- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Narrative and Meaning of Life: How Mental Health Nurses can Respond

Jan Sitvast*

Senior Lecturer, University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands

*Corresponding author: Jan Sitvast, Senior Lecturer at University of Applied Sciences, Hogeschool Heidelberglaan 7, 3584CS Utrecht, The Netherlands

Submission: February 28, 2018;Published: March 28, 2018

ISSN 2639-0612Volume1 Issue1

Summary

What is already known about the subject?

A. There are quite a number of studies on narrative and recovery, but few which combine them with emotional intelligence and skills nurses must have to respond to service users’ narrative

B. How a credible internal and external representation of reality is a necessary condition for humans to adapt to the contingencies of life is known from evolutionary biology, but has not yet been related to nurses’ responses to service users’ narrative

What does this paper add to existing knowledge?

A. An integration of concepts and theory from different domains of knowledge and relating them to the praxis of recovery and recovery oriented nursing

B. The central role of meaning giving processes as part of the internal representation and self-image of service users

C. Insight in how concrete and palpable/visual representations facilitate giving and receiving feedback from (relevant) others and can be considered instrumental in creating a working alliance between the care professional and the client

What are the implications for practice?

Awareness is necessary that reflection on the meaning of one’s life, the choices one has to make must be represented in order that others (e.g. nurses) can share these representations or narratives with someone and respond to them. When these representations take on a more palpable and visually form this can be considered helpful.

Abstract

The article is about how people use narratives to make meaning from their experiences when tackling the impact on their lives and the consequences of mental health problems. It also goes into recovery and how recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life. The article describes how ‘man’ is involved in a constant interaction with his environment, adapting himself as well as possible to that environment in order to upkeep his own biological system. Using his cognitive capacities a person can make an internal representation of reality that also encompasses how one relates to reality. It is argued that there is a need for a story about oneself and one’s relationship with the world that represents one’s intentions, goals and values in a credible way. The article describes how nurses can respond to service users’ narrative. We will argue that visualization of someone’s narrative contributes to a shared narrative and will stimulate further reflection on the things that are important in life.

Relevance for Clinical Practice

The notions of hope, enaction, adaptation, internal and external representation may assist professionals in supporting and facilitating recovery in mental health care. Beside narrative means that may be applied in clinical practice two unconventional tools have been described to facilitate reflection on the meaning of one’s life. These are: using photography and the Yucel method.

Introduction

In eMenthe, an European funded international educational project between universities of applied sciences to improve mental health nursing, one of the conclusions was that there is a need for a conceptual framework that encompasses key concepts related to emotional intelligence to support mental health nurses in recovery oriented care. In order to be recovery oriented mental health nurses (and their educators) should focus on identity, hope, meaninggiving and empowerment [1]. Mental health nurses must develop emotional intelligence in order to support patients in recovery and become more hopeful. Narratives play a central role because it is through narrative that service users frame a more hopeful future, not determined by disease symptoms.

Recovery can be defined as “a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by the illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness” [2]. This definition focuses on how the person gives meaning to experiences in daily life and the values, goals, skills and roles that go with them.

The focus is on self-reliance and in its wake self-management, directing one’s own recovery and being active participants in the process of shared decision making. When it comes to selfreliance and self-management, it is important to distinguish different domains of recovery: functional recovery, which stands for mastering again psychological, social and physical functions; clinical recovery, that is ultimately the remission of disease symptoms; social recovery, representing the taking up of old and new roles again and personal recovery concerning the identity and self-image [3].

When we turn to clinical and functional recovery then the clinical relevance of ‘meaning in life’ is evident. A growing number of studies demonstrated lower levels of psychopathology and better response to therapy [4], as well as lower levels of fear, anxiety and depression [5,6], less suicidal ideation [7], and a positive impact on posttraumatic stress and less experiential avoidance when a person is able to give meaning to life [8]. By drawing on their sense of life’s meaning, Triplett et al [9] suggest, people cope better with traumatic life events. The relevance of the process of meaningmaking for social recovery has been demonstrated in many studies, for instance on psychiatric stigma [10,11]. These findings illustrate the broader relevance of the process of meaning-giving in recovery, but in this article we will focus on personal recovery, as this domain is considered by authors and service users alike as most important and also the culmination of recovery in the other domains [12]. We will reflect on how people use narratives to make meaning from their experiences when tackling the impact on their lives and the consequences of mental health problems [13-17].

