- Submissions

Full Text

Intervention in Obesity & Diabetes

Alexithymia in Type I and Type II Diabetes

Markus Stingl1*, Katrin Naundorf2, Lisa vom Felde1, Bernd Hanewald1

1Center for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Justus-Liebig-Universitaet Giessen

2Kerckhoff-Klinik GmbH, Psychocardiology, Benekestr. 2-8, 61231 Bad Nauheim, Germany

*Corresponding author: M Stingl, Center for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Giessen site, Klinikstr. 36, 35385 Giessen, Germany

Submission: February 09, 2018;Published: April 02, 2018

ISSN 2578-0263

Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

Objective: The course of the diabetes is significantly determined by individual behavior. In addition to disease-specific knowledge, self-care and adequate responses to emotional needs seem to be vital for a sufficient glycemic control.

Method: We examined the emotional impairments in 121 type I and type II diabetics by measuring their extent of alexithymic characteristics via the Toronto-Alexithymia-Scale (TAS-26).

Results: Both diabetic patients (type I and type II) showed significant more difficulties in identifying and verbalizing emotions than the norm sample, but a lower external-oriented thinking style. In this context, we found no differences between type I and type II diabetics. The implications of these findings for the diabetes care are discussed.

Introduction

In addition to organic reasons, psychological factors seem to play a crucial role in causing and amplifying diabetes. Several studies found a substantial correlation of psychosocial factors with diabetes, e.g. critical life events with diabetes type I [1] posttraumatic stress disorder [2] or depression in type II diabetes [3,4]. Furthermore, receiving the diagnosis of diabetes itself can be a critical life event with dramatic character and cause psychological disturbances or adjustment disorders [5]. Subsequently, rejecting and denying the diabetes disease can worsen medical compliance. Failure to keep a diet, not taking medication or omitting the insulin substitution can lead to a metabolic imbalance and increase the risk for complications later on [6,7]. These physical negative long-term consequences can reduce a person´s quality of life and mental health by inducing or maintaining depression or fear [8,9]. Especially abnormally high fear of hypoglycaemia is prominent in diabetic patients, who by constantly trying to avoid possible hypoglycaemic states suffer the consequences of excessive elevated blood sugar values. These patients also often mistake the physical symptoms of fear with symptoms of hypoglycaemia [10,11].

The treatment of diabetes mellitus requires high patient compliance. Crucial for the long-term outcome is the fact that poorly controlled diabetes initially causes only a few complaints but manifests clinically with a latency of several years or even decades. These late effects such as micro- and macroangiopathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy or diabetic foot are then often severe and irreversible. Mental illnesses can affect compliance and the ability to adequately anticipate long-term consequences [12]. The impact of psychological factors becomes particularly clear with the phenomenon of “Brittle diabetes”, which is characterized by an instable insulin-dependent diabetes with frequently changing states of hyper- or hypoglycaemia without sufficient medical explanations for these fluctuations. Several psychotherapeutic studies showed that unconscious conflicts impair the affect regulation, and as a result the blood glucose regulation of patients with brittle diabetes [12-14]. These psychological findings are in line with psychophysiological approaches, which explain the impact of psychic self-regulation on the blood glucose regulation through stress hormones like cortisol or catecholamines, which energize the organism and therefore increase the blood glucose level [15].

From a clinical point of view to face emotional difficulties in patients, the construct of alexithymia (a=non, lexis=reading, thymos=feeling) describes an emotional impairment in identifying and verbalizing feelings and an accompanying externally oriented, fact-based way of thinking [16,17]. Alexithymia is considered to be a factor enhancing the vulnerability to different physiological and psychological illnesses [18]. For instance, different studies have shown increased prevalence rates of high alexithymic characteristics in persons with eating disorders [19,20], depression [21], hypertension [22], ulcerating colitis / Crohn´s disease [23], asthma [24] and rheumatoid arthritis [25].

However, research focussing on alexithymia in diabetes yielded different results so far. While Damak et al. [26] found no increased alexithymic features in type II diabetics, Friedmann et al. [27] reported slightly higher alexithymia charateristics in insulin- dependent diabetics of both types. A study by Manfrini et al. [28] showed increased alexithymia in nearly half of the examined type I diabetics and Sapozhinkowa et al. [29] found a similar prevalence for alexithymia in type II diabetics. An examination of patients suffering from a metabolic syndrome found increased alexithymic characteristics and identified alexithymia as an aggravating factor for the exacerbation of metabolic symptoms [30]. High alexithymic characteristics were also found in diabetes patients with terminal renal failure and bulimia [31]. Regarding blood glucose measurement and management, Housiaux et al. [32] found an association with alexithymia in type I diabetic children. Also, Luminet et al. [33] observed a predictive correlation of alexithymia and blood glucose self-measurement within an 8-week trial.

