- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

Axe Grinding Grooves in the Absence of Axes: Neolithic Axe Trade in Raichur Doab, South India

Arjun R1,2*

1 Department of History and Archaeology,Central University of Karnataka, India

2 Department of AHIC & Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, India

*Corresponding author: Arjun R, Department of History and Archaeology, School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Central University of Karnataka,Kalaburgi,AHIC & Archaeology,Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune, India

Submission: November 01, 2017;Published: June 27, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume2 Issue2

Abstract

In the semi-arid climate and stream channel- granitic inselberg landscapeof Navilagudda in Raichur Doab (Raichur, Karnataka), sixteen prominent axe-grinding grooves over the granitic boulders were recorded. Random reconnaissance at the site indicated no surface scatter of any cultural materials including lithic tool debitage. Within a given limited archaeological data, the primary assertion is, such sites would have performed as non-settlement axe trading centre equipping settlement sites elsewhere during the Neolithic (3000-1200BCE).Statistical and morphological study of the grooves suggests the site was limited to grinding the axe laterals and facets, and there is no such grooves suggesting for axe edge sharpening which could have happened elsewhere in the region or settlement sites.

Keywords: South Asia; Southern neolithic; Axe-grinding grooves;Lithic tool strade

Introduction

The technological innovation of grounding axes/celts developed during the Neolithic culture [1-3]. Three stages in the reduction of lithic blanks to finished axes were flaking, pecking and grinding/ polishing/grounding. The last stageis laborious [4,5], and crucial to understand the significance of partially to fully polished tools in the society and economy. In addition, the shallow depressed groove over the bedrocks and boulder surfaces occurred because of grounding different angles of the axe; provide insights into understanding the very significance and functionality of thelocation. The culture in focus here is Neolithic of south India (3000-1200BCE), which is one of the distinct temporal and culturally diverse region in the Indian subcontinent [6,7]. Southern Neolithic sites are studied since Robert Bruce Foote explorations during 1860-70 [8]. Various research problems exist in the studies of southern Neolithic culture including the origin of ashmounds, pastoral and pastoral cum agriculture site economies depending on the regional landscapes, the mode of chaîne opératoire for dolerite and cryptocrystalline-based lithic tool production, settlement patterns etc. We are yet to deal with the dolerite tool technology including celts, blades and chisels that are available at both settlement and workshop sites from different locales. Despite the celts being well known in the Neolithic sites, axe-grinding grooves are also known categories in the southern Neolithic research that are not subjected to analytical operations in common to understand the importance and contribution of such workshop locales in the background of site or regional economy.

Dolerite Axe and the Grooves

From past c 150 years, dolerite axes, due to their representative evidence for Neolithic culture have remained as a favourite collection tobearchived. On the other hand,we have made a least attempt in recording the morphological and technological features in the axes. Three methods in axe reduction are noticedfrom the dolerite axe assemblages of Sangankallu-Kupgalcomplex [3]. The axes were slab based, block based and flake based reductions. Despite irrespective of reduction methods, the last stage is grinding the tool by grounding dorsal, ventral, laterals and edge or neither of three facets against the bedrock or boulder.

Grounding of axes results in the formation of grooves over the bedrock, and they are common in the dolerite lithic workshop sites and workshop cum settlement sites in North Karnataka (South India). Example, Sangankallu-Kupgal[5,9-12], Budihal[13],Piklihal [14] andMaski [15]etc.Morphological study and contextualising them in the broader aspects of locale importance and functionality including the axes were neglected, and works at Sangankallu- Kupgal emergedas a single reference to study them in detail with experimental worksto differentiate among the axe grinding and grain processing grooves. Sangankallu-Kupgal complex considered as a major Neolithic axe-manufacturing centre [8]. Excavations have exposed axe manufacturing workshop in the presence of boulders with grooves [3]at the foothill, and loads of dolerite quarry deposit over the hilltop of Hiregudda.Axe grinding grooves of Sangankallu- Kupgal complex have been quantified, recorded for their functionality and attempted on any possible data could be retrieved on the types of celts that were grounded [3,5].

