- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Medical & Engineering Sciences

A Conceptual Framework about Interstitial Space between the Bio-Psycho-Social Structures in Medicine General

Jose Luis Turabian*

Specialist in Family and Community Medicine, Spain

*Corresponding author: Jose Luis Turabian, Specialist in Family and Community Medicine, Health Center Santa Maria de Benquerencia Toledo, Spain

Submission: June 04, 2018; Published: June 25, 2018

ISSN: 2576-8816

Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

The conceptual framework presented in this paper argues that basic nature of general medicine are in the “Interstices”: spaces between, rather than within, the familiar boundaries of accepted biological or psychological or social structures, such as “doctor”, “patient”, “family”, “health system”, “symptoms “,” beliefs “,” time”, “place”, etc. “Interstice” here is understood both in the topographical, bio-psycho-social, and metaphoric senses of the term. It refers to a space of the living of people in societies; to the spaces of inclusion and exclusion of people from the production process and relationship; and it refers to the sharp boundaries of the conventional structures. The Interstices are concrete “event spaces”. What exactly happens in the empty interstices of living organisms has not yet been investigated. These interstitial structures have a fundamental bio psychosocial importance and are recognized as the real basis for interdisciplinary research in medicine. The development of general medicine demands new ways of thinking about connections between different elements, and needs also new technologies to work with these connections. These spaces between boundaries are the appropriate places for potentialities to arise, to be creative, to produce novelties, to make bold thoughts. But, these interstices in which the academic discipline of general medicine live and develops are still very narrow. The biomedical and quantitative approaches are like two aircraft carriers that approach and barely leave a narrow gap between one and the other; however, in these gaps, in these clearings, is where general medicine lives, and from where it proposes an affirming, reflective, and transfiguring character of health care.

Keywords: General practitioner; Family medicine; Transitional spaces; Complexity; Theoretical models; Metaphors; Analogies; Virtual worlds; Technologies

Introduction

Interstices: fissures, cracks, openings, spaces, pore; the interstices are everywhere. They exist between things, at the borders; they connect the solid, the tangible, the visible, the measurable, but they themselves are fleeting, vague, invisible, undefined, empty: empty spaces and nothing else [1].

So, this concept referring to general medicine is about nothing? Is this effort to reflect and systematize the concept of interstices in family medicine similar to the architect who wanted to take the space between the boards of a fence and try to build a house from them?

“What really makes a wheel a wheel?” Ask the legendary Lao Tzu, who was an ancient Chinese philosopher and author of the Tao Te Ching: it is the empty spaces between the spokes that essentially constitute the wheel [2]. From this perspective, the interstices in the fence even acquire a certain meaning: the fence also becomes what it is through the empty spaces between the slats.

There is a certain sense of the concept of “interstice” from the modern interdisciplinary sciences. Modern physicists propose what seems to be an equally absurd working hypothesis by asking what would happen if we extracted all the interstices of our planet: there would only be a small ultra compact mass of matter, approximately as big as golf ball, but with the same mass than the whole Earth. If we extracted the interstices of a living being, we would not have very different results; we are composed of 99.9% of empty spaces. If one extracts all the interstices of a person, he would decrease to a few nanometers.

Therefore, the interstices, as well as what happens inside and around them, are clearly of fundamental importance, and are a prerequisite for everything that exists. Without them, there would be no activity, no becoming, no growth, no movement, and no life. We would not exist, nor nature, the world or the universe [1].

Architecture also gives us an image or metaphor of the concept of “interstice”. In a city, the square represents the “space between” or interstice. The square is the meeting place par excellence, where social events and participation, meeting and talk, and communication with others happens. The square can be a function of the general urban layout, or conversely, be the urban structural element which that makes or arranges buildings or structures. The square derives in an urban void which is articulator of traffics of vehicles or interchange of means of transport [3]. Figure 1 presents a first visual approach to the concept of “interstice” or “space between structures” from the “square” image.

figure 1: Interstices/spaces in between.

The development of general medicine demands new ways of thinking about connections between different elements. Thus, in this scenario, through the use of metaphors and images taken from the sciences and arts, a conceptual framework of general medicine is presented, which argues that basic nature of general medicine falls between, rather than within, the familiar or accepted boundaries of biological or psychological or social structures, such as “doctor”, “patient”, “family”, “health system”, “symptoms”, “beliefs”, “time”, “place”, etc., but this “space in-between” is not an “container” but a interstice “relational”.

