- Submissions

Full Text

Advances in Complementary & Alternative medicine

Traditional Maori lense applied to Sterilization science: Sterilization of Traditional Reusable Medical Device. Pounamu and the Cutting of Iho, The Umbilical Cord (Funiculus Umbilicalis)

Alison Stewart1,2, Tracey Kereopa2,3 and Campbell Macgregor1,4,5*

1Faculty of Health Education and Environment, Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology, New Zealand

2New Zealand Sterile Sciences Association - executive member

3Central sterile services department, Wairarapa District Health Board, New Zealand.

4School of Health and Medical Science, Central Queensland University, Australia

5School of Graduate Research, Central Queensland University, Australia

*Corresponding author:Campbell Macgregor, Faculty of Health Education and Environment, Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology, Tauranga, New Zealand

Submission: July 14, 2021;Published: July 23, 2021

ISSN: 2637-7802 Volume 6 Issue 4

Abstract

Background: Traditionally, in New Zealand (NZ) and around the world, locally sourced materials have been used to solve local issues. In NZ, stone, bone or shells have been used as cutting tools with one traditional use has been to cut an umbilical cord. Pounamu is beautiful stone, significant to Māori as it links heaven and earth, the stars and water. Pounamu reuse cutting different umbilical cords at birth, must be made medically and culturally safe.

Methods: Two pieces of contaminated and recently used pounamu were selected to undergo full steam sterilization in accordance with the Australian/New Zealand standards. Findings - After the steam sterilization process, neither piece of pounamu showed any growth on any of the blood agar plates after 5 days.

Interpretation: Biologically, the environment where midwifery reusable instruments or customary implements have to be reprocessed to remove all soiling and sterilized. Full steam sterilization process was effective at removing viable microbes. Culturally, water is used traditionally to clean pounamu, placing in a non-traditional autoclave leads to several questions that the community needs to ask and answer. One is, how is the mauri of the cord cutting process affected when the pounamu is sterilized in a steam machine?

Keywords: Pounamu; Traditional practices; Sterilization; Culturally safe; Umbilical cord; Iho

Introduction

Traditionally, in New Zealand (NZ) and around the world, locally sourced materials have been used to solve local issues. For example, in NZ this has included using flax to create fishing nets, and animal hides and feathers to make clothes. Furthermore, stone, bone or shells have been used as cutting tools [1]. These tools have been used for a variety of tasks; one traditional use has been to cut an umbilical cord after the birth of a baby. Pounamu (nephrite jade/greenstone) is a hard, beautiful stone found in the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand, which has been used for this purpose.

Pounamu is significant to Māori and all New Zealanders. It links heaven and earth, the stars and water. It is passed through (families) as an heirloom which maintains connections with heritage and history through the generations [2,3]. The west coast of the South Island is known by Māori as Te Wai Pounamu - the greenstone waters. Pounamu has principally been found in and near the Taramakau and Arahura rivers in Westland,

Milford Sound in Fiordland and Lake Wakatipu in Otago. Legends

tell the story of pounamu. One describes the love of Poutini for

Waitaiki, a married woman, whom he kidnapped. Waitaiki’s

husband pursued them. Poutini turned Waitaiki into pounamu,

his essence, and laid her in the riverbed of a stream (now named

Waitaiki) where it joined the Arahura river. Pounamu can hold the

‘essence of things’. It is able to be cleaned and endowed spiritually

with a purpose. It can protect and support the mana of the person

who holds it. If it leaves the holder, it is thought that it will reappear

in another time and place when ready [3].

This study investigated how traditional use of pounamu for

cutting the umbilical cord at birth, can be achieved in a medically

and culturally safe way, that supported and acknowledged the

mana of pounamu and whānau (family).

The authors wish to acknowledge the time and effort the

midwives referenced in this article to supply key advice and

information to inform this article. Furthermore, several master

pounamu carvers have also provided key referenced information

to allow for safe reprocessing of pounamu. Lastly, several Ngai Tahu

members have also added their knowledge and provided guidance

to the traditional care and beliefs behind the use of pounamu.

