- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Medical & Engineering Sciences

The Effects of Retrospective Household Income on Neurocognitive Disorders: Results from Project Frontier Data

Hosik Min1, Roma S Hanks1*, Benjamin D Hill1, Diego F Alvarez1, Leigh Johnson2 and Sid E O'Bryant2

1University of South Alabama, USA

2University of North Texas Health Sciences Center, USA

*Corresponding author: Roma S Hanks, University of South Alabama, AL, USA

Submission: January 22, 2018; Published: February 22, 2018

ISSN: 2576-8816Volume3 Issue5

Retrospective Household Income as an Index of SES

The relationship between health status and socioeconomic status (SES) has been well known. Having a disease or illness is not only a medical or biological process but also a social outcome [1-4]. SES can be measured by several variables such as education, income, and occupation. For instance, an individual is more likely to use brain function, which inhibits to develop neurocognitive disorder, when a person has more education and/or higher occupational status [5-8]. Several studies reported a negative correlation between SES and cognitive disorders, whereby the higher the SES, the lower the chance of being diagnosed with a cognitive disorder [7,9,10]. This paper utilized household income as an SES index. Household or individual income is not thoroughly investigated in terms of their relationship with neurocognitive disorders [10,11]. Income may not be directly connected to brain use, yet it has significant relationship with lifestyle, health insurance and health cost coverage, all of which have a documented impact on health status [10,12].

Frontier Study

We utilized the data from the FRONTIER study (Facing Rural Obstacles to healthcare Now through Intervention, Education, and Research) to investigate this relationship. The FRONTIER study is an epidemiological study to explore the natural course of chronic disease development and its impact on longitudinal cognitive, physical, social, and interpersonal functioning in a multi-ethnic adult sample from rural communities of West Texas [13]. Anyone in the area who are 40 or above participated in this study and they were followed over time to test for changes in physical, mental, and cognitive health and the factors that may influence those changes [14]. This study is a community-based participatory research program in rural west Texas and 41% of the sample is Hispanic.

Effect of Income Trajectories on Neurocognitive Disorders

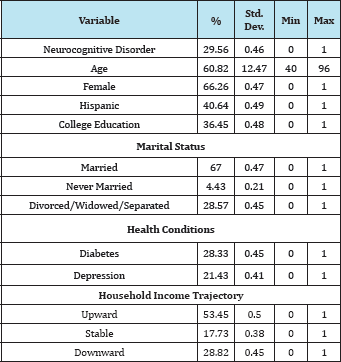

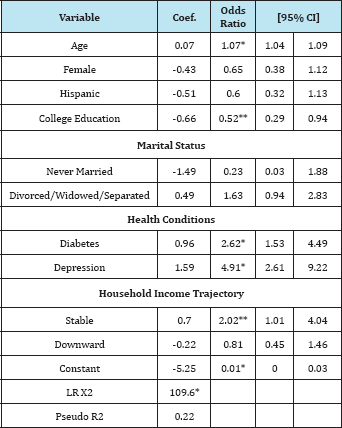

A total of 406 cases those had retrospective household income information were selected for this study: 30% of samples had a neurocognitive disorder, mean age was 61 years old (SD 12.47, range 40-96), two thirds were females, 41% were Hispanics, and 37% had college education. About two thirds were married, 4% were never married, and 29% were divorced/widowed/separated. Approximately 28% had diabetes, and 21% had depression. Income was measured retrospectively, from age 20s to 60s: Almost half of cases had an upward trend for household income over time, 18% of cases had stable income, and 29% of cases had a downward trend for income (see Table 1). Logistic regression was employed to classify either the presence or absence of a neurocognitive disorder. Results found the overall model fitted well and most variables were significant in expected ways. The household income trajectory, the main focus of this study, supported the hypothesis partially. Individuals with stable household income were 102% more likely to have a neurocognitive disorder than individuals with an upward trend for household income trend, suggesting that an upward trend for income was protective. A downward income trend, however, did not significantly lead to greater risk of developing a neurocognitive disorder (see Table 2).

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics (N = 406).

