- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

The Organization of Work in Craft Enterprises of Ancestral Trades

Baya Chatti, Chedli*

Department of the Social Sciences, Qatar University, Qatar

*Corresponding author:Baya Chatti C, Department of the Social Sciences, Qatar

Submission: June 21, 2019;Published: June 25, 2019

ISSN: 2582-1949 Volume3 Issue3

Abstract

This paper proposes to shed light on the organization of work in a specific work environment; these are the craft businesses of ancestral trades. This category of companies, which is most often seen as a survival of the past, continues to coexist today with modern companies characterizing industrial companies. Based on the results of an empirical study taking a sociological perspective and conducted in Tunisia, this paper envisages identifying the organizational characteristics of this type of companies, especially those organizational structure and organizational units. The aim of such an exercise is by no means to draw a comparison between this category of companies and the companies resulting from the industrial revolution. But it is to see the basic form of the organization of work insofar as this category of enterprises is a survival of the pre-industrial era. The results of the empirical study clearly show that craft enterprises of ancestral trades embody a well-distinguished organizational logic.

Keywords:Craft enterprise; Ancestral trade; Work organization; Organizational structure; Organizational unity

Introduction

The craft enterprise of ancestral trades, which interests us in this paper, has long been regarded as a survival of the past insofar as it is inherited from pre-industrial times. This type of enterprise concerns, in fact, productive units that practice traditional trades inherited from the past and which are characterized by the dominance of manual work. At a time when the economy is becoming more global, it has been believed that this type of productive units would be eliminated permanently with the concentration of capital, the evolution of techniques and the abolition of customs borders. None of these phenomena contributed to the disappearance of these production units. At a time when we were, waiting for the definitive eclipse of the organization of artisanal work in the mass production economy (Piore and Sabel, 1984) there is a dramatic resurgence of interest in crafts. This paper attempts to answer the following question: what are the organizational characteristics of the ancestral craft enterprises? The answer to that question is based on the data of empirical research aimed primarily at determining the success paths for this specific category of enterprises in the Tunisian context1. This research was an opportunity, in addition to the basic forms of work organization. This article is structured in three main parts. The first is dedicated to a quick presentation of the main concepts. As for the second, it is devoted to the presentation of the methodological framework of the study. Finally, the third is about the answer to the questions asked above. This last part takes place in two stages. As a first step, the results of the empirical study will be presented. In a second phase, direct responses to the main question of this article will be presented.

FOOTNOTE

11Tunisia is one of the countries where the issue of handicrafts and artisanal production has become very topical; whether in political and economic programmes or in the daily lives of the population. After being marginalized during the first three decades of independence (1960-1980), the craft sector was reintegrated into the country’s economic process towards the end of the twentieth century. From now on, this sector has a fairly large and rather particular interest. There has been a steady evolution in the number of craft enterprises of ancestral trades; between 31 December 2000 and 31 December 2017, this number increased by almost 3: from 622 to 1979 units (ONA, 2017: 6). As part of empirical research aimed primarily at determining the paths to success of this specific category of business, we have the opportunity, among other things, to identify the production dynamics of which differentiate them from other types. whether artisanal or industrial of modernity.

What is craft enterprises of ancestral trades?

The craft enterprises of ancestral trades, which has formed our laboratory of investigation in the research behind the data presented here, has traits that are typical of it. The identification of these production units, which have managed to survive to the present day, is carried out first through the trades practiced. Thus, the traditional trade is the main characteristic of this type of enterprises [2-5]. Each trade gives the group that practices it and as part of his practice, a specific identity that sets them apart from other groups and other executives. It therefore represents an incorporated capital under which the company and its workforce can be classified and identified. “The profession is a group of culture: it is passed down from generation to generation, by learning. He has his gestures and tongue that fit into the bodies and assign a framework, the edges of which are not seen as such, to the constitution of the identity of any new entrant. It articulates different statutes without it being possible to reduce their ratio to the wage ratio alone” [6].