Traditional knowledge and Treaty based practice

The Treaty of Waitangi governs the relationship between Māori,

the tangata whenua (indigenous people) of New Zealand and others

who call Aotearoa home. The Treaty protects the rights of both

Māori and Pakeha (European New Zealanders) and by extension,

New Zealanders of other ethnicities, who have arrived since the

Treaty of Waitangi was signed. The Treaty is the foundation on

which the nation has been built and guarantees the following: that

Māori are able to manage their resources, maintain their traditions

and to determine their own organisational structures [4]. Further,

the Treaty requires the New Zealand government to conduct

all interactions with Māori in good faith and “act reasonably”.

Therefore, the Government addresses grievances under the Treaty

and treats all New Zealanders as “equal under the law” (n.p.).

Fokunang C [5] describes traditional medicine as “health

practices, approaches, knowledge and beliefs incorporating plant,

animal and mineral based medicines, spiritual therapies, manual

techniques and exercises, applied singularly or in combination, to

treat, diagnose and prevent illnesses or maintain well-being”. The

traditional use of taonga (pounamu) in contemporary childbirth

settings relates to this Treaty right. Reuptake of such traditional

practices is now more common among indigenous people,

especially in medicine. Thus, they can be empowered and can assert

more control, as provided for under the principles of the Treaty of

Waitangi [6]. The use of traditional practices for Māori whānau

can increase their comfort with and connection to the healthcare

system.

However, it can be challenging to use these practices in the light

of modern medical requirements and to develop understanding,

particularly when things ‘go wrong’. Yet a space and opportunity

exist to investigate how emerging sterilization practice may

intersect with traditional practice, from a treaty-based perspective.

This case study creates a recommended framework or process

to guide indigenous practices which may require a different

approach to complementary or conventional medicine. In this case

study, instead of tying and cutting the umbilical cord with a plastic

clip and scissors, flax and pounamu are used.

Method

To undertake this case study, we acknowledge that the Te Tiriti

o Waitangi allows us the space to have this discussion. Secondly,

we acknowledge that in Aotearoa, the guardians of pounamu are

Ngai Tahu, and finally, that the cultural and medical safety of pepi

(children/babies), whaea (mothers) and whānau underpin our

questions. We recognise that this case study has several limitations.

Firstly, we only performed laboratory tests on one complete

pounamu setup. Secondly, we are not midwives, although we have

asked for midwives’ opinions. There will be an opportunity to

further explore midwives’ views. Lastly, Maori need the space to be

Maori. In this case, it appears that we were able to merge traditional

and current practices, to preserve cultural and medical safety.

Nonetheless, in future case studies, reusable medical devices and

medical processes and procedures might be used in a similar way,

but with a very different outcome. Finally, this article is not ‘telling

Maori how to be Maori’, nor is it commenting on the appropriateness

of using pounamu to cut an umbilical cord, or on whether non-

Māori might use pounamu for this purpose. Rather, the article

aims to provide guidance to enable culturally and biologically safe

practices for whānau who cut the aho with pounamu.

The whakapapa of the iho (umbilical cord) is usually indicated

by one continuous line as in kōwhaiwhai patterns. The central line,

underpinned by symmetrical patterns, is likened to an umbilical

cord, which links whakapapa to the creation of life, a sequence from

Te Kore to Te Po and then to Te Ao Marama [7]. Then the authors

further noted that delayed cord clamping increases infants’ iron

stores.

Case Study Questions

Pounamu - what is it and why is it used?

Ngai Tahu, in the South Island, the custodians of pounamu,

manage pounamu resources through a management plan, to protect

remaining reserves. The origin, whakapapa and carver of each Ngai

Tahu pounamu article can be traced on the ‘Authentic Greenstone’

website [8]. The stone for these items came from New Zealand’s

South Island, has been ethically obtained and treated respectfully.

