- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

Thinking With Bookworks: The Making and Sharing of Artist’s Books to Generate Relational Networks

Jo Milne*

Eina, University Center for Art and Design, Barcelona, Spain

*Corresponding author: Jo Milne, Eina, University Center for Art and Design,Barcelona, Spain

Submission: October 10, 2022Published: October 31, 2022

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume4 Issue3

Abstract

Collaborative practices are common in the making of artist’s books, in their fabrication and in the genealogies they establish. Artist’s books can foment affective entanglements and foster multiplications, facilitated by their nature as entities working at what Anna Tsing [1] would describe as the ‘unruly edges’ of the art world. The collaborative nature of making and sharing bookwork’s enables diffraction and creates different forms of kinship. Although artists’ books form part of many museum collections my focus here lies on what Magali RABASSA, describes as ‘organic books’, as opposed to commercial books, (2019: 24) and how collaborative bookmaking practices can become “become transformative connections-merging inherited and constructed relations [2]. Where the making, sharing and reading of artists books evidence a form of what María Puig de la Bella casa describes as ‘thinking with’. A thinking where the emphasis is placed “not so much [on] who or what it aims to include and represent…but what it generates; how it actually creates a collective and populates a world. Instead of reinforcing the self of a lone thinker’s figure, …Thinking-with makes the work of thought stronger: it both supports singularity by the situated contingencies it draws upon and fosters contagious potential with its reaching out [3]. This article points to how the fabrication and sharing of bookwork’s can generate relational networks

Keywords: Transmitter; Library; Publishing houses; Public museum

Introduction

The development of artists books involves multiple agencies, from the material to the human, and the collaborative nature of alternative publishing practices, in particular, affords practices of thinking and writing that generate diffraction and multiplicity. Where the publications could be said to work “to make a difference – a diffraction…the ways in which (a) difference is made here do not reside so much in contrasts and contradictions but in prolongations and interdependencies” [4]. I will use a series of examples to point to practices of collaboration across temporalities and social groups, used to fabricate new narratives. They adhere to a writing-with, that as Maria Puig de la Bellicose, proposes is not who or what it aims to include and represent in a text, but what it generates: it actually creates collective, it populates a world. Instead of reinforcing the figure of a lone thinker, the voice in such a text seems to keep saying: I am not the only one. Thinking with makes the work of thought stronger, it supports its singularity and contagious potential. Writing-with is a practical technology that reveals itself as both descriptive (it inscribes) and speculative (it connects). It builds relation and community,” (2012:203). The bookmaking practices considered here operate as practices of making-with, that creating on the one hand, a form of artistic genealogy and on the other, an interactive kinship. As Adrian Johns asserts in The Nature of the Book: ‘any printed book is, as a matter of fact, both the product of one complex set of social and technological processes and also the starting point for another’ (1998:3). But in this article, I wish to highlight how the production of artists books can generate other forms of relational networks. Networks which differ from those traditionally involved within the publication of commercial books (editor, proof-reader, designer, publisher, printer, writer etc.) as they adhere to other forms of production and interaction. To outline these relational networks, I will consider 26 Gasoline Stations (Ruscha, 1963), Enacts (Terrella, 2010) and the wall of books presented by Dulcinea CATA Dora at the MAR (2013) in correlation with other bookwork’s. My conceptualization of these relational processes draws on the assertion of cultural theorist, Johanna Drucker that a future history of the book must “grasp an alternative conception – in which a book is conceived as a distributed object, not a thing, but a set of intersecting events, material conditions, and activities” (2014, 11). Vital to the relational networks established by the artist’s books considered here, is their nature as physical objects, for in bookwork’s both visual and tactile properties resonate in the hand [5]. My focus is therefore on books made with paper, for artist’s books are registers, not just of what they transmit but also how the paper acts as a nexus, documenting the passage of time. Ink fades and paper yellows, holding a “zine from even just ten years ago feels like holding an historical document. It’s easier to place it, the writing inside, and the person who wrote it, in a particular moment in time to contextualize it. Words appearing on a computer screen, even if they are date-stamped seem the opposite” [6]. For paper books mediate the connections not just of “people” but of bodies” [6].

