- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Remote Rehabilitation: A Solution to Overloaded & Scarce Health Care Systems

Karla Muñoz Esquivel1*, Elina Nevala3, Antti Alamäki3, Joan Condell1, Daniel Kelly1, Richard Davies2, David Heaney1, Anna Nordström4, Markus Åkerlund Larsson4, Daniel Nilsson4, John Barton5 and Salvatore Tedesco5

1 Magee Campus, Ulster University, UK

2 Jordanstown Campus, Ulster University, UK

3 Research, Development and Innovation activities (RDI) & Physiotherapy Education, Karelia University of Applied Sciences, Finland

4 Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University, Sweden and School of Sport Sciences, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

5 Tyndall National Institute, University College Cork, Ireland

*Corresponding author:Karla Muñoz Esquivel, Ulster University, ISRC, Magee Campus, Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland, UK, BT487JL

Submission: July 09, 2018;Published: August 27, 2018

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 1 Issue 1

Abstract:

The population across Northern Europe is aging. Coupled with socio-economic challenges, health care systems are at risk of overloading and incurring unsustainable high costs. Rehabilitation services are used disproportionately by older people. One solution pertinent to rural areas is to change the model of rehabilitation to incorporate new technologies. This has the potential to free resources and reduce costs. However, implementation is challenging. In the Northern Periphery and Artic Programme (NPA), the Smart sensor Devices for rehabilitation and Connected health (SENDoc) project [1] is focused on introducing wearable sensor systems among elderly communities to support their rehabilitation. It is important to understand the context into which change is introduced. Therefore, an overview of the current state of health care systems in the four partner countries is presented, defining the concept of rehabilitation and how remote rehabilitation is currently delivered. Advantages (e.g. enhanced outcomes, less cost and enhanced patient engagement), and disadvantages of remote rehabilitation (e.g. complexity involved in the use of technology, design and safety issues) are discussed. It is concluded that the key advantage of remote rehabilitation is the potential to support change in patient behaviour, empowering active participation and living independently, with less need to travel for face-to-face sessions. Remote rehabilitation can make enhance quality of health care service delivery.

However, all relevant stakeholders including medical staff and patients should be included in the design of the technology employed with a focus on simplicity, usability and robustness. Compliance with Security and the new GDPR regulation will be key to supporting remote rehabilitation. In addition, the diversity of available platforms and devices must also be supported to ensure interoperability. Finally, remote rehabilitation needs to be further validated in practice. Attempts to implement and sustain change should be cognisant of local and current organization of health care and of existing enablers and barriers.

Keywords: Elder; Health care; Remote rehabilitation; SENDoc; Wearable sensor technologies

Abbreviations: COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; EU: European Union; GAS: Goal Attainment Scaling; GP: General Practitioner; HCP: Home Care Package; HSC: Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland; ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; ICO: Information Commissioner’s Office; IGA: Information Governance Alliance; ITTS: Implementing Transnational Telemedicine Solutions; KELA: The Social Insurance Institution of Finland; MCRN: Managed Clinical Rehabilitation Networks; NCPRM: National Clinical Programme for Rehabilitation Medicine; NHS: National Health Service; NPA: Northern Periphery and Artic Programme; RI: Rehabilitation International; SENDoc: Smart Sensor Devices for rehabilitation and Connected health; UCC: University College Cork; UK: United Kingdom; VLL: Västerbottens Läns Landsting; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Increased life expectancy and decreasing childbirth are changing aging demographics in several countries. In 2016 people aged over 65 years in each of the partner countries involved in the SENDoc project were as follows: Finland 20.5%, Sweden 19.8%, UK 17.9%, Ireland 13.2%, EU 19.2%. At a regional level within partner countries the percentage of population over 65 years old was reported as: North - Karelia 24.3%, Västerbotten 20.8%, Northern Ireland 12% and Ireland 19.1% [2]. This increasing elderly population, together with long distances to social and health care services (including rehabilitation/therapies) for those living in rural areas cause severe socio-economic challenges to health care systems. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a cost-effective and user-centered solution for the remote health care and rehabilitation of the elderly in rural areas. Cultural and infrastructure differences between countries causes the need for tailored solutions, when considering regional health and rehabilitation services [3]. In comparison, 20% of US of patients live in rural areas, but only 9% of physicians work there. In rural areas the outcomes are that inhabitants have to travel 2 to 3 times further to see their physician/specialist [4], accessing services is more difficult, communities experience a higher level of isolation, some specialist services are unviable owed to the small groups of patients and it is more difficult to recruit people.

In the UK, in 2016, approximately 24% of the people aged 65 years or older live predominantly in rural areas [5]. This figure is projected to increase by an average of 20% by 2024. Currently it is estimated that 1 in 8 older people are not receiving the help they need which accounts for around 1.2 million elderly people in the UK. There are many contributing factors such as an increasing demand in consultations that cannot be fulfilled by the current number of general practitioners or nurses; deterioration of the health of carers for lacking of breaks; the gradual reduction of beds in hospitals owed to the time that patients spend in it (decisions to admit patients increase by 16% while the available beds fell by 8% from the last quarter of 2010/11 to the last quarter 2016/17); increased number of people treated for cancer or mental health care issues that have to wait longer for treatment; and patients do not have easy access to services close to home [6]. The NPA SENDoc project aims to introduce wearable sensors in elderly populations to support remote rehabilitation and how services are expected to adapt in the near future. This paper focuses on how the health care services operate and will be expected to perform in all locations in the NPA SENDoc project and aims to identify enablers and withholders which should be considered when introducing remote rehabilitation technology for these regions.

Remote rehabilitation, monitoring and measuring exercises might help to solve the problems related to patient access to rehabilitation, therapies or physicians. Although smart sensor devices have shown to be accurate and have clinical utility and usage, they continue to be underused and underutilized in health care. This monitoring could extend or replace routine outpatient care or rehab process [7]. Remote rehabilitation is one way of digitalizing services. Other examples of digitalizing health care services are creating electronic health records and m-health (practicing medicine by using portable diagnostic devices). Remote rehabilitation is referred to by many different terms, such as net therapy, telerehabilitation, virtual rehabilitation or mobile rehabilitation. All of these terms are too narrow to describe remote rehabilitation in general. Remote rehabilitation is the goal-oriented use of various remote technology applications in rehabilitation, for example phone, mobile phone, computer, computer sharing and television applications. Remote rehabilitation is controlled and followed by professionals and it has a clear goal, from beginning to end, as with other rehabilitation [8]. Remote rehabilitation improves cost, attains patient engagement and enhances outcomes (e.g. safety and quality of care and accelerates advances in medical practice). This work presents how remote rehabilitation is being viewed and approached in all four partner countries.

Enabling remote monitoring with wearable systems usually involves three key aspects: hardware for sensing and data collection of physiology and movement; communication hardware and software to transfer the data to a remote center; and dataanalysis for clinically-relevant information to be extracted [4]. The implementation of remote rehabilitation involves dealing with ethical, legal, economic, political and safety challenges, which are briefly discussed in this review. Problems of usability and acceptability, data protection and other related technology problems that also affect remote rehabilitation are examined. This is followed by a brief discussion and recapitulation of the most relevant aspects of this research. Finally, the conclusion of this review is presented.

Structure of Health Care Systems in SENDoc

To change existing rehabilitation processes, it is essential to understand the current health care and rehabilitation structures. These structures and processes vary in each country where the SENDoc project is taking place. Other factors such as distance from services and staff also have an impact in these processes.

Health care in Finland

The Social and health care system and legislation in Finland is going through the biggest change since 1970. During this ongoing process the organization and financiering of different rehabilitation processes are likely to change in the near future.