Based on these findings going beyond physiological aspects causing diabetes, we focussed on emotional differentiation impairments in diabetic patients. As studies up-to-date examined only alexithymia in one type of diabetes, the aim of our study was to contrast and differentiate possible emotional limitations between type I and type II diabetics by measuring their degrees of alexithymia.

Method

We surveyed 121 patients, comprising type I (N=44; 36.4%) and type II (N=77; 63.6%) diabetics who participated in a diabetes training program by administering the Toronto-Alexithymia- Scale-26 (TAS-26). The TAS-26 is a self-rating instrument to assess the alexithymic core characteristics on three subscales: “difficulties in identifying feelings”, “difficulties in verbalizing feelings”, and an “externally-oriented thinking style” [34]. The survey comprises 26 items with 5-step rating scales and is a validated adaption of the international recognized Toronto-Alexithymia-Scale-20 [35] Cronbach´s alpha: 0.67-0.84). For the statistical comparisons we contrasted the sample mean values with the norm sample via t-test (α=.005).

There was no significant gender difference between the two subgroups of type I and type II diabetics (χ2(df=2; n=121)=0,416; p=.812).

Results

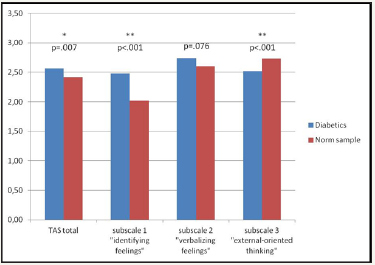

The degree of alexithymic characteristics in diabetic patients was higher compared to the normal population (Meandiff=0.15, p=0.007, T=2.76, df=112). Concerning the subscales, diabetic patients on average reported significantly more difficulties in identifying their feelings (p<0.001, T=6.17, df=112) and slightly more difficulties in finding words for their feelings (p=0.076, T=1.79, df=112). On the other hand, the patients showed a less externally—oriented thinking style than the normal population (p<0.001, T=-3.327, df=112) (Figure 1).

Contrasting the two sub groups (type I and II) of diabetic patients, we found no group differences in their global degree of alexithymia (p=0.836, T=0.207, df=79.4) nor in the subscales.

Figure 1: Comparison of Alexithymia scores (TAS-26) in diabetic patients (n=121) vs. Norm sample.

Discussion

The surveyed diabetic patients reported significantly higher alexithymia scores measured by the TAS-26 than the normal population. This is in line with findings in other chronic diseases (e.g. hypertension, ulcerating colitis, Crohn´s disease, asthma and rheumatoid arthritis), where patients also showed more pronounced alexithymic characteristics. The diabetic patients reported remarkable difficulties in identifying and verbalizing their emotions, which can impede their ability to adequately regulate emotional states, e.g. addressing their personal sensitivities in interpersonal conflicts. These emotional impairments are eminently problematic in diabetic patients because of the well known impact of emotional burden or ongoing stress on blood glucose regulation. Studies observed increased blood glucose concentrations following stressful situations [36,37] or heightened HbA1c-values in diabetics exposed to chronic stress [38,39] highlighting the importance of stress regulation techniques to cope with the accompanied increase of the physiological blood glucose level.

Furthermore, appropriate experiences of one’s bodily states are commonly embedded in an emotional context. Diabetics with high alxithymic characteristics, however, may have difficulty being aware and perceiving these sensations in order to adjust their necessary insulin dosage.

However, the observation of lower values on subscale 3 (“externally-oriented thinking”) in diabetics compared to the normal population is striking. Valera et al. [40] assume that a genetically determined alexithymia phenomenologically appears mostly on this scale, as their studies in monzygotic twins suggested. Conversely, this could mean that the observed alexithymic pattern in this study (high impairments in identifying and verbalizing feelings without an accentuated external thinking style) is acquired instead of congenital [40,41]. Following this line of reasoning, it is possible that the alexithymic features resulted from dysfunctional coping strategies, which again can have a negative impact on the course of the diabetic disease.

Having these results in mind, the question arises if the treatment and training measures for diabetic patients have to be expanded. Some case studies reported positive effects of emotion focussed psychotherapy in patients with Brittle diabetes on their self-care [13,14]. The latter is crucial for an adequate diabetes management to prevent late sequelae. By treating alexithymic patients suffering from other chronic diseases with emotion focussed elements like fostering the perception of bodily sensations and concomitant feelings, these therapy studies obtained promising results [42,43]. Additionally, because alexithymic people do not seem to have deficits in their imagination abilities, alexithymic diabetic patients could potentially benefit from relaxation or imagination techniques to learn and improve regulating their emotional states [44,45].

Usually, diabetic education programmes focus on knowledge transfer about the disease and its management on a “technical” level [46]. Our findings of impaired emotional abilities in diabetics suggest an additional focus on these impairments within the training of diabetic patients, promoting treatment concepts, e.g. the psychosocial PRO-measures [47] going beyond glycemic control in diabetic patients.