Bookwork’s

There are many denominations used to refer to the book as a work of art, and their resistance to definition has led me to identify them as ‘singular publications’ to evade their pigeonholing in the articulation of the six annual artist’s book fairs organized at EINA, Printed and as ‘resistant transmitters’ [5]. But as my endeavor here is to highlight how artist’s books can be used to undermine traditional commercial practices and generate community, I will adopt the term bookwork’s [7], as it is a hybrid of noun and verb. For I am interested in correlating the development of bookwork’s with what the Hispanic scholar, Magali RABASSA identifies as ‘organic books’ that can function as: “an autonomous object that emerges not from institutional dynamics and structures…but rather from collective practices of experimentation and becoming” (2019:14). Where procedures of fabrication and distribution are used to “disorganize, unsettle, and disorder (disorder)...the social relations and economic principles that underlie commercial, profit-oriented production” [8]. The bookwork’s considered here point to their agency within the multiplication of narratives through affective engagements, across temporalities and peoples. Not all of the books considered in this article were realized by multiple authors, but all I believe work with a form of co-authorship, a form of thinking-with that is more or less implicit. This relational thinking “creates new patterns out of previous multiplicities, intervening by adding layers of meaning rather than merely deconstructing or conforming to ready-made categories” [3]. Where different forms of co-authorship seek “to think with: rather than indicating a method to “unveil” what matters of fact are, … thus not so much a notion that explains the construction of things than it addresses how we participate in their possible becoming” [3]. This thinking with, is correlated by Puig de la Bellicose with a speculative affective mode, operating with “a transformative ethos rather than a normative ethics. … attuned to ways of knowing on the ground, involved with effects and consequences, with an ethicality involved in sociotechnical assemblages in mundane, ordinary, and pragmatic ways” (2017: 67). In the following, I will outline two branches of networks generated through bookwork’s; looking first at how the practices of appropriation and variation are used to generate a form of relational genealogy through a consideration of Ruscha’s 24 Gasoline Stations and then at more socially interactive relations.

Genealogies in Bookwork’s - The Generation of Kinship though Self-Referentiality

The use of recycling, or appropriation of ideas and materials is a common practice within the art world, but in artist’s books appropriation often establish a form of genealogy or co-authorship that works cross temporalities. This recycling of ideas and materials, can take the form of palimpsests, altered books or reinterpretations, but as Sowden [9] suggests, the appropriation of the seminal book Twenty-six gasoline stations by Ed Ruscha is almost a genre in itself. Ruscha’s book sowed the seed for the acceptance of the book as a form of art, while at the same time questioning what a book could be. Instantly recognizable for the simple red typeface of the cover, the book documents the gasoline stations on the route driven by Ruscha. Ruscha was not interested in a hand-made book [10], so much as he wanted the book to act as a consumer-friendly transmitter of his ideas. Consequently, he used cheap commercial printing systems, the low production costs thereby enabling him to distribute his book at 3$ a copy and reach a different audience The multiple appropriations of Ruscha’s book establish a form of genealogy, each reinterpretation generating a new narrative but at the same time establishing an aesthetic kinship. Ruscha is afforded an unstated but fully acknowledged co-authorship. Each iterative transformation diffracts new temporalities and locations in what could become an entangled spacetime mattering [11], a process that continues, with 2022 seeing the publication of Eric Week’s Twentysix Wawa Stores (2022). A similar genealogy can be identified in relation to Stéphane Mallarme Un coup de Das jamais ‘Carolina le Hazard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance), published posthumously in 1897. The work, often seen as a forerunner of artist’s book, used text to evoke images, for Mallarme envisioned the book as a ‘spiritual instrument’, in which different font sizes and types could entangle the reader in multiple pathways. The book already pointed to the possibility of multiple readings, but as with Ruscha’s 26 Gasoline Stations, various artists have since reinterpreted the text. In his Un Coup de Das Marcel Brothers (1969) blocked out the text with black rectangles printed on translucent paper, that enable a reading of the lozenges of movement across but also through the pages, an interpretation echoed in turn by the laser die cut version, by Michalis Pichler (2008), where the blocks are reduced to laser cut holes. While Jeremy Henequin’s Le hazard ‘Carolina jamais un coup de dés (2013) progressively decomposes the book, erasing the text over a period of days, until the contents is reduced to a white page. Each version entangles Mallarme in an aesthetic kinship and diffracts the original text into variant forms. These relations differ from those I identify in the following section, where the focus shifts to the engendering of community interactions rather than aesthetic kinships.