Design and Method

The argument in this theoretical paper is developed from the focus on identity, hope, meaning-giving and empowerment that Stickley et al. [1] recognized as important for advanced mental health nursing practice. We will argue that the process of meaning giving has a biological evolutionary basis and is linked up with cognitive actions to narrativize sensations and impressions of the inner and outer world. The notions that we will develop may assist professionals in supporting and facilitating recovery in mental health care.

Narrative

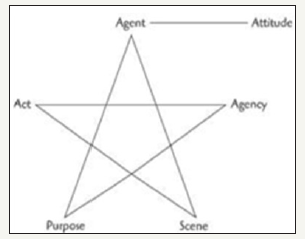

Narrative holds a central place in (facilitating) recovery [18,19]. Although there is more than one theory about how people construct narrative [20-22], we will focus here on the classic approach of Burke [23], because goal formulation (an important aspect of hope) plays a central role in it. Burke uses the word ‘story’, where it may be considered interchangeable with ‘narrative’. According to Burke the story structure consists of five elements (the pentad) (Figure 1). In a story we always have an agent (actorship), an action, a goal, a setting, and an instrument. In a story something happens and is made to happen by the main character(s). That’s what we call the action. The main character (agent) acts in order to realize his goal or at least there is some intention in his acts. There must be a drive behind the story. Usually there is some kind of trouble that triggers the story to take its course [51]. This can be anything from troubling difficulties, death, struggle, whims of fate, shame and guilt. In the case of people experiencing mental health distress, an important drive can be inferred from the struggle to survive ‘mental illness’ and treatment, including hospitalization. This struggle involves suffering, be it a suffering from decreased self-esteem, or be it from the stigmatizing influence from others. Overcoming the pain from stigma and decreased self-esteem by developing a narrative that restores credibility to the intentions and goals of the actor will contribute to hope (Figure 1).

Figure 1: : Burke’s Pentad.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 unported license.

Hope is operationalized as consisting of three dimensions: goal formulation, path-finding and agency [24]. People have higher hope levels as they can have personal goals they want to realize in life. There must be something to strive for that makes life worth living. Having a goal is however not enough in itself. It must be a realistic goal that can be attained, otherwise it gives false hope that in the end will disillusion a person. Besides, the person must have some idea of how their goal can be realized. This is path-finding and consists of having knowledge of the different options that lead to a goal and then being able to pick the option that is best fitted to the job. What option is best fitted to the job depends on an understanding of one’s motivation, personal qualities and skills. One can have an attainable goal in life, know how to get there, but go amiss when it comes to a realistic evaluation of one’s skills that are necessary to walk the path that leads to realization of one’s goal. In other words, one needs a credible coherent story in which the elements of Burke’s pentad are tuned to each other in order to be able to act accordingly and ‘live the story’. How does this relate to the exigencies of daily life and how a person is connected with others and the world around him?

Awareness, Identity and Adaptation

Evolutionary biologists claim that ‘man’ is a complex adaptive system involved in a constant interaction with his environment and with the aim of adapting himself as well as possible to that environment in order to upkeep his own biological system (Chisholm [25], cited by Mouwen [26]). Using his cognitive capacities a person can make an internal representation of reality. This is done by picturing what things are like and transforming these impressions in some narrated form that makes sense. This internal representation, that also comprises the self-image, functions as an interface between oneself and the world. The internal representation must be kept up-to-date to enable the person to act adequately, predict what is coming upon his/her path and attune his/her response to it (Holland [27], cited by Mouwen [26]). It is a continuous process of attuning and testing. How a person sees one’s self as a unique individual is also subject to this testing and attuning and is experienced as the question we ask ourselves about the meaning of our lives. The attuning and testing of the internal representation is usually embedded in daily activities. Curiosity, exploration, play and imagination function as urges for a person to look actively for optimal conditions for maintaining one’s self as an organism on a highly complex level. Emotions play an important role in guiding this process of adaptation. Emotions cause a feeling of urgency that helps someone to focus his attention on important choices, as has also been confirmed in neurobiological research [28]. This process is part of the engagement with others and the involvement in the world (someone’s environment). It is very much interactional and experiential. In other words: it is linked up with doing and acting and what you feel and experience as a consequence (‘enactment’). The self-image it contributes to, does not reside somewhere ‘between the ears’ but at the extremities of the nerves where these have an open contact with the world outside oneself. In recent studies into consciousness and emotions ‘enaction’ has been recognized as an important concept: “Consciousness in any modality depends on an enactive emotional component motivating attention; eventrelated potentials further suggest that this motivationally valenced ‘looking-for’ dimension is the conscious dimension of seeing or thinking [29]”.

