- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology: Open Access

The Takfirist Movement from the Perspective of Political Process Theory: A Case Analysis of Tunisia

Chuchu Zhang*

Department of politics and international studies, University of Cambridge, UK

*Corresponding author: Chuchu Zhang, Department of politics and international studies, University of Cambridge, England, UK

Submission: December 25, 2017;Published: May 10, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1949Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

Through the analysis on the Tunisian case by adopting the Political Process Theory, this article tries to discuss about generalize able rules about Takfirist movements. In doing so, I would examine the context and process of the Tunisian Takfirist movement rising after the Jasmine Revolution by focusing on three variables: political opportunities, organizational strength, and framing process.

I argue that the Tunisian Takfirist movement developed through two stages:

A. During the first two years after the revolution, elite divisions and sudden political openness provided favourable opportunities for Tunisian Takfirist to recover and reorganize existent resources, set up Ansar al-Sharia, and achieve small-scale mobilization through their religious-dogmatic framing efforts.

B. In the second stage, whereas political elites gradually bridged their divergences and the state enhanced national supervision over religion related activities, Ansar al-Sharia managed to expand its organizational strength by establishing linkage networks with Al-Qaeda and ISIS, leading forces of two international Takfirist movements, and arouse resonance among radical young revolutionaries by building the “revolutionary frame”, a combination of both processes enabled the movement to expand its supporting base.

Keywords: Takfirist movement; Tunisia; Political process theory

Introduction

In the modern Arab world, Tunisia was regarded as the Arab country most likely to join the third democratization wave, as the country has profound secularization traditions, a large middle class, relatively high status of women and education level [1]. Among the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries which underwent revolutions, Tunisia was quite special because it was the first postrevolutionary country that achieved a smooth transition of power and implemented free and fair electoral systems. However, on the other side of the coin, the country witnessed the rise of terrorism in post-revolutionary Tunisia. And the country suddenly transformed from one of the most peaceful country in MENA to the largest source of foreign fighters heading to join the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

It is estimated that more than 7, 000 Tunisians have already travelled to Iraq and Syria to take part in the “jihad (holy war)” and at least 625 among them have returned to Tunisia [2]. Meanwhile, around 15, 000 Tunisians have been barred from leaving the country due to their suspected connections to Takfirist organizations. Also, it is said that the largest Tunisian Takfirist organization [3,4], Ansar al-Sharia, has a membership of 70, 000 [5]. Takfirism is an ideological branch of Salafism. In Arabic, the word “salaf” means ancestors. In the 8th century, Salafism appeared an ideology that advocated to follow the footsteps of Prophet Muhammad and to look back to a prior historical period. Modern Salafism emerged in 1920s [6] when certain conservative

Sunni Muslim groups proposed that Muslims should only read the original Islamic texts and follow the example of Prophet Muhammad and the first three generations of Muslims [7]. In today’s Arab world, Salafism is often divided into three sections: scriptural Salafism, political Salafism, and jihadi Salafism [8] .Among them, jihadi Salafism combines the concept of “jihad (holy war)” with Salafism [9]. While some religious da’wa groups portray themselves as “jihadists”, many radical Islamic organizations equal “jihad” to violence and advocate overthrowing the regime through violent activities.

Along with the rise of Al-Qaeda, ISIL, and other violent religious groups, Takfirism has aroused increasing attention in the academia [10]. In religious terms, “kafir” refers to non-Muslims; “kufr” is used to describe the Muslims who betray Islam by not observing sharia (Islamic law), refusing to fulfil religious obligations, and collaborating with foreign power to damage Muslims’ interests. Many Islamic extremist organizations consider themselves as “Islamic judges”. They judge Muslims arbitrarily and conduct “takfir” towards the ones they judge as “kafir” and “kufr”. Hence, comparing with jihadi Salafists, Takfirsts not only attack government officials, but also use harsh tactics to punish the civilians who, in their eyes, are not pious Muslims.

Regarding the Takfirist movement, there are basically two perspectives in the academia. The first theory argues that unemployment, housing shortage, growing gap between rich and poor, and other socio-economic factors are main causes of radicalization and breeding grounds for Takfirism [11,12]. The second theory argues that as a religious ideology, Takfirism tends to attract the people who have strong religious sentiments [13,14]. Nonetheless, both perspectives are problematic. In the terrorist attacks that occurred in Tunisia in recent years such as the Bardo National Museum terrorist incident and Sousse attacks, most of the attackers came from middle-class families who not only smoke and drank when they were young, but also attended Western-style parties [15,16]. Thus, it seems that the socio-economic grievances and religious sentiments may not be the only reasons that gave rise to the Takfirist movement. Given the theoretical problems, there needs to be new theoretical frameworks to explain the rise of the Takfirist movement in the MENA after the Arab Awakening.

