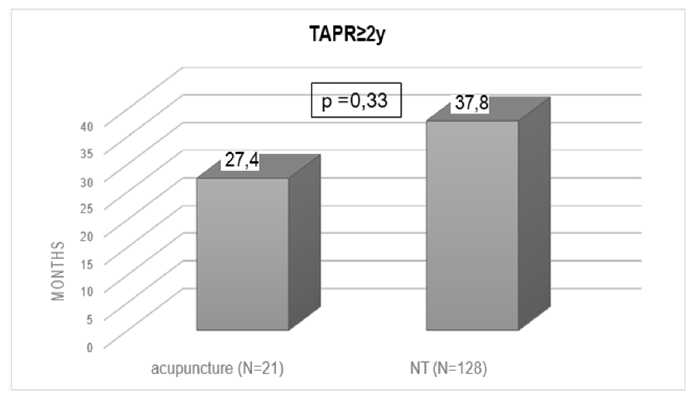

Withdrawn patients, after 1-2 sessions, were 3 (6.4%) in the “acupuncture” group and 8 (3.5%) in the “NT” group (p = n.s.). The two groups left were then examined: group 1 treated with acupuncture (N=44; males = 13 (29.5%)-females=31 (70.5%) and group 2 treated with neural therapy (N=220; males=63 (28.6%)-females=157 (71% ), aged respectively 52.5±16.9 years (range 15-82) and 63.3±14.5 years (range 21 - 95) (p < 0.001), with pain duration of 1 year and 4 months (15.7 months ±36.7 ) (range 0.06 -180 months) and 1 year and 8 months (20.5 months±44) (range 0.03-288 months) (p=n.s.), number of sessions made: 6.5±3.5 (range 1-12) and 6.5±3.6 (range 1-22) (p=n.s.), and duration of the treatment cycle: 30.9± and 25.4 days (range 1-94) and 26.2±21.5 days (range 1-130) (p=n.s.). The analgesic result (Figure 1 & Table1), at the end of the session cycle, was an average percentage of pain improvement (SPRP= subjective pain relief percentage) of 63.9% and 66.2% (p=n.s.). After 6 months, the average percentage of pain improvement was 53.3% (N = 33) and 54.8% (N=163) (p=n.s.); after 1 year, 46.2% (N=32) and 47.6% (N=156) (p=n.s.); after 1 year and 6 months, 46.3% (N=30) and 44.2% (N=142) (p=n.s.); after 2 years, 41% (N=29) and 39.8% (N=135) (p=n.s.); after 2 years and 6 months, 23.5% (N=20) and 40.2% (N=124) (p=n.s.); after 3 years, 24.7% (N=19) and 36.3% (N=110) (p<0.01); after 3 years and 6 months, 23.1% (N= 16) and 32,5,3% (N=110 ) (p=n.s.); after 4 years, 24.7% (N=15) and 28.7% (N=108) (p=n.s.). The Time of average persistence of the result in the cases with a positive result and with follow-up over two years (TAPR≥2y) was 27.4 months ±28.2 (N=21) in group 1, and 37.8 months ±46.8 (N=128) in group 2 (p=n.s.) (Figure 2). In addition, any accidents, complications and side effects using the two techniques have not been observed in both groups.

Figure 1:Immediate and long-term (4 years) analgesic results (Subjective Pain Relief Percentage=SPRP) in the groups “acupuncture” and “neural therapy” (n.s.=Not Significant).

Table 1:Results as “Subjective Pain Relief Percentage” (SPRP) every three months up 4 years

*N=number of patients.

Figure 2:Time of average persistence of result with at least 2 years of follow-up (TAPR≥2y) in the groups “acupuncture” and “NT”=Neural Therapy).