Current legislation divides social and health care into basic health care, specialized health care and social services. All of these are financed by the tax payer through municipalities and the government. Services are either free or require a small contribution from patients and customers. They all organize various rehabilitation processes and under those different therapies (physical, occupational, speech, psycho, etc.).

Private social and health care consists of various organizations (e.g. hospitals, care homes, occupational health care, rehab centers, medical clinics, dentist clinics, therapists, clinics)., who are financed by insurance companies, patients/customers, industry etc. Patients/customers are entitled to compensation of expenses from the Social Insurance Institute of Finland.

In 2014, more than 20% of individuals, aged over 75 years old, needed regular homecare, long-term care or health care ward care in Finland. In the 2010-decade, the number of people in regular home care has surpassed the number of patients in service homes or health care institutions. It is estimated that the need for homes and intense care service homes will increase by 30,000 in 2030 when compared to the levels observed in 2014 [3].

Siun sote: The joint municipal authority of social and health care in North Karelia

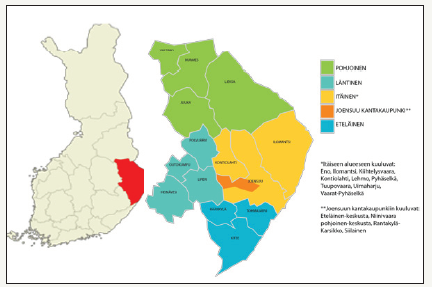

In North Karelia, Siun sote (The Joint Municipal Authority of Social and Health Care) organizes the public social and health care services. In practice, this means that specialized medical care, primary health care and social services are united. There are 7,000 employees in Siun sote and altogether there are about 170,000 inhabitants in the area. In public health care approximately 170 workers are employed as therapy rehab staff-in medical rehabilitation-(occupational therapists, physiotherapists and assistant physiotherapists). This staff work together with the 115 doctors based in the health care centers and in the special health care area. These doctors work directly or in co-operation with rehabilitation staff. Figure 1 shows the North Karelia and Siun Sote areas.

Figure 1:On the left, picture shows North Karelia, Finland in red. On the right, picture shows the area of Siun sote.

In North Karelia, the rural area is considered to start immediately outside the grid pattern of Joensuu (5 km). Long distances have a significant impact on the organization of the services. In North- Karelia, in 2015, 33% of people lived 30 - 90 minutes driving distance from the hospital (mean distance to hospital is 39.9 km). In town areas, health care facilities are more accessible, but most of them are located in the countryside - in population centers. About one third of facilities are located in areas where private car use is needed.

In the near future it is likely that Finland moves towards using new technologies - including health technologies, sensor technologies, digital media, mobile technology and digital services, since these have the potential to bulk interactions between health care personnel and customers/patients [9,10]. For example, the development of new technology - logistics, digital and other new service processes - will cause a decrease in services, which are location dependent. For example, the number of health centers can be reduced to nearly half of the current level, especially in Southern and Central Finland [11].

Health care in Sweden

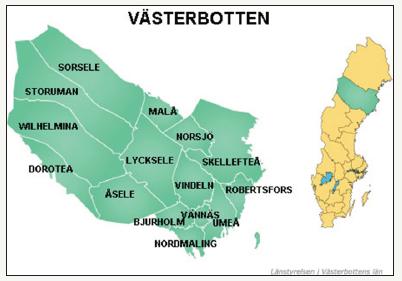

Västerbotten County Council (VLL) with 10,000 employees is responsible for conducting health care, dental care, and education/ research. VLL currently conducts highly specialized care for the 4 northernmost counties in Sweden. Northern Health Region comprises half of Sweden’s area and has approximately 892,000 inhabitants. In 2017 the region could provide 936 hospital beds [12]. (Figure 2) shows the Västerbotten area.

Figure 2:On the left is show Västerbotten area in detail and on the right it is indicated where Västerbotten is located in Sweden

What the country council at Västerbotten produces during a year is [12]:

a. 51,000 inward patients are produced during a year

b. 30,000 operations

c. 336,000 visits to the doctor at the health care unit

d. 218,000 medical visits to the health center

e. 903,000 health care treatments

f. 318,000 visits to the dentist

g. These amount 1,856,000 (Figure 3).

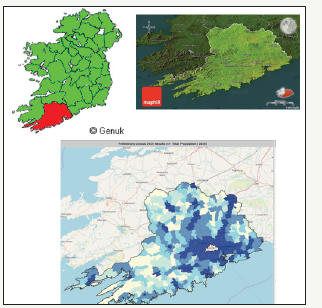

Figure 3:On the top left, the picture shows the location of County Cork with respect to Ireland in red, on the top right picture is shown County Cork and on the bottom picture is shown the population density of County Cork through colours (less populated to more populated areas from lighter to darker tones respectively).

In 2016, the government set out a vision of Sweden as world leader in e-health by 2025. The strategy involves: 1) coordination and communication among health care stakeholders; 2) development of common concepts in the field; 3) implementation of standards for health information exchange; and 4) creation of national drug lists that assist health care professionals in efforts to improve patient safety [13].

Health care in Ireland

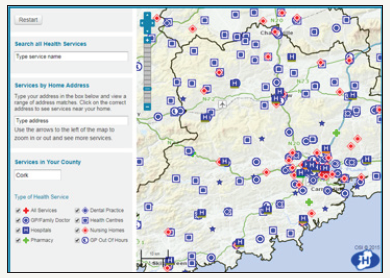

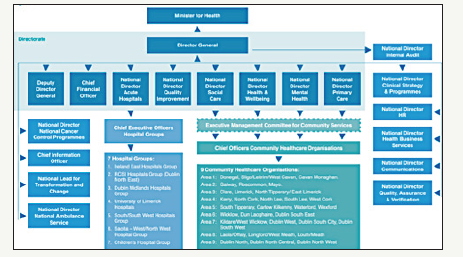

In Ireland, the Government, Minister for Health and Department of Health are responsible for the development of health policy. The Health Service Executive (HSE) is the national body responsible for strategic planning, implementation and management of health and social services. Policy and guidelines are developed for national use to ensure quality in service, however the implementation of these at local level is open to interpretation and is dependent on local area budgets. The structure of the HSE can be seen in Figure 4. The HSE is divided up into four regions. Two of these regions, HSE South and HSE West, include counties within the Interreg Northern Periphery and Artic Region. The overall population of the counties within the Northern Periphery and Artic Region is 1.6 million, with approximately 200,000 people aged over 65.

Figure 4:Health care services distribution in County Cork.

According to the HSE:

A. Acute Hospitals work closely with the hospitals groups in Figure 4 to deliver hospital services throughout Ireland, including inpatient care, emergency care, maternity, diagnostic and outpatient services.

B. Primary Care is all of the health or social care services that can be found in the community outside of the hospital/ acute setting. A Primary Care Team (PCT) may be comprised of GPs and GP nurses, Public Health Nurses (PHNs), Occupational Therapists, Physiotherapists and home help/support staff. The PCT also links with speech and language therapy, dieticians, mental health services, social workers, psychologists, podiatrists, dental and ophthalmic services. GPs out of hours services are also part of primary care.

C. Social Care supports the needs of older people and people with disabilities to live at home, independently within their community. Some of the services for older people include home care packages [14] older person primary care and community services [15], benefits and financial entitlements, nursing home support scheme [16] and residential care [17].

Figure 5:Irish Health Service Executive Organisational Structure

Social and Continuing Care in Ireland is provided to meet physical and/or mental health needs arising from disability, frailty, accident or illness, and can be provided over an extended period of time in a multitude of settings, including a person’s home, day hospitals, health centres as well as nursing homes and hospices. Social and Continuing Care in Ireland is currently fragmented, differs across regions and is lacking integration with other health care services. A number of new Integrated Care Programmes (Figure 5) are currently under development and are designed to more closely integrate health and social care delivery. However, this development is still at a very early stage.