This article argues that against the backdrop of the rise of Islamic extremism in post-Arab Spring era, to analyze the rise of the Takfirist movement in Tunisia has general theoretical significance, and helps understand the security predicament confronted by Tunisia and other Middle Eastern countries. This article tries to introduce the Political Process Model, a theoretical paradigm employed in sociology. Through the empirical analysis of the Tunisian case, it provides a more convincing theoretical explanation for the background, causes and influences of the rise of the Takfirist movement in Tunisia after the upheaval in the Middle East. It should be noted that the framework used in this article is not limited to the case of Tunisia, nor is it limited to the analysis of Takfirist movements. As an analytical paradigm, the political process theoretical framework can be leveraged to study a wide range of social movements such as the political Salafist movement, traditional Salafist movement, Islamist movement, leftist movement, and far-right movement.

Political Process Theory

Political Process Theory is one of the classical social movement theories. It was originally proposed as a supplement to the Grievance Theory and Resource Mobilization Theory. From late 19th century to the mid-20th century, under the influence of Structural Functional Theory, sociologists generally regarded social movements as the result of social disorder and social groups’ psychological imbalance [17,18]. Yet, this perspective assumed that social movements were irrational and unorganized, and failed to explain why social movements also took place in societies that functioned normally [19,20].

In the 1970s, Resource Mobilization Theory arose. Although this framework acknowledged the rationality of movement entrepreneurs and emphasized social movement organizations’ ability to mobilize resources such as funds, manpower, and technology, not as much importance was attached to the masses as to the elites. Thus, while Resource Mobilization Theory could explain changes dominated by elites, it failed to explain changes dominated by the marginalized groups [21]. To complement the two theories mentioned above, sociologists such as Doug Mc Adam, John D. McCarthy and Sidney Tarrow put forward the Political Process Model. Generally speaking, Political Process Theory viewed the social movement as a medium-term and long-term process which was determined by three important elements: political opportunities, organizational strength, and framing process.

Political opportunities refer to political and institutional opportunities that can promote or hinder collective behaviour [22]. This variable considers level of repression, political openness, and presence or absence of elite allies [23,24].Contentious movement sare more likely to occur when the level of repression declines, political openness increases, and divisions break out among elites. Conversely, social movements are less likely to occur. Nonetheless, favourable political environment only offers opportunities for the dis-satisfied social groups [25] .Whether the discontented social groups can seize opportunities to form organized and large-scale social movements depends on the resources that movement organizations can mobilize. Specifically, social movement organizations’ organizational strength hinges on organizations’ inner structure, recruitment approach, organizational networks and organization cohesion.

The framing process studies how social movement organizations use framing strategies to give legitimacy for collective behaviour, and encourage and persuade social groups to participate in social movements [26]. David A Snow & Robert Benford [27] have pointed out that the outcome of framing process depends on whether social movement organizations’ frames can arouse wide resonance. Empirical experience shows that addressing certain social groups’ common concern and collective identity, or emphasizing their cultural symbols, languages and religions is likely to make the framing process more effective [27].

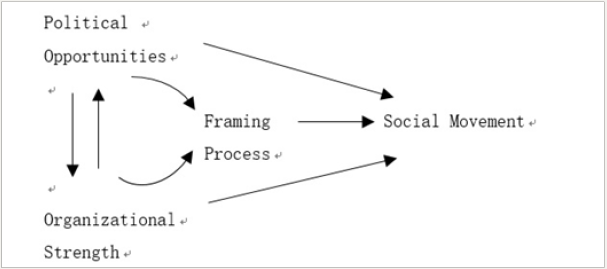

The three elements of the Political Process Model, rather than existing independently, are interacted and play distinct roles in different periods. In the early stage of a social movement, political opportunities constitute a critical factor and determine the choice and scope of activities of social movement organizations and their frames (Figure 1). After social movements emerge in favourable opportunities and enter the expansion stage, social movement organizations’ organizational strength plays a more important role. Strong organizations can use their extensive resources and framing strategies to shape new opportunities, and thus affect social movements’ development. The framing dynamic runs through the whole process of social movements and facilitate social movement organizations to take advantage of favourable opportunities and achieve social mobilization [28].

Figure 1: Relations between the elements of political process model.