Enacts (Terrella, 2010) and Cartoner Publishing

Enacts (Terrella, 2010) and the wall of books presented by the collective Dulcinea CATA Dora as part of the exhibition O Abrigo e O Terrene (Shelter and Land), although very different in their realization and aesthetic, share a fundamental belief in the role books can play as generators of relations. With this I mean the books generated a network of actants akin to those identified by Bruno Latour [12] in his analysis of scientific laboratory life, where the actants (human and material) and their forms of knowledge and knowhow inform both the fabrication and the distribution. The two projects, operate on what Anna Tsing would call the ‘unruly edges’ [1] for although presented in public galleries they evaded the restrictions of the art market to generate new forms of exchange. Forms of exchange aimed at generating community and knowledge, for in both cases, the bookwork’s were the result of a process of distillation and were presented as gifts. Both, Terrella and Dulcinea CATA Dora sought to use books as catalysts, to change the way we look and read but also to remind us of our entanglement with each other.

Enacts

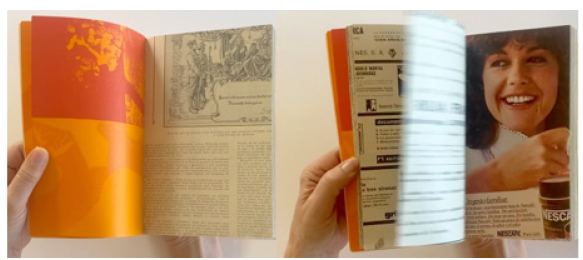

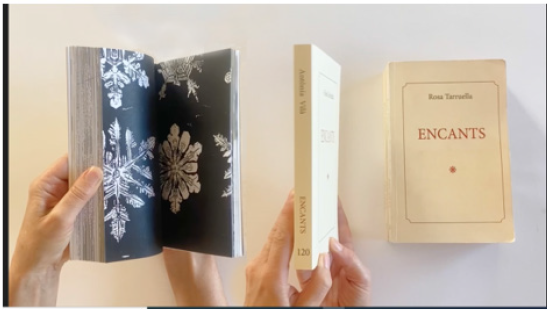

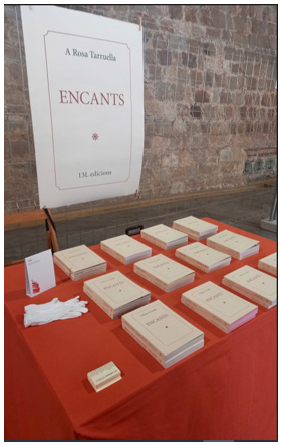

Enacts, developed in 2010 by Rosa Terrella, with the aid of a research grant from the Catalan government, was presented in the Sepia Barra de Ferro in 2011 in the form of a shelf of books (Figure 1). The covers of the books established a kinship with the Gallimard publishing house, by adopting the colour and format of the editorial. The interior, however, presented a random selection of magazine and newspaper cuttings, prints and other types of paper collated into fragmentary narratives (Figure 2). Each page provided a snippet of some aspect of the collections of the artist and her father, brought together in a “cutting together apart” [1]. The discolored magazine pages, and the advertising styles redolent of the forties and seventies point to times past, but also interweave more recent presents, in the form of proofs of Terrella’s etchings. The title plays on the double meaning of the word Enacts (in Catalan the word means charms or enchantments but is also used to refer to a flea market) and this underpins Terrella’s articulation of the book. In referring to the Enacts, the flea market that sits on the Glories roundabout that formed part of Terrella’s daily route, she locates it within Barcelona but also refers to the unexpected delights of foraging. The book exemplifies the unexpected collisions that occur in flea markets, where magazines, textbooks and discarded false teeth can nestle together amidst the remnants of discarded lives. Enacts, recycled the flotsam and jetsam of printed matter accumulated over years into an indexed publication, officially classified by its ISBN number. Terrella, however, undermines the role of this ISBN; visually, by distorting the barcode on its cover (Figure 3) but also conceptually, as each copy identified under the ISBN is different. Each book, although sharing a family resemblance, offers a different collation of printed remnants. Terrella’s