In Ireland, free primary care and medications are available at the point of care for those deemed eligible based on their socioeconomic status. These individuals are registered to a single GP. Those who are responsible for paying for their own health care largely tend to be registered to a single GP, but this may not necessarily be the case. However, as of 2015, all those over 70 are entitled to free GP care and can apply for a GP Visit Card.

Demographics and elder in Ireland

County Cork is the largest and southernmost county of Ireland. It is situated in the province of Munster and named after the city of Cork, The second largest city of Ireland. It is the largest county in Ireland by land area, and the largest of Munster’s 6 counties by population and area. The population of the entire county is 542,196, making it the state’s second most populous county and the third most populous county on the island of Ireland. With an area of 7,500km2, this gives a population density of just over 72 people per km2. However, as the population distribution taken from the 2016 census shows in Figure 3, this is heavily skewed towards urban areas, primarily Cork city, and large parts of the county are very rural and relatively remote from health services as can be seen in Figure 4.

In Ireland, the number of people aged 65 and over grows by 20,000 each year. Ireland’s ageing population growth is much higher than the EU average. Between 2011 and 2025, the over-65 population will increase by approximately 54%, while the number of over-85s will double. A 2013 Census report by the Central Statistics Office (CSO) projects that the number of people aged 65 and over in Ireland will increase from 532,000 in 2011 to between 850,000 and 860,700 by 2026 and will be close to 1.4 million by 2046. A more dramatic increase is expected in the number of people aged 80 and over, increasing from 128,000 in 2011 to between 464,000 and 470,000 in 2046. This will result in a significant change in the structure of the Irish population. From 2006 to 2026, within the 65 and over age group, the dependency ratio is expected to increase from 16.4% to 25.1% for Ireland. The health statistics released by the Irish Department of Health indicate that average life expectancy of the Irish population has grown by 10 years over the past 50 years [18] and is now above the EU average. Life expectancy for men is 79.6 years, while it is 83.4 years for women [19]. Healthy life years at age 65 is 11 for men and 12 for women.

Relevant National Policies and Programmes

Recent years have seen a number of developments within the Irish health care context, with the overall aim of improving the Irish health system and patient care. Some programmes/policies relevant to the rehabilitation and treatment of elder include:

A. Slainte Care [20]. In June 2016, the Dáil (Irish Parliament) established the Committee on the Future of Health care with the goal of achieving cross-party, political agreement on the future direction of the health service and devising a tenyear plan for reform. The report into SlainteCare was published in May 2017

B. The National Clinical Programme for Older People [21]. It supports older people to live in the community, independently and with dignity.

C. The National Clinical Programme for Rehabilitation Medicine (NCPRM) [22]. Its objective is to describe a framework whereby the ability and societal participation of those affected by complex, life-altering conditions can be maximized by early, timely and life-long intermittent access to specialist rehabilitation.

D. Ireland’s e-Health Strategy [23]. Established in 2013, this strategy outlines a set of objectives to be achieved in implementing e-health in Ireland and provides a roadmap to achieve these.

E. Integrated Care Programmes [24]. Launched in 2014, it aims to join up health and social care, focusing on programmes for chronic disease management, older people, patient flow, maternity and children.

F. There are a number of policies on chronic disease management. However, these focus on single disease treatment, for example, the Policy Framework for the Management of Chronic Diseases in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) [25].

Health care in UK

The National Health Service (NHS) is the collective name given to the public health services in the United Kingdom. It is comprised of the NHS in England, NHS Wales, NHS Scotland and Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland. The NHS is based on the founding principle that services would be comprehensive, universal and free at the point of delivery. Each of the 4 country service systems operate independently and are politically accountable to their respective countries’ government.

Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland (HSC)

The HSC is the publicly funded service which provides public health and other social care services in Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland Executive, through the Department of Health, is responsible for the funding of the HSC. As well as providing health services, the HSC also provides social care services such as home care services, family and children services, day care services and social work services. As well as being responsible for Health and Social Care, the Department of Health is also responsible for Public Health and Public Safety.

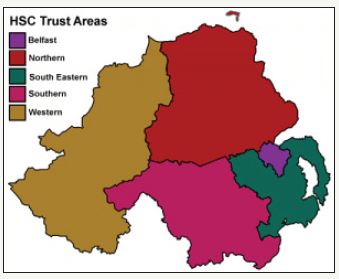

Figure 6:Organization of NHS into 5 regions.

The HSC is organized into 5 regions (Figure 6) with each region having a statutory body responsible for the management of staff, health and social care services on the ground. These statutory bodies are known as Trusts and have control of their own budgets. Four of the five trusts, with a total population of 1.5 million, reside within the Interreg Northern Periphery and Artic Region.

As it was discussed earlier, there is a growing demand for health care services and currently people are not attaining the care that they require in the UK. Research, of particular relevance to this work, shows that 1 in 8 older people do not receive the care that they require in the UK [6]. The medical staff and resources (such as beds) are not available to cope with this demand appropriately. As a result, the waiting time for treatment is longer and some of the treatments are not near where the people actually live [6]. Therefore, there are currently efforts in the UK to decentralize health care services and move towards eHealth and digitalization of health care services.

In 2013, the secretary of State of Health in the UK, Jeremy Hunt, challenged the NHS to go paperless by 2018 to derive benefit from the information revolution [26]. This is to close three gaps identified: care and quality, funding and efficiency and health and wellbeing. The approach of NHS for digitalization in previous years to 2013, resulted in fragmentation of NHS and systems not working together, while on the other hand over-centralization has led to systems that do not meet local needs. Therefore, national bodies are now providing the national standards and electronic-glue for attaining interoperability and enabling different parts to work together at the same time enabling local partners to make their own choices according to their local health care needs. This was expanded into an NHS five year forward view by 2020 to sustain the digital transformation. The National Information board was set up to lead the transformation of patient’s experience of health care.

Perspectives of remote rehabilitation in SENDoc and its advantages

To define remote rehabilitation, it is important to first define the rehabilitation concept in general and then what we mean by “remote rehabilitation”. This section also presents the investigation conducted about the definitions of these concepts in each SENDoc’s area.

Rehabilitation International [27]. (RI Global) defines rehabilitation as: “regaining skills, abilities, or knowledge that may have been lost or compromised as a result of acquiring a disability or due to a change in one’s disability or circumstances.”

World Health Organization (WHO) [28]. Defines rehabilitation as: “consisting of a set of measures that assist individuals who experience, or are likely to experience, disability to achieve, and maintain optimal functioning in interaction with their environment. Rehabilitation thus maximizes people’s ability to live, work and learn to their best potential. Evidence also suggests that rehabilitation can reduce the functional difficulties associated with ageing and improve quality of life.”

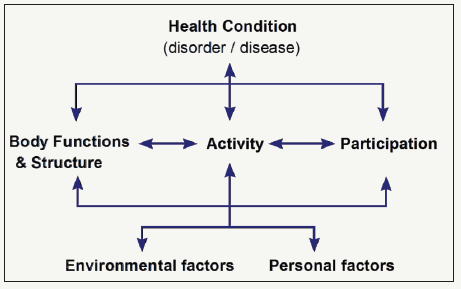

The International Classification of Functioning, disability and health (ICF) is a scientific, operational basis for describing, understanding and studying health and health-related states, its outcomes and its determinants. ICF offers a standard language and conceptual basis for the definition and measurement of disability (and it provides classifications and codes). The ICF provides a multiperspective, a bio-psycho-social approach, which is reflected in the multidimensional model classifying functioning and disability. There is not an explicit or implicit distinction between different health conditions. The health and health-related states associated with any health condition can be described using ICF. Adopting an ICF-mindset in the use of wearable sensors (for measurements and analyses) and combining it with other taxonomies for equipment and methods, may assist different professionals to achieve an enhanced understanding of each other and may provide more specific and sensitive results in that direction [29].