Table 2: The Results of Logistic Regression Model (n = 406).

Need for Further Study

This study estimates the effect of the income trajectories on neurocognitive disorders for a rural sample with a large number of Hispanics. Given the aging of our population and lengthening life expectancy [15, 16] the prevalence of neurocognitive disorders such as dementia continues to increase, particularly for Hispanics [17-19] and constitutes an important public health issue. The study categorized the income trajectory in three ways and found that upward income trajectory indeed played a protective role, yet the downward trend variable did not at first show any significant associations. When we separated the respondents of the downward variable into retired and non-retired ones, we found that respondents with downward income trends and non-retired individuals were more likely to have a neurocognitive disorder. Despite this supportive evidence, it is necessary to note that the sample was small, only 48 cases. The results indicate that income decline for retirees does not correlate with a neurocognitive disorder, as most individuals experience household income decline after retirement [20,21]. Further study is required to determine this association. Finally, our results should be interpreted cautiously and replication is required due to non-representative sampling and small sample size as described above.

References

- House JS (2002) Understanding social factors and inequalities in health: 20th century progress and 21st century prospects. J Heal Soc Beh 43(2): 125-142.

- Link BG (2008) Epidemiological sociology and the social shaping of population health. J Heal Soc Beh 49(4): 367-384.

- Percy JN, Keppel KG (2002) A summary of health disparity. Pub Heal Rep 117(3): 273-280.

- Phelan J, Link BG, Tehranifar P (2010) Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Heal Soc Beh 51(s): 28-40.

- Martin Prince (2009) Alzheimer's Disease International.World Alzheimer report 2014: dementia and risk reduction - An analysis of protective and modifiable factors.

- Seifan A, Schelke M, Obeng-Aduasare Y, Isaacson R (2015) Early life epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease - a critical review. Neuroepid 45(4): 237-254.

- Sosa-Ortiz AL, Acosta-Castillo I, Prince MJ (2012) Epidemiology of dementias and Alzheimer's disease. Arch Med Res 43(8): 600-608.

- Usman S, Chaudhary HR, Asif A, Yahya MI (2010) Severity and risk factors of depression in Alzheimer's disease. J Coll Physi Surg 20(5): 327-330.

- Karp A, Kåreholt I, Qiu C, Bellander T (2004) Relation of education and occupation-based socioeconomic status to incident Alzheimer's disease. Am J Epid 159(2): 175-183.

- Smith JP (2017) Unraveling the SES-Health Connection, USA.

- Rözer JJ, Volker B (2016) Does income inequality have lasting effects on health and trust? Soc Sci Med 149(C): 37-45.

- Hutchison ED (2010) A Life course perspective. In: Hutchinson [Ed.], In: (4th edn) Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, USA, pp. 1-38.

- O'Bryant SE, Zhang Y, Owen D, Cherry B, Ramirez V, et al. (2009) The Cochran county aging study: methodology and descriptive statistics. Tex Pub Heal J 61(1): 5-7.

- Project FRONTIER, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, USA.

- Alzhemer's Association (2017) Alzheimer's disease facts and figures.

- Doblhammer G, Fink A, Fritze T, Gunster C (2013) The demography and epidemiology of dementia. Geriatr Ment Heal Care 1(2): 29-33.

- Hazzouri AZ, Haan MN, Neuhaus JM, Pletcher M, Peralta CA, et al. (2013) Cardiovascular risk score, cognitive decline, and dementia in older Mexican Americans: The role of sex and education. J Am Hear Assoc 2(2): e004978.

- Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, et al. (2003) Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(2): 169-177.

- Mejia-Arango S, Gutierrez LM (2011) Prevalence and incidence rates of dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia in the Mexican population: data from the Mexican health and aging study. J Aging Heal 23(7): 1050-1074.

- Charness N, Czaja SJ (2011) Raising the minimal retirement age: psychological issues. Pub Pol Aging Rep 2(2): 31-34.

- Hooyman NR, Kawamoto KY, Asuman Kiyak H (2015) Aging Matters: an Introduction to Social Gerontology. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey:Pearson, USA.

© 2018 Hosik Min, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)