The literature on companies in traditional trades refers to the term craft, which represents a particular sociological reality. Crafts express ancestral activities devoted to the manual production of objects without the implementation of industrial means. The craft enterprise is characterized, in fact, by the predominance of manual work and the primacy of man over the machine. The machine in this specific world of production does not occupy a central place. She is only an auxiliary to the craftsman’s work2 [7-9]. As a result, manual work is another key element through that the ancestral craft company can be identified and differentiated from other types companies. The predominance of manual labour in craft enterprises of ancestral trades can only reflect the centrality of the human factor in this particular type of productive unit. An enterprise is said to be craft of ancestral trades, when it incorporates individuals who have the specific characters and professional skills relating to a specific trade and who behave in [10]. Moreover, the profession is always presented as a community that prescribes to these individuals a set of rules and duties that must be respected during the professional practice [11]. “The strength of the profession, and in particular of the profession acquired by learning, is to give beings social cues. This leads to behaviors that tradespeople know and will recognize” [12]. Therefore, the profession governs the conduct in the work through the standards that structure it. But these standards are far from being imposed from the outside. Rather, they are the proper construction of the individuals who practice it [12]. In doing so, conduct within a given organization is an essential element through which the image of that organization can be constructed. Beyond this observation, the craft company of ancestral craft presents itself as a learning environment rather than a simple work environment composed of craftsmen and not just workers.

FOOTNOTE

2The sociological works, in particular the work of Bernard Zarca, which focused on the crafts, and the works of Reynaud Sainsaulieu, Claude Dubar and Michel Lallement in France who studied the question of the identity of individuals within the corporations and trades, show that handicrafts represent a particular sociological reality. This can be justified by several points, such as the importance of social relations within it, the shared awareness of its members of their belonging to a specific social class, the primacy of man in the process of production, its perception as a separate social group. Etc.,

“In general, it can be said that the craftsman is the one who knows how to work the material in accordance with the rules of the art in order to create or produce a work. By rules of art, I mean, the rules that ensure the consistency of a work in terms of quality of use, technical functionality and aesthetics, but I also include ethics. When we say that a craftsman “has a craft” it means that he has experience and know-how, but also that he knows how to make sense of his work, to understand how others will use it. In this sense, the craftsman must be able to know, whether or not, to know a particular piece will find its place in his work [13]”. Thus, the characteristics of craftsmen present themselves as a criterion to distinguish the craft enterprise of ancestral craft. In brief, the identity of the company, so-called ancestral craft, is also largely determined by the qualities and behaviors of its staff.

The organization of work

Talking about the organizational characteristics of companies mainly means, focusing on one of the central concepts in occupational science. This concept is the organization of work. To define this concept, which is an important part of any production unit, we have referred to a fairly broad literature belonging to several science that is interested in the world of work and business. This exercise allowed us to see that the organization of work is broken down into two dimensions: the structure of the organization and the organizational units. From an organizational point of view, structure refers to how parts of a whole are organized together [14]. “The structure of the organization,” writes Mintzberg, “is the set of formal and semi-formal means that organizations use to divide and coordinate their work in order to create stable behaviors” [15]. The structure of the organization, therefore defines a certain arrangement between the parts of the business, to the extent that it represents an organization and operates according to a given organization. The work of Mintzberg offers a range of indicators to qualify the nature and weight of the structure of a given organization. Two types of organizational structure can be distinguished Heavy structure and light structure.

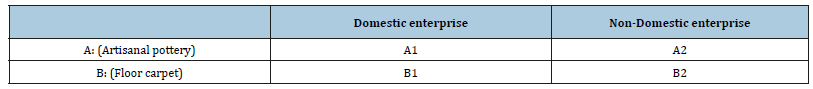

As for the second dimension relating to the organization of work, it concerns organizational units. The study of these allows us to see the characteristics of the organizational functioning of companies [16]. In fact, to be interested in organizational units is to be as close as possible to the concrete situations of work [17]. In order to make operational, the two main dimensions of the organization of work, we referred to the literature and the results of previous research in the field organization. The latter two provide us with a range of elements to observe and identify the two components of the organization of the work we have chosen. From this range of elements, we have chosen the ones that we found most useful in identifying the structural and organizational characteristics of craft enterprises. The Table 1 below illustrates the elements through which the organization of work has been made observable, even operational.

Table 1:The operationalization of the notion of work organization.