ICF -classification is used as basis for scientific work and education of social and health care in Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway). For example, in Sweden they have developed an ICF -based instrument Behov Av Stöd (BAS) for elderly’s social services, and in Denmark ICF-based needs assessment is used in adult social work [30]. ICF is a framework that conceptualizes functioning as a “dynamic interaction between a person`s health condition, environmental factors and personal factors. It integrates the major models of disability - the medical model and the social model - as a “bio-psycho-social synthesis”. ICF clarifies that we cannot infer participation in everyday life from medical diagnosis alone [29]. Figure 7 shows the interaction between components in the ICF model.

Figure 7:The ICF Model: Interaction between ICF components [29].

Rehabilitation in Finland

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland [31] published its proposals related to how an equal, cost-effective and controlled rehabilitation system is developed, which supports and strengthens rehabilitation in all situations of life. In these proposals from the rehabilitation reform committee [32] rehabilitation was defined as a process that aims at functional and working ability. Rehabilitation is based on the patient’s/client’s needs and goals.

It is essential to support the patient’s/client’s own activity. The purpose of rehabilitation is also to support close relatives and to develop an operating environment to improve the patient/client’s performance. In Finland, patients are directed to rehab processes through various ways, in some cases by self-referral/direct access or by referral of different professionals.

Rehabilitation is a process that requires the patient’s/clients’ commitment and timely rehabilitation measures. Changes in functional ability require a change in interaction between the individual and the environment. In the rehabilitation process, interventions are targeted and implemented, not only for a patient/ client, but also for their environment and people in it [33].

Rehabilitation refers to an activity where the patient/client defines relevant and realistic goals. To achieve these goals, the means are designed with experts/specialists and implemented largely independently or supported by the local environment. When human activity is impaired or threatened, the activity of human resources has to be considered in every situation in rehabilitation. The patient/client has changed from the object of the measures to be an active and equal participant. Rehabilitation is a multidisciplinary entity, regardless of whether medical, social, educational or vocational rehabilitation is concerned [33].

The concept of Rehabilitation in Finland includes:

A. Medical rehabilitation (includes rehabilitation of elderly people-SENDoc focus) and Medical rehabilitation for people with severe disabilities

B. Rehabilitative work experience

C. Vocational rehabilitation

D. Rehabilitative psychotherapy (might be included in rehabilitation of elderly people)

E. Social rehabilitation (might be included in rehabilitation of elderly people)

F. Rehabilitation in the event of workplace or traffic accidents

G. Rehabilitation under the Military Injuries Act

H. Disability services (might be included in rehabilitation of elderly people)

I. Special education in comprehensive schools

J. Vocational special needs education, The Labor Administration`s vocational rehabilitation and Discretionary rehabilitation [32]

Depending on the rehabilitation area or need, independent professionals contribute and decide their own activities in the rehabilitation processes and if needed, in co-operation with multiprofessional teams. A rehabilitation service can include parts of different areas, for example therapies (physio, speech, psycho etc.), social rehabilitation and educational rehabilitation.

Home/Remote Rehabilitation in Finland

In Finland there is no general definition of home rehabilitation. Each organization and stakeholder use it in their own way, based on their needs. Home rehabilitation covers a wide range of care and rehabilitation services, but the main point is that they are implemented at least in part in people`s own houses or homelike conditions [34]. In Siun sote (North Karelia) home-based rehabilitation has been remodeled and unified since the beginning of 2017. It is based on ICF-classification and in GAS (Goal Attainment Scaling) assessment. GAS is a client-oriented tool for identifying the goals of a patient/client and achieving goals can be viewed at the individual or group level by using statistical methods. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland (KELA) uses GAS [35].

One example of reorganization of the rehabilitation system in general and home-based rehabilitation in Finland is South Karelia Social and Health Care District (Eksote). They have developed it since 2010. A new rehabilitation system was introduced in 2014: a rehabilitation hospital was established, a large number (over 500) of ward beds in public health care were removed and rehabilitation resources were added to home-based rehabilitation. Development activities included several projects that aimed to improve functional capacity of an elderly person, so that the patient is able to live at home as long as possible [36].

Key issues in this development have been: creating a common strategy and vision, developing the skills of nursing staff, attaining the engagement of nursing staff, common agreed approaches and common agreed action models. It was decided to focus heavily on the early stage of elderly services. Home-based rehabilitation includes three models: Early intervention and health promotion, rehabilitation which supports home care services and multidisciplinary home-based rehabilitation [36]. Positive changes have already been achieved through reorganization. One year after the rehabilitation period, 94% of people aged over 75- lived at home (2016) and the target level in Finland is 91-92% [37]. The following aim is to make home care and nursing “unnecessary”. The concrete aim is that less than 10% of people aged over 75 would need regular home care.

In Finland remote rehabilitation has been developed in various development projects and experiments since 2000, but today its regular use is still low. There are few research publications on remote rehabilitation. The main developing target group has been older people [8]. Remote rehabilitation can be applied quite widely to rehabilitation, assessment, home exercises, family counseling, monitoring of functional ability and well-being, collaboration meetings and professional co-operation [38], but the slowness of administrative and regulatory development has limited the introduction of remote services [39].

The Age Institute in Finland made a survey about the experiences of elderly people with remote health exercising. They found 49 projects or places in Finland, where remote health exercise were implemented. Remote health exercising is transmitted in the form of a one-way video or using two-way “picture phone”. In one-way video, only the instructor can communicate in the direction of the participants. When using two-way technologies, both the instructor and the participants can communicate with each other. Videos can be a synchronous real-time broadcasts or recordings that can be shared by participants via online services or social media, such as YouTube. Four different approaches were found that differ in terms whether there is one-way or two-way interaction or whether elderly people are involved alone or in a group. Also, the group´s location varies: it can be in the same room with the instructor or via remote connection elsewhere [40].

According to this survey, remote health exercise was organized by institutions, municipalities, companies and organizations. Projects on educational institutions often formed the continuum of several projects, whereby development work can be done over many years. In Municipalities these projects were usually pilots. Financing of projects usually comes from an external funding body (e.g. EU, TEKES) and the municipality contributes costs with its labor input or self-financing share. When these projects end it´s problematic to find new sources of funding. Thus, after the pilot projects, remote health exercise usually ends. Possibilities for the elderly to pay for remote health exercises are not accessible according to the interviewees [40].

National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (Valvira) in Finland instructs and monitors on remote services and their use in social and health care. Remote services in health care means that the examination, diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, treatment decisions or recommendations of a patient are based on, for example, video or information transmitted via web or smartphone. The guidance applies both to public health care and to the private service provider where the health care service is provided to the patient via remote services.

Rehabilitation in Sweden

In Sweden a central take on the concept of rehabilitation for the elderly is “Everyday rehabilitation”. The concept is funded on the vision and belief that supporting the elderly to live autonomously is the sustainable way to proceed both from an ethical and a resource perspective. This transforms the relationship between the care-giver and the care-taker into a dialogue - instead of medical care-production. It makes use of competences outside the medical care profession focused competences and includes a more holistic approach, such as cultural activities and social networking [41].