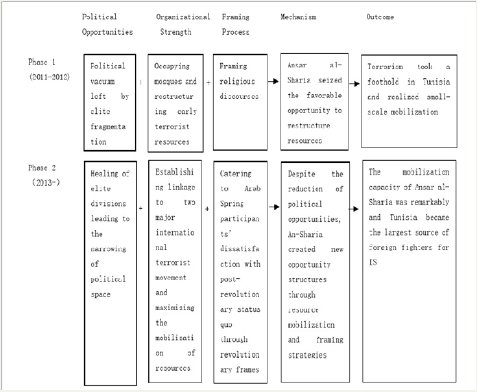

This article analyzes the case of Tunisia, and explains how political opportunities, organizational strength and framing process have affected the emergence and development of the Takfirist movement in post-revolutionary Tunisia. This article argues that Tunisian Takfirist movement experienced two stages of evolution (Figure 2). In 2011 and 2012, the fall of the Ben Ali regime caused a power vacuum in the political scene of Tunisia. The country then witnessed fierce power struggle between political elites, as well as sudden political openness which offered Tunisian Takfirists freedom and space of operation. In this context, Takfirist organizations epitomized by Ansar al-Sharia came into being and attracted a large number of supporters by occupying mosques, creating media outlets and opening social media accounts. After 2013, although political opportunities decreased due to the bridging of divisions between political elites and the strengthening of state’s crackdown against Takfirist movements, Ansar al-Sharia increased its organizational strength by developing internal and external linkage mechanism with international Takfirist organizations such as Al-Qaeda and ISIL. Meanwhile, Ansar al-Sharia strengthened its mobilization capacity by portraying itself as the heir of the Tunisian revolution which resonated with young protesters’ dissatisfaction.

Figure 2: Mobilization process of the tunisian takfirist movement since 2011.

Historical Origins of Takfirism in Tunisia

Tunisian Salafist movements emerged in 1980s when a religious organization called Al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya [29,30] faced with internal division. Mainstream members of the group argued that Islamic texts should be considered in light of contemporary realities, and that the Islamization of the state should be achieved by winning elections. These ideas were rejected by the Salafist section of the group which advocated strict reading of Islamic texts and considered that the timing was not mature for political participation. Under the leadership of Mohammad Khoujia and Mohammad Ali Hurath, this section left Al-and established Tunisian Islamic Front (TIF) [31] which became the origin of Tunisian traditional Salafism and political Salafism.

Since 1991, Tunisian President Ben Ali implemented “Plan for the Cleansing of Resources” and strengthened its control over religious sites and institutions. For instance, the mosques were not allowed to open in non-praying time, and Zaytouna Mosque was prohibited from teaching religious courses [32]. Meanwhile, the regime arrested over 10, 000 Islamists and Salafists. Ennahda and TIF were listed as illegal organizations whose members were either in jail or in exile [33]. Among the Salafists who left the country to avoid repression, a large proportion became militant volunteers in Afghanistan and Chechnya. Receiving training at Taliban or Al- Qaeda camps, these Tunisians got more acquainted with Takfirist ideologies.

In 2000, a group of Salafists who were influenced by international Takfirism including Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi, Sami Ben Khamis Ben Saleh Said founded Tunisian Combat Group (TCG). As an early Takfirist group, TCG aimed to introduce Takfirist ideologies to Tunisia and transform Tunisia into an “Islamic state”. Due to intense monitoring of extremist religious activities by the regime at the time, the group mainly involved Tunisian immigrant population in Europe. The group did not last long and soon started to wane, as its core members including Sami Ben Khamis Ben Saleh Said and Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi were soon arrested in Italy and Turkey, and were then extradited to Tunisia where they were sentenced to life imprisonment [34].

Apart from TCG, another origin of Takfirism in Tunisia was from the Algerian Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et al. Combat, GSPC). Confronting intensive military suppression in Algeria in early 21st century, the group allied with Al-Qaeda, shifted its focus from Algeria to the Sahel desert, and expanded its outreach to neighbouring countries such as Tunisia and Mali [35,36]. In 2007, GSPC was renamed as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Though it established a branch office in Tunisia, its Tunisian branch was soon discovered by the security department and was severely damaged after a fierce battle with security officials, resulting in the death of 12 leaders of AQIM’s Tunisian branch and the apprehension of hundreds of its members [37].

Political Opportunities for Tunisian Takfirist Movements After Middle Eastern Upheavals

After the power alternation in 2011, divisions between elites and sudden political openness offered favourable conditions for the emergence of Tunisian Takfirist movements led by Ansar al-Sharia.

The political vacuum in Tunisia in 2010-2012

At the end of 2010, protest waves toppled Ben Ali’s regime and the original political order in Tunisia, which provided important opportunities for the rise of Takfirist movements. On the one hand, after Ben Ali’s authoritarian regime collapsed, the political environment in Tunisia became more relaxed, leaving more operating space for political opponents and religious groups that had been suppressed in Ben Ali’s era. Several months after Tunisian revolution, over one hundred political parties were legalized, and along with the lifting of restrictions on media, organizations, and religious institutions, thousands of non-government organizations were soon set up. On February 19, 2011, Tunisia’s interim government issued an amnesty law which not only set free numerous imprisoned political prisoners, but also welcomed exiled political activists to return home.

Although the relaxation of political restrictions offered Tunisian citizens more freedom of speech and association and allowed political opponents to participate in formal politics, the negative effects of sudden political openness were also remarkable. For instance, benefiting from the indiscriminate amnesty of political prisoners, around 1, 800 Salafists were set free after the collapse of Ben Ali’s regime [38]. Among them were Takfirists such as Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi and Sami Ben Khamis Ben Saleh Said who had been accused of terrorist activities.