Gibbs [9] noted that pounamu was treasured as the hardest

stone found in Aotearoa/New Zealand and was therefore a precious

resource for tool making. Best [2] recognised the utility of pounamu

for tool making, as it is harder than steel: “According to Moh’s scale,

steel stands at 6 and nephrite at 6½, hence the latter just escapes

being scratched by steel. In the same scale quartz stands at 7,

topaz at 8, corundum at 9, and diamond at 10.” (Mohs, as cited in (Best, 1912) p.177). He emphasised how valued “nephrite” was.

Firstly, this was due to its “toughness and hardness... no other

stone obtainable by them would carry so keen and thin an edge.”

Pounamu was also highly valued because of its beauty and was

therefore used for ornaments as well as for tools and weapons.

“Such weapons and ornaments were of great value among the

natives. They were in many cases heirlooms, handed down from

one generation to another, and in many cases had special names

assigned to them. They were also, when old specimens, termed and

treated as oha, or loved relics, keepsakes, or mementos of tribal

elders and progenitors long gone to the underworld” (Best, 1912 p.

183). Best also reported that, although it is found in the South Island

only, the stone was most likely traded with North Island tribes, or

obtained in other ways, as it was so highly prized. Pounamu was

additionally used in events such as funerals and to build alliances

between groups [9].

How was it used in the cutting of the umbilical cord over time?

Kelly Tikao - registered nurse and Kairangahau Māori - completing her PhD on Ngāi Tahu birthing traditions assumes that pounamu was used by Ngāi Tahu for cord cutting due to its ready availability (personal communication, October 15, 2019). It was also used to provide relief for pēpi during teething. Kelly explains that traditional cord cutting with pounamu was a clean process, where hands and equipment were clean and dry. Water would have been used to clean the tool after use, and possibly harakeke juice or other rongoā antiseptics, although she has found no specific evidence of this in oral or written accounts. Kelly has found no recorded instances of cord sepsis due to infected equipment and believes that various mordants/poultices of rongoā and muka may have been used. For wāhine Maori in te ao tawhito, the most significant issue was full removal of the whenua (placenta); “retained placenta created infection and could and did lead to death”.

What are the best practices or traditions for looking after the Pounamu?

As mentioned, Ngāi Tahu are the kaitiaki of all South Island

greenstone, the only known source of authentic New Zealand

pounamu. The stone is highly significant to Ngai Tahu and is linked

strongly to the identity of all Māori, and to the identity of Aotearoa

New Zealand as a whole. Sustainable management of the stone is

taken very seriously, along with, advocacy and protection for it, the

rivers it comes from and the carvers and their communities. The

importance of the stone to the greater identity of Māori cannot be

undervalued.

MŌ TĀTOU, Ā, MŌ KĀ URI, Ā MURI AKE NEI: For us, and our

children after us. Pounamu is regarded as a taonga by Māori, many

of whom have a strong spiritual connection to the stone. They wear

it with a sense of pride, and they believe it bestows strength upon

them. For hundreds of years, it has been imbued with legend and

stories; and in many families, treasured pieces have been passed

down through several generations [8].

According to Stacy Gordine, when a master carver chooses

pounamu for ripi (blades), they aim to select fault free, high quality

pounamu (S. Gordine, personal communication, November 6,

2019). Furthermore, they choose pounamu with no soft areas, so,

as measured by Moh’s scale, it will be harder than steel [2]. This

renders the stone easier to shape into a blade and means it will

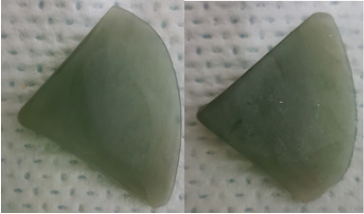

hold a keen edge (S. Gordine). Figures 1 & 2 show two views of a

functional design created by Stacy, which fulfils the tool’s purpose

of cutting the cord, while being comfortable for the user. It is

aesthetically pleasing, with cultural references.

Figure 1:Pounamu - View 1 (Gordine, 2019).

Figure 2:Pounamu - View 2 (Gordine, 2019).