Home/Remote rehabilitation in Sweden

Since the year 2000 there has been a reduced number of care provided in care homes in Sweden to the advantages of supporting active aging - living lives at home maintained by increased focus on rehabilitation. A relative decline of numbers of elderly receiving care in institutions is partly described as individuals having more years of non-dependencies due to healthier choices and paired with rehabilitation, assistive technology and (re)enabling-design [42].

In Sweden the different municipalities are responsible for organizing home-based rehabilitation. This is a great responsibility and core concepts are fellowship, participation and sense of purpose and meaning-making. The concept of “vardagsrehabilitering” daily life-rehabilitation, rehabilitation of everyday activities has been explored from a research perspective and there are only a few scientific results that can be shared. On the other hand, there are many evidence-based results that are being referred to when taking out the direction of care and rehabilitation in many municipalities [43]. These perspectives and the shift of responsibilities for everyday rehabilitation and home-based rehabilitation - which has been given by the municipalities - is in some perspectives problematic. The level of competence in health care (among professionals working in the domain) is generally low. Also, elderly are seen as consumers of and in need of health care. These two aspects make this situation problematic and needs to be catered for [44,45].

Remote rehabilitation from the Swedish perspective is not an established term. Rehabilitation in general is managed both in situ at a rehabilitation center at health-care facilities and similar and as well at home (or remote from the rehab center). With the use of technology, the in-situ rehabilitation term may in some cases be exchanged by the “remote rehabilitation” term and then words such as e-health or digitalization within the health domain are more current [46,47].

In Sweden the ICF-classification is mainly a recommendation and used in research and comparative analysis. It has been discussed as a common platform for the development of the digital medical record. It has been included in education and guidance manuals and it has been developed in order to support the use of ICF in everyday practices. ICF is used today in many different contexts and for many different purposes worldwide. It can be used as a tool for statistical, research-related, clinical, social or educational purposes. It is applied not only in the health sector, but also in areas such as insurance companies, social insurance, working life, education, economics and the development of policies or legislation and environmental adjustments [48].

Rehabilitation in Ireland

Health services for older persons are delivered through a community-based approach with the aim of supporting older people to live in their own home and communities and, when needed, residential care is also provided. A key aim is to provide appropriate home supports and community-based services in order to maximize the potential of people remaining in their home and helping prevent unnecessary admissions to acute hospital facilities.

The national clinical programme for older people: The main goal of this programme is to support older people to live in the community, independently and with dignity. It is recognized that while many older people live healthy, independent lives, an increasing number suffer from frailty, multimorbidity and polypharmacy. One of the main policy documents emerging from this programme, published by the HSE and the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland, is the Specialist Geriatric Services Model of Care Part 1: Acute Service Provision (2012) [49]. This document states that the core responsibility of care for community-dwelling frail older people is with the GP and primary care team. It outlines the care pathways of older people through the health care system as well as the key stakeholders involved in their care. While the document primarily deals with older adult care in acute services, it states that Part 2 will address community care. However, as of yet, Part 2 has not been published.

The national clinical programme for rehabilitation medicine: The NCPRM model of care presents, in line with the National Policy and Strategy for the Provision of Neuro- Rehabilitation Services in Ireland 2011-2015, an outline for specialist rehabilitation services in Ireland. A hub and spoke model is proposed which includes a tertiary centre linking managed clinical rehabilitation networks (MCRN) each one serving populations of about 1m. The network will connect acute and postacute rehabilitation units, community specialist rehabilitation clinicians & community-based services in a formal way to allow delivery of coordinated rehabilitative care for patients.

Model of Care Key Recommendations:

A. Person-centered approach to service delivery

B. Equitable access to services

C. Three level model of service delivery across managed clinical rehabilitation networks (MCRN)

D. Development of appropriately resourced interdisciplinary inpatient, outpatient and community-based specialist rehabilitation teams across Ireland supported by education and training

E. Development of systems to facilitate measurement and data collection

However, as of this date (March 2018), the final draft model of care for the National Clinical Programme for Rehabilitation Medicine is currently advancing through the approval process following an extended period of consultation which ended in July 2016.

Home-based and remote rehabilitation in Ireland

The use of technology to facilitate rehabilitation in the elderly is extremely limited within the HSE. Overall, the HSE is behind its EU counterparts the usage of general ICT within the health care system. Ireland’s national health ICT spends 0.85% of the total health care budget relative to the EU range of 2-3%.

In early 2015, the formulation of a strategy to deliver eHealth to the HSE began. An eHealth strategy [50] has now been published which sets out how eHealth could benefit the Irish health care delivery system and a proposed roadmap of how eHealth can be implemented within an outcomes-based delivery system. One of the key principles of this strategy is a patient-centered approach with consideration for mental health, disability, children and aging.

However, though tele-health and tele-medicine is mentioned in a number of places, there is not any mention of rehabilitation in the entire document. There are many sentences and phrases such as “ICT systems such as electronic prescribing and tele-health will directly improve patient services allowing chronic disease to be managed in a more patient centered environment at community level including in patient’s homes”. However, no specific actions or steps are detailed.

One of the few examples of remote rehabilitation was a case study performed by National University Ireland, Galway, as part of the Implementing Transnational Telemedicine Solutions project (ITTS) [51]. ITTS, which completed in 2014, was part-funded by the European Union Northern Periphery Programme 2007-2013. The case study on Remote Exercise Classes for Rehabilitation was led by the University of Aberdeen, Scotland with a technology solution using internet-based Video Conferencing enabling patients to view their physiotherapist and other class members at the same time. and take part from either their own home or in a local based setting. The Irish team implemented this service for the rehabilitation of COPD patients based in the North County Clare area of Mid-West Ireland.

The home rehabilitation in Ireland receives the name Home Care Package (HCP). This is offered in Ireland to old people who live in the communities and are in-patients at critical hospitals or are at risk of admission to long-term care. Also, this package is offered to old people who were accepted into long-term care, but with support can return to the community. In this case individual and family needs are assessed and if more than 5 hours of home help are needed, people can apply for it. Services can be provided by non-HSE and HSE providers and can also be private or voluntary. Packages may include nurses, physiotherapy or occupational therapy, respite care, aids or appliances [52].

Rehabilitation in UK

Rehabilitation in the UK is defined as the action required to build new capabilities and further capacity in people to improve their quality of life. The UK’s overall vision for rehabilitation is that “Rehabilitation will be key to every episode of care”, with the aim of maximizing mental and physical health as well as independence (self-care and self-manage) and occupation (social inclusion) [53]. Rehabilitation can reduce health inequalities and make significant cost savings across the health and care systems. Rehabilitation is a holistic and individualized approach. It is centered on the patient’s needs - occupational requirements, views and experience - and those who are important to them. Rehabilitation is conducted focusing on setting measurable and achievable goals that are meaningful to the patient and that require ongoing assessment. It makes the patient an active participant in its care [54].

Rehabilitation in the UK includes a large spectrum of support that people may need at any age during their life such as developing skills for first time, recovering for unexpected illness, managing long-term conditions, self-managing conditions, recovering from major trauma, maintaining skills and independence and accessing advocacy. Rehabilitation may happen in three different settings: the primary care, the acute hospital and the community. As a result, the organizations, involved on meetings an individual’s suitable rehabilitation plan, include the NHS, independent and charitable organizations, user-led and community groups and local authorities [54].

Rehabilitation in the UK is focused on addressing the impact of problems in people such as physical or movement problems, sensory problems, cognitive or behavioral problems, communication problems, psychosocial and emotional problems, medical unexplained and mental health conditions. In the UK, rehabilitation is open to innovation which involves the creation and development of opportunities to use new approaches and technologies. However, this must be grounded in research and evidence-based practice [53].