Discussion

The world is intrinsically interconnected by interstices

The world is intrinsically interconnected. Modern interdisciplinary sciences show us a world that is porous, interconnected. The mathematician, natural scientist and English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead [4], saw the relationships between inorganic and organic biological structures as interdependent. Whitehead was the first to call the empty spaces in the living structures “interstices” and to grant them a fundamental importance when relating them to the theory of the physical field and the interactions of the electromagnetic fields in empty spaces. So, physical fields only become comprehensible through the influences that affect them. According to the resonances and influences of their environment, the flows of virtual energy are subject or not to a process of spontaneous concretization. Life acts as a catalyst; it is a quality of empty space that has the creative function of creating novelty, allowing reality to emerge from potentiality. The real processes of life take place in the “interstices”.

Modern physics no longer addresses the relationship between bodies but what is among them: the behavior of the field in the intermediate spaces is decisive for the organization and understanding of the incidents.

The human being is an interstitial creature; it exists between the macrocosm and the microcosm and forms a kind of interface, a limit of the transmission of biological data between the material and the mind/consciousness. The “mystery” of consciousness lies in the interaction of neuronal and chemical signals that pass between cells and regions of the brain [5,6]. The neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux says: “We are our synapses”, that is to say “we are interstices”, because the synapses are the interstices between the brain cells through which these cells communicate” [7,8].

Organisms or structures can be added to form patches or clusters interspersed with interstices of unoccupied spaces for behavioural or ecological reasons. The territorial space in the clusters could follow, which would lead to apparent regularity. In these circumstances, an analysis of the spatial pattern in a sample area defined by a limit that encloses the clusters could reveal the aggregation but not the regularity. To demonstrate the occurrence of regularity, interstices spacing trends and a organisms or structures density estimate based on a graphical analysis of the nearest neighbour can be used [9]. “Interstice”, regularity and density here are understood both in the topographical sense and in the biological, psychological, social, geographic, and metaphoric senses of the term.

Interstitial container and relational interstitium

A huge conceptual leap that occurs in general medicine is to go from conceiving and describing the interstitial space as a single container in which things inhabit, to conceive and describe it as a space-network of relationships that is established between concrete things. The space-network, however, is not a given space or a priori chosen, but a space that is built from the local relationships that are established between the elements of the space itself. And many times it will be the networks of relationships, which, replacing the initial elements, will work as “points”, as basic pieces or “bricks” of the construction of these spaces [10].

One could think of these relational interstices as in the relations between land and sea, or between mountains and valleys; or, using words from the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke: “Listen to the night’s hollow ring”.

Other metaphorical model to understand the concept of “interstice” is in art. And a frequently used example is that of the painting “Las Meninas” by the Spanish painter Velázquez and his replicas of the also Spanish painter Picasso [11-16]. For Foucault, “Las Meninas” is an exchange of looks between the painter represented in his work and the viewer. Thus there is a constant relationship between the object and the subject in which one takes the place of the other. “Las Meninas” inspired Picasso to make a series of 56 paintings in which he tried to explain and give a reinterpretation of each of the details of Velázquez’s most applauded and studied work.

Velázquez’s canvas, the space between the princess and María Agustina Sarmiento, the maiden kneeling in front of her, is a cubic container external to both girls, while the space between these same figures in Picasso’s painting is a network: the way in which each girl sees the other, and the position in which each of them is placed with respect to the other, gives rise to the network of triangles that as a spatial structure connects them to each other and to the rest of the figures in the room. In fact, the entire scene is composed of multiple local relations that Picasso represents by means of a spatial structure formed by basic geometric figures such as triangles and rectangles [17].

In general medicine, the relationships between actors, situations or structures allow to build environments formed by elements related to each other, and these environments, these networks of relationships, constitute a space-network.

The interstices are concrete “event spaces”

As a metaphor, the interstices represent diffuse, ambiguous, transboundary, transitional, border expansion areas, as well as the unfathomable, unknown, mysterious, seductive and dangerous. The interstices are the creative spaces commonly recognized for new ideas and meanings in the arts, in architecture, literature, music, film, dance, as well as in psychotherapy and counselling of the spiritual life [1].