What other practices have been used in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Midwife Kelly has observed the use of kūtai and pipi shells for severing of the aho, in the north, where it is common practice. The cutting took place once the cord had stopped pulsating and was clean. The shells used were reserved solely for this purpose and used for nothing else. They were often placed apart from other domestic tools. According to Kelly, the midwives or tapuhi/kaiwhakawhānau would have maripi (knives made from various resources) amongst their kete rauemi. Muka and kiekie cords could be used to cut, as well as tie. Sometimes tūhua (obsidian shards) could be used and some hapū in the North definitely used their teeth, most likely if women were isolated and had no tools, others would have bitten the cord to sever it from the whenua (placenta).

Is this taonga (treasure) classed as a reusable medical device?

If a pounamu used for cutting the iho (cord) at birth is to be reused for other births, rather than being left with the whānau, it needs to be treated as a reusable medical device [10]. Therefore, it should be reprocessed and sterilized appropriately, and remain sterile until the next use. Cleaning with water, and then using steam to sterilize the taonga, was thought by researchers to be the closest method to the traditional use of water to clean the maripi.

Current Practices

Tawere Trinder, midwife, points out that Māori, who are

required to navigate a Pakeha world, are “constantly compromising

their culture to fit”. This has led to the loss of traditional knowledge

and practices over time (T. Trinder, personal communication,

October 30, 2019). Providing traditional birthing practices in a

contemporary birth setting such as a hospital acknowledges the

importance of Maoritanga (their identity as Maori), for whānau,

regardless of their level of traditional knowledge. Tawera Trinder

is “supportive of midwives, Māori and non-Māori, and whānau

who feel comfortable” to investigate the use of “natural maripi to

cut their babies cords using a clean technique, once the cord has

finished pulsating.” She further explains that, as there are too few

Māori midwives to meet the needs of whānau Māori, non-Māori

midwives are learning traditional birthing practices in order to

provide a much-needed service for Māori. These midwives are:

“advocates and champions” of traditional knowledge.

Tawera describes how traditional birthing practices are taught

through Hāpu Wānanga Taranaki (a Kaupapa Maori childbirth

education programme). This involves teaching whānau how to

use traditional cutting tools including sharpened pounamu and

other tools likely to have been used due to their abundance in a

rohe (area). For coastal Māori this would have included sharpened

kutai shells and other shells and for Māori inland, carved stone, for

example, tuhua (obsidian) or pakohe (argilite) [11].

What is currently being done?

Natural childbirth, in medical terms, is seen as a clean process. However, any items used during the birthing process are required to be sterile at time of use to ensure the risk of infection for the mother and child is kept to the lowest level possible in a non-surgical environment. Devices required are for cutting and clamping the umbilical cord and any used for interventions following the birth [10]. These devices are either reusable instruments, reprocessed and sterilized at a central sterile services department within a hospital or commercially sterilized single use instruments (used once and either left with the whanau or disposed of correctly).

As discussed, Stacy Gordine and other carvers associated with the care and use of pounamu, use water for cleaning tools. Pounamu to be used is of high quality, without flaws, with a sharp edge and polished to a shine.

What did we do? our recommended pounamu method

1. Receive pounamu, rinsed by midwife under tap, as illustrated in Figure 3 & 4.

Figure 3:Front (a) and Back (b) of the cutting blade that was sterilized.

Figure 4:Front (a) and Back (b) of the cutting plate that was sterilized.

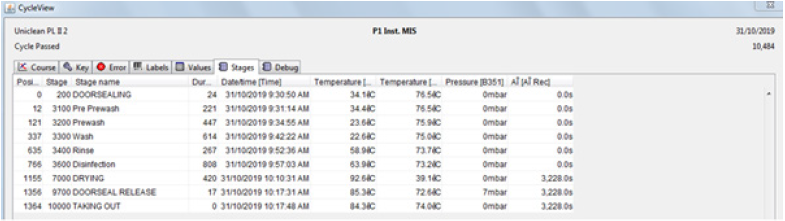

2. Place pieces of pounamu into the washer disinfector by themselves in a DIN tray on a validated instrument load, with one blue GKE cleaning process monitor indicator, for routine monitoring of washer disinfectors. (See attached printout - Figure 5)

Figure 5:Washing cycle printout.