While use of technology in elderly rehabilitation is not widespread within the NHS, a number of localized trials and case studies have shown that technology, in conjunction with new assessment models, can successfully be used to improve health. For example, in 2013, the Community Falls Prevention Programme, led by Anglian Community Enterprise in Essex, reduced waiting times and helped to cut falls-related ambulance call-outs for over 65s in the area by more than half [55].

Home-based and remote rehabilitation in UK

The HSC provides domiciliary care for older adults who live independently in their own homes but require help with personal care and other practical household tasks. On a given survey week (Sep 2017), an estimated 261,000 contact hours of domiciliary care were provided by HSC Trusts with an average of 11.3 hours of care provided per client [56].

Almost 80% of people using homecare services in the UK are over 65 [57]. The range and type of the services vary, e.g. personal care, activities of daily living and essential household tasks. These services are mainly funded by local authorities or the person themselves. However, occasionally these services can be funded by the health care commissioners. Independent homecare agencies, local authorities and personal assistants may be the providers of these services. The homecare of 372,000 people over 65 was funded in part by local authorities from 2013 to 2014 in UK. There has been a decrease in public funding granted for people’s care. As a result, about 270,000 people funded their own homecare and this number is expected to increase and its increment will depend on the person’s wealth and public policy.

In the UK, there are already efforts to expand and decentralize the delivery of rehabilitation. The main advantages of remote rehabilitation are the availability of the service in rural areas (improves accessibility), a reduction in the cost (makes it affordable) and the time involved (reduces waiting and traveling time) [58]. These aspects improve the overall patient experience and involvement. As a result, remote rehabilitation may produce improved outcomes, compliance with treatment and personnel/ patient satisfaction.

The Transforming Rehabilitation Service Programme in the UK is part of the Transforming Community Services Programme by the Department of Health. The latest focuses on setting up what they call a “far-reaching-plan” to resolve long-standing issues faced by the community services p such as the variation in service quality and outcomes; unmeasured activity and achievements; lack of usable data, tariffs and currencies; disparity in quality, productivity and costs; frequently outdated infrastructure and uncertain and confusing access.

As can be observed, the goals of this programme are SENDoc focus. The Transforming Community Services Programme want to achieve mainly improved quality and productivity; build preventive approaches to reduce costs related to lifestyle diseases and their complications [59]. As part of the approach, they will improve services, develop health care provider personnel and align systems to sustain transformation. Specifically, the programme focuses on “High Quality Care for All” and it is focusing on “bringing clarity to quality and measuring quality”.

The Transforming Rehabilitation Services Programme is focused on actions that will be taken to deliver the basics to all community services, such as:

A. To know about the local health needs and to plan services accordingly

B. To create effective care and health partnerships

C. To implement new services and approaches

D. To promote access and availability of services

E. To support care planning and case management

F. To safely manage, handle and share patient information and provide appropriate technology

G. To provide appropriate education and training to form competent health care providers

As part of implementing new services and approaches, creative approaches to service provision will be developed, such as remote rehabilitation. The main objectives are to improve personalization efficiency and effectiveness. An example of an objective that wants to be achieved is to reduce the admissions to acute hospitals. This may include investment in portable technology - laptops, tablets, palms - and web solutions to enable remote access working for clinicians. As a result, health care providers are working on developing a philosophy of rehabilitation and reablement-to provide a clear vision and strategy for rehabilitation services; to provide rehabilitation at home, to monitor a patient’s rehabilitation progress preventing re-admission into hospital, and to involve the local community to support rehabilitation services and reach people that maybe marginalized from society [59].

An example of assistive technology, which will be employed by the Transform Rehabilitation Programme is telecare. The main objectives are to optimize patient wellbeing and health and continuing maintenance. Telehealth will be used to assist people to monitor their own condition. Telephone support and video linkage (telephone) will be employed regularly as part of the rehabilitation programme. It is expected the inclusion of “non-health technologies and services”, such as game products, and leisure centres in the rehabilitation programme of an individual to normalize his/her activity [59].

Challenges of Implementing Remote Rehabilitation

To implement remote rehabilitation, there are several technology related barriers that must be overcome including ethical, usability and acceptability aspects that are experienced by the end-users (e.g. patients, physiotherapists, nurses and GPs). Also, the preservation of privacy and security and the inherent challenges of technology, such as small scale integration, battery life, etc. This section focuses on giving a brief overview of these problems.

Problems related to the Ethics, usability and acceptability of technology

Ethical issues should be considered when implementing new social and health care systems and services. Ethics and equality are written to be the basis of legislation in rehabilitation.

Every technological device or application has its own ethical aspects. It can be said that the development and application of technology is about fundamental human rights, the possibilities of society and the future. For these reasons, members of society should have the right to be aware of and have the opportunity to influence technological development options. Technology itself is not just a product or service, it`s a process and because of that, technological developments need to be assessed in the light of the underlying motives, the goals set for it, the tools and the consequences of its production [60].

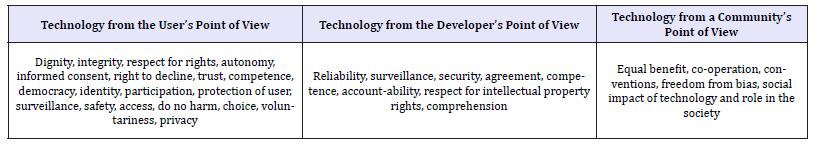

Controversial issues about the ethics of information technology have emerged, for example, regarding data copying, storage and data transfer. Problems related to the control of people and the intrusion of their personal lives have also been problematic. The various problems of information technology ethics (IT ethics) are related, for example, to abuse of technology (e.g. breach of privacy) and to false values (e.g. excessive user guidance in a particular direction). These technology-related ethical issues should not always be looked at through negative matters. It should also be considered how the technology could increase, for example, our self-determination and self-fulfillment. The features shown in Table 1 arise [60] when the relationship between technology and the individual or the community is assessed. These also arise when the relationship between each other’s is evaluated.

Table 1:Features arising when assessing the relationship between technology and the individual or the community.

The relationship between an aging person and technology is affected by the cultural, economic, political and legal factors associated with the life of each person. The impact of these factors should be considered in technology design and technological solutions for elderly people. Today’s oldest generation is not used to using technology, so we can talk about the inequality of technology, though it should support equality and justice. The ethical challenge is how to enable technology for all user groups, such as the elderly [60].

Physical and psychological changes - which come together with older age - make it more difficult to use technology, which is often designed from young generations viewpoint. The most obvious impact is sight decline. Other difficulties can be problems in the range of motion of joints and the decrease of muscle strength. The ability to perform fast and accurate movements also diminishes. The reaction time changes and the ability to multitask, which have an impact on the use of technology. Even the elderly’s ability to learn new things could cause some difficulties. In some degree, IT technology can be unusual to the elderly, and they might have fears concerning it - owed to their ability to use it, viruses and data security or even fears of breaking the equipment - which can cause avoidance using technology. There are differences among age groups of elderly and among country regions. This is also known as “digital gap”, which means an uneven distribution of benefits of IT technology [61].

Technology development should increasingly focus on maintaining and improving older people’s interaction. On the other hand, utilizing technologies can inadvertently even replace valuable social contacts for older people and can reduce social interaction instead of increasing it. Technology should also be seen as an enabler to maintain a social network. It does not eliminate loneliness, but it can be a way of eliminating the feeling of loneliness by creating opportunities for social interaction for the elderlies who, for example, cannot leave their homes due to mobility problems. Each situation should be considered from the perspective of the elderlies’ needs and the opportunities offered by technology [60].