The above process is not a random one. We may speak of a ‘psychological niche’ in which someone has organized his orientations (cognitions) towards the world. These orientations constitute a set that can be used to select information from the environment as taking in total reality would cause an overload of our nervous system. We can see these blocks of information as environmental variables for someone to respond to and play upon with action. The neuro-cognitivists label these variables as ‘affordances’: available potentials. Humans are complex, selfregulative organisms that monitor whether internal or external conditions (read ‘affordances’) can be manipulated in order to realize a certain pattern of action. Action patterns must preferably bring the level of functioning to a higher level of energy exchange [29]. Emotions have a role in prioritizing which action pattern must be activated. The stories that accompany these action patterns are the internal and, when told to others, the external representation that go with them.

Nurses Facilitating the Development of Recovery Narrative

We combine now how people experience their lives with the dynamics of adaptation and attunement that are at work in the constant updating of the internal representation. Achieving a higher level of energy exchange in a biological evolutionary sense has a pendant in the need for a story about oneself and one’s relationship with the world that represents one’s intentions, goals and values in a credible way. The constructing and developing of a meaningful story may be crucial to the transformation of someone’s illness identity and the incorporation of themes of empowerment and agency [30]. This ‘narrative enhancement’ finds its roots in the narrative tradition of psychotherapy [31]. and trauma therapy [48]. Professionals can help service users to cope with their emotions and understand them as elements of a personal story.

They need empathic resonance to do so, but they can also support the process of making sense of their experiences and recovery by facilitating story-making, for instance with the Wellness Recovery Action Plan [32] and other peer-led groups (for more information consult: www.ementhe.eu). This was also confirmed in the findings of the REFOCUS programme that aimed to develop a recovery orientation in adult mental health services [33]. The components of the REFOCUS intervention that resulted from an extensive literature study comprised the following: understanding values and treatment preferences; assessing strengths; and supporting goal-striving. Using a tool box of consultation techniques, assessing strengths for instance is what the Strengths-approach by Rapp & Goscha [34] aims at. However, the technical-rational character of making inventories of strengths in order to assist service users in planning recovery targets does not appeal to everyone. It may remind service users too much of treatment talk and therapy. It also runs the risk of ending up in too much rational talking and planning what to do (goal orientation) and in this way ignoring a deeper felt core of spiritual meaning.

Humans however have a capacity of experiencing a connection with other people, nature, the cosmos or God in a more spiritual sense, transcending the more functional, psychological and social explanations as mentioned above. Spirituality concerns a person’s deep feelings and beliefs, including a person’s sense of peace, purpose, connection to others and beliefs about the meaning of life [50]. It is a broad, overarching domain that may include religiosity, but religiosity is not a necessary element of spirituality [35]. Spirituality can be distinguished from spiritual well-being that stems from a broader sense of peace and contentment with living in agreement of fundamental values. These values need not always be explicitly reflected on (but they do in the case of the more overt spirituality). Nurses can become more aware of the spiritual needs of the service user by developing and using basic strategies such as listening, and being attentive to cues and body language [35, 36]. Spirituality is fundamental to managing one’s illness [37]. It may act as social support, as a buffer against stress and facilitate coping.

Spirituality enables the individual to rise above adversity, cope with it and make sense of the current situation. Spirituality invigorates the unique psychosocial strengths of the individual so that he or she can organize and value life [35].

How can professionals combine the skills that match emotional intelligence with the pragmatics of story-telling and the more spiritual reflection on the meaning of one’s life, that is how to live a life that is redeemed as satisfactory and hopeful?

I think this can be done by narrative means along with organizing experiences that preferably are shared by the professional with the patient. Let’s first focus on narrative means.

A. Make the client’s narrative the starting point and find a common ground you (professional and client) can both relate to. Then try to develop this in a shared story line [38].

B. Challenge the client to alterate a perspective or the role he or she takes in his own story and then see how this influences the story plot.

C. Make use of metaphors to suggest visual imagery for what otherwise would need a thousand words to explain or describe [39].

D. Simply inquire after what the problem is and in this way trigger reflection on the 5 components of the narrative pentad. The Dutch professor Van OS [40] called this diagnostics of the questioning mode, which is versed in common everyday language.

1) What happened with you?

