- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Medical & Engineering Sciences

Unspoken Words: Overcoming Head and Neck Silencing Tumors

Noura Y AlSalloum1, Balaji P Duraisamy2 and Sami A AlShammary2*

1Department of Family Medicine and Employee Health, King Fahad Medical City, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Palliative Care, King Fahad Medical City, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author: Sami A AlShammary, Department of Palliative Care, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Submission: December 18, 2017; Published: February 26, 2018

ISSN: 2576-8816Volume3 Issue5

Introduction

Imagine a boat in the middle of the sea, a small boat with only you on it. Think of why you were on this boat, what reasons got you there, and where would your coming destination be. Try to think of things you might be afraid of during your journey, what might your concerns be? Now imagine being in similar isolation in real life; incapability to communicate it leaves one on that lonely boat. Thompson and Mc Keever describe being unable to communicate so accurately when they brought the inability to communicate as being "trapped in the present" [1]. This case reflection shall follow Rolfe et al.'s model of reflective practice "What? So What ? Now What? " [2].

Case History: What?

During my rotation in Palliative Care, I came across an encounter that had taught me essential lessons in communication and compassion. We present a case of a patient who has communication difficulties; the patient is given the pseudonym of "Ahmed". Ahmed is a 50-year-old Saudi male, with skin squamous cell carcinoma on the left side of his face. His lesion expanded to invade his left eye, his nose, his lips, and the left side of his palate. His tumor had cost him the loss of vision in one eye, and it had taken away his voice. He is breathing through a tracheostomy and feeding via a gastrostomy tube. He also has hearing loss that left him with multiple communication barriers.

The first time I had an encounter with a patient, I was not able to establish rapport as he seemed agitated or just not in the mood for interaction, I had thought to give him his space and try communicating with him later, he got up of the bed and went to the bathroom; that's when I understood that I had misread his behavior. I visited him later in the afternoon of that day, and he communicated through a notebook, he required one to write for him in order for him to read and then reply. patient had a list of his basic needs, because of his language difference, his basic needs were written in Arabic and had an English translated sentence beside the Arabic phrase so that he can communicate with non- Arabic speaking nurses. He asked me to translate more phrases for him, and then he asked if I could make a photocopy of his list; his paper had gotten withered and soiled with water, which stained the ink (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The list of patient's needs stained and crumbled.

So What? The Implication of Communication Difficulties on the Individual

The impact of communication difficulty may range from personal feelings of anxiety, panic, and frustration, to having a higher risk for preventable adverse events; including unnecessary restraint use [3]. Barriers to communication can be because of language disorders, speech disorders, cognitive disorders, hearing loss or because of language differences. Language disorders, or aphasias, occur when there is a problem in language analysis or expression due to a brain injury. These would be reflected in both spoken and written language forms; a patient with Broca's aphasia will have the difficulty of expression in both spoken and written language, while a patient with Wernicke's aphasia will express fluent jargon without making much sense in, also, both spoken and written languages.

The patient had an intact language center proven by his ability to write fluently and eloquently (Figure 2). Speech disorders reflect a problem or pathology with word output rather than the brain, for example, difficulties in pronunciation of certain letters; as in cleft palate, stuttering, or as in the case this paper is concerned about,speech difficulties can happen because of lesions that involve the mouth as what may develop from head and neck cancers (HNC). Cognitive communication disorders mean that both language and speech are intact, but there could be a problem with memory, orientation, attention, or any other reason that could disturb one's cognitive state. Hearing loss is a barrier to communication, which without proper management can insulate one from the surrounding sounds, regardless of having anintact language center and speech abilities, causing an obstacle to interaction.

Figure 2: the patient ‘s written list of some issues that were bothering him.

Language differences remain a communication barrier in Saudi Arabia due to a large number of expatriate healthcare workers. Even though recruited expatriates are proficient in English, a lot of Saudis do not understand English that well. Non-Arabic speaking staff might even find difficulty in establishing good rapport to begin with because of language differences [4]. Concluding from the preceding description of barriers, the patient had a speech barrier, hearing loss, and a language difference barrier.

So What? Implication of Communication Difficulties with Saudi Patients

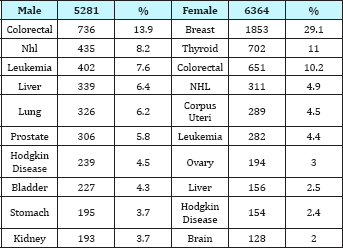

Table 1: Most common cancers among Saudis by gender, Cancer Incident Report, 2013.