3. Checked computer for washer pass. Passed.

4. Checked GKE for pass. Passed.

5. Removed pounamu from washer disinfector, wearing

sterile gloves and placed into sterile specimen pots (a separate

pot for each piece).

6. Took both pieces of the decontaminated pounamu to

the lab. The microbiology team leader then discussed her

methodology with me as set out below:

a. Re-suspend both pieces of pounamu separately in 30ml of

sterile water. These were then agitated.

b. Pour water off into 2 x 10ml tubes and centrifuge for 20

minutes at 3000rpm (for each piece of pounamu).

c. Decant off the supernatant.

d. Take 0.1ml of the bottom portion of the supernatant and

inoculate 2 x sheep’s blood agar plates per piece of pounamu.

e. Incubate one plate at 30 degrees celsius and the other at

35 degrees celsius for 48 hours, check for organism growth;

incubate a further 5 days and recheck for growth.

7. Laboratory staff returned the pounamu to me after step

6.1.

8. Once again, each pounamu was placed separately in

a DIN tray in the washer disinfector with no pre cleaning,

on a validated instrument load with one blue GKE cleaning

process monitor indicator, for routine monitoring of washer

disinfectors.

9. Check computer for wash pass. Passed.

10. Check GKE for pass. Passed.

11. With clean hands, remove both pieces of pounamu from

the washer disinfector and double pouch together using

Steriking sterile barrier system (pouches) to comply with

EN868-5 and ISO11607-1.

12. Seal pouches using a validated heat sealer.

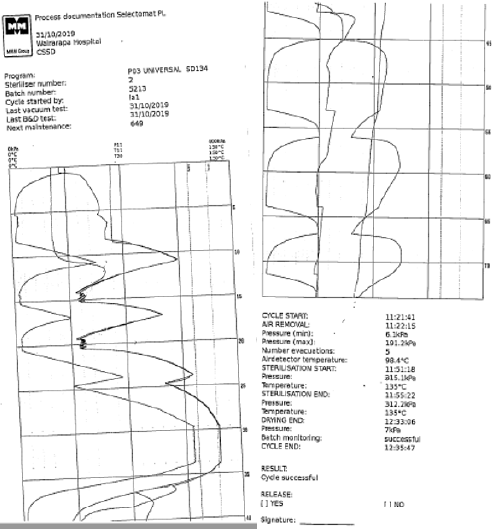

13. Place pounamu on an autoclave trolley (full validated

load) and then in the sterilizer, which was set on a universal

cycle, at 134 degrees celsius, holding for 4 minutes with a 30

minute drying cycle. A GKE PCD (process challenge device) was

included in the load. An example load is depicted in Figure 6.

14. Following the sterilizing cycle, the chemical indicators on

the pouches were observed to have changed, indicating a pass;

the printout also indicated a pass. The PCD also passed. The full

load was released according to hospital procedures.

15. The pounamu was cooled for 3 hours, then returned to the

lab to undergo the process as set out above (6.1 to 6.5).

Figure 6:Pressure and temperature charts of Autoclave from Sterilisation of pounamu.

Results

The decontaminated pounamu in Figure 1 grew one colony forming unit of gram negative presumptive ecoli after 48 hours, on both the 30 degrees celcius and 35 degrees celcius blood agar plates. The decontaminated pounamu in Figure 2 grew 2-gram positive coagulase negative staph (skin) after 48 hours, on both the 30 degrees celcius and 35 degrees celcius blood agar plates. After the steam sterilization process (the complete process) list above, neither piece of pounamu showed any growth on any of the blood agar plates, at 48 hours, 96 hours or after 5 days. Therefore, we can conclude that for these two pieces of pounamu, that steam sterilization was effective.

Discussion

Does the method align with historical practices?