play on the role of the ISBN number, resonates with Ruscha’s frustrated attempts to obtain an ISBN number for 26 Gasoline Stations. For though Ruscha sent two separate copies to the US Copyright office and the Library of Congress they were rejected [13]. This rejection established Ruscha’s book as officially unclassifiable, and even though Ruscha turned the rejection letter into a five-inch advertisement on page 55 of the March 1964 issue of Artform, the book was not accepted as part of the Library of Congress collection. Terrella’s turn with the ISBN, is embedded in her interest in questioning the nature of published books, for Enacts was designed to be presented as a unit. In the Sepia Barra de Ferro, the 180 copies were distributed on a single shelf, that emphasized their uniformity (Figure 1). Only the numbered spines pointed to their possible differentiation. Placed within easy reach, visitors were invited to forage and pick a copy. The project was described by the anthropologist, Octave Roofs, as a collation and a propagation. A propagation informed by the act of giving, emphasized by Terrella’s presence at the exhibition. For as Roofs suggests, “that which distinguishes the gift from merchandise is its capacity to generate relations. In merchandise, once closed the transaction, the relation between parts is broken; the gift, on the contrary, opens up a chain of alliances, commitments and debts that maintain active the relation. … [Terrella’s] presence during the donation meant that this was not an anonymous act, impersonal and facilitated proximity and interaction” [14]. Discarded remains became transformed into treasured gifts, a togetherness generated by the gift, but also through the sharing of memories prompted by the fragmentary texts and images. This generation of relations spawned its own aesthetic kinship in the form of the collaborative project, Enacts, Rosa Terrella (henceforth Enacts RT), developed in 2021 by the research group 13L. Where members of the research group, that Rosa Terrella formed part of until her death, developed different responses to Terrella’s book (13L, 2022). In Enacts RT, each member appropriated Terrella’s methodology interweaving references to the birds or flowers that populated Terrella’s work, or through photographs and texts of the artist. As in the original version only the spine indicated the different versions, for the purpose of the project was to generate a form of co-authorship in homage to Terrella’s diffraction of readings. The presentation of Enacts Rosa Terrella at Arts Libris, Barcelona in 2020 (Figure 4) triggered a response, in those who perused them, to reconsider what could be fabricated from the printed flotsam and jetsam of their own lives, entangling the narratives of Rosa Terrella with those of 13L and the public who carried the books away1 (Figure 5).

Figure 1:Exhibition rosa tarruella, encants, espai barra de ferro, 2011.

Figure 2: Rosa tarruella, encants, 2010. Artist’s book, Edition of 180 copies.

Figure 3:Rosa tarruella, encants, 2010. Artist’s book.

Figure 4:13L, Encants, rosa tarruella, 2021, Arts Libris, Barcelona.

Figure 5:13L, Encants rosa tarrarts libris 2021 Encants.