Methodology

This paper aims, let us remember, to develop a sociological understanding of the organizational characteristics of craft companies of ancestral trades based on the results of a survey empirically. With such a methodological orientation, the approach of this study is par excellence an inductive approach. The choice of departure was to collect purely qualitative data to understand from the inside the ‘work organization’ who is the subject of our investigation. In practical terms, the data underlying our analysis come from semi-directed individual interviews and direct observation of concrete work situations in the units studied. With respect to the first source of data, we conducted 47 semi-directed interviews with people in craft enterprises of ancestral trades. With regard to the second data source, direct observations of the actual situations of production were made within four production units. In doing so, the analyses advanced in this paper are deeply rooted in reality. This is made possible by mobilizing the anchored method during the data analyze3 stage. The following Table 2 represents in a more detailed way the distribution of the sample of study.

Table 2:Distribution of sample units.

Presentation of results

After identifying the various frameworks of the research in the first part of this paper, the second part is devoted to presenting the results obtained from the empirical study. The presentation of data for each of the four units studied will be performed separately.

The organization of work in the enterprise A1

Direct observations of the concrete situations of production in this company lead to the conclusion that the organization of work is characterized by simplicity and flexibility. This is justified by the following three points:

a. The absence of a spatial and formal division of labour: the various operations relating to the production process, with the exception of firing, take place in the same room. In addition, all members of the company participate in the various phases of this process. Yet the absence of a formal division of labour doesn’t mean the absence of an informal organization and division of the production process. The organization and division of tasks is based on the availability of family members, the nature of the task, gender and orders received.

b. The juxtaposition of the hierarchy of the company with that of the family: considering the production in this company represents a task inseparable from other domestic tasks, it would therefore be difficult to talk about hierarchical categories on professional bases in this case. In such a situation, family logic prevails over corporate logic. As a result, the company’s hierarchy is only that of the family.

c. The centralization of decision-making: the master craftsman in this enterprise presents himself as the central point of power. The accumulation of the statutes, the father and the boss, strongly legitimizes his authority over the other members of the company. However, the centralization of decision-making doesn’t mean that the leadership style adopted is authoritarian. He’s more of a paternalistic type. The father occasionally seeks the advice of his family members when making a decision. However, he remains the master on board in the company. «We learned wisdom from him, so how we can’t approve of his decisions. In fact, almost all the craftsmen and even the officials in the city come to ask him for advice. Thanks to his experiences, he became the reference in the city.” (The master craftsman’s son-in-law).

In light of the above, the organizational structure of this enterprise, despite its centralization around the chef company, is of a simple type. The main elements of this type of structure, theoretically described by Mintzberg [16], are easily identified in this case: the formation of a single working group organized in an informal way, lack of organizational units, imprecise division of labour, etc.

The organization of work in the enterprise A2

Unlike the enterprises A1, A2 is characterized by the presence of a semi-formal organization of work. However, this doesn’t reflect the implementation of written regulations that determine the roles of everyone or prescribe tasks within the enterprise. The semiformal character of the work organization is observed mainly in the layout of the workplace than in the operation of the enterprise. In terms of workplace planning, this enterprise is divided into different spaces. Each of the production operations takes place in a separate room. This spatial division takes the form of a chain. In addition to the space division of the workplace, A2 is made up of several production units. The members of each of these units take a very specific stage of the production process. In addition to dividing production into different units, the owner of this company shares management business with his brother. He is himself responsible for external affairs (the sourcing of raw materials and the marketing of products) as well as human management within the company. Despite the presence of several organizational units, the hierarchy within this company can be described as simple. All production units are under the supervision of one person: the brother of the owner of the business. Similarly, there is no subordination relationship between members or between units. This means that the organizational structure in this company is simple, as the line is very short and coordination between the different production units is easy. This is all the more justified by the centralization of decision-making power. But that doesn’t mean that the management in this company is authoritarian in style. The owner says: “Before introducing any change within the company, I consult with all members. Their opinions mean a lot to me because they will be the main ones affected by this change. “With such a style of management, the chief of the enterprise A2 fits into modern management modes. The advisory style, which he applies in his production unit, remains one of the most applied management styles in modern production worlds [18].