On the other hand, the political vacuum following the collapse of Ben Ali’s regime gave rise to acute power struggle between all sorts of political parties. The political scene was soon marked by confrontation between previous political opponents headed by Ennahda and conservatives who used to be government officials in Ben Ali’s era. The situation was made more complicated by the divisions between Islamist parties epitomized by Ennahda and secular parties within the camp composed of previous dissents. In this context, Ennahda started to co-opt many Salafist organizations including certain Takfirist groups in order to increase its own advantage in the competition with other political forces. Shortly before the election of October 2011, Rached Ghannouchi, head of Ennahda, stated that Salafists “reminded me of my youth” and considered that Salafists were mostly careless youth who needed more education about authentic Islam [39]. During the electoral campaigns of 2011, several Salafist organizations such as Jabhat al-Islah (Front of Reform) mobilized people to vote for Ennahda, which contributed to Ennahda’s victory.

After forming a coalition government with Congress for the Republic and Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties, Ennahda implemented a series of policies that facilitated the spread and development of Salafism. As it is worth noting that at the very beginning Ennahda made little distinction between traditional Salafism, political Salafism, and Takfirism. In 2012, the transition government led by Ennahda legalized several Salafist parties including al-Rahma (Tolerance) and al-Asala (Authenticity), and approved of over 200 Salafist charity organizations and schools which could preach freely in mosques. Additionally, radical religious preachers from Gulf countries and Egypt were allowed to carry out da’wa activities in Tunisia [40,41].

Against these backdrops, there emerged several Takfirist organizations including Ansar al-Sharia (Defenders of the Islamic Law), Al-Jamaa al-Wassatia Li TawiaawalIslah (Organization of Centrist Enlightenment and Reform), etc. Benefiting from favourable opportunities, these organizations used the mosques, websites and social media to disseminate their ideologies and recruit participants. In 2012, at least 400 among the 4, 860 mosques in Tunisia were under the control of Ansar al-Sharia [42].

Change of the political environment in Tunisia after 2013

Since 2013, there has been important change in Tunisia’s political landscape. As far as the Takfirist movement were concerned, the narrowing of operating space due to the bridging of elites’ divisions was a key feature of the political opportunities in the new era. The assassinations of Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi in 2013 rocked the country and intensified the power wrestling between various political parties. Ennahda’s tolerance of the Takfirist movements sparked fierce opposition from secularists ranging from conservatives to leftist forces, and the largest labour union. The Tunisian General Labour Union (Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail, UGTT) initiated national political dialogues. Softening its stands toward secularist rivals, Ennahda took an active part in dialogues with various parties and finally agreed with leftist parties and the conservatives on a roadmap aimed at creating a new technocrat government led by an independent, Mehdi Jomma [43].

Soon afterwards, elites’ divisions reduced as the Islamist party of Ennahda and secularist parties achieved two consensuses. First, they both agreed that former regime officials should be allowed to participate in formal politics and that power alternation should hinge on electoral results. Second, the largest Islamist party, Ennahda and the largest secularist party, Nidaa Tounes, agreed that whichever party won an election and ascended power in the future, the other party should be included in decision-making. A case in point was that although Nidaa Toune won the parliamentary and presidential elections in 2014, it still included Ennahda in the government, which largely reduced divisions between different political parties.

One consequence of the increasing elite alignment was that Ennahda had less motivation to co-opt various Islamist and Salafist organizations including Takfirist ones. In May 2013, Tunisian government banned the third annual conference of Ansar al-Sharia. In August, the group was listed as a terrorist group and its social media accounts and websites were closed down. In 20114, security measures were further strengthened after Nidaa Tounes ascended power. One example was the promulgation of a new counterterrorism law in 2015 which stipulated that any act of prejudicing private and public property, vital resources, infrastructures, means of transport and communication, IT systems or public services should be fined on terrorism charges [44]. The law also reintroduced the death penalty for certain terrorist activities [45].

Establishment of Ansar Al-Sharia and Its Organizational Structure

Taking advantage of favourable political opportunities in 2011- 2012, Tunisian Takfirists started to re-organize original resources and founded new Takfirist organizations epitomized by Ansar al- Sharia. After 2013, Ansar al-Sharia strengthened its organizational dynamic by setting up internal and external linkage mechanism with international Takfirist organizations such as Al Qaeda and ISIL.

Formation of ansar al-sharia and its internal structure

After Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi was set free in early 2011, he redevoted himself to Takfirist movements and contacted the radicals he knew in prison. In April, Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi established Ansar al-Sharia with Sami Ben Khamis Ben Saleh Said who was released together with him [46]. The group first appeared as a cultural charity group in order to avoid attracting official speculation and attention. But the group quickly developed into Tunisia’s largest and most influential Takfirist group, and became the plotter and participant of many terrorist attacks in Tunisia.