If new technology assisted with activities that elderly people have problems to do or perform, they had more positive attitudes about it [62]. However, we must remember that elderly people still rely heavily on low-technology information, for example, radio, television, news, papers and libraries [63]. Older people want new technology devices to have simple interfaces and demand fewer user skills. They should also be reliable, easy to understand, learn and use without extensive training. Furthermore, elderly people want clear and readable printed instructions. It´s also important to be aware that in remote and rural countries and areas, these new smart technologies are not so easy to implement, because digital or internet services can be unreliable or unavailable [64].

When providing remote services, it is important paying attention to:

A. The health care professional must have the patient’s informed consent for the remote service provided

B. A health care professional must carefully assess whether the service to be provided is appropriate to do via remote services

C. A health care professional should assess individually whether the patient is suitable to be treated via remote services

D. Patient identification must be based on a reliable method provided by the law on strong electronic identification and electronic signatures (617/2009). The method of identification must be verifiable afterwards.

E. Proper patient documentation must be provided for the remote service, and the patient register must be maintained in accordance with the applicable regulations and regulations.

F. Patients should be given the opportunity to receive a personalized reception, if necessary, or the patient should be directed to a treatment place.

Elderly people assess four things in usability that affect their use of new technology. The first thing is availability or accessibility of these new options. For example, how easy it is to buy, lease or rent them, where they live. Secondly, new technology must be affordable for all the elderly people. Thirdly, the elderly must be able to use these new technologies without anxiety, frustration or incompetence. It is important to have a positive user experience and elderly people want these new devices to fit seamlessly on their lives. Finally, the new technology should be enjoyable to use [64].

Typical reported problems that have an impact to usability are:

A. technical problems of connections and devices

B. incompleteness and unsuitability of devices

C. cost of devices compared to profits

D. problems of usage

E. partial solution when several parallel devices and systems are needed

F. fast ageing of solutions [65].

Key issues that promote the use of new technical apparatus among elderly are:

A. proactive knowledge and a collection of experiences from using technology on elderly people

B. the principal thing is the activity/functions and not the technology or the devices employed

C. the correct selection of users and the support of their relatives

D. multi-professional teams, in local elderly services, conduct a central role

E. familiar workers presented the device and it is beneficial to both users and staff and patients/customers

F. the users understand the importance of using the technology, it is easy to use and users experience the benefit of rehabilitation

G. devices generated interesting and usable information and are easy to install and the information is easily available

H. the demands or costs (free of charge) should not be much from the users’ perspective

I. devices should be more or less unnoticeable, and its implementation can be done fast and easy

J. good support should be available from the manufacturer or retailer (installations, updates, orientation, active problem solving). It should be a good value of the technology for the services provided and their development and should not imply very high expenses [65].

Problems related to security and preservation of privacy

The sense of security is also one of the core issues in life management [60]. Maintaining and enhancing your own security are the key areas where elderlies want new technologies to be developed [66]. A feeling of safety is also linked to the use of platforms particularly with other users etc. [67]. Both, technical solutions and security aspects of data storage and transmission, and data legislation, have an impact on planning e-health and remote rehabilitation processes. This is from the point of view of the end-user, clinicians and organizations.

Even though wearable technology has developed rapidly, there are challenges that require more research and development. There are a few technical problems that need to be resolved, but the biggest concern is related to the privacy and security of the sensitive medical information of the user. Further development of algorithms is needed to confirm highly secured communication channels in existing low-power, short-range wireless platforms. Also, low-power consumption and high energy efficiency need further development [68].

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

On January 2012, the EC proposed a comprehensive reform of data protection rules in the EU. On 4th May, 2016, the official texts of the Regulation and the Directive were published in the EU Official Journal [69], in all the official languages. The Regulation entered into force on 24th May, 2016 and is applicable from 25th May, 2018.

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) - Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and Directive (EU) 2016/680 [69]- replaces the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC and was designed to harmonize data privacy laws across Europe. Its main objective is to protect and to empower all EU citizens’ data privacy and to reshape the way organizations across the region approach data privacy. Key articles about the GDPR aim to strengthen and enhance eight Data Protection rules, which can be summarized as follows:

A. Obtain and process the information fairly (consent)

B. Keep it for one or more specified and lawful purposes

C. Use and disclose only in ways compatible with these purposes

D. Keep it safe and secure

E. Keep it accurate and up-to-date

F. Ensure that it is adequate, relevant and not excessive

G. Retain it no longer than is necessary for the purpose(s)

H. Give a copy of his/her personal data to any individual on request.

Under GDPR, any organization must be able to demonstrate compliance with these principles. The Regulation is a starting point towards the common goal of attaining a uniform and high level of protection of citizens’ personal data, which will strengthen confidence, legal certainty and competition with a view to building a new dialogue with citizens, to develop online services, through increasing people’s trust in transactions or line-ups. In the context of SENDoc, the citizens we are focused on are elderlies. Under the new legislation, the elderlies are at the center of the system and will have a higher control over their personal data, the right to data portability, the right to oblivion (recognized so far only at the jurisprudence level), the right to be informed transparently, fairly and dynamically about the treatment of personal data, the right to be informed of violations of own personal data (data breach) [70]. The elder will have the right to be notified by public administrations and businesses of any data protection breach within 72hours, an obligation currently envisaged only in certain areas (health, interchange of data between public administrations and the banking sector).

The new regulation implies strong accountability, a change of pace, a proactive approach, the protection of personal data finally becomes a strategic asset of companies and public administrations that must be evaluated at the time of designing new procedures, products or services. As a result of the provisions of the European Regulation, public administrations have - prior to proceeding with the processing of data - to undertake an impact assessment (“privacy impact assessment”) of the treatment, in particular when new technologies are involved and when, given the nature, object, context and purpose of the treatment, the very same treatment may present a high risk to natural persons’ rights and freedoms. The impact assessment requires a timely and documented risk analysis regarding the individuals’ rights and freedoms concerned.

The European Regulation introduces a number of simplifications of the burden and the fulfilment of the obligations: the abolishment of the obligation of prior notification to the National Authority in case of particularly delicate data processing activity (e.g. genetic, biometric data or data indicating the geographical location of persons or objects via an electronic communication network; data suitable to reveal the state of health and sex life treated for purposes of assisted procreation, the provision of health services, for telematics related to databases or supply of goods, epidemiological surveys, detection of mental illnesses, infectious and diffuse, seropositivity, organ and tissue transplantation and health expenditure monitoring, etc.).

The Regulation introduces for the public authorities the need to appoint a “Data Protection Officer” who must be “involved in all matters relating to the protection of personal data”. The Data Protection Officer must have specific requirements: expertise, experience, independence and autonomy of resources, lack of conflicts of interest, and overseeing organizational privacy profiles through a monitoring work on the correct application of the European Regulation, of privacy and internal law, on the allocation of responsibilities, information, awareness-raising and staff training, information and advice. The Data Protection Officer is a point of reference and contact for citizens who can apply for all matters relating to the processing of their personal data and the exercise of their rights under the European Regulation. In carrying out its tasks, the Data Protection Officer considers his/her duly: “The risks inherent in the processing” by considering the nature, scope, context and purpose of the data.

The text also provides regulations for the strengthening of the powers of the National Guarantee Authorities and the strengthening of administrative sanctions by businesses and public administrations: in the case of violations of the principles and provisions of the Regulation, sanctions may, in special cases, amount to up to €10 million or for firms up to 2%-4% of the total annual worldwide turnover of the previous year, if higher. There are a number of websites which attempt to summarize the Regulation for different audiences including the general public and IT professionals.