O Abrigo E O Terreno – Dulcinéia Catadora

A similar mechanism of giving was used in the wall of books presented by Dulcinea CATA Dora in the exhibition, O Abrigo e o terrene, that inaugurated the new Museo de Arta de Rio (MAR) in 2013. Unlike Terrella’s shelf, however, the wall offered a diverse array of publications made by the collective Dulcinea CATA Dora. Founded in 2007 by Glycerin, Luis Rosa and three waste pickers, Dulcinea CATA Dora forms part of a network of cartoner publishing houses, whose practices challenge and reconfigure the contexts in which they work. Cartoners distribute handmade books, generally composed of photocopied A4 pages stapled into a hand painted cover made of recycled cardboard, purchased from cardboard collectors, or cartoneros. These publications are often sold at modest prices, with any profits used to facilitate the livelihoods of cartoneros or the cooperative. The publications evidence the locality of their manufacture, in the case of Dulcinea, the cardboard comes from the recycling cooperative Glycerin where the imprint is sited. Whereas in the cartoner, Editorial Retazos2 (Buenos Aires) fabric remnants, or reasons, are used to make the book covers, in recognition of the multiple workshops dedicated to garment fabrication in Buenos Aires. Here, even the shapes of the fabric scraps are respected “in an effort to preserve the presence of the worker who cut it” [15]. Workshops are a key organizational aspect of cartoner publishing and their productions are often based around workshops or Encuentros. The Portuguese word InControl, can be translated as a meeting, gathering, convergence or conference, “a method of networking, while also disseminating and celebrating work, regularly used by cartoners” [16]. Lúcia Rosa, the founder of Dulcinea CATA Dora, highlights the importance of these networks, ‘of course, it’s all about networks’ [17]. Equally Sergio Fong (La Rueda Cartoner;) insisted that “all those who take part in the cartoner movement are interconnected. The network enables us to know, and inform one another, about what’s going on in the cartoner world. It allows us to support one another in a brotherly way” [18]. Composed of a multiplicity of alliances cartoners use bookwork’s as a tool for socio-artistic collectives, their goal, being an ‘affective politics’ [19].

Dulcinéia Catadora at Museo De Arte Do Rio (Mar), Rio De Janeiro

Dulcinea’s installation in MAR, was different, however, in that it was situated within the constraints of the inaugural exhibition of a public museum. Made possible “by a year-long series of face-to-face sessions with residents of the Morro da Providencia” [16], the piece enabled the residents to create their own architectural intervention in the museum, a wall of cartoner books documenting their concerns. The tower of books acted as a monument to the creative vitality of the Morro community, overlooked and endangered by the very process of redevelopment and gentrification epitomized by the MAR museum. The wall reminded the visiting public of the proximity but also, more importantly, the potential of those who lived within the Morro. Among the publications presented in the wall were; Slouches Providencia is, (Providential Solutions) that showed photographs and comments from the group about the improvisations that favela residents develop to resolve housing difficulties; De La par Ce, de Ce par La (From there to here, from here to there) that documented the desires of the young residents to get to know and move through spaces in the city, collated with the group’s dialogues about rights and citizenship, while No’s, Daquin (Us from here) recorded the place threatened by its own disappearance, and the unravelling of the affective ties of about three hundred families. In total, the Morro residents made around 1100 books and the residents received five reals for each booklet assembled. Dulcinea CATA Dora’s monument of books did not succumb to being a static display within the museum, however, so much as the viewer could dismantle it, for the books were presented as gifts. The viewer was invited to discover the narratives generated by the workshops and to take them away, to make them their own, museum staff replenishing the shelves of the wall as they emptied. The reader became an embodied participant, a co-producer of meaning, controlling the pace of the reading (Dulcineiacatadora, 2013). The books acted as seeds, disseminating the voices and concerns of a commonly ostracized community. Unlike Terrella’s project where the diversity of the contents was concealed under the guise of a Gallimard publication, the wall celebrated the multiplicity of the residents’ voices, the colour and diversity of the books becoming for some an invasive presence. But both examples celebrate the multiple narratives generated through a process of thinking with, and both generated regenerations; Enacts leading to Enacts RT, and Dulcinea’s wall to projects in various other localities.

Feminist Fanzines and Networks of Intimacy

The clunky aesthetic and vibrant painted colour of cartoner publishing, that evidences the physical act that goes into their creation resonates with the handmade ethos of many feminist fanzines or Girl zines. Where the maker’s body is made present, through the rough edges left by scissors, or the remnants of tape that resonate in the photocopy into the final copy [20-22]. Generated often within the confines of the home, their very domesticity causes “little eddies of artefacts [to] accrue around girl zines, circulating between readers and creators. Zines instigate intimate, affectionate connections between their creators and readers, not just communities but what I am calling embodied communities, made possible by the materiality of the zine medium” [6]. In these productions, as in Enacts or the cartoner publication, the emphasis is placed on the making and sharing, rather than on commodification. Many zingers admit that fanzines generally cost more to make than they recoup but continue as they delight in establishing relational networks. Gifting also occurs, as in the case of Cindy Crabb who pushed one of her zines into the pocket of an unknown girl, the zine creating community “between two young women who don’t know each other and may not find community otherwise” [6]. Crabb’s gesture described by Piemaker as the creation of a “currency of intimacy”, in which “the tangible object [the book] transforms an imagined relationship into an embodied one” (2009:149).