Limitations

First, despite its international widespread use, the Toronto- Alexithymia-Scale is a self-report instrument and therefore evaluates the subjective judgements of the participants requiring knowledge about their own impairments. Second, we did not control for duration of the diabetic disease nor the number and severity of comorbidities. Finally, the proportion of type I and type II diabetic patients in the study sample was higher than the proportion in the normal population. Therefore, our results need to be interpreted having these limitations in mind.

References

- Hägglöf B, Blom L, Lönnberg G, Sahlin B, Dahlquist G (1991) The Swedish childhood diabetes study: indications of severe psychological stress as a risk factor for Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes in childhood. Diabetologia 34(8): 579-583.

- Lukaschek K, Baumert J, Kruse J, Emeny RT, Lacruz ME, et al. (2013) Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and Type 2 Diabetes in a population-based cross-sectional study with 2970 participants. J Psychosom Res 74(4): 340-345.

- Yu M, Lu F, Fang L, Zhang X (2015) Depression and Risk for Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Can J Diabetes 39(4): 266-272.

- Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH (2008) Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 31(12): 2383-2390.

- Beutel M (1985) Zur Erforschung der Verarbeitung chronischer Krankheit: Konzeptionalisierung, Operationalisierung, und Adaptivität von Abwehrprozessen am Beispiel von Verleugnung. [Chronic illness: conceptualization, operationalization and adaptivity of defense mechanisms by the example of denial. Psychother Med Psychol 35: 295- 302.

- Janka HU, Balletshofer B, Becker A, Giek MR, Hartmannn J, et al. (1992) Das metabolische Syndrom als potenter kardiovaskulärer Risikofaktor für vorzeitigen Tod bei Typ-lI-Diabetikern. [The metabolic syndrom as a potent risk factor for premature death in type II diabetics] Diab Stoffw 1: 2-7.

- Petermann F, Noecker M, Bode U (1987) Psychologie chronischer Krankheiten im Kinder- und Jugendalter [Psychology of chronical illnesses in chidren and youth]. Psychologie Verlagsunion. München/ Weinheim: 1987.

- Rustad JK, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB (2011) The relationship of depression and diabetes: pathophysiological and treatment implications. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36(9): 1276-1286.

- Pirraglia PA, Gupta S (2007) The interaction of depression and diabetes: a review. Curr Diabetes Rev 3(4): 249-251.

- Delamater AM, Jacobson AM, Anderson B, Cox D, Fisher L, et al. (2001) Psychosocial therapies in diabetes: report of th Psychosocial Therapies Working group. Diabetes Care 24(7): 1286-1292.

- Turkat ID (1982) Glucosylated haemoglobin levels in anxious and nonanxious diabetic patients. Psychosomatics 23: 1056-1058.

- Isla Pera P (2012) Chronic complications of diabetes mellitus. Recommendations from the American Diabetes Association 2011. Prevention and management. American Diabetes Association. Rev Enferm 35(9): 46-52.

- Brosig B, Leweke F, Milch W (2001) Psychosoziale Prädiktoren der metabolischen Instabilität bei Brittle Diabetes [Psychosocial praedictors of metabolic instability in Brittle Diabetes]. Psychother Psych Med 51: 232-238.

- Leweke F, Kurth R, Milch W, Brosig B (2004) Integrative treatment of instable diabetes mellitus: education or psychotherapy? Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr 53: 347-358.

- Mach J, Stingl M, Milch W, Jurkat HB, Leweke F (2005) Brittle Diabestes– Therapieprobleme bei der stationären psychosomatischen Behandlung [Brittle diabetes–Problems in inward psychosomatic treatment. Psychotherapeut 50: 278-280.

- Barth E, Albuszies G, Baumgart K, Matejovic M, Wachter U, et al. (2007) Glucose metabolism and catecholamines. Crit Care Med 35(9): 508-518.

- Nemiah JC, Freyberger H, Sifneos PE (1976) Alexithymia: A view of the psychosomatic process. In: Hill OW (Ed.), Modern Trends in Psychosomatic Medicine, Butterworths, London, UK, 3: 430-439.

- Sifneos PE (1973) The prevalence of ‘alexithymic’ characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom 22 (2): 255–262.

- Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA (1997) Disorders of affect regulation. University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Torres S, Guerres MP, Lencastr L, Miller K, Vieira FM, et al. (2015) Alexithymia in anorexia nervosa: The mediating role of depression. Psychiatry Res 225(1-2): 99-107.

- Carano A, De Berardis D, Gambi F, Di Paolo C, Campanella D, et al. (2006) Alexithymia and body image in adult outpatients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 39(4): 332-340.