The interstices serve as a metaphor for change and transition. However, they are more than a metaphor; they not only represent change and transition: they are the true space-time in which change and transition can take place. In these spaces are the events that we think is natural but unpredictable and what seems familiar, but in reality it is strange. These “intermediate” spaces provide the ground for developing individual, community or individual strategies that initiate new identity signs and innovative collaboration sites. The interaction of people, time, place and space forms the dialogue with clinical symptoms and the healing process, and creates new interstices. Box 1 presents an example of interstitial spaces in a clinical case.

Interstices and general medicine

Family Medicine lives in the interstices, and that’s why it’s beautiful. It is the beauty of the threshold: when you enter the threshold of a house it is like an exclamation. General/family medicine is on the threshold of health / disease. The thresholds are fertile. When you can recognize the thresholds you feel a beautiful phenomenon. The threshold is something that guides us, in which I can also stop, a domain that outlines the space that follows and that already existed before [18].

The discourse of health/disease is largely constructed around interstitial spaces: workspaces, the market, transportation, stores, restaurants, ritual spaces, game spaces, sports arenas, houses, corridors, bridges, dining rooms, etc., without the rules of spaces, structures or medical protocols, and so, other things can happen. The health/disease commons type of learning environments work like interstitial spaces, they are neither formal nor informal spaces, and they are institutional but also personal.

The field of family medicine is not the pathologies, nor the bio, psychosocial, nor social. Its field is the “interstices”, the thresholds, between the bio, psycho, social: the experiences of the pathology, the experiences, the beliefs, the relations with the context [19,20]. The bio psychosocial evaluation focuses on the intersection of systems. In this view, the clinical problem that seemed to be located in the cells, or in an organ or organ system, is understood as located in systems outside the physical body, at the threshold of the physical body. The practice of general medicine is a product of the interstitial space where it is located.

Given the cognitive doubt that the general practitioner has, based on a bio-psycho-social case of the consultation, and from that doubt on arrival to a specific theoretical training content that gives security or reduces the uncertainty of decision-making , appear a door, “door of heaven” connecting doors, cosmic doors, thresholds - that take doctor almost instantaneously, magically, to an “interstice” where you access the necessary elements to move from one stage to another with less uncertainty .

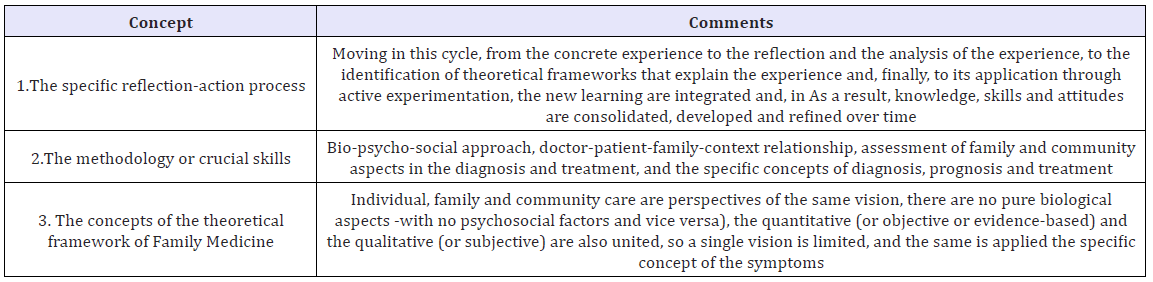

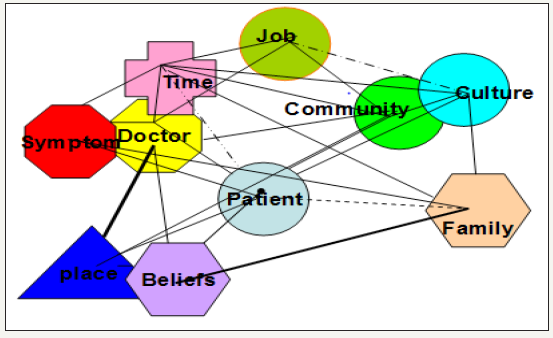

Table 1: The “doors of heaven” that allow to pass through the interstitial spaces in general medicine.

figure 2: A summary scheme of possible interstitial spaces in general medicine.

Am I missing data about a problem or clinical case? Can I perceive the position in the space of the patient, his family and his community in their mutual relationship and in relation to us? To document me more I need less information about the problem and more about its interstices. To know the relevance and significance of a health problem and the intervention on it, it may be necessary to add more information (of the individual, case, event...), but in most cases, the fundamental thing is to advance in the opposite direction: less information and learn more about the interstices (Table 1) (Figure 2). By superimposing the elements one on the other, a geometric hole or hole is created. This site or interstices is surrounded by elements of the network [19-28].