Discussion

This is a retrospective study, so it does not consider any control group, also for the practical difficulty of creating a group of patients not treated or on the waiting list for a private outpatient center as the Author-s one. Therefore, we decided to compare the results obtained by neural therapy, a therapeutic technique practiced a lot in the German and Spanish-speaking countries, but with few specific studies on shoulder pains, and no randomized controlled trials, with those obtained in a smaller control group treated by the same Authors by Chinese acupuncture, a similar technique, in particular in the choice of the points to be treated. The Chinese acupuncture in fact is a therapeutic technique certainly more studied on shoulder pains [25-32], also with randomized controlled trials [27-29], and probably effective, even if not conclusively [15]. At the end of the treatment cycle (immediate result) and up to two years of follow-up, the analgesic result, for both the considered methods of therapy appear similar, while in the following two years the results with neural therapy are better, although this difference is not statistically significant, especially for the narrowness of the group treated with acupuncture. When it comes to the other index of analgesic effectiveness, the Time of average persistence of result (TAPR≥2y), it has been detected much better in the neural therapy group. In this group, the positive results lasted about 3 years vs the 2 years of the acupuncture group. Also, in this case the narrowness of the acupuncture group (N=21) has not allowed the detection of a statistically significant difference.

However, it must be considered that, the number of the sessions, the duration of the therapy and the duration of pain were equal in the two groups, but the neural therapy group was older than the acupuncture group (63 years vs. 52; p<0,001). Being age a negative factor for analgesic outcomes in prognostic terms [47], this data must be regarded as an additional advantage to ascribe to neural therapy, which therefore, in our opinion should be considered superior to acupuncture, in terms of analgesic outcome. Desipte in literature severe complications due to the two described techniques are reported, in particular concerning neural therapy, when particularly invasive like in some anaesthetic blocks of deep structures [48,49], in this study complications have not been reported, also because of the use of minimally invasive neural therapy techniques, essentially subcutaneous wheals and/ or intramuscular of trigger/tender points. The two reflexology techniques discussed here were, in this study, easy-to-perform, harmless, and low-cost, all features that, together with the potential effectiveness, candidate them to be considered as valid therapeutic options of choice for the outpatient’s context. Finally, it must be considered, that in literature there are no other studies comparing acupuncture and neural therapy in the treatment of the painful shoulder. Similar retrospective comparative studies by the same authors, in benign lumbago [50], cervicalgia [51] and headaches [52], are in favour of a slight superiority of neural therapy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the analgesic results were almost always (13 times out of 18) better for the neural therapy group, even though they do not show as statistically different, probably due to the small number of cases treated with acupuncture. Furthermore, there is an additional advantage for the neural therapy: the cases treated with this method were older, a negative factor in prognostic terms. This study represents the first attempt to compare the analgesic results of two widely used but still not much studied methods, in particular neural therapy by Huneke, for the treatment of periarticular pain of the shoulder. Anyway, the results obtained with the two methods are promising and such as to include the methods, among the therapies of choice in case of shoulder pain also for their safety and low cost However, further studies are deemed necessary, in particular prospective and randomized trials with control group, to define the real effectiveness of the two methods, and to determine which of the two is the best one.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PB and FC participated in the design of the study, performed acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. RB participated in the acquisition of data and VG contributed to the drafting and translation of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Kidd BL, Jawad A (2004) Chronic joint pain. Shoulder: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. In: Jensen TS, Wilson PR, Rice ASC (Eds.), Clinical Treatment of Chronic Pain. CIC Editions International, Rome, Italy, pp. 507-508.

- Van der Heijden GJ (1999) Shoulder disorders: A state of the art review. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumato 13(2): 287-309.

- Bamji AN, Erhart CC, Price TR, Williams PL (1996) The painful shoulder: can consultants agree? Br J Rheumatol 35(11): 1172-1174.

- Neer CS (1972) Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 54(1): 41-50.

- Ehrmann FD, Shrier I, Rossignol M, Abenhaim L (2002) Risk factors for the development of neck and upper limb pain in adolescents. Spine 27(5): 523-528.

- Miranda H, Juntura EV, Martikainen R, Takala EP, Riihimaki H (2001) A prospective study of work related factors and physical exercise as predictors of shoulder pain. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58(8): 528-534.

- Devereux JJ, Vlachonikolis IG, Buckle PW (2002) Epidemiological study to investigate potential interaction between physical and psychosocial factors at work that may increase the risk of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorder of the neck and upper limb. Occup Environ Med 59(4): 269-277.