The organization of work in the enterprise B1

On an organizational level, The B1 enterprise consists of a single production unit that brings together all the members operating in it. However, there is a certain division of work. This division, which is based on the professional skills of the members of the company, concerns only the tasks and not the workspace. Indeed, this company consisted of one piece. The different corners of this room are used to store the raw material (wool) and the final product (carpets). The chief of this enterprise occupies a prominent place. This is reflected in his involvement in the different phases of production and in the centralization of power. The chef decides, without consulting any of the accompanying craftswomen, the model and size of the carpet as well as all other cases relating to the process of manufacturing. Such a monopolization means the presence of a hierarchy within this company. This hierarchy can be described as very simple since it is composed of two categories: the leader on the one hand and the craftsmen who work with her on the other. This hierarchy is therefore not structured according to professional skills, but according to the disposition of the means of production. This logic of distribution of power within this company is confirmed by the absence of separate professional categories. This absence doesn’t in any way express the standardization of skills and professional experience within this production unit. Taking into account the above, the organization of work in this company is very simple in nature. There are two reasons for this conclusion. On the one hand, its organizational structure is typically artisanal [15] since it is composed of a single group organized informally. This informality is reflected, among other things, in the absence of a fixed work schedule. The craftswomen come to the company after completing their domestic duties. Indeed, the temporal organization of work does not comply with any regulations. On the other hand, it consists of a single organizational unit.

The organization of work in the enterprise B2

As for the structure of the organization of the enterprise B2, it is far from being an artisanal structure. Rather, it is a fairly complex structure. This is manifested in the division of labour, the hierarchy and the system of power structuring the organization of the productive activity of this company. About the division of labour, B2 is characterized by a careful division of tasks and activities related to the production process. In addition to this division of tasks, the workspace consists of five separate rooms. Thus, the tasks are carefully divided, and the activities are spatially separated. About the hierarchy, the B2 enterprise operates according to a welldefined organization structure. This organization structure consists of four hierarchical categories: the entrepreneur, the heads of production units, the production line managers and the craftsmen. Such a categorization indicates to the presence of a hierarchical line within this company. Decision-making is totally monopolized by the head of this company4 . We were never consulted when determining the carpet models to be made. The chief prescribes the models for us. Then, as a line manager, I pass the message on to the production craftswomen” (Line manager aged 43).

With respect to the organizational units that make up this company, they are of two orders:

a. The warping unit.

b. The weaving unit.

The coordination between these two units is done through the direct interaction between the head of the warping unit and the head of the weaving unit. As mentioned above, the organization of work in the enterprise B2 differs from the artisanal model of organization in two main aspects: the more or less complex organizational structure and the presence of more than one organizational unit organization within the company.

Discussion of the Results

The data presented above, show that the organization of work in craft companies of ancestral trades is far from identical. It varies in one trade to another and even from one company to another. This confirms one of the most common ideas in the fields of work sciences: the organization of work depends mainly on the culture of the company. The latter is in turn influenced by the culture of the profession which represents an integral part of the culture of whole society [19]. However, a thorough analysis of the data in question allows us to identify The organizational characteristics common to all production units studied in this study. Such a consequence means, among other things, that craft companies in ancestral trades share the same organizational logic. In other words, the organization of work, in production environments that practice occupations inherited from the pre-industrial era, is strongly imbued with the economic, social, cultural and technical contexts that differentiate the era. in question from the industrial era. In practical terms, the aggregated empirical data can be used to determine the organizational characteristics of the class of enterprise under consideration. In accordance with the operational framework implemented to observe the variable the organization of work in the units studied, these characteristics are related to the two main dimensions that make up the variable in question: the structure of the organization and organizational units.

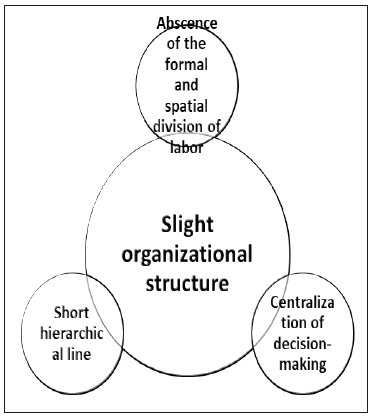

The structure of the organization in craft enterprises of ancestral trades

Empirical study clearly shows that craft enterprises of ancestral trades are characterized mainly by their very simple and light structures. This type of structure differs from other types of structure mainly by organizational proximity. In fact, proximity is one of the main elements through which these companies can be distinguished from others. This is the first-time proximity it clearly appears in the majority of studied cases, particularly in enterprise A1, A2 and B1. In these companies we have noticed the virtual absence of the formal technical division and spatial and spatial production activity. This organizational proximity has led to another type of proximity which is social proximity. This is mainly manifested in interpersonal relationships outside and in work. These relationships in the four studied enterprise, regardless of whether trade and their category of belongings, are far from bureaucratic relationships, they are rather empathic. In other words, the small size of the craft enterprise fosters face-to-face relationships between all its members. So, interactions are another main feature of the craft business. This is also made possible by another element related to the structure of the organization which is the hierarchy.