Conclusion

In an age of electronic media, when the future of the book itself is often called into question, bookwork’s enable subtle subversions, in their ability to materialize relations and ethics of horizontality and autonomy [8]. The importance of such relations is evident, for as Aver Barilaro, a member of the Eloisa Cartoner, states, “Affective relations are at the heart of the cartoner movement, since we’re outside capitalism and all that, we value everything, affective” (Cartoners, YouTube). The sharing implicit in the Encuentros and workshops that underpin the practices of the cartoners, or the gifting of Terrella’s Enacts resonate with the flurry of exchanges that occur at the end of artist’s book fairs [5]. The affective agency of making bookwork’s, the practice of thinking through doing, can “bring people into conversation, provide them with a space to be creative and imperfect, and remove some of the stakes-the dangers of online media, the gate-keepers of mainstream publishing” (Pipi Meier, P. 153.) Organic bookwork’s enable a proliferation of voices to diffract into alternative narratives, acting as nodes of agency for the sharing of knowledge and entangling of communities. For they evidence how thinking with celebrates multiplicity and can create “diffraction”. Where diffraction is seen as a means to multiply, to generate difference rather than a mere “reflection” of sameness [11]. For Cartoner publications, and bookwork’s like Enacts propitiate interactions in which everything participates, everything acts, in an ongoing process of world making. Bookwork’s can offer an alternative to more commercial capitalist modus operandi, and “enact a public pedagogy of hope” [6].

References

- Tsing A (2012) Unruly edges: Mushrooms as companion species: For donna Haraway. Environmental Humanities 1(1): 141-154.

- Haraway D (2003) The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people and significant otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, Chicago, USA.

- Puig de la BM (2017) Matters of care, speculative ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, US.

- Puig de la BM (2012) Nothing comes without its world, thinking with care. The Sociological Review 60(2).

- Milne J (2019) Artists’ books as resistant transmitters. Arts 8(4): 129.

- Piepmeier A (2009) Girl zines making media, doing feminism. New York University, USA.

- Phillpot C (1982) Books, Book objects, bookwork’s, artists books. Artforum 20: 77-79.

- Rabasa M (2019) The book in movement: Autonomous politics and the lettered city underground. University of Pittsburgh Press, USA.

- Sowden T (2019) Exploring appropriation as a creative practice. Arts 8(4): 152.

- Coplans J (1965) Concerning “various small fires” an interview with edward ruscha. Artforum.

- Barad K (2007) Meeting the universe halfway, quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning, durham. Duke University Press, US.

- Latour B, Woolgar S (1979) Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts. Princeton University Press, USA.

- Coplans J (1964) Twenty six gasoline stations artforum.

- Rofes O, Tarruella R, (2011) 80 Encants: The Artist's book as a generator of relationships. ASRI, Arte y Sociedad Research Magazine.

- Rabasa M (2017) Movement in print: Migrations and political articulations in grassroots publishing. Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 26(1): 31-50.

- Flynn A, Bell L (2019) Returning to form: Anthropology, art and a transformal methodological approach. Anthrovision, Vanease Online Journal 7(1).

- Bell L, O’ Hare P (2019) Latin american politics underground: Networks, rhizomes and resistance in cartonera publishing. International Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (1): 20-41.

- Fong S (2018) La rueda cartonera. In: Bell L, Flynn A, O’Hare P (Eds.), Cartoneras in Translation. Cartonera Publishing, London.

- Sitrin M (2012) Everyday revolutions: Horizontalism and autonomy in Argentina. Zed Books, London.

- Colectivo DC (2012) Providencias. Dulcinea Catadora.

- Drucker J (2014) Distributed and conditional documents: Conceptualizing bibliographical alterities. 2(1).

- Johns A (1998) The nature of the book, print and knowledge in the making. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, USA.

© 2022 Jo Milne. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)