- Andersen JH, Kaergaard A, Frost P, Thomsen JF, Bonde JP, et al. (2002) Physical, psychosocial, and individual risk factors for neck/shoulder pain with pressure tenderness in the muscles among workers performing monotonous, repetitive work. Spine 27(6): 660-667.

- Miranda H, Punnett L, Juntura EV, Heliövaara M, Knekt P (2008) Physical work and chronic shoulder disorder. Results of a prospective population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 67(2): 218-223.

- Macfarlane GJ, Hunt IM, Silman AJ (1998) Predictors of chronic shoulder pain: a population based prospective study. J Rheumatol 25(8): 1612-1615.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Glazier R, Forbes A (1998) Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions for painful shoulder: selection criteria, outcome assessment, and efficacy. BMJ 316(7128): 354-360.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Glazier R, Forbes A (2007) Withdrawn: Interventions for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(4): CD001156.

- Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM (2003) Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(1): CD004016.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick S (2003) Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(2): CD004258.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick SE (2005) Acupuncture for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): 1-3.

- Armstrong A (2014) Evaluation and management of adult shoulder pain: a focus on rotator cuff disorders, acromioclavicular joint arthritis, and glenohumeral arthritis. Med Clin North Am 98(4): 755-775.

- Greenberg DL (2014) Evaluation and treatment of shoulder pain. Med Clin North Am 98(3): 487-504.

- Allais GB, Giovanardi CM, Pulcri P, Quirico PE, Romoli M, et al. (2000) Acupuncture: clinical and experimental evidence-legislative aspects and diffusion in Italy. Ambrosian Publishing House, Milano, Italy.

- Baldry PE (1989) Acupuncture, Trigger Points and Musculoskeletal Pain. Edinburgh London Melbourne New York, Churchill Livingstone, UK.

- Dosch P (1995) Textbook of neural therapy according to Huneke. Therapy with local anesthetics. 4th (edn), Haug Verlag, Heidelberg,

- Barop H (2003) Manual and Atlas of Neural Therapy according to Huneke. Ermes (Ed.), Milan,Italy.

- Weinschenk S (2010) Manual of neural therapy. Diagnosis and therapy with local anesthetics. Munich, Urban & Fischer, Germany.

- Fischer L (2014) Neural Therapy. Neurophysiology, injection technique and therapy suggestions. 4th (edn), Stuttgart, Haug Verlag, Germany.

- Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, et al. (2012) Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 172(19): 1444-1453.

- Jiang D, Liu W (1991) Thick needle treatment for periomitis. J Tradit Chin Med 11: 112-114.

- Wang W, Yin X, He Y, Wei J, Wang J, et al. (1990) Treatment of periarthritis of the shoulder with acupuncture at the zhongping (foot) extrapoint in 345 cases. J Tradit Chin Med 10(3): 209-212.

- Laixi J, Haijun W, Yuxia C, Ping Y, Xiaofei J, Peirui N, et al. (2015) Sharp-hook acupuncture (feng gou zhen) for patients with periarthritis of shoulder: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 312309.

- Garrido JCR, Vas J, Lopez DR (2016) Acupuncture treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 25: 92-7.

- Molsberger AF, Schneider T, Gotthardt H, Drabik A (2010) German randomized acupuncture trial for chronic shoulder pain (GRASP)-A pragmatic, controlled, patient-blinded, multi-centre trial in an outpatient care environment. Pain 151(1): 146-154.

- Lee JA, Park SW, Hwang PW, Lim SM, Kook S, et al. (2012) Acupuncture for shoulder pain after stroke: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med 18(9): 818-823.

- Lathia, AT, Jung SM, Chen LX (2009) Efficacy of acupuncture as a treatment for chronic shoulder pain. J Altern Complement Med 15(6): 613-618.

- Vas J, Ortega C, Olmo V, Fernandez FP, Hernandez L, et al. (2008) Single-point acupuncture and physiotherapy for the treatment of painful shoulder: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47(6): 887-893.