It is not known whether cord cutting tools (maripi) were used and subsequently reused in the pre-colonial era. There was probably variation between rohe (areas), iwi, hapu and whānau, as there is now. Anecdotally, maripi remained associated with the child and were either buried with the placenta or made into a taonga which could be worn. In a Taranaki birth education programme for Māori mothers-to-be, in which Māori midwife Tawera Trinder is involved, women are learning how their predecessors birthed their babies. Hapū Wānanga is run by Māori midwives and is a pilot. Tawera explains that prior to colonisation of Māori, death and infection rates were low. Mothers were mobile while labouring, received miri miri (massage) and were ‘sung to’ [12].

Is the practice culturally safe?

Tawera refers to the fontanel of the pēpi and notes that it is seen as a channel for wisdom and knowledge. Hence tamariki are seen to be wiser than adults. The iho (umbilical cord) is perceived to be a channel for knowledge and wisdom in the same way as the fontanel. Therefore, the cutting of the iho is hugely significant. The question arises: How is the mauri of the cord cutting process affected when the pounamu is sterilized in a steam machine? Does it need to be blessed after each cutting of the iho? Only the Māori community where this wonderful traditional practice is being undertaken can answer the above two questions.

What sterilization processes are required by the Ministry of Health for birthing units?

The Ministry of Health (MOH) does not provide specific

guidance concerning taonga used in relation to childbirth. However,

in 2010, the Ministry published guidelines for customary tattooing.

While tattooing and childbirth may seem unrelated, when

traditional tools are used, a risk of infection to the client is present

in either situation. Tattooing breaks through the sterile barrier of a

person’s skin, which exposes the client to the risk of infection. This

risk is increased if the tattooing instruments are not free of viable

microbes. The guidelines state:

The following basic principles must be observed by tattooists/

tufuga:

i. The premises must be kept clean and hygienic.

ii. Any article used for penetrating the skin must be sterile.

iii. Any article that has penetrated the skin or is contaminated

with blood must be either disposed of immediately, as infectious or

biological waste, or be cleaned and sterilized before being used on

another person [13].

Therefore, the expectation for other practices where taonga

may become contaminated with blood should either be disposed

of or reprocessed and held sterile until next use. The hospital

environment where midwifery instruments are reprocessed

these requirements align with the Ministry of Health. Reusable

instruments or customary implements have to be reprocessed to

remove all soiling and sterilized to ensure the devices are free of all

viable microbes.

What standards cover this?

To support the specified approach to sterilising traditional

cutting tools, Spaulding’s [14] classification of reusable medical

devices should be referred to. The classification describes the

level of processing a reusable device should receive before being

returned for use, based on the intended purpose of the device.

Spaulding’s classification:

i. Critical - these are devices that break the skin and mucosal

layers and come into contact with blood

ii. Semi-critical - these devices make contact with mucosal

layers or are used in natural openings

iii. Non-critical - these devices come into contact with intact

skin surfaces [14].

Standards establish best practice for central sterile services

departments (CSSD) to ensure that reusable devices, including

taonga, are reprocessed correctly and returned to use in the

desired state. The primary standard is AS/NZS 4187 Reprocessing

of reusable medical devices for health service organisations.

Taonga made from natural products such as stone, bone and

shell do not arrive with manufacturer’s instructions. The CSSD is

therefore required to design a process that will enable these and

other special items to be successfully reprocessed. CSSDs are

required to prove their ability to maintain best practice under NZS

8134:3 of the Health and Disability Services (Infection Prevention

and Control) Standards. This standard is mandatory for providers

subject to the Health and Disability Services (Safety) Act 2001.

Hospitals, and CSSDs within them, are subject to this Act.

Recommendations

The standards

Standard AS/NZS 4187 identifies a taonga used for cutting an umbilical cord as a critical device under Spaulding’s classification because of its cutting action which involves contact with blood during the severing of the cord. The cutting carries a risk of infection or transmission of blood borne viruses, if the device has not been reprocessed appropriately. Thus, these cutting instruments have to be exposed to a process that removes all residues and renders them sterile (free of viable microbes). This approach is supported by the Customary Tattooing Guidelines for Operators [15]. An alternative approach is to treat the taonga as a single use item and to gift the item to whānau following use.