Unlike the loosely organized TCG which had been created earlier by Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi, Ansar al-Sharia was highly organized and bureaucratized and had clear division of labours at all levels. Ansar al-Sharia was composed of central and local institutions under the leadership of the group’s Amir (leader), Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi. According to the information posted by Ansar a-Sharia on its social media account, there were at least four central institutes under the leader’s direct control (Figure 3):

A. da’wa committee, which was in charge of religious preaching;

B. humanitarian affairs committee, which aimed to provide food, clothes, medical care and other charity services to the poor and vulnerable groups, and provide relief for victims of natural disasters;

C. media affairs committee, which focused on media propaganda through the group’s websites, social media accounts, and its subordinate media group-al-Bayariq Media Productions Foundation;

D. coordination committee, which was responsible for contacting and coordinating its branches in northern, central, and southern regions [47].

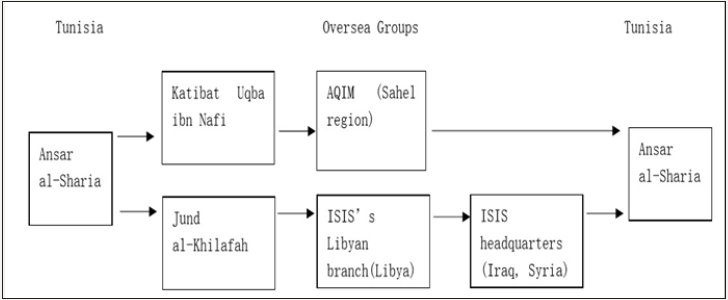

Figure 3: Organizational structure of ansar al-sharia.

Additionally, Ansar al-Sharia had secret military flanks which attacked the ones who it considered as “kafir” or “kufr” [48]. Furthermore, shortly after Ansar al-Sharia was established, it started to contact residual forces of AQIM’s Tunisian branch and set up a militant camp called Katibat Uqbaibn Nafia long with AQIM [49] in the Chaambi Mountain in Kasserine. Apart from launching terrorist attacks in Tunisia, a more important function of Katibat Uqba ibn Nafi was to transfer militants to AQIM, give training to Tunisian Takfirists, and provide a foothold for Tunisian militants who returned from AQIM to their home country. In fact, with the help of Katibat Uqba ibn Nafi, quite a few members of Ansar al- Sharia left for Sahel desert, joined AQIM, and then returned to Tunisia after participating in combats in Algeria and Mali. Besides, Katibat Uqba ibn Nafi also got involved in smuggling at Algeria- Tunisia border and transporting arms and funds to Tunisian Takfirist movements [50].

Building Networks with International Takfirist Movements

In 2014, when ISIL announced the establishment of a “caliphate”, it started to encroach upon Al-Qaeda’s influence in Western Asia, South Asia and Africa. In this context, part of the Katibat Uqba ibn Nafi’s members left the camp and formed a new camp called Jund al-Khilafah (Caliphate Soldiers) which soon pledged allegiance to ISIL and became ISIL’s branch in Tunisia [51,52].

Figure 4: Networks between ansar al-sharia and the international takfirist movement.

It is worth noting that unlike what happened in many other MENA countries where branches of ISIL and those of Al-Qaeda confronted with each other, affiliates of the two international Takfirist organizations presented the trend of integration and mutual aid. In 2014, Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi declared in Ansar al- Sharia’s Twitter account that ISIL and Al-Qaeda had common goals and both sides should set aside differences, work towards new and comprehensive reconciliation [53]. To this end, Abu Ayyad al-Tunisi encouraged members of Ansar al-Sharia to join AQIM on the one hand, and mobilized them to participate in the “jihad (holy war)” in Iraq and Syria on the other hand [54]. By establishing networks with and transporting militants to both AQIM and ISIL through Katibat Uqba ibn Nafiand Jund al-Khilafah, Ansar al-Sharia tried to integrate the Takfirist resources in Tunisia with those in Sahel region, Libya, Iraq and Syria (Figure 4). During the Ramadan in 2014, Ansar al-Sharia declared in a statement that it paid tribute to both the head of ISIL, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and leader of Al-Qaeda, Ayman Al-Zawahiri [55].

The networks that Ansar al-Sharia built with ISIL and Al-Qaeda enhanced its ability to survive and rebound. The tactic was to send more of its militants to international Takfirist organizations whenever the Tunisian government intensified crackdown over Takfirists, and call its militants to return to the country whenever the degree of crackdown decreased. The internal and external linkage mechanism enabled Ansar al-Sharia to continue developing and expanding despite the unfavourable political opportunities after 2013.

Ansar al-Sharia’s Framing Process

When it was created, Ansar al-Sharia mainly used religious frames to mobilize supporters but had limited mobilization effects. After 2013, the organization changed its framing strategies and adopted revolutionary frames, which tapped into the grievances of many protesters who had participated in the revolution of 2010- 2011.