2) What is your vulnerability and what is your strength?

3) What would you like to achieve?

4) What do you need for this?

The ‘organizing of experiences that preferably are shared’ refers to the aspect of reciprocity: the professional relates to his client’s story in a personal way with examples of how it is to be vulnerable but also examples of one’s strength from one’s own private life. It also concerns our understanding that for the sake of authenticity and commitment the contact depends on new experiences that both professional and client can share as if they were companions on a discovery journey.

Secondly the professional can use unconventional tools to facilitate reflection on the meaning of one’s life. We will describe two examples: using photography and the Yucel method.

Using Photography

Start with creating an experience that proceeds from the search for sources of strengths and consider it as a journey. After all, recovery is a search and a journey of discovery [41]. What a client will discover cannot be predicted on beforehand, let alone that it can be formulated as a goal. What it takes is to engage on the journey and learn from new experiences. Take photographs on the route. Examples of an ‘experience’ may be: visit the client’s hometown; go to a football-match, picking up a dog at the dog shelter (Figure 2). The client takes direction here and the caregiver follows. His role is to create conditions. One of the conditions is to make the experience safe and not too difficult to handle. The experience must somehow be framed, delimited and concrete and palpable. Making photographs does exactly that: the image being a sample from the larger world (cropping space into the photographic cadre) and fixing a moment in the flow of time. The photographs invite reflection and together they make a story that shows where someone comes from, what journey was undertaken (activities) and where the journey led the client. This is a report with images that may function as a baken for the client and that reminds him of his journey and will stimulate further reflection on the things that are important in life [14] (Figure 2)

Figure 2: :An example of a photographic report from ‘Look at Me!

Marian and her dog: The dog helps me tremendously. I picked him out from all the others in the dog shelter. He was a great companion who contributed to my recovery: my living on my own. He helped me through difficult moments [47].

Visualization of otherwise difficult abstract or diffuse feelings and thoughts encadres and concretize the flowing enigma of life, which we usually only know by prediscursive intuition [42, 43]. We sometimes know certain things which we are not yet able to put into language, because they need to be expressed first before reflection ensues. Considered from the angle of hermeneutic phenomenology [43] it is the first step of symbolization that triggers verbalization. Not only photographs can bring out into expression these impressions that come before they are objectified through language and which we know intuitively. Also arts-based therapies are based on this principle [44, 45]. And let us not forget the potential of playing. As we saw before curiosity, exploration, play and imagination have a function in affirming and attuning a person’s internal representation. Maybe this explains the success of another method in Dutch mental health care: the Yucel method [49].

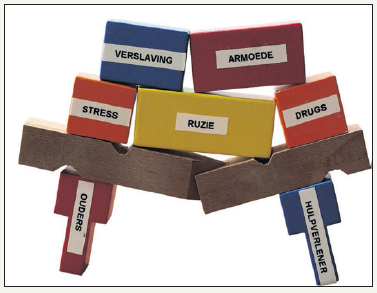

The Yucel method ‘working on recovery’ is a playful and innovative response to the demand for more self-management in health care. In future a greater appeal will be made on the patient’s own strength. In the current care system most of the time professionals use linguistic and abstract terms in their contacts with clients. As a client you are expected to adapt to the language and conceptual framework of your social worker or your community nurse. The Yucel method works differently. With colored blocks, the client builds a representation of his life’s situation (Figure 3). The client describes his problems (burdening factors) and the support that he gets from himself and others (supporting factors) in his own words and then put the blocks representing these factors as tangible entities on the table. It makes it much easier to see one’s problems and needs for support and the relation between them. The therapist helps the client to finish building this representation. He or she will stimulate the thought process by asking questions and encouraging the client. The client takes a picture of each representation afterwards. In time, the client will be able to look back on the changes that have taken place (Figure 3).

Figure 2: :working with colored blocks (the Yucel method)

The Yucel method speaks a visual language. It’s a language that focuses on simplicity and overview. For every burden, the client chooses a rectangular block. On this block her or she writes the name of the problem. For example, the client writes down: ‘fear’ or ‘alcohol’ or ‘arguments’. He/she also writes down the name of every supporting factor, i.e. ‘partner’, ‘colleague’ or ‘brother’. Naturally, each of these words stand for a wide range of emotions and affairs. But in the representation that the client will be building he only uses the summaries, the keywords of his/her burdening- and supporting factors. In this way the Yucel method helps a person to make an internal representation of reality. By recognizing the elements of the representation as building blocks for one’s course in life and then literally building it with the wooden blocks as a construction (which is a metaphor for a life story) the client pictures what things are like and that is of immense importance to help someone to transform these impressions in a narrated form. Thus the client gets an overview of his problems and his sources of support in a visual manner.