In the four studied enterprises, with the exception of the enterprise B2, the hierarchy remains another element on which we have relied to describe the structure of the organization in craft enterprises of ancestral trades of simple and light. In fact, these companies are characterized by the short length of the line that provides the link between the different components of the company. The short length of the line reflects, among other things, the absence of several hierarchical categories within the craft enterprises of ancestral trades. According to Henri Mintzberg, one of the principal investigators on the issue of organizational structures, the small number of hierarchical categories is one of the characteristics of the lightweight organizational structure [15]. The lightness of the organizational structure in the craft enterprises of ancestral trades is also confirmed by another element directly related to the organization of work, which is the power, which manifests itself, mainly, in decision-making. In the four companies that were the subject of our investigation, decision-making is almost centralized to the extent that it is monopolized by the owner of the company that is involved in all activities related to the operation of the business. This situation is consistent with another specificity of light organizational structures described by Henri Mintzberg in his famous book Structure and Dynamics of Organizations [15]. In short, the structure of the organization in ancestral enterprise of ancestral trades can be summarized schematically as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1:The organizational structure in craft enterprises of ancestral trades.

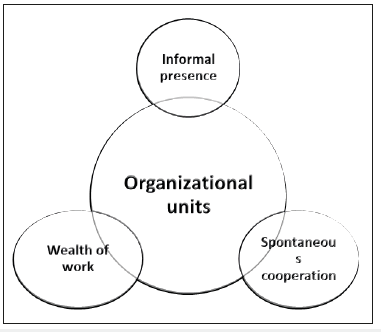

Organizational units in craft enterprises of ancestral trades

Organizational units, it should be remembered, are the second dimension of the variable of work organization that interests us in this paper. This dimension was observed in this study through three elements; who are in narrow relationship with Concrete situations work, in this case with the actual organization of the work. These elements are: the organization of the production unit, the content of the work and the relationships between the units [20,21]. The latter have been mobilized, also, to identify the organizational characteristics of artisanal enterprises in ancestral trades. The data of the four enterprises in our study allowed us to identify three main findings relating to organizational units in craft enterprises of ancestral trades:

a. Craft enterprises of ancestral trades are organized in appearance in a single unit of work, insofar as, the skills of their members are diversified and don’t concern not a single task. Such a situation expresses the absence of formal organizational units. However, there are informal organizational units imposed by the nature of the trade that requires the separation of the various components of the production process. In fact, there is no real separation between design and production. The work within the craft company is, in fact, not divided between those who prepare and plan the production tasks, and those who perform these tasks as is the case enterprise applying an industrial production model. Therefore, the separation between skilled and unskilled work is cancelled in the artisanal context of production [22].

b. The content of work in craft enterprises of ancestral trades is characterized by wealth. This mainly reflects the centrality of the human factor in this type of enterprise, in which human work prevails on the machine. This provides another criterion for organizational labelling of this type of production unit. This criterion corresponds to the knowledge and know-how of the individuals who compose it. The latter are generally described as persons with specific skills that give them the status of craftsman.

c. Relationships between organizational units in craft enterprises of ancestral trades , despite their informal presence, are relationships based on cooperation and coordination both mechanical and organic; i.e. that cooperation between these units are not organized not only on technical bases but also on sociocultural bases relating to the trade and the working group.

In short, the characteristics of organizational units in ancestral craft enterprises of ancestral trades can be summarized schematically as follows (Figure2). Having identified the characteristics of the organizational structure as well as those of the organizational units relating to the craft enterprises of ancestral trades, we can see the absence of certain elements that can be other types of companies, including industrial-type companies. In the end, it can be inferred that craft enterprises of ancestral trades embody a typical organizational model that differentiates them from all other types of enterprises. This model consists of a single informally organized group. Coordination within this group is done through the standardization of qualifications. Similarly, the artisanal organizational structure is a small, undeveloped structure in which the division of labour is imprecise [23]. As a result, the process of production within the craft enterprise is characterized by simplicity, the small number of participants and the virtual absence of subordination insofar as everyone has a complete knowledge of the entire production process.