Ansar al-sharia’s religious frames

In the early years since its creation, Ansar al-Sharia adopted religious frames and considered that its chief task was to change the way Tunisians mindset and behaviour in order to revive traditional religious traditions in the society [56]. In 2011-2012, the information Ansar al-Sharia posted on Face book could be divided into three categories: (1) Advising Muslims to practice Islam and follow Habit, and advocating Takfirist ideologies of Ibrahim Rubaish, Abu Yahya al-Labia, and Khalid al-Husainan; (2) Expressing support for Arab Takfirist movements, legitimizing and sanctifying violent actions of Takfirists; (3) Condemning secularists and Western ideas [57], and claiming that faith in democracy is a religion that differed from Islam [58].

All in all, Ansar al-Sharia used favourable political opportunities to re-organize Takfirist resources, established highly bureaucratized organizational structures, used mosques and charity organizations to recruit members, and adopted religious frames to mobilize support. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that there existed numerous religious organizations ranging from radical ones to moderate ones which offered a variety of choices for Muslim citizens. Given that Tunisia was a more open society comparing to other countries in MENA, Ansar al-Sharia’s religious extremist ideas failed to resonate with a large number of people and the group only mobilized a small number of supporters. Although it is hard to figure out the exact number of the group’s sympathizers, the number should be around several thousands. One indication was that around 3, 000 attendees were present at the second annual conference of Ansar al-Shariain Kairouan in May 2012 [59].

Ansar al-sharia’s revolutionary frames

Since 2013, Ansar al-Sharia adjusted its framing strategies and started to use revolutionary frames. Here, the revolution refers to the so-called Jasmine Revolution in 2010-2011 of Tunisia which ousted the regime of Ben Ali who had ruled the country for over 20 years. The slogan of the protesters during the revolution was “bread, freedom, and dignity”, which reflected the protesters’ dissatisfaction with the old regime. Nonetheless, several years after the indignant citizens ousted the old regime, they found that the situation in post-revolutionary era did not necessarily improve.

For instance, the unemployment was still serious, and the corruption was not remarkably improved after the revolution. In this context, Ansar al-sharia tried to cater to these people’s dissatisfactions, and claimed they to be the ones who would continue the revolution, and they said that political parties such as Ennahda actually betrayed the slogans of “freedom” and “dignity” of the revolution by conniving at the officials of the old regime. At the centre of this argument was Ennahda’s abandon of the law on the Immunization of the Revolution. This law had been actively initiated by Ennahda immediately after the revolution which aimed to prohibit the officials of the old regime from running elections so as to prevent them from returning to the political scene again.

Yet, after several years of debates and negotiations, Ennahda’s leader, Ghannouchi, claimed that Ennahda gave up promoting this law, which meant that officials of the old regime were finally allowed to run for elections. Many of them joined the party of Nidaa Tounes and took power again after Nidaa Tounes won the elections of 2014. The group of Ansar al-Sharia condemned the pardon of the old regime’s officials, claiming that Ennahda’s compromise and surrender at such a critical time was a political suicide [60].

And it tried to use revolutionary terms to explain this criticism. It considered that freedom meant “Muslims’ freedom”, and dignity meant “Muslims’ dignity”. It said that in Ben Ali’s era, the secularist regime restricted people’s freedom because it banned the Islamist party of Ennahda, and it prohibited women from wearing veils. Meanwhile, Ansa al-sharia claimed that the old secularist regime damaged Muslims’ dignity because it thought highly of the French language and French culture, rather than the Arabic language and Islamic culture. The group of Ansar al-sharia claimed that the secularists represented by NiddaTounes started to dominate the government again in 2014, which meant that Muslims were again going to lose their freedom and dignity.

Apart from referring to the slogans of “freedom” and “dignity”, Ansar al-Sharia also claimed that people’s demand for “bread” was hardly satisfied after the revolution. In July 2015, the government led by NidaaTounes proposed the National Reconciliation Act Draft, which, once implemented, meant that officials of the old regime who had gotten involved in corruption would be pardoned. Two days after the proposal of the National Reconciliation Act Draft, it was boycotted by thousands of Tunisians [61]. In this context, Ansar al-Sharia started to portray itself as the ones that really tried to implement social justice. In doing so, it not only criticized that national wealth was controlled by elites, but also propagated the charity service it provided. Ansar al-Sharia considered that during the revolution, the protesters demand for “bread” did not simply mean they wanted food, but meant that they wanted social justice. And now, according to Ansar al-sharia, since the government was not going to look into the corruption cases of the old regime’s officials, it seemed less and less possible for Tunisia to have social justice.

To take one step further, Ansar al-shariatried to create the impression that neither Nidaa Tounes nor Ennahda brought bread, freedom nor dignity to Tunisians, which made pointless for citizens to vote in elections? It argued that the goals of the revolution could only be achieved by taking violence. The revolutionary frames turned out to have attracted large number of young protesters who had participated in the revolution in 2010-2011 but were not satisfied with the situation after the revolution. According to a report, there were more than 70, 000 members of Ansar al-sharia by 2014 [62]. In 2014-2016, the group became one of the most important sources of jihadists for ISIL.