HNC is prevalent worldwide to rank the 9th most common cancer globally (Ferlay et al., 2013). Saudi Arabia is divided into 13 regions, with a population comprising 20,180,080 Saudis and 9,723,214 non-Saudi's. The total number of cancer new cases from the start of January to end of December of 2013 was 15,653 (11,645 Saudis, 3,356 non-Saudis). The most common cancer among Saudis (Table 1) was breast cancer in females (29.1%) and colorectal cancer in males (13.9%) [5]. HNC, more so oral cancer, was found to be highest in Jazan region, a region in the southwest; and this higher incidence can be attributed to area specific habits of chewing smokeless tobacco and Khat [6]. There was a lack of pooled prevalence rates of HNC in Saudi Arabia, but the registry can give an impression of the prevalences of tumors that are involved in the HNC regions.

The majority of these types cancer patients will be referred to palliative care service.Palliative care is a relatively new medical speciality in Saudi Arabia, but it has shown tremendous growth in the last two decades [7].

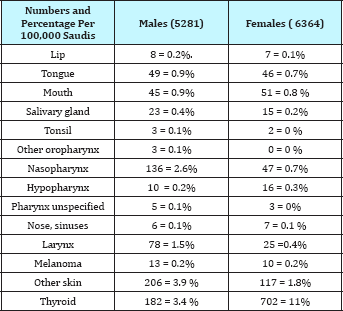

Palliative care will cover all life aspect including physical, spiritual and emotional symptoms management. Multidisciplinary palliative care team need to invent highly professional communication skills for those expressing difficulties in verbal communication. Communication with those who have cancer is demanding of a patient-centred approach. It has to help patients handle bad news they receive, handle the intense emotions that arise at the end of life, understand complex information, face uncertainty but hold on to hope, build a long trusting relationship with their providers, and help them make autonomous decisions about their own health [8]. Patient-centered communication would be even more challenging if a patient suffered a barrier such as speech difficulty. There were no data measuring the prevalence of speech difficulties in HNC patients nationally, but looking at data from the Saudi Cancer Incident Report in 2013, the following cancers (Table 2) may, but not necessarily, involve the oral cavity or impair speech with cancer progression and invasion. One can speculate a speech difficulty need to arise at anytime [5].

Table 2: (per 100,000) of New Cases by Primary Site and Sex among Saudis. Cancer Incident Report, 2013.’

Studies on communication with patients at theend of life who have a speech-impairing associated with cancer were also lacking. Internationally, a cross-sectional study conducted in Amsterdam found speech self-reported problems to be present in 55% (26/ 47) in patients with an HNC post chemo radiation by using the Speech Handicap Index (SHI) [9]. Another study from Amsterdam was a cohort that followed 22 patients post therapy for speech or voice pathologies to arise after 10 years from receiving their treatment; noting they were disease-free when included in the cohort. Assessment was done by validated tools, the SHI and the Voice Handicap Index, and two speech language pathologists; speech and voice problems had developed (77% and 68% respectively) by the use of the self reported tools, and by expert speech language pathologists 64% had an abnormal evaluation [10]. In the United Kingdom, one-third of a cohort of 63 patients with oral cavity or oral pharyngeal cancers self-reported speech difficulties on the SHI and had worse speech outcomes than those with tonsillar cancer [11]. In a multi-center study across Canada, USA, and Finland, SHI was administered on 117 anterior-tongue cancer patients with partial glossecto my and found significant speech difficulties at one and six months post-operation, but backed to a non significant level at one year [12].

Now What?

Figure 3: Vinyl covered paper of patient needs.

Overcoming communication barriers can be achieved, and at least alleviated, by the professional assistance from a Speech- Language Pathologist; it is worth noting that speech therapy requires concurrent psychological assessment, as the burden of disease would have patients in need to talk about their personal issues. More so, I had taken a photo and typed his new sentences, printed his list in an A3 paper and covered it in vinyl material. The next day I have provided this paper to him with a whiteboard marker. It would be more durable for him, it would be protected from fluids and the writing is in a big font. Additionally, scrabbles from the whiteboard marker can be erased and the paper would look neat (Figure 3). Hopefully, he will benefit from his basic need list throughout his stay. Furthermore, he should be trained for other means of communication as a future precaution in case the tumor eventually invaded his other eye. Encouragement of the patients, their families, and healthcare providers is necessary. Professional limits must be respected in aims of avoidance to succumb into falling into the over whelm of "helper syndrome" [13].