- Challapalli V, Lukats IWT, McNicol , Lau J, Carr DB (2019) Systemic administration of local anesthetic agents to relieve neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019(10):

- Mohammadkarimi N, Jafari M, Mellat A, Kazemi E, Shirali A (2014) Evaluation of efficacy of intra-nasal lidocaine for headache relief in patients refer to emergency department. J Res Med Sci 19: 331-335.

- Kanai A, Suzuki A, Kobayashi M, Hoka S (2006) Intranasal lidocaine 8% spray for second-division trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Anaesth 97(4): 559-563.

- Travell J (1949) Basis for the multiple uses of local block of somatic trigger areas (procaine infiltration and ethyl chloride spray). Miss Valley Med J 71: 13-22.

- Alvarez DJ, Rockwell PG (2002) Trigger points: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 65(4): 653-660.

- Barbagli P, Bollettin R (1998) Treatment of joint and periarticular pain of the knee with local anesthetics (neural therapy according to Huneke). Short and long-distance results. Minerva Anestesiol 64: 35-43.

- Michels T, Ahmadi S, Michels D (2011) Physiological-anatomical aspects in neural therapy: treatment outcomes of acute and chronic pain. German Stucher P Acupuncture 54: 6-9.

- Egli S, Pfister M, Ludin SM, Puente de la Vega K, Busato A, Fischer L (2015) Long-term results of therapeutic local anesthesia (neural therapy) in 280 referred refractory chronic pain patients. BMC Complement Altern Med 15: 200-211.

- Salgado TC, Kings E, Vazquez VE, Thief GMJ (2006) Neural Therapy in Painful Shoulder of Different Etiology. International Meeting of Neural Therapy, Holguin, Cuba.

- Ortner W, Szklanski KG (2012) Shoulder pain - what to do? Neural therapy helps. Complementary Medicine 1.

- Vecchio PC, Hazleman BL, King RH (1993) A double-blind trial comparing subacromial methilprednisolone and lignocaine in acute rotator cuff tendinitis. Br J Rheumatol 32(8): 743-745.

- Alvarez CM, Litchfie R, Jackowski D, Griffin S, Kirkley A (2005) A prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing subacromial injection of betamethasone and xylocaine to xylocaine alone in chronic rotator cuff tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 33(2): 255-262.

- Dahan TH, Fortin L, Pelletier M, Petit M, Vadeboncoeur R, et al. (2000) Double blind randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of bupivacaine suprascapular nerve blocks in frozen shoulder. J Rheumatol 27(6): 1464-1469.

- Barbagli P, Bollettin R (1995) Evaluation of results in pain therapy. Pathos 2: 188-195.

- Barbagli P, Bollettin R (2002) Is ageing a prognostic factor of acupuncture in benign low back pain? In: Ceccherelli F (Ed.), Scientific acupuncture in the third millennium. Padua: AIRAS, Italy, p. 26.

- Wu J, Hu Y, Zhu Y, Yin P, Litscher G, et al. (2015) Systematic Review of Adverse Effects: A Further Step towards Modernization of Acupuncture in China. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015: 432467.

- Heyll U, Ziegenhagen DJ (2000) Subarachnoid hemorrhage as life-threatening complication of neural therapy. Case report. Versicherungsmedizin 52(1): 33-36.

- Barbagli P, Bollettin R, Ceccherelli F (2003) Acupuncture (dry needle) versus neural therapy (local anesthesia) in the treatment of benign back pain. Immediate and long-term results. Minerva Med 94: 17-25.

- Barbagli P, Bollettin R (1998) Comparison of two reflexotherapy techniques (dry needle-local anesthetic) in benign neck pain: preliminary data. G Ital Riflessot Acupuncture 10: p. 41.

- Barbagli P, Bollettin R (2011) Dry needle vs neural therapy in the treatment of headaches: a retrospective study with a 4-year follow-up. In: Allais GB, Bazzoni G, Betti P, Ceccherelli F, Losio A, et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the XXVI SIRAA National Congress : Acupuncture in headaches and neck and facial pain. Florence: SIRAA, Italy, pp. 8-25.

© 2023 Paolo Barbaglie. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)