Conclusion

The analysis of the rise of Tunisian Takfirist movements has several policy implications:

First, although political opportunities, organizational strength and framing process are all important factors that decide the development of a social movement, their importance in different stages of a movement varies. This article argues that when the Takfirist movement first rises to surface, political opportunities determines whether the movement can exist or not. Monitoring the movement’s activities and controlling its communication channels at this stage are likely to curb the movement’s development. Yet, in the expansion stage of the Takfirist movement, organizational strength and framing process appear to play more important roles, and any attempt to control the movement by narrowing political opportunities at this stage may be more costly and less effective.

Second, along with the increasing Islam phobia, many countries have been trying to weaken Islamic practice for the sake of counter terrorism. However, the case of Ansar al-sharia suggests that religious frames cannot necessarily be transferred to high mobilization capacity. The implication is that if the regime overlooks social grievances, national governance capacity, and regime legitimacy, but simply ban women from wearing veils and men from growing beards, the effects of counter-terrorism are unlikely to be significant.

Lastly, as we can see in the case of Ansar al-Sharia, the group has already developed networks with international terrorist groups. Thus, even if the government of Tunisia tightens its control on terrorist groups, many militants can still survive and thrive by joining the terrorists in other countries. In this context, the mission of counter-terrorism in a single country like Tunisia needs transnational collaboration, such as the collaboration in intelligence sharing.

All in all, Tunisia is still undergoing a fragile political transition period. The rise of the Takfirist movement not only poses threat to national security, but also hinders the construction of Tunisians’ national and state identity as it denies democracy and advocates violent activities [63]. The Tunisian government needs to improve domestic security environment by enhancing the state’s capacity, solving specific socio-economic problems, and strengthening international counterterrorism co-operation.

Although the current Tunisian government becomes much less tolerant of Takfirist ideologies and activities than the transition government led by Ennahda, recent counterterrorism policies proposed by Beji Caid Essebsi seem to have gone to the other extreme by suppressing religion, increasing the police’s privileges, and abusing private rights [64]. Rather than helping improve the country’s security, these policies may be employed by the Takfirist movement to mobilize citizens under the slogan of fighting for religious freedom. Today, how to maintain a balance between freedom and security, and improve the country’s security without reaching beyond the boundaries of state power, are important challenges confronting Tunisia’s security management.

References

- (2017) The paper is translated from the Chinese version published in Arab world studies.

- Samuel PH (1991) The third wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London, UK.

- http://soufangroup.com/wp-ccontent/uploads/2015/12/TSG_ ForeignFightersUpdate3.pdf.

- http://foreignfighters.csis.org/tunisia/tunisian-fighters-in-history. html.

- Yaroslav T (2016) How Tunisia became a top source of is recruits. The Wall Street Journal.

- (2014) The salafist struggle. Economist.

- Chengzhang B (2013) Salafism since the Upheavals of the middle east. Arab World Studies p. 110.

- International Crisis Group (2012) Tentative jihad: syrian fundamentalist opposition. Middle East Report 131: 135.

- Laura G (2013) Ennahda islamists and the test of government in Tunisia. The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs 48(4): 34.

- Chengzhang B (2013) p. 112.

- Edmund R and Marie CR (2016) Jihad instead of democracy: Tunisia’s marginalised youth and islamist terrorism. The Globalisation of Terrorism 1: 81

- http://www.criticalthreats.org/al-qaeda/basics/takfirism

- Michael M (2011) Urban poverty and support for islamist terror: Survey results of muslims in fourteen countries. Journal of Peace Research 48(1): 35-47.

- Daniel EA (2013) Why book haram exists: the relative deprivation perspective. African Conflict and Peace Building Review 3(1): 144-157.

- Assaf M (2008) The salafi-jihad as a religious ideology. CTC Sentinel 1(3).

- Dina Al Raffie (2012) Whose hearts and minds? narratives and counternarratives of salafi jihadism. Journal of Terrorism Research 3(2).

- http://www.reuters.com/article/us-tunisia-attack-gunmenspecialreport- idUSKBN0O205F20150517.

- http://www.smh.com.au/world/tunis-gunman-loved-life-says-brother- 20150321-1m4qyw.html

- Robert K Merton, Leonard Broom, Leonard S Cottrell (1959) Sociology today. New York, USA, pp. 429-441.

- Gerhard L (1954) Status crystallization: A non-vertical dimension of social status. American Sociological pp. 405-413.

- Graeme C, Ian Welsh (2011) Social movements: The Key Concepts, Routledge, London, UK, p. 7.

- Doug Mc Adam. p. 24.

- Graeme C, Ian Welsh (2011) Social movements: The Key Concepts, Routledge, London, UK, p. 136.

- Doug Mc Adam, John D McCarthy, Mayer N Zald (1996) Comparative perspectives on social movements. Cambridge University Press, New York, USA.