Figure 2:Organizational units in craft enterprises of ancestral trades.

Conclusion

The main objective of this paper was to determine the basic form of work organization. This is made possible through the study of workplaces practicing occupations inherited from the past, particularly from the pre-industrial era that saw the emergence of new forms of work organization characterized largely by complexity and extreme rationality. This study, which took place in concrete cases in craft enterprises of ancestral trades in Tunisia where we are witnessing the strong presence of this type of enterprise, shows clearly that the basic form of work organization, where also the artisanal form of work organization, is completely different from that characterizing companies modern industrial enterprises. The artisanal form of the organization of work differs from that of industrial type by several traits. In practical terms, the differences between the two organizational models lie at two main levels: the structure of the organization and the organizational units. In both cases, the ancestral craft enterprises is characterized by simplicity and the absence of formal and standardized rules. But this does not mean that the organization of work in the world of craft enterprises of ancestral trades is less productive.

On the contrary, the reality on the ground clearly shows that the artisanal organizational model promotes both, increasing individual productivity as well as the collective. Similarly, this model ensures great satisfaction among workers as it values their know-how as well as their creativity. Such a situation makes the individual more attached and engaged in his or her workplace. Moreover, innovation at work is strongly present in craft enterprises of ancestral trades. Indeed, the artisanal organizational model, which represents the basic form of work organization, can be a solution for modern-day companies that are required to be innovative to become in a context characterized by hyper-competitiveness. In a word, the return to the artisanal organizational model becomes a necessity it can be beneficial on two levels: 1-face the problems stemming from the industrial model and 2-make the company more competent in an increasingly uncertain market.

References

- Piore JM, Sabel CF (2010) The paths to prosperity: From mass production to specialization. Hachette, New York, USA.

- Jaeger C (1982) Craft and capitalism: The other side of history. Payot, Paris, France.

- Zarca B (1987) Artisans, tradespeople, people of talk. L Harmattan, Paris, France.

- Picard CH (2006) The identity representation of artisanal TPE. International Journal PME 19(3-4): 13-49.

- Allard F (2008) The enhancement of the specifics of artisanal enterprises. Annals Network Crafts-University.

- Zarca B (1988) Identity of craft and craft identity. French Journal of Sociology 1: 247-273.

- Ajam BM (1937) Corporate Doctrine. Siery, Paris, France.

- Zarca B (1979) Crafts and social trajectories. Social Science Research Acts 229: 3-26.

- Pacitto JC, Huet RK (2004) In search of craft enterprise, 7th Frenchspeaking international congress in entrepreneurship and SMEs, Montpellier, France.

- Robert M, Durand M (1999) Artisans and crafts. PUF, Paris, France.

- Tunnies F (1977) Community and society: Fundamental category of pure sociology. Retez, Paris, France.

- Casella TP (1985) Dynamics of trades, constraints and resources of trade culture. Rural economy, p. 169.

- Hughes E (1966) The sociological eye: Selected essays. ÉHSS, Paris, France.

- Jouffroy G (2004) The meaning of the craftsman. Constructive, p. 9.

- Conso P, Hemici F (2003) The company in 20 lessons: Strategy, management, operation. Dunod, Paris, France.

- Mintzberg H (1998) Structure and dynamics of organizations. Organizations. (12th edn), Paris, France.

- Soparnot R (2006) Organization and management of the company. Dunod, Paris, France.

- Osty F, Sainsaulieu R, Uhalde M (2007) The social worlds of business. The Discovery, Paris, France.

- Likert R (1961) New patterns of management. Mc Graw Hill, New York, USA.

- Thévenet M (2006) Corporate culture. PUF, Paris, France.

- Chatti BC (2016) Craft enterprises in the context of globalization. Pre- University Education, India.

- Klein L (1976) New forms of organization. Cambridge University Press, New York, USA.

- Zarca B (1982) The economic rationality of craftsmen. Consumers 1: 3-38.

© 2019 Baya Chatti, Chedli. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)