Effectively, the sense of “art” or clinical expertise “is associated with the ability to manage the uncertainty of the query. It is an error the training that tries to eliminate that old concept of “the clinical eye” of the wise (subjective) doctor and emphasize the clinical epidemiology as the only approach (objective) to the medical problems. The important thing is to try to understand the process of the “clinical eye” - the ability to manage uncertainty - and include it in the clinical method. Judgments cannot be true or lie in the abstract (in the generalization of the protocol), but case by case. And that has to be taught and learned by future doctors.

The clinic emerges, is perceived by the clinician, within its theoretical framework that qualifies reality. From that moment, there are a series of clinical strategies to manage the uncertainty of decision making: the internal congruence of the doctor, the congruence with other actors, the internal congruence of clinical semiology, temporal congruence. And each of these strategies has a series of clinical techniques or technologies (understanding “technology” as the science applied to solving specific problems).

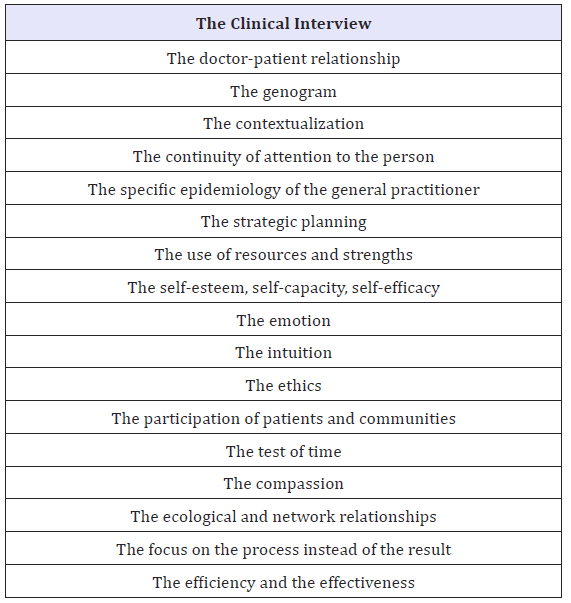

The decision-making process is very complex and depends on the role of each individual: patient, family member of a sick person or doctor. Quality of decision making in modern health care is defined with reference to evidence-based medicine. There are concerns that this approach is insufficient for, and may thus threaten the future of, generalist primary care. We urgently need to extend our account of quality of knowledge use and decision making in order to protect and develop the discipline. Interpretive medicine describes an alternative framework for use in generalist care [29]. Here, general practitioner works by occupying the interstices of daily life, and he uses a series of specific tools specific to the specialty of general medicine to work from these “interstices” between biological, psychological and social structures [30]. Table 2 presents a conceptual approach to systematization of these tools and technologies [19,20,22, 31-39].

Table 2: Specific tools and thecnoligies of general medicine to work in the “interstices” between the biological, psychological and social structures.

Conclusion

“Interstice” here is understood both in the topographical sense and in the social, geographic, and metaphoric senses of the term. It refers to a space of the living of people in societies; the spaces of inclusion and exclusion of people from the production process and relationship; and it refers to the sharp boundaries of the conventional structures. The Interstices are concrete “event spaces”.

What exactly happens in the empty interstices of living organisms has not yet been investigated. These interstitial structures have a fundamental bio psychosocial importance and are recognized as the real basis for interdisciplinary research in medicine. A huge conceptual leap that occurs in general medicine is to conceiving and describing the interstitial space as a spacenetwork of relationships that is established between concrete things, and is not a given space or a priori chosen, but a space that is built from the local relationships that are established between the elements of the space itself. So, many times it will be the networks of relationships, which, replacing the initial elements of patient, doctor, symptom, family, treatment, healing, time, place, etc., will work as basic pieces or “bricks” in the construction of these spaces.

The development of general medicine demands new ways of thinking about connections between different elements, and needs also new technologies to work with these connections. The conceptual framework presented in this paper argues that basic nature of general medicine falls between, rather than within, the familiar boundaries of accepted biological or psychological or social structures, such as “doctor”, “patient”, “family”, “health system”, “symptoms”, “beliefs”, “time”, “place”, etc. These spaces between boundaries are the appropriate places for potentialities to arise, to be creative, to produce novelties, to make bold thoughts [40].