Practical implications

Implications for the community

There are barriers to the culturally safe use of traditional tools in the birthing process. This means that all staff who have a role in providing these tools for Maori whānau need to offer them in a genuine, supportive spirit. “Negative responses and begrudging attitudes” to Māori practices surrounding birth, such as the use of cutting tools and cord tying with flax ties can potentially derail any positive progress made in connecting Māori whānau with the health system [16]. This is a well-documented issue for Maori.

Implications for pounamu carvers/master crafters

Avoid soft inclusions or faults on the cutting blade part as it would be difficult to create an even edge. Another thought is that any cracks or inclusions could have the potential to soak in blood and other microorganisms, individuals should be specific and particularly when selecting the uncarved pounamu when creating ripi for the purpose of cutting Iho.

Implications for sterile services departments

Each natural product has a greater or lesser degree of porosity and level of resistance to heat and pressure. Consequently, studies to assess the device for reprocessing would need to be completed for each new device. How realistic is this approach for taonga? The investigation process for one object could take several weeks, as it involves lab testing and the demonstration of reproducibility and repeatability of the investigation. For practical reasons this may not be a viable approach.

Consideration should be given to completing a series of studies on the range of natural products in use, to create guidelines to be used nationally. As a result, CSSDs would have appropriate reprocessing guidelines without needing to complete individual studies. Support from the Ministry of Health and the New Zealand College of Midwives, to enable these guidelines to be developed, would make the use of taonga safe and give whānau a safe choice when planning the delivery of their pēpi.

Implications for mother, baby and whānau

As previously discussed, historically, the taonga used for cord cutting could be associated with the child and be buried with the placenta or made into a taonga which could be worn. In the contemporary context, many Māori whānau are culturally displaced and/or lack the physical or financial access to traditional tools for cord cutting [17]. For example, arranging the carving of a pounamu can be difficult and expensive. Providing whānau with traditional cutting tools which meet medical requirements can help them feel acknowledged and connected as Māori during this special time and can establish the Māori identity of the pēpi. This has a positive impact on the wellbeing of mother, pēpi and whānau, not just on their physical health but mentally and spiritually (non-published post wananga survey responses).

Implications for midwives

From the research undertaken, it appears that steam sterilization using an autoclave according to the procedure outlined in this paper, will be adequate to sterilize pounamu as a reusable medical device. Wherever possible, it is recommended that tools used to cut the umbilical cord are gifted to the family. However, where this is not possible and pounamu are shared among whanau (due to cost), then a sterilization protocol such as the one described in the methods section would be used.

Both Māori and non-Māori midwives have an important role in enhancing the birthing experiences of mothers, pēpi and whānau. Non-Māori midwives who embrace traditional Māori practices alongside their Māori colleagues, help to better connect whānau with the healthcare system through positive experiences surrounding the birth of their pēpi [18].

Conclusion

As stated earlier, this article is not ‘telling Māori how to be Māori’, nor is it commenting on the appropriateness of using pounamu to cut an umbilical cord, or on whether non-Māori can use pounamu for this purpose. The article aims to provide guidance to enable culturally and biologically safe practices for whānau in childbirth, who cut the iho of their pēpi with traditional tools.

The Te Tiriti o Waitangi allowed the space for this investigation and discussion and protects the rights of Māori to be Māori. Therefore, when implementing traditional practices in contemporary birth settings, culturally and biologically appropriate procedures and implementation need to be assured. This will maintain the cultural and biological safety of pēpi (babies) and whaea (mothers) safe. The researchers have three suggestions. If financially possible, pounamu should be considered a gift to the pēpi from the whānau. Secondly, Māori whānau should be educated on the use of non-Pakeha ways of undertaking the cutting of the umbilical cord, allowing them as Māori to be Māori. Finally, if pounamu cord cutting tools are shared among whānau they should be sterilized using heated water in an autoclave to eliminate bacteria, to protecting pēpi, whaea and whānau culturally and biologically.