The use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication is to be considered and individualized in respect to patient requirements. One of the interesting mnemonics to help in our approach tocommunication is the FRAME mnemonic; by familiarizing oneself on how the patient communicates before interviewing them, reducing the rate of interchanged messages, assisting with communication, mixing communication methods and not relying on one way, and by engaging the patient and respecting their ability and autonomy and not only relying on their families or watchers [14].

Take home messages from this encounter was the necessity of patience with cancer patients, especially in ones suffering from a speech difficulty; they are the ones requiring a gentle listening ear to what they cannot speak. Empathy is keyand a professional's input is prudent, so is family involvement and counseling to encourage them to engage with their loved ones and respect their autonomy. Each life deserves a proper assessment, an autonomous humane end of life care, a decent quality of communication and a non-isolated farewell. Coming up with a vinyl-covered A3 paper was a quick, non-costly way of trying to improve his Communication during my rotation. The list in the paper can be remodeled to a standardized one that covers the basic needs of Hospitalized Arab patients who suffer a speech difficulty along with a language difference barrier; it is non-costly, reusable to other admitted patients and can be disinfected. Recommendations for future studies in the Arab world is to test this document and note the most frequently used phrases so that a standardized form can be scientifically generated.

References

- Thompson J, McKeever M (2014) Improving support for patients with aphasia. Nursing Times 110(25): 18-20.

- Rolfe G, Freshwater D, Jasper M (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user's guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan,USA.

- Radtke JV, Baumann BM, Garrett KL, Happ MB (2011) Listening to the Voiceless Patient: Case Reports in Assisted Communication in the Intensive Care Unit. J Palliat Med 14(6): 791-795.

- Almutairi KM (2015) Culture and language differences as a barrier to provision of quality care by the health workforce in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 36(4): 425-431.

- Cancer Incidence Report Saudi Arabia (2013) Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Saudi Health Council Saudi Cancer Registry. pp. 1-88.

- Alhazzazi TY, Alghamdi FT (2016) Head and Neck Cancer in Saudi Arabia: a Systematic Review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 17(8): 4043-4048.

- Alshammary SA, Abdullah A, Duraisamy BP, Anbar M (2014) Palliative care in Saudi Arabia: Two decades of progress and going strong. J Health Spec 2(2): 59-60.

- Epstein RM, Street RL (2007) Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Bethesda, USA.

- Rinkel RN, Verdonck-de LIM, Doornaert P, Buter J, Bree DR, et al. (2016) Prevalence of swallowing and speech problems in daily life after chemo radiation for head and neck cancer based on cut-off scores of the patient-reported outcome measures SWAL-QOL and SHI. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273(7): 1849-1855.

- Kraaijenga SA, Oskam IM, Son VRJ, Hamming-Vrieze O, Hilgers FJ, et al. (2016) Assessment of voice, speech, and related quality of life in advanced head and neck cancer patients 10-years+ after chemo radiotherapy. Oral Oncol 55: 24-30.

- Dwivedi RC, Rose SS, Chisholm EJ, Bisase B, Amen F, et al. (2012) Evaluation of speech outcomes using English version of the Speech Handicap Index in a cohort of head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol 48(6): 547-553.

- Dzioba A, Aalto D, Papadopoulos-Nydam G, Seikaly H, Rieger J, et al. (2017) Head and Neck Research Network. Functional and quality of life outcomes after partial glossectomy: a multi-institutional longitudinal study of the head and neck research network. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 46(1): 56.

- Ullrich P, Wollbruck D, Danker H, Kuhnt S, Brahler E, et al. (2010) Psychosocial Demands of Speech Therapy with Head-and-Neck Cancer Patients: Clinical Experiences, Communicative Skills and Need for Training of Speech Therapists in Oncology. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(1): 22.

- Michael BI, Baylor CR, Megan MA, Mcnalley TE, Yorkston KM, et al. (2012) Training healthcare providers in patient-provider communication: What speech-language pathology and medical education can learn from one another. APHASIOLOGY. 26(5): 673-688.

© 2018 Noura Y AlSalloum, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)