General medicine lives in these interstices. But, these interstices in which the academic discipline develops are still very narrow. The biomedical and quantitative approaches are like two aircraft carriers that approach and barely leave a narrow gap between one and the other; but in these gaps, in these clearings, is where general medicine lives, and from where it proposes a affirming, reflective, and transfiguring character of health care.

BOX 1

The example of a history that tries to show the “interstitial spaces” of several clinical cases

While Dr. Roux was on vacation for a few days, he saw a woman walking slowly through the hotel lobby with her head down. The woman turned to the doctor’s 4-year-old daughter, and with a heavy air said, “Your daughter has conjunctivitis”; an instant and accurate diagnosis. But, the doctor thought that in reality the general appearance of the woman was worse than the conjunctivitis of her daughter; she looked sick. The woman said she knew what she was saying. Her name was Emma Hall. The doctor explained that he was a doctor and he was already treating her with an eye drops...

A few days later, a middle-aged woman from Muskegon, Michigan, accidentally diagnosed a rare disease in another person in the elevator that led to the doctor’s waiting room. If those two strangers had not met in the adjoining chairs of the same waiting room, the man would have remained ill.

The woman, Emma Hall, was from Muskegon, where-would she perhaps be a nurse? -where on buses and commuter trains she had acquired the habit of diagnosing the diseases of other passengers: observing her eyes, the texture of her skin, her tremors fingers Miss Hall quietly entered the elevator at the medical center and quickly assessed the other occupants, patients, companions, workers at the center ... some in warm clothes and others in pajamas or in a doctor’s coat. Since in elevators people do not look people in the eye, she had the opportunity to study them with some care. One had anaemia; other arthritis in the hands and deep wrinkles on the face caused by years of addition to tobacco. The one who was beyond, panting: bad breath; maybe heart failure. And, a man’s eyes was yellow, Miss Hall was still in the elevator, scrutinizing the strange color of the man’s eyes, guessing at them jaundice, perhaps kidney failure.

The yellow-eyed gentleman was accompanied another older man wrapped in his coat-perhaps his brother, she thought, noting the resemblance of the rounded shape of his face. When they went out on the third floor, Miss Hall went out with them, although she should went to the fifth floor, and went to them, and approaching the yellow-eyed gentleman, she said: “Do not we know each other? Maybe you’re from Muskegon, Michigan, where I am from?” The man was not from Muskegon, and he was not very surprised when Miss Hall asked him about his yellow eyes: “I have been suffering from a stomach ache for a couple of months and sometimes with a fever... but I expected it to improve ...” said he.

That same day the yellow-eyed gentleman visited his family doctor, Dr. Roux. He had symptoms related to biliary obstruction (jaundice, abdominal pain and cholangitis). Subsequent studies showed absence of lithiasis in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis) or a tumor mass Paraclinical reports of the liver profile indicated that the patient was suffering from a pattern of jaundice obstructive, due to direct hyperbilirubinemia Finally, Lemmel’s syndrome was diagnosed, a rare cause of jaundice, and then a papillotomy and biliary stent placement were performed.

A few days later, Dr. Roux received an emergency call from a patient who had developed hypoglycaemia; it was a patient named Emma Hall, with diabetes and other diseases, who was now in psychiatric treatment.

References

- Reinecke M (2015) Interstices/spaces in between. The hidden arena of actuality. X Scenografic-Colloquium DASA in Dortmund 2012.

- Lao Tzu, Ching TT. A comparative study, Chapter 11.

- García ZE (1996) The city in grid or hispanic american city. Institute of Iberoamerican Studies and Portugal, Salamanca, Spain.

- Whitehead AN (1978) Process and reality. An essay in cosmology. Gifford lectures delivered in the University of Edinburgh during the session 1927-28. In: David RG, Donald W (Eds.), Sherburne. A Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc, The Free Press, New York, USA.

- Damasio AR (1994) Descartes’ error: emotion, reason, and the human brain. Grosset/Putnam, New York, USA.

- Damasio AR (1999) The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Harcourt Brace and Co., New York, USA.

- LeDoux JE (1993) Emotional memory: In search of systems and synapses. Ann NY Acad Sci 702: 149-157.

- LeDoux JE (2002) Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. Viking Penguin, New York, USA

- Campbell DJ (1995) Detecting regular spacing in patchy environments and estimating its density using nearest-neighbour graphical analysis. Oecologia 102(2): 133-137.