- Dell P, Donatella, Mario D (1999) Social movements: An introduction, cambridge: blackwell. In: Gay WS (Ed.), Manufacturing militance: workers’ movements in Brazil and South Africa, 1970-1985, Berkeley: University of California Press, USA, p. 43.

- Doug McAdam, John D McCarthy, Mayer N Zald, Aldon D Morris, Carol McClurg M (1992) Frontiers in social movement theory, Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

- David A Snow, Robert B (1988) Ideology, Frame resonance, and participant mobilization. In: Bert K, Hanspeter K, Sidney T (Eds.), From Structure to Action: Comparing movement participation across cultures, International Social Movement Research, , JAI Press, Grenwich, UK, pp. 197-218.

- Banu E (2010) The mobilization of political islam in Turkey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, USA, pp. 1-36.

- Doug McAdam (1995) Initiator and spin-off movements: diffusion processes in protest cycles. In: Mark Traugott (Ed.), Repertoires and Cycles of Collective Action, Duke University Press, Durham, pp. 220-222.

- (1989) Al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya was formed in 1960 In 1981, the organization established a political party called The Movement of Islamic Tendency which was renamed as Ennahda in 1989.

- Stefano MT, Fabio M, Francesco C (2012) Salafism in Tunisia: Challenges and opportunities for demcoratization. Middle East Policy 19(4): 142.

- http://emadshahin.com/eshahin2/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ Secularism-Tunisia-Final.pdf

- Mehdi M (2012) Tunisia: The radicalisation of religious policy. In islamist radicalisation in north Africa: politics and process, George Joffé, Routledge, London and New York, USA, pp. 57-60.

- https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/tunisian-jihadism-after-the-soussemassacre

- Aaron YZ (2012) Jihadi soft power in Tunisia: ansar al-shariah’s convoy provides aid to the town of haydrah in west central Tunisia, al-Wasat, the Muslim World, Radicalization, Terrorism, and Islamist Ideology.

- Said R (2010) Menace grandissanted’ aqim, el watan.

- Alaya A (2009) The islamists in Tunisia between confrontation and participation: 1980-2008. The Journal of North African Studies 14(2): 265-266.

- http://www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/tunisias-salafist-tangleand- the-long-road-to-stability

- Monica M (2013) Youth politics and Tunisian salafism: understanding the jihadi current. Mediterranean Politics 18(1): 112-114.

- http://www.merip.org/mero/mero043011

- Tom H (2013) Ennahda’s religious policies split Tunisia’s ruling party. Reuters.

- Christine P (2015) Tunisian Salafism: The rise and fall of ansar al-sharia.

- Laura Guazzone, pp. 36-39.

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/07/31/tunisia-counterterror-lawendangers- rights

- Sarah M (2015) Tunisia’s ineffective counterterrorism law.

- Stefano MT, Fabio M, Francesco C pp. 140-154.

- Daveed G, Bridget M, Kathleen S, Aaron YZ (2018) Meeting Tunisia’s ansar al-sharia, Foreign Policy p. 5.

- Gartenstein R (2013) Ansar al-Sharia Tunisia’s long game: dawa, hisba, and jihad. ICCT Research Paper p. 7.

- Uqba bin Nafi was a famous general of the Umayyad dynasty in the 7th century. The militant camp established by AQIM and Ansar al-Sharia was named after this general.

- Daveed GR, Bridget M, Kathleen S (2013) Possibles connexions entre réseaux terroristes et de contrebande. TAP, pp. 7-8.

- Al Qaïda (2012) menace-t-elle vraiment la Tunisie? Business News.

- https://news.siteintelgroup.com/Jihadist-News/alleged-group-jund-alkhilafah- in-tunisia-pledges-to-is.html

- Thomas J (2014) Ansar al sharia Tunisia leader says gains in Iraq should be cause for jihadist reconciliation. The Long War Journal.

- Aaron Z (2012) Missionary at home, jihadist abroad: a profile of Tunisia’s abu ayyad the amir of ansar al-shari’ah”. Jamestown foundation 3(4): 9.

- https://justpaste.it/geo5

- Fabio M (2013) Salafism in Tunisia: an interview with a member of ansar al-sharia. jadaliyya.

- Noureddine M (2016) Social media as a new identity battleground: the cultural comeback in Tunisia after the revolution of 14 January 2011. In: Noha M, Khalil R (Eds.), Political islam and global media: the boundaries of religious identity. Oxon: Routledge, London, UK, p. 40.

- Aaron YZ (2013) Meeting Tunisia’s ansar al-sharia. Foreign Policy.

- Daveed GR, Bridget M, Kathleen S p. 9.

- Thomas J (2013) Ansar al sharia Tunisia calls for islamist solution to political crisis. The Long War Journal.

- Zeineb M (2015) Tunisia’s activists declare war on ‘reconciliation law. Tunisia Live.

- S J (2014) The salafist struggle. Economist.

- (2012) Tunisie le cancer salafiste. La Jeune Afrique 52: 2683.

© 2018 Chuchu Zhang. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)