Discussion

The visual aspect in both cases (photography and the Yucel method) makes it more easy to share the narrative as a common ground. Reflection on life’s choices from deeper layers within the self-image and the perspective of how a person looks upon the world link up in a concrete and palpable/visual representation that facilitates giving and receiving feedback from (relevant) others [46]. This can be considered instrumental in creating a working alliance between the care professional and the client.

Conclusion

´Acknowledging´ (the service user as a person with his own story), ´stimulating the service user´(to tell his story) and empathic listening are important emotional interpersonal skills that are needed in recovery oriented mental health care. Beside these skills that are part of an emotional intelligence mental health nurses also need narrative competences to assist clients in finding their own story. These competences encompass the linguistic and hermeneutic forms, derived from narratology (for instance the use of metaphors) and the more contemplative reflexive formats as for instance using photo-stories and the yucel method.

References

- Stickley T, Higgins A, Sitvast J, Doyle L, Ellila H, et. al (2016) From the rhetoric to the real: A critical review of how the concepts of recovery and social inclusion may inform mental health nurse advanced level curricula - The eMenthe project. Nurse Education Today 37: 155-163.

- Anthony & William A (1993) Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16(4): 11-23.

- Van der Stel J (2012) Focus op herstel bij psychische problemen. Den Haag (The Netherlands): Boom Lemma.

- Debats DL (1996) Meaning in life: Clinical relevance and predictive power. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 35:503–516.

- Steger MF, Mann J, Michels P & Cooper T (2009) Meaning in life, anxiety, depression, and general health among smoking cessation patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 67(4): 353–358.

- Steger MF & Kashdan TB (2009) Depression and everyday social activity, intimacy, and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology 56(2): 289– 300.

- Harlow LL, Newcomb MD & Bentler PM (1986) Depression, selfderogation, substance use, and suicide ideation: Lack of purpose in life as a mediational factor. Journal of Clinical Psychology 42(1): 5–21.

- Kashdan TB, Kane JQ & Kecmanovic J (2011) Posttraumatic distress and thepresence of posttraumatic growth and meaning in life: Experiential avoidance as a moderator. Personality and Individual Differences 50(1): 84–89.

- Triplett KN, Tedeschi RG, Cann A, Calhoun LG, & Reeve CL (2012) Posttraumatic Growth, Meaning in Life, and Life Satisfaction in Response to Trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.Advance online publication 4(4): 400-410.

- Van’t Veer J (2006) The social construction of psychiatric stigma (thesis). Enschede: University of Twente, Netherland.

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE & Rusch N (2009) Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practice. World Psychiatry 8(2): 75-81.

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J & Slade M (2011) Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry 199(6): 445- 452.

- Sitvast J (2011) Living with severe mental illness: perception of sickness. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67(10): 2170-2179.

- Sitvast J (2015) Recovery in Mental Health Care with the Aid of Photostories: An Action Research Based on the Principles of Hermeneutic Photography. Nursing and Health 3(6): 139-146.

- Tan H, Wilson O & Olver I (2009) Ricoeur’s Theory of Interpretation: An Instrument for Data Interpretation in Hermenutic Phenomenology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8(4): 1-15.

- Lindseth A & Norberg A (2004) A Phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci 18(2): 145- 153.

- Maggs Rapport F (2000) Combining methodological approaches in research: ethnography and interpretive phenomenology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 31(1): 219-225.

- Barker P & Buchanan-Barker P (2005) The Tidal Model: A guide for mental health professionals. Hove and New York: Brunner-Routledge.

- Wilken JP (2010) Recovering Care. A Contribution to a theory and practice of good care. Amsterdam: SWP Publishers.

- Labov W & Waletsky J (1967) Narrative analysis. In: J. Helm (Ed), Essays on the verbal and visual arts (pp.12-44). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Schroots JJF (1996) The fractal structure of lives: Continuity and discontinuity in autobiography. In J. E. Birren, G. M. Kenyon, J.-E. Ruth, J. J. F. Schroots & T. Svensson (Eds.), Aging and biography: Explorations in adult development (pp. 117-130), New York.