- Li S, Zhang B, Guo Y, Zhang J (2015) The association between alexithymia as assessed by the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 227(1): 1-9.

- Grabe HJ, Schwahn C, Barnow S, Spitzer C, John U, et al. (2010) Alexithymia, hypertension, and subclinical atherosclerosis in the general population. J Psychosom Res 68(2): 139-147.

- Porcelli P, Leoci C, Guerra V, Taylor GJ, Bagby M (1996) A Longitudinal Study of Alexithymia and Psychological Distress in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Psychosom Res 41(6): 569-573.

- Vazquez I, Sández E, González-Freire B, Romero-Frais E, Blanco-Aparicio M, et al. (2010) The role of alexithymia in quality of life and health care use in asthma. J Asthma 47(7): 797-804.

- Vadacca M, Bruni R, Terminio N, Sambataro G, Margiotta D, et al. (2014) Alexithymia, mood states and pain experience in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 33(10): 1443- 1450.

- Damak R, Mnif L, Masmoudi J, Halwani N, Mnif F, et al. (2010) Alexithymia in diabetes type2. European Psychiatry 25(1): 1008.

- Friedman S, Vila G, Even C, Timsit J, Boitard C, et al. (2003) Alexithymia in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is related to depression and not to somatic variables or compliance J Psychosom Res 55(3): 285-287.

- Manfrini S, Bruni R, Terminio N (2005) Alexithymia in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 48(1): 323–324.

- Sapozhnikova IE, Tarlovskaia EI, Madianov IV, Vedenskaia TP (2012) [The degree of alexithymia in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and its association with medical and demographic parameters]. Ter Arkh 84(10): 23-27.

- Lemche AV, Chaban OS, Lemche E (2014) Alexithymia as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus in the metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res 215(2): 438-443.

- Fukunishi I (1997) Alexithymic characteristics of bulimia nervosa in diabetes mellitus with end-stage renal disease. Psychol Rep 81(2): 627– 633.

- Housiaux M, Luminet O, Van Broeck N, Dorchy H (2010) Alexithymia is associated with glycaemic control of children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab 36(6 Pt 1): 455-462.

- Luminet O, de Timary P, Buysschaert M, Luts A (2006) The role of alexithymia factors in glucose control of persons with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetes Metab 32(5 Pt 1): 417-424.

- Kupfer J, Brosig B, Brähler E (2001) Toronto-Alexithymie-Skala-26. Deutsche Version. Göttingen, Bern, Hogrefe Verlag.

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ (1994) The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale--I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res 38(1): 33-40.

- Wiesli P, Schmid C, Kerwer O, Nigg-Koch C, Klaghofer R, et al. Acute psychological stress affects glucose concentrations in patients with type 1 diabetes following food intake but not in the fasting state. Diabetes Care 28(8): 1910-1915.

- McLesky CH, Lewis SB, Woodruff RE (1978) Glucagon levels during anaesthesia and surgery in normal and diabetic patients. Diabetes 27: 492.

- Stenström U, Wikby A, Hörnqvist JO, Andersson PO (1995) Recent life events, gender differences, and the control of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A 2-year follow-up study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 17(6): 433-439.

- Lloyd CE, Dyer PH, Lancashire RJ, Harris TH, Danie JE, et al. (1999) Association between stress and glycemic control in adults with type 1 (insulin dependent) diabetes. Diabetes Care 22: 1278-1283.

- Valera EM, Berenbaum H (2001) A twin study of alexithymia. Psychother Psychosom 70(5): 239-246.

- Freyberger H (1977) Supportive psychotherapeutic techniques in primary and secondary alexithymia. Psychother Psychosom 28(1-4): 337-342.

- Beresnevaite M (2000) Exploring the benefits of group psychotherapy in reducing alexithymia in coronary heart disease patients: A preliminary study. Psychother Psychosom 69(3): 117-122.

- Rufer M, Albrecht R, Zaum J, Schnyder U, Mueller-Pfeiffer C, et al. (2010) Impact of alexithymia on treatment outcome: a naturalistic study of short-term cognitive-behavioral mgroup therapy for panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom 43(3): 170-179.

- Bausch S, Stingl M, Hartmann LC, Leibing E, Leichsenring F, et al. (2011) Alexithymia and script-driven emotional imagery in healthy female subject: no support for deficiencies in imagination. Scand J Psychol 52(2): 179-184.

- Friedlander L, Lumley MA, Farchione T, Doyal G (1997) Testing the alexithymia hypothesis: physiological and subjective responses during relaxation and stress. J Nerv Ment Dis 185(4): 233-239.

- Corathers SD, Mara CA, Chundi PK, Kichler JC (2017) Psychosocial Patient-Reported Outcomes in Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes: a Review and Case Example. Curr Diab Rep 17(7): 45.

© 2018 Rishi Pal. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)