- Rilke RM. The rainer maria rilke archive. Third Duino Elegy.

- Martín CF (2009) Velázquez y el retrato del espacio. Revista Suma, Febrero, pp. 73-78.

- Ayala R (2017) How Foucault interprets Las Meninas, the most studied and misunderstood work. CC Arte; Sábado, 11 de marzo 7: 57.

- Meeres H (2016) Las-meninas-velazquez-and-picasso. Barcelona (Draft).

- https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Las_Meninas

- Coughlin AC (2017) Tracing the interstice: Godard, deleuze, and the future of cinema. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository, p. 4741.

- Picasso, Diego Velazquez. Las meninas. History of Art 17th CenturyBaroque.

- Corrales RC (2004) Salvador Dalí y la cuestión de las dimensiones. Sección En un cuadrado. Suma-Revista Sobre La Enseñanza Y Aprendizaje De Las Matematicas 47: 99-108.

- Turabian Jl (2018) The condition of in-betweenness is a structural characteristic of chronic disease. Analogies for understanding. Sci Fed Journal of Chronic Diseases.

- Turabian JL (2018) The concept of co-treatment or ecological treatment in general medicine. Int J Glob Health 1: 1.

- Turabian JL (2018) Community medicine from the point of view of the general practitioner: Never plump your foot straight into your shoe in the morning. International Journal of Advanced Community Medicine 1(1): 44-50.

- Turabian JL (2018) The general physician who only attends “interesting cases”. Am J Family Med 1(1): 1002.

- Turabian JL (2017) How do family doctors cure, resolves, and treat? J Gen Pract (Los Angel) 5: e118.

- Turabian JL (2017) Fables of family medicine. A collection of fables that teach the principles of family medicine. Editorial Académica Española, Germany.

- Turabian JL (2017) Fables of family medicine: A collection of clinical fables that teach the principles of family medicine. SM J Fam Med 1(1): 1006.

- Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B (2016) The family doctors: Images and metaphors of the family doctor to learn family medicine. Nova Publishers, New York, USA.

- Turabian JL, Perez Franco B (2012) The symptoms in family medicine are not symptoms of disease, they are symptoms of life. Aten Primaria 44(4): 232-236.

- Turabian JL (2017) For decision-making in family medicine context is the final arbiter. J Gen Pract (Los Angel) 5: e117.

- Turabian JL, Franco BP (2017) Responses to clinical questions: specialistbased medicine vs. reasonable clinic in family medicine. Integr J Glob Health 1(1): 1-5.

- Reeve J (2010) Protecting generalism: moving on from evidence-based medicine? Br J Gen Pract Jul 60(576): 521-523.

- Savin-Baden M, Falconer L (2016) Learning at the interstices; locating practical philosophies for understanding physical/virtual interspaces. Interactive Learning Environments 24(5): 991-1003.

- Turabian JL (2017) Family genogram in general medicine: A soft technology that can be strong. Res Med Eng Sci 3(1): 1-6.

- Turabián JL, Pérez FB (2001) The future of family medicine. Aten Primaria 28: 657-661.

- Turabian JL (2018) Contextual treatment: a conceptualization and systematization from general medicine. Int J Fam Commun Med 2(3): 137-144.

- Turabian JL (2018) Prognosis-based medicine-the importance of psychosocial factors: Conceptualization from a case of acute pericarditis. Trends Gen Pract 1(1): 1-2.

- Turabian FJL, Perez FB (2003) Notes on «resolutivity» and «cure» in family medicine. Aten Primaria 32(5): 296-269.

- Turabián FJL, Pérez FB (2003) Crucial skills of the family doctor and its implications in management and training: diagnosis, treatment, cure and resolution. Notebooks of Management 9(2): 70-87.

- Turabian JL, Perez FB (2005) A way to make clinical pragmatism operative: Sistematization of the actuation of competent physicians. Med Clin 124(12): 476.

- Kapmeyer A, Meyer C, Kochen MM, Himmel W (2006) Doctors’ strategies in prescribing drugs: the case of mood-modifying medicines. Fam Pract 23: 73-79.

- Landstrom B, Rudebeck CE, Mattsson B (2006) Working behaviour of competent general practitioners: Personal styles and deliberate strategies. Scand J Prim Health Care 24(2): 122-128.

- Turabian JL (2017) Creativity in family medicine. Res Med Eng Sci 1(2): 1-3.

© 2018 Jose Luis Turabian. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)