Navilagudda Axe Grinding Site

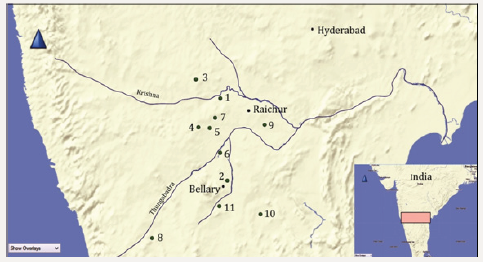

Recent explorations in Raichur Doab, including right bank of Krishna (district in Karnataka) are locating number of sites belonging to different prehistoric and later prehistoric phases in the diverse landscapes. One such site is Navilagudda (meaning peacock hill in Kannada dialect) locatedover the right bank of Herundi downstream (3km south of Krishna) at Devadurga taluka, Raichur district (Figure 1). This is neither dolerite dyke nor gravel available location but is a landscape of granitic knobswith pea size to stony gravel cover under semi-arid climate (Figure 2). On the southern foothill boulders at three localities,traces of sixteen axe-grinding grooves were found in absence of lithic tools or any occupational evidences (Figure 3). Presently the site is affected by agricultural landscaping, and further reconnaissance in an area of 1.5km radius centring the grooves site did not indicate any traces of cultural activities on the visible surface. A detailed statistical recording and morphology of the grooves were initiated with the attributes of length, width, depth, cross section shape and vertical shapes in an attempt to understand which part of the axe was grounded(Figure 4).

Figure 1: The following are sites mentioned in the manuscript. 1) Navilagudda. 2) Sangankallu-Kupgal. 3) Budihal 4) Piklihal 5) Maski 6) Tekkalakota 7) Watgal 8) Hallur 9) Utnur 10) Pallavoy 11) Brahmagiri Site 2,4,5,6,7,8 and 11 are multi-period sites with Neolithic and Iron age culture. Site 1 is Navilagudda as a case study in this research. Site 2, 3, 8, 9 and 10 are Neolithic ash mound sites. All sites are in North Karnataka, central Karnataka and Telangana (9 and 10) states of India. Semi-arid in climate and Southern Deccan in physiography

Figure 2: General view of the site Navilagudda on the tributary stream of Krishna at Devadurga taluka, Raichur. The landscape is granitic knobs and residual hill with pea size gravel sediment. Few boulders in the insight bears axe grinding grooves.