Problems inherent to technology

Steins et al. [70] presented a systematic review where they found that accelerometric-based technology is mainly utilized in laboratory settings and that there is a clear need to translate research findings and novel methods into practice. A systematic review of Bergmann & McGregor [71] points out that patients and clinicians prefer wearable sensors to be compact, embedded and simple to operate and maintain. Body-worn sensors must not replace a health care professional or should not affect subjects’ daily behavior. In the future researchers must focus on the implications of users’ preferences when designing wearable sensors.

Applications of wearable sensors can include monitoring, measuring and analyzing health and wellness, safety, home rehabilitation, assessment of treatment efficacy and early detection of problems and disorders. Wearable sensors current possibilities commonly include physiological, biochemical and biomechanical motion sensing. There is a growing amount of activities focused on applications to monitor older adults with chronic conditions at home [4]. Wearable sensors are effective and reliable for preventative processes in variety of medicine areas, such as cardiopulmonary, vascular, endocrine, neurological function and rehabilitation.

Wearable sensors can be integrated into both acute and chronic situations and may provide necessary information for management of health disorders and rehabilitation, for both patients and health care personnel [7]. Tedesco et al. [72] and Majumder et al. [68] have stated and are backup up by several research articles that wearable sensors are most promising technology to do automatic, continuous and long-term evaluation of different aspects of individuals’ physical activity and health state in their everyday living environments.

Majumder et al. [68] concluded that wearable systems should be affordable, easy-to-use, un-obtrusive, and inter-operable among various computing platforms. There should be a minimum number of sensors, but the most important clinical information should not be lost. The ease-of-use of wearable sensors must be further developed. In the future equipment should be more lightweight, with more processing capacities, smaller in size and gain higher usability [73]. The biggest challenge for wearable technology is to integrate several electronic and MEMS (micro-electro-mechanical systems) components and at the same time to ensure the implementation of measurement accuracy, efficient data processing, information security, low-power consumption and, most importantly to ensure the users wearing comfort [68].

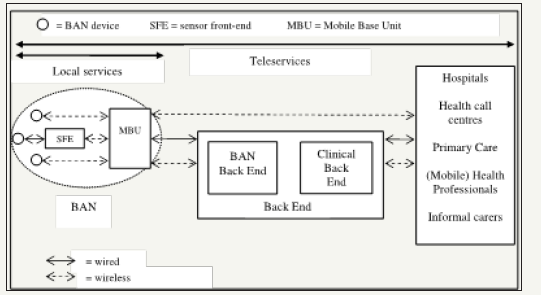

The architectural structure and the solutions of two implemented sensor systems (Personal Health Monitor and MobiHealth) were described by Jones et al. [74] in an article corresponding to the Conference of Digital Society. Its basic structure (Figure 8) is comprised of: 1. BAN devices (sensors, etc.)., 2. A Sensor Front End, 3. MBU: mobile phone, 4. Software of MBU, 5. Processing of MBU, 6. IntraBAN Communications (wired, wireless, etc.), 7. ExtraBAN communications (3G, GMS, WIFI, etc.)., 8. Back- End and 9. Processing on Back-End.

Figure 8:The m-health structure [80, p. 205].

Two problems involved on employing wearable technologies in Medicine are the use of wireless communication for the transmission of data to proximate devices and the software control [75]. This is owed to many devices operating near or within the human body, e.g. mobile and PC. In addition, security must be addressed. Data must be encrypted and under access control to be private and all data collected must be relevant.

Also, it is important to address issues such as poor battery life and the complex design of user experiences, which are also currently observed when using wearable technologies in the fashion field [76]. Other risks that must be managed when employing wearable technologies in medicine is data storage and data processing. Since storage and processing can be currently outsourced to the cloud, the problem is related to privacy and data security from the cloud provider and client’s perspective [77]. From the provider’s view point, the security of the infrastructure must be addressed, client’s data and applications must be protected. From the client’s view point, the access to the data and services in the cloud must be restricted.

Arriba et al. [78] discuss several interoperability issues involved using wearables in real-life environments, such as the available operating systems and sensors, the diversity of devices, problems related to the data models and the different options available to transfer data from wearables to third-party servers. Two approaches - wearable data transfer and warehouse data transfer - are employed to transfer data from wearables. The former is employed when data is taken directly from wearable sensors and the later takes data from the warehouse. Warehouse data transfer has various disadvantages, the most important is its inability to collect real-time data from the device. Data transfer can be completed within several days. In comparison, a wearable data transfer can take place at precise period in time. In addition, some processing is performed over the data at the proprietary warehouse with summarization purposes. Therefore, raw data can only be attained from wearable data transfers. However, it is important to observe that current wrist-worn wearable devices can have problems of memory size, since this is usually very limited, thus frequent data transfers are necessary.

Discussion

It was noted during the research that Finland’s and Sweden’s health care services are currently going through very radical changes. All SENDoc project’s countries are at the moment facing the challenge of aging populations and elderly people’s increasing demand for health care attention. Therefore, the scarcity of available resources to deal with these problems is something that has to be resolved as soon as possible. If the areas are remote, the complexity and cost to reach health care services increases. Remoteness also has an impact on the organization of health care services. Health care services can be private or public. In addition, these countries have their own policies and agendas, which are under ongoing execution and have the common aim of delivering enhanced quality of services.

However, the solutions explored by these SENDoc based countries to manage the scarcity of resources and lower the costs are in some degree similar: decentralization of services and enabling access, e.g. remote/home rehabilitation, e-health, telemedicine, etc. What these solutions have in common is the aim to change elderly patients’ behavior and empower them to be able to manage and follow their own recovery, achieving independent living in their community. At the same time through the use of technology these solutions are working to make health care services accessible and available. All countries are creating or transforming health and social care policies and programmes that will enable the change towards better quality of services.

From the review presented, it was observed that rehabilitation aims to solve the loss of capacity and keep individuals in an optimal state. The goals and the plan of rehabilitation are personal, have to be realistic and also consider the patient’s environment and next of kin. As it can be observed rehabilitation is a broad concept, and SENDoc focuses on elderly rehabilitation.

In all SENDoc’s based countries, remote rehabilitation considers that patients have to become active participant in their own recovery. They attain more control over their condition and empower them. It ultimately seeks a change in behavior to live better and healthier lives. As it can be observed remote rehabilitation has been in execution since about 18 years ago, so it is a very recent concept. As a result, health care staff have yet to be trained. Also, from the partner countries in SENDoc project, some countries are more behind than others moving towards e-Health or connected Health, as is the case of Ireland. Besides, elder patients are starting to be provided with health care services at their homes or like-home places, but ideally the best option would be to prevent a health or capacity decline and avoid the need for provision of home health care as long as possible.

Synchronous and asynchronous remote rehabilitation types are being tested and technology has been a factor that has contributed to make it possible. Home rehabilitation is implemented in people’s homes or in home-like conditions, so they have the potential of freeing resources, such as beds and staff, in acute hospitals, making it more cost-effective in the long term. Also, remote rehabilitation changes the relationship between health experts and patients and making it a more complete approach where cultural and social activities are also considered.

Remote rehabilitation has been possible mainly through advances in technology. Therefore, many of the challenges that remote rehabilitation faces at the moment are related to it. Data storage, copying, transfer and security comprise ethical problems and the new GDPR law has to be considered in every step involved in order to preserve privacy and the rights of the data holder. Strong electronic identification and electronic signatures must be used on patient authentication and to gain access to patient data. In addition, security algorithms have to be advanced in order to achieve a higher level of security on communication channels.

Problems of design have to be avoided in order to create pleasant experiences. Elderly people’s mindset, value, skills and needs have to be considered to avoid this kind of problems. Also, the kind of relationship that the elderly person is going to have with technology must be contemplated. Besides, social interaction must be supported and enabled by technology and not the opposite. In addition, technology must be affordable for all and not to create a feeling of anxiety while being used.