- Rubin D (1996) Remembering our past: Studies in autobiographical memory. Cambridge University Press, US.

- Burke k (1945) A Grammar of Motives. Prentice-Hall, New York, USA.

- Snyder CR (2000) Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures & Applications. San Diego: Academic Press, London, UK.

- Chisholm JS (1999) Death, hope and sex: steps to an evolutionary ecology of mind and morality. Cambridge: Yale University, US.

- Mouwen AM (2004) Betekenisgeving is van levensbelang. De ervaring van zin als schakel tussen natuurwetenschap, geesteswetenschap en levensbeschouwing [Meaning giving is of vital interest. The experience of meaning as connection between science, humanities and theology]. Tijdschrift voor Humanistiek 19: 73-81.

- Holland, J. H. (1992). Complex Adaptive Systems, Daedalus. Complex Adaptive Systems 121(1): 17–30.

- Damasio AR (1999) The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace, New York.

- Ellis RD (2005) Curious Emotions. Roots of consciousness and personality in motivated action. Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Yanos PT, Roe D & Lysaker PH (2010) The Impact of Illness identity on Recovery from Severe Mental Illness. American Journal of Psychiatric. Rehabilitation 13(2): 73-93.

- White M & Epston D (1990) Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. WW Norton & Company, New York.

- Fukui S, Starnino VR, Susana M, Davidson LJ, Cook K, et al (2011) Effect of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) Participation on psychiatric symptoms, sense of hope, and recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J 34(3): 214- 222.

- Slade M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Farkas M, Grey B, et al (2015) Development of the REFOCUS Intervention to increase mental health team support for personal recovery. British Journal of Psychiatry 207(6): 544-550.

- Rapp CA & Goscha RJ (2006) The Strengths Model. Case Management with People with Psychiatric Disabilities. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Adegbola M (2006) Spirituality and Quality of Life in Chronic Illness. The Journal of Theory Construction & Testing 10(2): 42-46.

- Leeuwen van R, Tiesinga LJ, Post D & Jochemsen H (2006) Spiritual care: implications for nurses’ professional responsibility. Journal of Clinical Nursing 15(7): 875-884.

- Koenig H, Ceorge LK & Siegler IC (1988) The use of religion and other emotion-regulating coping strategies among older adults. Gerontologist 28(3): 303-310.

- Sitvast J (2017a) Importance of Patient’s Narrative and Dialogue in Healthcare. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 19(2): pp. 1, ISSN 1522-4821.

- Sitvast J (2017b) Narrative, Meaning Making and Context-Based Care: How to Realize Person-Centred Care. J Comm Pub Health Nursing, pp.3:3.

- Van Os J (2014) Persoonlijke diagnostiek in een nieuwe ggz: De DSM-5 voorbij! Leusden, Diagnosis Uitgevers, Netherland 56(5): 356-357.

- Higgins A & McBennett P (2007) The petals of recovery in a mental health context. British Journal of Nursing 16(14): 852-856.

- Cassirer E (1955) The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. Volume 1: Language. Yale University, London.

- Cassirer E (2008) Taal en Mythe (original title: Sprache und Mythos and Die Begriffsform in mythischen Denken: Gesammelte Werke, Hamburg: Meiner Verlag, 2003). Translated in Dutch by Stephan van Erp & Huub Stegeman. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Boom, Netherlands.

- Stickley T (2010) The arts, identity and belonging: A longitudinal study, Arts & Health 2(1): 23-32.

- Stickley T & Hui A (2012) Arts In-Reach: taking ‘bricks off shoulders’ in adult mental health inpatient care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 19(5): 402–409.

- Sitvast J (2017) The Aenesthecizing and Mimetic Power of Photographs: Representation of Reality in Photo-Stories. SM J Nurs 3(3): 1015.

- Bogert I, Bogert G & Sitvast J (2012) Kijk Mij Nou! Herstel in Beeld Look at me! Image recovery. Eibergen: Helios Kalenders (self publishing).

- Carey M (2009) The Absent but Implicit: a Map to Support Therapeutic Enquiry. Family Process, 48(3): 319-331.

- Yucelmethod (2018) vof The Netherlands, Europe.

- National Cancer Institute (2016) Netherlands, Europe.

- Bruner J (2001) Self-making and world-making. In: Brockmeier J & Carbaugh D, Ed & Ed, Narrative and identity. Studies in Autobiography, Self and Culture Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, Netherlands, p. 25-28.

© 2018 Jan Sitvast. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)