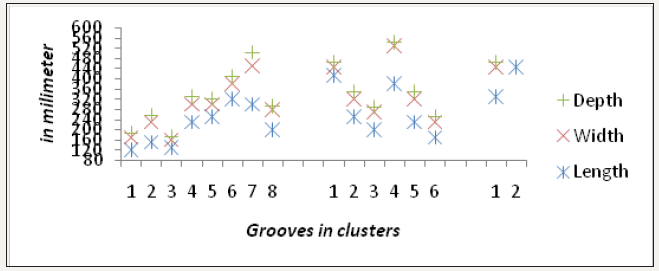

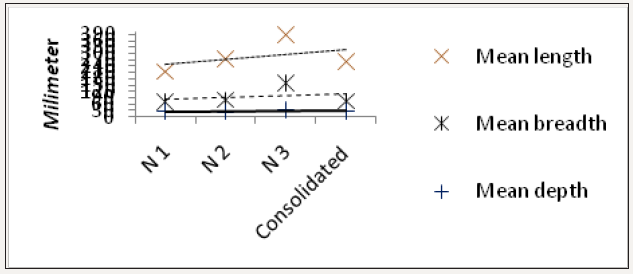

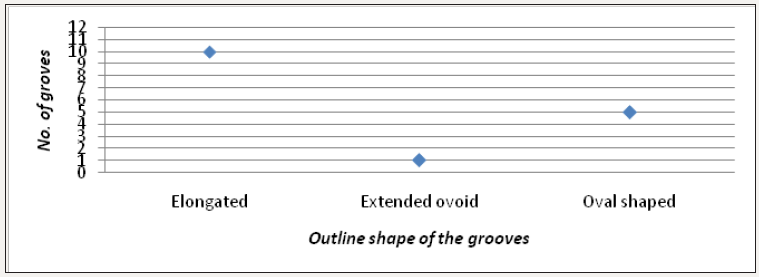

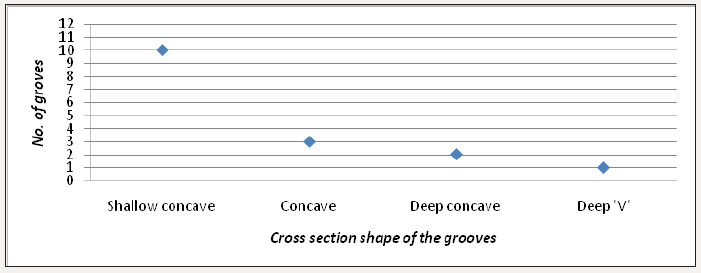

Statistics and morphology:Groove length range from 130mm to 380mm, width range from 30 to 200mm and the depth range from 12mm to 30mm (Figure 5). Mean length is 258mm, mean width 72mm and mean depth is 25mm (Figure 6). Their length, width and depth expansion is reciprocal to each other depending on the grounding of the tool. The shape of the grooves like lithic tools could be classified into vertical and cross section shapes (Figures 7& 8). 63% of the grooves are elongated in outline (N10), 32% (N5) are extended ovoid and < 5% are of oval shaped (N1) grooves. Their cross section shapes differ from being shallow concave (63%/N10), concave (19%/N3), deep concave (< 13%/N2) and deep ‘V’ (< 5%/ N1).

Figure 3: Elongated ovoid and deep concave type of grooves suggesting axe facets grounded over the bedrock/ boulder from the site of Navilagudda.

Figure 4: Elongated and deep V shaped by cross section grooves suggesting axe laterals grounded, from Navilagudda.

Figure 5: Dimensions of sixteen grooves from three clustered localities of Navilagudda.

Figure 6: Mean statistics of sixteen grooves from three clustered localities of Navilagudda.

Figure 7: Categories in vertical shape of sixteen grooves from three clustered localities of Navilagudda.

Figure 8: Categories in cross section shape of sixteen grooves from three clustered localities of Navilagudda.

Discussion

Southern Neolithic offers distinct material evidences to study their cultural economy ranging from stone tools and ceramics, ashmounds, rock art, botanical and faunal evidences. Budihal [16], Watgal [17],Brahmagiri [18], Piklihal[14], Utnur[19], Maski[20], Pallavoy[21], Tekkalakota[22], Hallur [23] and Sangankallu Kupgal[9] are few excavated ashmound, settlement and lithic workshop sites (Figure 1). Larger numbers of polished axes wereretrieved, but the grooves have been reported only from Sangankallu [9], Maski [20] and Budihal [16]. Axe productions at Sangankallu- Kupgal were intensified during 1400-1200 BCE [3,5,9,24]while the site witnessing socio-economic transformation including catering lithic needs to local population and expanding axe trade on a long distance. Possibly reaching Neolithic settlement sites (with ashmounds and rock art but not lithic tools production sites) like Piklihal & Budihal[24].Larger load of dolerite debitage and mining products with good number of grooves suggested edge sharpening and butt treatment at Sangankallu- Kupgalwere intensified, and celts would have left this site only after reaching through all the three stages in the making of axes.

Schaw [1], McCarthy [2], Kennedy [25], Delage [26] and Risch et al. [5] observe that the grooves’ periphery, bevelled edges and the butt gets grinded in the case of convex hollows that are wider, flat or U section, and lateral edges were polished in the case of latter. Whereas, grooves from the site of Navilagudda do not indicate at edge sharpening of the celts, and neither found associated with lithic blanks or tools or debitage[27]. The morphology of the grooves suggests the site was limited to celts grounded for lateral and facet grinding, and not for sharpening of axe edge.In addition to the above hypothesis, this research attempts to highlight the possibility of axe trade networking during the Neolithic in vagueovercoming a multiple process before reaching them into the hands of consumers. The central areas of western part of the Raichur Do-ab have dyke capped granitic valleys from where dolerite blanks were collected or even flaking and bifacial trimming or pecking would have conducted on site, and grounded elsewhere like in the location of Navilagudda before they were supplied to far distant Neolithic settlement sites. Such axe grinding groove sites areanticipatable[28], probably perhaps, in good numbers in western part of Raichur Do-ab. There still exist a major gap in bridging the networking between the resource location-workshops and consumers in the occupational sites through highlighting such sites of Navilagudda.

Acknowledgement

This research is a part of the author’s doctoral program, and supported by Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), New Delhi through a Junior Research Fellowship.I am thankful toMr. Dundappa (resident of Devadurga, Raichur) for logistic support and Mr. Praveen Kumar for accompanying in explorations.

References

- Schaw CT (1944) Report on excavations carried out in the cave known as Bosumpra at Abetifi, Kwahu gold coast colony. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 10: 1-67.

- Mc Carthy FD (1976) Australian aboriginal stone implements. The Australian Museum Trust, Sydney, Australia.