Traditional Closing

In closing, Pūmotomoto, relates to the process wherein traditional knowledge is played into the pēpi via the fontanel, the channel for esoteric knowledge and wisdom. As explained by Pūmotomoto is the “doorway from the eleventh heaven into the twelfth, the place where the esoteric knowledge was kept, and the place of Io”. Pūmotomoto was guarded by Tūī. The name Pūmotomoto is also given to the instrument that “played into the fontanel of the young” to transfer whakapapa and karakia from the elders to the learner. As mentioned, both the fontanel and the iho (umbilical cord) are channels for this wisdom and knowledge [19]. This gives particular significance to the cutting of the iho. The focus of this article was on how pounamu use can be conducted in a culturally and medically safe manner [20].

While a recommended process to cover the medical safety of traditional use of pounamu for cord cutting has been established by this study, there has also been an acknowledgement of past practices in caring for pounamu. To adopt traditional practices in the modern context, Māori, specifically individual whānau, who are reusing a medical device including a pounamu to cut their baby’s iho, need to ask two questions and be comfortable with the answers: What mauri is transferred, and then, what mauri is transferred or displaced when the pounamu goes through a steam machine?

References

- Coffey PS, Brown SC (2017) Umbilical cord-care practices in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 17(1): 68.

- Best E (1912) The Stone Implements of the Maori. Dominion Museum no. 4. Bulletin, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Pounamu – protecting Aotearoa New Zealand’s precious heritage. New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand.

- Torepe TK, Manning RF (2018) Cultural taxation: The experiences of Māori teachers in the Waitaha (Canterbury) Province of New Zealand and their relevance for similar Australian research. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 47(2): 109-119.

- Fokunang C, Ndikum V, Tabi O, Jiofack R, Ngameni B, et al. (2011) Traditional medicine: past, present and future research and development prospects and integration in the National Health System of Cameroon. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 8(3): 284-295.

- Ministry of Health (2014) Treaty of Waitangi principles. Wellington, New Zealand Government, New Zealand.

- Mercer J, Erickson-Owens D (2006) Delayed cord clamping increases infants' iron stores. Lancet 367(9527): 1956-1958.

- Ngai Tahu Pounamu (2019) Ngai Tahu Pounamu.

- Gibbs M (2003) Indigenous rights to natural resources in Australia and New Zealand: Kereru, Dugong and Pounamu. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 10(3): 138-151.

- Panta G, Richardson AK, Shaw IC (2019) Effectiveness of autoclaving in sterilizing reusable medical devices in healthcare facilities. J Infect Dev Ctries 13(10): 858-864.

- Gardner S (2018) Birth centre adopts traditional Maori practices. Sunlive.

- Groenestein C (2018) Pregnant women learn about traditional Māori birth practices. Taranaki Daily News.

- Sears A, McLean M, Hingston D, Eddie B, Short P, et al. (2012) Cases of cutaneous diphtheria in New Zealand: implications for surveillance and management. N Z Med J 125(1350): 64-71.

- Spaulding EH, Rettger LF (1937) The Fusobacterium genus: I. Biochemical and serological classification. J Bacteriol 34(5): 535-548.

- Connor HD (2019) Whakapapa Back: Mixed Indigenous Māori and Pākehā Genealogy and Heritage in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Genealogy 3(4): 73.

- Tikao KW (2013) Iho-a cord between two worlds: Traditional Māori birthing practices. University of Otago. New Zealand.

- Meegan ME, Conroy RM, Lengeny SO, Renhault K, Nyangole J (2001) Effect on neonatal tetanus mortality after a culturally-based health promotion programme. Lancet 358(9282): 640-641.

- Clarke A (2012) Born to a changing world: Childbirth in nineteenth-century New Zealand, Bridget Williams Books, New Zealand.

- Hata A (2019) He Tātai Whetū ki te Rangi Mau Tonu, Mau Tonu He Tātai Tangata ki te Whenua Ngaro Noa, Ngaro Noa. Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand.

- Schaniel WC (2001) European technology and the New Zealand Maori economy: 1769–1840. The Social Science Journal 38(1): 137-146.

© 2021 Campbell Macgregor. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)