- Brumm A, Boivin N, Korisettar R, Koshy J, Whittaker P (2007) Stone axe technology in Neolithic south India: new evidence from the sanganakallu-kupgal region, mid-eastern Karnataka. Asian Perspectives 46(1): 65-95.

- Allchin FR (1957) The ground stone industry of the North Karnataka region. Bulletin for the School of Oriental and African Studies 19(2): 321-335.

- Risch R, Boivin N, Petraglia M, Gomez-Gras D, Korisettar R, et al. (2009) The prehistoric axe factory at sanganakallu-kupgal (bellary district), Southern India. Internet Archaeology, UK, p. 26.

- Paddayya K (1973) Investigations into the neolithic culture of the shorapur doab. E J Brill, Leiden, Netherlands.

- Korisettar R, Fuller DQ, Venkatasubbaiah PC (2002) Brahmagiri and beyond: the archaeology of the southern neolithic. in: Settar S, Korisettar R (Eds.), indian archaeology in retrospect: prehistory, archaeology of South Asia. Indian Council of Historical Research and Manohar Publishers, New Delhi, India, pp. 313-481.

- Foote RB (1916) The foote collection of indian prehistoric and protohistoic antiquities: notes on their ages and distributions. Government Press, Madras, India.

- Korisettar R, Prasanna P, Sanganakallu (2012) In history of India: Proto historic foundations. In: Chakrabarti DK, Lal M (Eds.), Vivekananda International Foundation and Aryan Books International, New Delhi, India, pp. 824-842.

- Boivin N, Brumm A, Lewis H, Robinson D, Korisettar R (2007) Sensual, material and technological understanding: Exploring prehistoric soundscapes in south India. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13(2): 267-294.

- Subbarao B (1947) Archaeological explorations in Bellary. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 8: 209-224.

- Subbarao B (1948) Stone Age Cultures of Bellary. Deccan College, Poona, India.

- Paddayya K (2001) The problem of ash-mounds of Southern deccan in the light of the Budihal excavations, Karnataka. Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute 60(61): 189-225.

- Allchin FR (1960) Piklihal Excavations. Andhra Pradesh Government Publications, Archaeological Series, Hyderabad, India.

- Johansen PG, Bauer V (2015) Beyond culture history at Maski: land use, settlement and social differences in Neolithic through Medieval South India. Archaeological Research in Asia 1(2): 6-16.

- Paddayya K (1993) Further field investigations at Budihal, Gulbarga district, Karnataka. Bulletin of the Deccan College postgraduate and Research Institute 53: 277-322.

- Deavaraj DV, Shaffer JG, Patil CS, Balasubramanya (1995) The watgal excavations: an interim report. Man and Environment 22(2): 58-74.

- Wheeler REM, Brahmagiri, Chandravalli (1947) Megalithic and other cultures in Mysore state. Ancient India 4: 180-230.

- Allchin FR (1961) Utnoor excavations. Andhra Pradesh Government Publications, Archaeological Series, Hyderabad, India.

- Thaper BK (1957) Maski-1954: A chalcolithic site of the Southern deccan, Ancient India 13:114.

- Rami RV (1996) The prehistoric and proto historic cultures of palavoy, south India: with special reference to the ash mound problem. Government of Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad, India.

- Nagaraja Rao MS, Malhotra KC (1965) The stone age hill dwellers of Tekkalakota. Deccan College, Poona, India.

- Nagaraja Rao MS (1984) Proto histoic cultures of the Thungabhadra valley. Swati publication, New Delhi, India.

- Shipton C, Petraglia M, Koshy J, Bora J, Brumm A, et al. (2012) Lithic technology and social transformations in the South Indian Neolithic: The evidence from Sanganakallu-Kupgal. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 31(2): 156-173.

- Kennedy R (1962) Grinding benches and mortars on Fernando Po. Man 62: 129-131.

- Delage J (2004) Les ateliers de taillenéolothiques en Bergaracois. Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Toulouse, France.

- Morrison KD (2005) Brahmagiri revisited: a re-analysis of the South Indian sequence. In: Jarrige C, Le Fevre V (Eds.), South Asian Archaeology. Recherchesur les Civilisations, ADPF, Paris, France.

- Arjun R (2016) Archaeological Investigations at the Brahmagiri rock shelter: Prospecting for its context in South India late prehistory and early history. Journal of Archaeological Research in Asia, pp. 1-10.

© 2018 Arjun R. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)